Biology:New England cottontail

| New England cottontail[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Lagomorpha |

| Family: | Leporidae |

| Genus: | Sylvilagus |

| Species: | S. transitionalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sylvilagus transitionalis (Bangs, 1895)

| |

| |

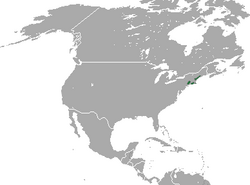

| New England cottontail range | |

The New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis), also called the gray rabbit, brush rabbit, wood hare, wood rabbit, or cooney, is a species of cottontail rabbit represented by fragmented populations in areas of New England and the state of New York, specifically from southern Maine to southern New York.[2][4][5] This species bears a close resemblance to the eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus), which has been introduced in much of the New England cottontail home range. The eastern cottontail is now more common in it.[6]

Litvaitis et al. (2006) estimated that the current area of occupancy in its historic range is 12,180 km2 (4,700 sq mi) - some 86% less than the occupied range in 1960.[2] Because of this decrease in this species' numbers and habitat, the New England cottontail is a candidate for protection under the Endangered Species Act. Cottontail hunting has been restricted in some areas where the eastern and New England cottontail species coexist in order to protect the remaining New England cottontail population.[7]

Rabbits require habitat patches of at least 12 acres to maintain a stable population. In New Hampshire, the number of suitable patches dropped from 20 to 8 in the early 2000s. The ideal habitat is 25 acres of continuous early successional habitat within a larger landscape that provides shrub wetlands and dense thickets. Federal funding has been used for habitat restoration work on state lands, including the planting of shrubs and other growth critical to the rabbit's habitat. Funding has also been made available to private landowners who are willing to create thicket-type brush habitat which doesn't have much economic value.[6]

Description

The New England cottontail is a medium-sized rabbit almost identical to the eastern cottontail.[8][9] The two species look nearly identical, and can only be reliably distinguished by genetic testing of tissue, through fecal samples (i.e., of rabbit pellets), or by an examination of the rabbits' skulls, which shows a key morphological distinction: the frontonasal skull sutures of eastern cottontail are smooth lines, while the New England cottontails' are jagged or interdigitated.[9][10] The New England cottontail also typically has black hair between and on the anterior surface of the ear, which the Eastern cottontails lacks.[8]

The New England cottontail weighs between 995 and 1347 g and is between 398 and 439 mm long, with dark brown coats with a "penciled effect" and tails with white undersides.[8] They are sexually dimorphic, with females larger than males.[8]

Distribution

New England cottontails live in New England region of the United States; habitat destruction has limited its modern range to less than 25 percent of its historic range.[8] The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) explains that:

- As recently as 1960, New England cottontails were found east of the Hudson River in New York, across all of Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts , north to southern Vermont and New Hampshire, and into southern Maine. Today, this rabbit's range has shrunk by more than 75 percent. Its numbers are so greatly diminished that it can no longer be found in Vermont and has been reduced to only five smaller populations throughout its historic range.[11]

According to at least one study, the cottontails' historic range also included a small part of southern Quebec, from which it is extirpated.[2]

The major factor in the decline of the New England cottontail population and the restriction of its range is habitat destruction from the reduced thicket habitat.[11] Before European settlement, New England cottontails were likely found along river valleys, where disturbances in the forest—such as beaver activity, ice storms, hurricanes, and wildfires—promoted thicket growth. The clearing of much of the New England forest, as well as development, has eliminated a large portion of New England cottontail habitat.[11] Other species that depend on thickets - including some birds (such as the American woodcock, eastern towhee, golden-winged warbler, blue-winged warbler, yellow-breasted chat, brown thrasher, prairie warbler and indigo bunting) and reptiles (such as the black racer, smooth green snake and wood turtle) have also declined.[12]

Various other factors also contributed to the decline of New England cottontails:

- The introduction of more than 200,000 eastern cottontails (Sylvilagus floridanus) in the early 20th century, mostly by hunting clubs, greatly harmed the New England cottontail because the eastern cottontails are a generalist species are able to survive in a wide variety of habitats (fields, farms and forest edges) and have a slightly better ability to avoid predators. The competition from the eastern cottontail led to the displacement of the New England cottontail.[11][13]

- The introduction of invasive plant species such as multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), honeysuckle bush (Lonicera maackii), and autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) in the 20th century may have also displaced many native species that the New England cottontail relied upon for food.[11]

- An increase in the population and density of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in the same range as the New England cottontail also damaged populations, because deer eat many of the same plants and damage the density of understory plants providing vital thicket habitat.[11]

In 2011, researchers from the University of Rhode Island reported that a survey found that the New England cottontail was on the verge of extirpation from Rhode Island, because of habitat loss, competition from eastern cottontails, and increased predator populations. The URI study collected nearly one thousand pellet samples from more than one hundred locations; DNA testing of the samples showed that only one contained the DNA of the New England cottontail.[13] A habitat analysis was conducted on an island in Narragansett Bay with no known past population by either cottontail species, as a possible refugium for the New England cottontail.[13]

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation also states that the New England cottontail's range in the state has been dramatically reduced because of habitat destruction and competition with the eastern cottontail.[9] Moreover, the New England cottontail and the eastern cottontail look nearly identical.[9] As a result, it is difficult to determine the New England cottontails' distribution.[9] The NYSDEC's New England Cottontail Initiative encourages rabbit hunters to submit whole heads from rabbits they have killed east of the Hudson River to the Department so they can be examined to help determine the range.[9]

