Biology:Manila hemp

Manila hemp, also known as abacá, is a type of buff-colored fiber obtained from Musa textilis (a relative of edible bananas), which is likewise called Manila hemp[1] as well as abacá. It is mostly used for pulping for a range of uses, including specialty papers. It was once used mainly to make Manila rope,[2] but this is now of minor importance. Abacá is an exceptionally strong fibre, nowadays used for special papers like teabag tissue. It is also very expensive, priced several times higher than woodpulp. Manila envelopes and Manila paper take their name from this fibre.[3][4]

It is not actually hemp but is named so because hemp was long a major source of fibre, and other fibres were sometimes named after it. The name refers to the capital of the Philippines, one of the main producers of Manila hemp.[3][4] The hatmaking straw made from Manila hemp is called tagal or tagal straw.[5][6]

Diversity

The Philippines, especially the Bicol region in Luzon, has the most Manila hemp or abacá genotypes and cultivars. Genetic analysis using simple sequence repeats (SSR) markers revealed that the Philippines' abacá germplasm is genetically diverse.[7] Abaca genotypes in Luzon had higher genetic diversity than in the Visayas and Mindanao.[7] Ninety-five (95) percent was attributed to molecular variance within the population, and only 5% of the molecular variance to variation among populations.[7] Genetic analysis by Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) revealed several clusters irrespective of geographical origin.[7]

Production process

Unlike cotton and some other natural fibres like cotton Abacá plants require no pesticides, herbicides or irrigation.[8] This allows mixed-species, organic plantations in areas which were monoculture oil palm plantations, and in deforested rainforest cut down for lumber. Growing abacá plants can reduce erosion, increase biodiversity and enrich the soil. This is accomplished by interplanting abacá with other plant species and by allowing discarded abacá leaves to decompose and return their nutrients to the soil.

Cultivation

The Abacá plants are grown in Catanduanes in the Philippine highlands without the use of water or pesticides. The banana plant is harvested up to three times per year.

1. Abacá plants have several stalks which can be harvested annually and regenerate fully within a year.[9]

2. Abacá plants are harvested by “topping”, cutting the leaves with a bamboo sickle, cutting or “tumbling” the stalks. The leaves are compost on the ground, creating a fertiliser.

8. There they are sorted by colour grades, with lighter coloured fibres being more expensive due to their rarity.[10]

Processing

1. The raw fibres are tied with rope and shipped to a factory, where they are boiled and pressed into cardboard like sheets.[11]

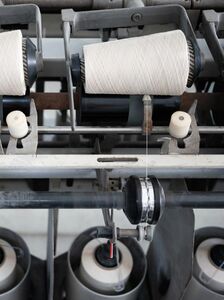

Dyeing and weaving

1. The natural white yarn is then coloured using the yarn dyeing method which is more sustainable than the roll dyeing alternative.[12]

4. The finished Bananatex brand Manila hemp fabric, a natural beeswax coating is added to make the fabric waterproof.

See also

- International Year of Natural Fibres

References

- ↑ {{citation | mode = cs1 | title = Musa textilis | work = Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN) | url = https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxonomydetail.aspx?24742 | publisher = [[Organization:Agricultural Research ServAgricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) | access-date = 5 June 2014 }}

- ↑ "Manila hemp". Transport Information Service, Gesamtverband der Deutschen Versicherungswirtschaft e.V.. http://www.tis-gdv.de/tis_e/ware/fasern/manila/manila.htm.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 H. T. Edwards; B. E. Brewer; George E. Nesom; Otis Warren Barrett; William Scrugham Lyon; Murad M. Saleeby (1904). "Abacá (manila hemp)". Farmers' Bulletin (Bureau of Agriculture. Republic of the Philippines).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Katrien Hendrickx (1904). "The Origins of Banana-fibre Cloth in the Ryukyus, Japan". Farmers' Bulletin. Studia anthropologica (Leuven University Press) 11: 170. ISBN 978-90-5867-614-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=ULyu8dNqS1sC.

- ↑ Dreher, Denise (1981). From the neck up : an illustrated guide to hatmaking (1st ed.). Minneapolis, Minn.: Madhatter. ISBN 9780941082006. https://books.google.com/books?id=fc9x1E8J0wwC&q=Tagal.

- ↑ Ginsburg, Madeleine (1990). The hat: trends and traditions (1st U.S. ed.). Hauppauge, N.Y.: Barron's. ISBN 9780812061987. https://archive.org/details/hattrendstraditi00gins. "Tagal."

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Yllano, O. B., Diaz, M. G. Q., Lalusin, A. G., Laurena, A. C., & Tecson-Mendoza, E. M. (2020). "Genetic Analyses of Abaca (Musa textilis Née) Germplasm from its Primary Center of Origin, the Philippines, Using Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) Markers – The Philippine Agricultural Scientist" (in en-US). https://pas.cafs.uplb.edu.ph/download/genetic-analyses-of-abaca-musa-textilis-nee-germplasm-from-its-primary-center-of-origin-the-philippines-using-simple-sequence-repeat-ssr-markers/.

- ↑ Rabl, 02 05 2019 um 09:54 von Sissy (2019-05-02). "Bananatex und Ochsenblut: Die Innovationen der Textilindustrie" (in de). https://www.diepresse.com/5617890/bananatex-und-ochsenblut-die-innovationen-der-textilindustrie.

- ↑ "BANANATEX®". https://www.bananatex.info/responsibility_EN.html.

- ↑ "Bananatex®, the World’s First Waterproof Fabric Made From Banana Plants" (in en-US). 2020-04-27. https://globalshakers.com/bananatex-the-worlds-first-waterproof-fabric-made-from-banana-plants/.

- ↑ "BANANATEX®". https://www.bananatex.info/index.html#manufacturing.

- ↑ "Eliminating silo thinking and the word 'waste', plus a tip from Jimi Hendrix". https://www.innovationintextiles.com/interviews/.

External links

- Abaca Plant (Musa textilis) - Manila Hemp

"Manila, or Manila Hemp, the fibre of musa textilis". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

"Manila, or Manila Hemp, the fibre of musa textilis". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.