Biology:Micropholis (amphibian)

| Micropholis Temporal range: Early Triassic

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | †Temnospondyli |

| Family: | †Micropholidae |

| Genus: | †Micropholis Huxley, 1859 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

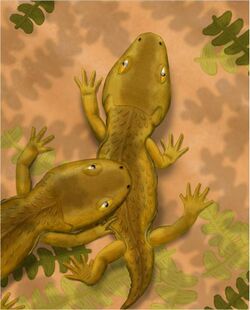

Micropholis (Greek 'mikros' = small and 'pholis' = scale) is an extinct genus of dissorophoid temnospondyl. Fossils have been found from the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone of the Karoo Basin in South Africa and are dated to the Induan (Early Triassic). Fossils have also been found from the lower Fremouw of Antarctica.[1]Micropholis is the only post-Permian dissorophoid and the only dissorophoid in what is presently the southern hemisphere and what would have been termed Gondwana during the amalgamation of Pangea.

History of study

Micropholis was one of the first dissorophoids to be named by English paleontologist Thomas Huxley in 1859 based on a partial skull.[2] Micropholis stowii (properly Micropholis stowi), the type species, is named for George William Stow, the South African geologist and ethnologist who discovered the specimen and who proposed that it represented some extinct amphibian. English paleontologist Richard Owen later named a new genus and species, Petrophryne granulata, for a better-known skull, also from the Karoo Basin, that he suggested might be the same animal as M. stowi;[3] this synonymy was eventually accepted by other workers. Additional description was furnished by German paleontologists Ferdinand Broili and Joachim Schröder in 1937.[4] The taxon was most recently revised by German paleontologist Jürgen Boy in 1985[5] and again in 2005 by German paleontologist Rainer Schoch and South African paleontologist Bruce Rubidge.[6] Micropholis has been repeatedly incorporated in phylogenetic analyses of temnospondyls and dissorophoids. In 2015, American paleontologist Julia McHugh published a description of histological patterns in Micropholis[7].

Description

Practically the entire skeleton of Micropholis is now known. Many specimens have been found, a number of which are on blocks preserving partial to complete skeletons of multiple individuals in close association,[4] and two distinct morphotypes are evident, differing in skull width and palatal dentition.[5][6]

The "slender-headed" morph is defined by corresponding narrowing of many features and cranial elements, differences in dentition on the vomer, and possibly by smaller and more numerous maxillary teeth when compared with the "broad-headed" morph. Additionally, a wide size range of individuals are known, ranging from skull lengths around 20 mm to over 40 mm. There remains some uncertainty about whether the slender-headed morph is an advanced ontogenetic stage, as the largest individuals all exhibit this skull morphology. Schoch & Milner (2014)[full citation needed] identified 10 features in the diagnosis of Micropholis:

- (1) dermal ornament, with irregularly spaced pustules;

- (2) accessory fangs on the vomer;

- (3) unpaired anterior palatal fenestra (sometimes 'fontanelle');

- (4) palatine and ectopterygoid reduces to struts along medial maxillary margin;

- (5) short basipterygoid ramus of pterygoid;

- (6) basal plate with prominent posterolateral horns;

- (7) hyobranchial skeleton well ossified;

- (8) short tail;

- (9) elongate skull table (plesiomorphy); and

- (10) postparietal much longer than tabular (plesiomorphy).

Phylogenetic relationships

When it was first described, Micropholis was recognized as a 'labyrinthodont,' an outdated term used to refer to extinct 'amphibians' in a broad sense. However, Huxley remarked that it did not show close affinities with any of the known Triassic labyrinthodonts of the time. Its uncertain affinities continued to plague paleontologists who remarked that "no types really closely allied to it have been found".[8] As a result, it was placed within its own family, Micropholidae,[9] and sometimes within its own superfamily, Micropholoidea.[10] Although it was suggested in the 1930s that Micropholis might be allied with dissorophoids by comparison with the dissorophid Broiliellus,[11] this idea was not widely adopted[10] until the 1960s.[12] Subsequent discovery of amphibamiforms, either referred to monotaxic families such as Doleserpetontidae[13] or to Dissorophidae, has further strengthened the placement of Micropholis among dissorophoids, which has since been maintained by computer-assisted phylogenetic analyses.[14] Micropholis now belongs to the recently resurrected family Micropholidae,[15] which is included in what was historically termed Amphibamidae (now Amphibamiformes). However, its placement has long been perplexing because it retains numerous plesiomorphies and is usually recovered as one of the earlier diverging amphibamiforms despite being tens of millions of years younger than all other dissorophoids.

