Biology:Liriomyza trifolii

| Liriomyza trifolii | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Family: | Agromyzidae |

| Genus: | Liriomyza |

| Species: | L. trifolii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Liriomyza trifolii (Burgess, 1880)

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Liriomyza trifolii, known generally as the American serpentine leafminer or celery leafminer, is a species of leaf miner fly in the family Agromyzidae.

L. trifolii is a damaging pest, as it consumes and destroys produce and other plant products. It commonly infests greenhouses and is one of the three most-damaging leaf miners in existence today. It is found in several countries around the globe as an invasive species, but is native to the Caribbean and the Southeastern United States.[1][2][3][4]

Description

L. trifolii are relatively small flies for their family. The adults typically measure less than 2 mm in length. They are mostly yellow in color, although parts of the abdomen and thorax are dark brown or grey. They typically have yellow legs. A key distinction between L. trifolii and their very similar relatives, L. sativae, are L. trifolii's dark, matte mesonotum.[4]

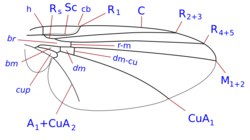

L. trifolii typically have a wingspan of 1.25 to 1.90 mm. Their wings are transparent and have veins in a similar pattern to that of flies in the Phytomyzinae subfamily.[4]

Distribution

Originally, L. trifolii was solely found in Caribbean countries and the southeastern United States (specifically concentrated in southern Florida).[4] However, export of produce and other vegetative goods from these areas has led to the dispersion of L. trifolii to several countries in Asia along the Pacific Ocean, as well as Europe, California , and certain parts of Canada . This human-facilitated dispersion occurred mostly after L. trifolii became resistant to certain insecticides and therefore were not killed off by the exports' treatment with insecticides before and after transport.[5]

Habitat

L. trifolii are naturally found in tropical and subtropical regions. However, they frequently infest greenhouses and can now be found as an invasive species in a wider variety of climates.[4] Because of this human-facilitated dispersion, L. trifolii can now be found in more temperate climates than they naturally would, although their development and survival is not as successful in the cooler climates.[4][6]

Life History

Compared to other flies, L. trifolii have a relatively brief life cycle, ranging from 21 to 28 days in habitats they are native to. Because of this, there can be multiple generations of L. trifolii within one year in warm climates.[4] Additionally, the rate of development for L. trifolii has been shown to be temperature-dependent. Maximum pupal survival rates and oviposition rates were shown to occur at 30˚C.[6]

Eggs

The eggs are typically about 1 mm long, 0.2 mm wide, and oval in shape. Initially after oviposition, the eggs are clear, but they become creamy white in color as time goes on. Eggs are laid just below the surface of the leaf; when the larvae hatch, they mine their way out of the leaf as they feed, hence the name "leaf miner". The eggs frequently fall victim to parasitoid wasps.[4]

Larval Instars

The larvae of L. trifolii are unique from those of many other flies in their shape, as the body of L. trifolii larva does not taper at the head end. The larvae are uniform in thickness at both their anterior and posterior ends but additionally have a pair of spiracles at the posterior end. They do not have legs and are initially clear in color, but gradually become yellow as they mature.[4]

The larval instars are differentiable by the lengths of the body and mouthparts. The first instar is recognizable by a mean body length of 0.39 mm and a mouthpart length of 0.10 mm. For the second instar, the mean measurements are 1.00 mm (body) and 0.17 mm (mouth). For the third instar, the mean measurements are 1.99 mm (body) and 0.25 mm (mouth). The fourth instar is a non-feeding stage and thus is usually disregarded.[4]

Pupa

Typically, at the end of the larval phase, L. trifolii drop to the soil to pupate after exiting the leaf mines they have created. Initially, the puparium is yellow, but it grows to become a darker brown over time. The puparium is typically less than 2.3 mm long and 0.75 mm wide.[4]

Adults

Adult female L. trifolii tend to live around 13 to 18 days. Male adults typically only live 2 to 3 days because they are unable to puncture plants and thus have difficulty feeding. As previously described, both males and females are typically around 2 mm in length with a wingspan around 1.25 mm.[4] After chewing a fan shape into the leaf of their host plant, adults feed on exuding sap of the host plant on which oviposition will occur.[7]

Food Resources

Both larval and adult female L. trifolii feed primarily on the leaves of their host plants. Larvae feed mostly on the layer of the leaf just below the epidermis, while female adults feed on liquids expelled by the leaves after the adult has punctured them.[4][7] L. trifolii feed on a large variety of host plants, including both vegetables and ornamental plants. Studies on the flies' preferred hosts show that some of L. trifolii's most preferable hosts are chrysanthemums, Gerber daisies, and celery. When the females are placed on preferable hosts, they produce more holes and show an increased rate of oviposition.[7]

Mating

The ways in which L. trifolii signal readiness for mating are not entirely known. Researchers have not reported the presence of any sex pheromones, but L. trifolii may attract mates and signal readiness through a series of short-distance vocalization by the males. This vocalization also manifests into male L. trifolii rapidly "bobbing" up and down when nearby to females they would like to mate with.[8]

Males are typically not overly aggressive, but aggression between L. trifolii males has been observed in severely overcrowded laboratory conditions. During copulation, if a rival male approaches a pair, the mating male will repeatedly flex his wings until the rival is scared away. This is likely a display of his fitness through his wing size.[8]

