Biology:Medial forebrain bundle

| Medial forebrain bundle | |

|---|---|

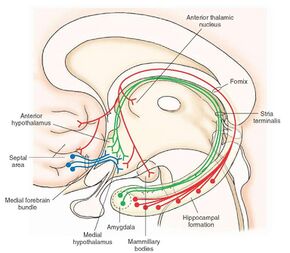

Anatomical diagram of medial forebrain bundle. These neural fibres connect the septal area in forebrain with medial hypothalamus. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | fasciculus medialis telencephali |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

The medial forebrain bundle (MFB) is a neural pathway containing fibers from the basal olfactory regions, the periamygdaloid region and the septal nuclei, as well as fibers from brainstem regions, including the ventral tegmental area and nigrostriatal pathway.

Anatomy

The MFB passes through the lateral hypothalamus and the basal forebrain in a rostral-caudal direction. The MFB has its main projections to these regions of Brodmann areas (BA) 8, 9, 10, 11, 11m. The superior frontal region of MFB projects to BA 8, 9, 10; the rostral middle frontal projects to dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (BA 9, 10); lateral orbitofrontal of MFB shows its projections to nucleus accumbens septi (NAC) and ventral striatum as subcortical reward associated structures.[1]

It contains both ascending and descending fibers. The mesolimbic pathway, which is a collection of dopaminergic neurons that projects from the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens, is a component pathway of the MFB.[2]

The MFB is one of the two major pathways connecting the limbic forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain. The other one is the dorsal diencephalic conduction (DDC) system. The two pathways seem to have parallel neural circuits, and share similar physiology and function.[3]

Function

It is commonly accepted that the MFB is a part of the reward system, involved in the integration of reward and pleasure.[4] Electrical stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle is believed to cause sensations of pleasure. This hypothesis is based upon intracranial self-stimulation (ICSS) studies. Animals will work for MFB ICSS, and humans report that MFB ICSS is intensely pleasurable.[5]

Another research technique that was used in determining the function of the MFB was microdialysis.[6] Reinforcing electrical stimulation of the MFB using this method has shown to cause a release in dopamine in the nucleus accumbens. Other microdialysis studies have shown that the presence of natural reinforcers such as food, water, and a sex partner cause a release in dopamine in the nucleus accumbens. This shows that the electrical stimulation of the MFB causes a similar effect compared to natural reinforcers.

The medial forebrain bundle has been shown to be linked to an individual's grief/sadness system through regulation of the individual's seeking/pleasure system.[7]

Potential role in diagnosis/treatment

The medial forebrain bundle may serve as a target in treating treatment-resistant depression.[8] Since the MFB connects areas of the brain which are involved with motivated behavior, mood regulation, and antidepressant response the stimulation of the MFB through deep brain stimulation could be an effective form of treatment. Subjects that receive the deep brain stimulation treatment in the medial forebrain bundle have been reported to have high remission rates with normative functioning and no adverse side effects.

The medial forebrain bundle may also serve to study abuse-related drug effects through intracranial self-stimulation.[9] ICSS targets the MFB at the level of the lateral hypothalamus and elicits a range of responses from the subject through stimulation to acquire a baseline of responses. From this baseline the subject is then exposed to varying levels of stimuli in that are high/low in amplitude and frequency. These responses are then compared to the baseline of the subject to detect for sensitivity to the stimuli. Based on the sensitivity of the response from the subject, a level of inference on the drug abuse potential can be made.

Animal research

In animal studies studying the effects of Levodopa-induced dyskinesia, a major complication in the treatment of Parkinson's disease, lesions in the medial forebrain bundle show a maximum level of severity and sensitivity to levodopa and provide insight into the mechanisms of Levodopa-induced dyskinesia.[10] Other lesions in the mouse, particularly in the striatum 6-OHDA, show a variable sensitivity to levodopa and shows the difference in lesion severity based on location.

In a study with rats, using intracranial self-stimulation implanted in the medial forebrain bundle, rats treated with nicotine and methamphetamine showed an increased speed at which they pressed a lever to induce self-stimulation.[11] The study indicates that the medial forebrain bundle may be directly linked to motivational behavior that is induced by drugs.

In a research on rats, the deep brain stimulation (DBS) on the MFB causes an increase in dopamine for 40 seconds which is above baseline but after 40 seconds, it wasn't increased above baseline.[12]

References

- ↑ "The anatomy of the human medial forebrain bundle: Ventral tegmental area connections to reward-associated subcortical and frontal lobe regions". NeuroImage. Clinical 18: 770–783. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2018.03.019. PMID 29845013.

- ↑ "Dopamine and glutamate release in the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area of rat following lateral hypothalamic self-stimulation". Neuroscience 107 (4): 629–39. 2001. doi:10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00379-7. PMID 11720786.

- ↑ "The habenular nuclei: a conserved asymmetric relay station in the vertebrate brain". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 364 (1519): 1005–20. April 2009. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0213. PMID 19064356.

- ↑ "Prolonged rewarding stimulation of the rat medial forebrain bundle: neurochemical and behavioral consequences". Behavioral Neuroscience 120 (4): 888–904. August 2006. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.120.4.888. PMID 16893295. http://content.apa.org/journals/bne/120/4/888.

- ↑ "Science-fiction turns real: Genetically engineering animals for war". 23 March 2013. http://www.salon.com/2013/03/23/science_fiction_turns_real_genetically_engineering_animals_for_war/.

- ↑ Carlson. Neil. Physiology of Behavior (11th Edition). Pearson, 2012. Online.

- ↑ "Cross-species affective functions of the medial forebrain bundle-implications for the treatment of affective pain and depression in humans". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 35 (9): 1971–81. October 2011. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.12.009. PMID 21184778.

- ↑ "The medial forebrain bundle as a deep brain stimulation target for treatment resistant depression: A review of published data". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 58: 59–70. April 2015. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.12.003. PMID 25530019.

- ↑ Negus SS, Miller LL. Intracranial self-stimulation to evaluate potential abuse of drugs. "Pharmocol Rev." 66.3 (2014):869-917. Online

- ↑ "Investigating the molecular mechanisms of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in the mouse". Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 20 Suppl 1: S20-2. January 2014. doi:10.1016/S1353-8020(13)70008-7. PMID 24262181.

- ↑ "Evaluation of motivational effects induced by intracranial self-stimulation behavior". Acta Medica Okayama 64 (5): 267–75. October 2010. doi:10.18926/AMO/40501. PMID 20975759.

- ↑ "Deep brain stimulation of the medial forebrain bundle elevates striatal dopamine concentration without affecting spontaneous or reward-induced phasic release". Neuroscience 364: 82–92. November 2017. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.09.012. PMID 28918253.

External links

|