Biology:Island tameness

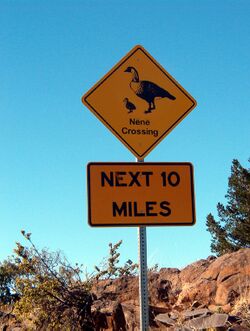

Island tameness is the tendency of many populations and species of animals living on isolated islands to lose their wariness of potential predators, particularly of large animals. The term is partly synonymous with ecological naïveté, which also has a wider meaning referring to the loss of defensive behaviors and adaptations needed to deal with these "new" predators. Species retain such wariness of predators that exist in their environment; for example, a Hawaiian goose retains its wariness of hawks (due to its main predator being the Hawaiian hawk), but does not exhibit such behaviors with mammals or other predators not found on the Hawaiian Islands. The most famous example is the dodo, which owed its extinction in large part to a lack of fear of humans, and many species of penguin (which, although wary of sea predators, have no real land predators and therefore are very bold and curious towards humans).

A comparison of 66 species of lizards found that flight initiation distance (how close a lizard allows a human "predator" to approach before it flees) decreases as distance from the mainland increases and is shorter in island than in mainland populations.[1] According to the author Charles Darwin, he believed that escape behavior evolved to be lower where predators were rare or absent on remote islands because unnecessary escape responses are costly in terms of time and energy.

Island tameness can be highly maladaptive in situations where humans have introduced predators, intentionally or accidentally, such as dogs, cats, pigs or rats, to islands where ecologically naïve fauna lives. It has also made many island species, such as the extinct dodo or the short-tailed albatross, vulnerable to human hunting. In many instances the native species are unable to learn to avoid new predators, or change their behavior to minimize their risk. This tameness is eventually lost or reduced in some species, but many island populations are too small or breed too slowly for the affected species to adapt quickly enough. When combined with other threats, such as habitat loss, this has led to the extinction of many species (such as the Laysan rail and Lyall's wren) and continues to threaten others, such as the Key deer. The only conservation techniques that can help endangered species threatened by novel introduced species are creating barriers to exclude predators or eradicating those species. New Zealand has pioneered the use of offshore islands free of introduced species to serve as wildlife refuges for ecologically naïve species.

A comparable phenomenon may be present in plant species that colonize faraway islands devoid of their natural predators on the mainland, losing anti-browsing measures (like spines and toxins). However, this point is in need of further study.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ Cooper, W. E. Jr.; Pyron, R. A.; Garland, T. Jr. (2014). "Island tameness: living on islands reduces flight initiation distance". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 281 (1777 20133019). doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.3019. PMID 24403345.

- ↑ Burns, Kevin C. (2019). Evolution in Isolation: The Search for an Island Syndrome in Plants. Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Quammen, David (2004). The Song of the Dodo: Island Biogeography in an Age of Extinctions. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-82712-4. https://archive.org/details/songofdodoisland00quam.

- Blazquez M. C., Rodriguez-Estrella R., Delibes M (1997) "Escape behavior and predation risk of mainland and island spiny-tailed iguanas (Ctenosaura hemilopha)" Ethology 103 (#12): 990-998

- Rodda, G. H.; Fritts, T. H.; Campbell, E. W. III; Dean-Bradley, K.; Perry, G.; Qualls, C. P. (2002). "Practical concerns with the eradication of island snakes". in Veitch, C. H.; Clout, M. N.. pp. 260–265. http://interface.creative.auckland.ac.nz/database/species/reference_files/TurTid/Rodda.pdf. Retrieved 2013-05-14.

- Delibes, M. & Blázquez, M.C. (1998) "Tameness of Insular Lizards and Loss of Biological Diversity" Conservation Biology 12 (#5) 1142-1143

- Bunin, J. & Jamieson, I. (1995) "New Approaches Toward a Better Understanding of the Decline of Takahe (Porphyrio mantelli) in New Zealand" Conservation Biology 9 (#1):100-106

|