Parental Care

Oviposition

Oviposition occurs within 24 hours of mating, usually during daylight hours.[4][7] When oviposition is going to occur, the female punctures the host leaf in a tubular shape, feeding on the sap released from the leaf as she punctures.[9] Oviposition typically occurs at a rate of 35 to 39 eggs per day. Females often lay a total of 200 to 400 eggs in their lifetime when on ideal hosts such as celery. Both the rate of oviposition and the total fecundity decrease when located on less ideal host plants, such as tomatoes.[4][7]

Site Selection For Egg Laying

Eggs are typically oviposited on leaves toward the center of the host plant. Regardless of host plant, the female's first action is bending of the abdomen to position her ovipositor at the correct angle to the leaf. The ovipositor than contacts the leaf in a series of "rapid thrusts". The female punctures the leaf in either a fan shape or a tubular shape.[8] The eggs are inserted into the tubular punctures on the bottom surface of the host leaf, just below the epidermis. This is where the larva will create its mine upon hatching.[4][9] Oftentimes, the mother will make multiple punctures before selecting the ideal spot. Oviposition rate is significantly increased for female L. trifolii located on ideal host plants such as celery.[7][9]

Enemies

Parasites

The most significant natural threat to L. trifolii are parasitoid wasps. These wasps lay their eggs amongst the eggs of L. trifolii. When the wasps hatch, they typically devour the flies' nearby eggs, as is the defining characteristic of parasitoids. The most common parasitoids of L. trifolii are wasps from the families Braconidae, Eulophidae, and Pteromalidae. In the absence of insecticides, these parasitoids play a major role in keeping the L. trifolii population under control.[4]

Predators

Although predators and diseases tend to impact the L. trifolii population to an insignificant amount compared to parasitoids, both larvae and adult L. trifolii can still be at risk of predation by general predators. The most common predators of L. trifolii are ants.[4]

Interactions With Humans

L. trifolii is a highly destructive pest of both produce and ornamental plants. They often infest greenhouses and inhabit shipping containers, making them an invasive species in several countries around the globe. Because of this, they are a quarantine species in several countries, meaning their host plants are isolated for testing when L. trifolii are found on them.[5][10] L. trifolii are most destructive to floricultural crops, which are severely impacted by any insect damage. Leaf miner abundance is assessed using a variety of sampling methods, including counting mines, counting live larvae, collecting pupae, and capturing adults.[4] L. trifolii can be destructive to crops in many ways, including spreading diseases, destroying seedlings, and altering leaf production, which damages the fruits. All of these impacts on the crops decrease their value, which can be catastrophic to the industry.[8]

Insecticide Resistance

The spread of this pest is widely due to the fly's developed resistance to certain insecticides. This has been a major issue combatted by attempts from the Florida Fruit and Vegetable Association (FFVA) to mitigate the infestation and spread of these pests. However, due to previous spreading of L. trifolii through exported goods, L. trifolii are already a major pest of ornamentals in California.[10][11] The California chrysanthemum industry lost approximately $93 million to damage caused by L. trifolii in the 1980s.[8] Insecticides also kill off parasitoids that inhabit the area. Thus, the use of insecticides not only damages the ecosystem, but also reduces the population of the main form of biological control for L. trifolii.[4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Liriomyza trifolii Report". https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=144045.

- ↑ "Liriomyza trifolii". https://www.gbif.org/species/1553384.

- ↑ "Liriomyza trifolii species Information". https://bugguide.net/node/view/856171.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 "American serpentine leafminer - Liriomyza trifolii (Burgess)". http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/veg/leaf/a_serpentine_leafminer.htm.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Minkenberg, O. P. J. M. (1988). "Dispersal of Liriomyza trifolii" (in en). EPPO Bulletin 18 (1): 173–182. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2338.1988.tb00362.x. ISSN 1365-2338.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Leibee, G. L. (1984-04-01). "Influence of Temperature on Development and Fecundity of Liriomyza trifolii (Burgess) (Diptera: Agromyzidae) on Celery" (in en). Environmental Entomology 13 (2): 497–501. doi:10.1093/ee/13.2.497. ISSN 0046-225X. https://academic.oup.com/ee/article/13/2/497/2393359.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Parrella, M. P.; Robb, K. L.; Bethke, J. (1983-01-15). "Influence of Selected Host Plants on the Biology of Liriomyza trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae)" (in en). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 76 (1): 112–115. doi:10.1093/aesa/76.1.112. ISSN 0013-8746. https://academic.oup.com/aesa/article/76/1/112/74713.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Parrella, M P (1987). "Biology of Liriomyza". Annual Review of Entomology 32 (1): 201–224. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.32.010187.001221.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Bethke, J. A.; Parrella, M. P. (1985). "Leaf puncturing, feeding and oviposition behavior of Liriomyza trifolii" (in en). Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 39 (2): 149–154. doi:10.1111/j.1570-7458.1985.tb03556.x. ISSN 1570-7458.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ferguson, J. Scott (2004-02-01). "Development and Stability of Insecticide Resistance in the Leafminer Liriomyza trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae) to Cyromazine, Abamectin, and Spinosad" (in en). Journal of Economic Entomology 97 (1): 112–119. doi:10.1093/jee/97.1.112. ISSN 0022-0493. PMID 14998134. https://academic.oup.com/jee/article/97/1/112/2217940.

- ↑ Mason, Gail A.; Johnson, Marshall W.; Tabashnik, Bruce E. (1987-12-01). "Susceptibility of Liriomyza sativae and L. trifolii (Diptera: Agromyzidae) to Permethrin and Fenvalerate" (in en). Journal of Economic Entomology 80 (6): 1262–1266. doi:10.1093/jee/80.6.1262. ISSN 0022-0493.

Wikidata ☰ Q4285103 entry

|