Below is a phylogeny from Schoch (2018)[15] showing the position of Micropholis.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ Gee, Bryan M.; Sidor, Christian A. (2021-05-21). "First record of the amphibamiform Micropholis stowi from the lower Fremouw Formation (Lower Triassic) of Antarctica". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 41: e1904251. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1904251. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ↑ Huxley, T. H. (1859-01-01). "On some Amphibian and Reptilian Remains from South Africa and Australia". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society 15 (1–2): 642–658. doi:10.1144/gsl.jgs.1859.015.01-02.71. ISSN 0370-291X. https://zenodo.org/record/2179085.

- ↑ Owen, Richard (1876). "On Petrophryne granulata Ow., a labyrinthodont reptile from the Trias of South Africa, with special comparison of the skull with that of Rhinosaurus jasikovii". Bulletin Société Sciences Naturelles Moscou 50: 147–153.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Broili, Ferdinand; Schröder, Joachim (1937). "Beobachtungen an Wirbeltieren der Karrooformation. XXV. Uber Micropholis Huxley". Sitzungsberichte der Bayrischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Abteilung 1937: 19–38.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Boy, Jürgen A. (1985-01-29). "Micropholis the last surviving dissorophoid (Amphibia, Temnospondyli; Lower Triassic)" (in en). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Monatshefte 1985 (1): 29–45. doi:10.1127/njgpm/1985/1985/29. ISSN 0028-3630. http://www.schweizerbart.de/papers/njgpm/detail/1985/93439/Uber_Micropholis_den_letzten_Uberlebenden_der_Diss?af=crossref.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Schoch, Rainer R.; Rubidge, Bruce S. (2005-09-30). "The amphibamid Micropholis from the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone of South africa" (in en). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (3): 502–522. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0502:TAMFTL2.0.CO;2]. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ↑ Mchugh, Julia B. (2015-01-02). "Paleohistology of Micropholis stowi (Dissorophoidea) and Lydekkerina huxleyi (Lydekkerinidae) humeri from the Karoo Basin of South Africa, and implications for bone microstructure evolution in temnospondyl amphibians". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 35 (1): e902845. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.902845. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ↑ Watson, D.M.S. (August 1913). "II. — Micropholis stowi, Huxley, a temnospondylous amphibian from South Africa" (in en). Geological Magazine 10 (8): 340–346. doi:10.1017/S0016756800127001. ISSN 1469-5081. Bibcode: 1913GeoM...10..340W. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/geological-magazine/article/iimicropholis-stowi-huxley-a-temnospondylous-amphibian-from-south-africa/2E041B4C0EC6A60BC933C817CE362260.

- ↑ "I. The structure, evolution and origin of the amphibia. - The "orders' rachitomi and stereospondyli". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character 209 (360–371): 1–73. January 1920. doi:10.1098/rstb.1920.0001. ISSN 0264-3960.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Romer, Alfred Sherwood (1947). Review of the Labyrinthodontia. Museum of Comparative Zoology. OCLC 12898383.

- ↑ Säve-Söderbergh, G. (1935). "[Presumed Danish title not cited]". Meddelelser om Grønland [Communications on Greenland] (Copenhagen, DK) 98 (3): 1–211, plates 1–15;[full citation needed]

[reviewer not cited] (April 1935). "Reviews – Stegocephalians and primitive reptiles". Geological Magazine 72 (4): 190–191. doi:10.1017/s001675680009261x. ISSN 0016-7568. Bibcode: 1935GeoM...72..190.;

Double-citation needs to be checked: The first ref., to Meddelelser om Grønland is embedded inside the second citation, to Geological Magazine, where the first article is reviewed. It is displayed that way in the original text in the front-page of the review article in Geological Magazine. - ↑ Romer, Alfred Sherwood. Vertebrate Paleontology (Third ed.). Chicago, IL. ISBN 0-226-72488-3. OCLC 174202.

- ↑ Bolt, J.R. (1969-11-14). "Lissamphibian origins: Possible protolissamphibian from the Lower Permian of Oklahoma". Science 166 (3907): 888–891. doi:10.1126/science.166.3907.888. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17815754. Bibcode: 1969Sci...166..888B.

- ↑ Boy, Jürgen A. (1972). Die Branchiosaurier <Amphibia> des saarpfälzischen Rotliegenden <Perm, SW-Deutschland>. OCLC 163720370.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Schoch, Rainer R. (2018-11-05). "The putative lissamphibian stem-group: Phylogeny and evolution of the dissorophoid temnospondyls". Journal of Paleontology 93 (1): 137–156. doi:10.1017/jpa.2018.67. ISSN 0022-3360.

External links

- Micropholis in the Paleobiology Database

Wikidata ☰ Q6839869 entry

|