According to the Nantucket Conservation Foundation, the New England cottontail occurs on Nantucket. Formerly, the species was thought to be extirpated on the island since the late 1990s, but the Nantucket Conservation Foundation and FWS believes that because the island still contained large shrubland habitat areas, there might still be a remnant New England cottontail population. In 2013, a DNA sample from a rabbit captured on Nantucket Conservation Foundation-owned Ram Pasture property in 2011 tested positive as a New England cottontail, showing that the rabbit still exists on Nantucket.[14]

Habitat

The New England cottontail is a habitat specialist.[2] It thrives in early successional forests—young forests (usually less than twenty-five years old) with a dense understory of thick, tangled vegetation (scrubland/brushland), preferably of blueberry or mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia).[2][8][11] Studies indicate that these forests matured into closed-canopy stands and the shrub layer began to thin in the 1960s, the New England cottontail habit declined.[2][11]

New England cottontails prefer woodlands with higher elevation or northern latitudes.[8] They create nests in depressions, some 12 cm (4.7 in) deep by 10 cm (3.9 in) wide, lining them with grasses and fur.[8] According to studies, New England cottontails "rarely venture more than 5 m from cover."[8]

Predation

Known predators of New England cottontails include weasels (Mustela and Neogale sp.), domestic cats (Felis catus), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), fishers (Pekania pennanti),[15] birds of prey (Falconiformes), coyotes (Canis latrans), and bobcats (Lynx rufus).[8] Past predators may have included gray wolves (Canis lupus), eastern cougars (Puma concolor), wolverines (Gulo gulo), and Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis). To avoid predators, the New England cottontails run for cover; "freeze" and rely on their cryptic coloration; or, when running, follow a zig-zag pattern to confuse the predator. Because New England cottontail habitat is small and has less vegetative cover, they must forage more often in the open, leaving them vulnerable.[8]

Reproduction and development

New England cottontails breed two to three times a year.[8] Generally, the testes of the male New England cottontails begin to enlarge in late December.[8] The breeding season varies based on local elevation and latitude, and can span from January to September. The breeding season in Connecticut lasts from mid-March to mid-September, while the breeding season in Maine lasts from April to August.[8] Pregnant female New England cottontails appear between April and August.[8] The gestation period is around twenty-eight days. Litter size ranges from three to eight, with an average of 5.2 (as given by one source)[8] or 3.5 (as given by another).[2] Generally, cottontails who live in more northern habitats have shorter gestation periods and larger litters, so they produce more litters during warmer weather.[8]

During the mating season, "male New England cottontails form breeding groups around dominant females in areas of the habitat with plentiful food and good cover."[8] New England cottontails conduct a courtship display involving running and jumping, including jumping of one rabbit over the other.[8] "Though linear hierarchies for female cottontails are not clearly defined, once paired off, the unreceptive female demonstrates dominance over the male during nesting, parturition [birth] and nursing to avoid harassment by males."[8] Generally New England cottontails will "copulate again immediately following parturition."[8]

Like all cottontails, the New England cottontail has a short lifespan, typically surviving no more than three years in the wild.[8] Moreover, an average of only 15 percent of young survive their first year.[8] New England cottontails reach sexual maturity early, at no more than one year old, and many juvenile New England cottontails will breed in their first season.[8]

Young are born naked with their eyes closed.[8] Parental investment is minimal: there is no investment by male cottontails, and female cottontails nurse their young in the nest for about 16 days, often having mated again by the time the juveniles have left the nest.[8]

Diet

New England cottontails are herbivores whose diet varies based on the season and local forage opportunities. In the spring and summer, the New England cottontails primarily eats herbaceous plants (including leaves, stems, wood, bark, flowers, fruits, and seeds) from grasses and forbs. Beginning in the fall and continuing into the winter, New England cottontails transition to mostly woody plants.[2][8]

Conservation

The New England cottontail has been listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List since 1996.[2] The species is a candidate for protection under the federal Endangered Species Act (see United States Fish and Wildlife Service list of endangered species of mammals) and is listed as endangered on state-level lists of Maine and New Hampshire.[11]

The New England cottontail is listed as "vulnerable" because of its decreasing population and reduction in suitable habitat. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service is surveying suitable habitat for this species. Due to its rarity, elusiveness, and the fact that it is nearly identical to the Eastern cottontail, DNA analysis of fecal pellets one of the best ways to identify New England cottontail populations. New England cottontails are listed as "endangered" in New Hampshire and Maine, "Extirpated" in Vermont and Quebec, "species of special concern" in New York and Connecticut, and a "species of special interest" in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Surveys are being conducted to identify areas for creating suitable habitat and to identify areas with suitable habitat that may contain remnant populations. Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and Connecticut are primary areas that may hold populations of the species. The USFWS has discovered populations in Nantucket and Eastern Connecticut. Additional surveys are being done to find more remnant populations in New England and New York.

In 2013, the State of Connecticut embarked on a habitat restoration project in Litchfield County, clearing 57 acres of mature woods to create a meadowland and second-growth forest needed by the rabbit.[16]

References

- ↑ Hoffman, R.S.; Smith, A.T. (2005). "Order Lagomorpha". in Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 211. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=13500001.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 Litvaitis, J.; Lanier, H.C. (2019). "Sylvilagus transitionalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T21212A45181534. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T21212A45181534.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/21212/45181534. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "NatureServe Explorer 2.0". https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.791204/Sylvilagus_transitionalis.

- ↑ "New England Cottontail rabbit (Sylvilagus transitionalis)". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp/species/7650.

- ↑ Marianne K. Litvaitis; John A. Litvaitis (1996). "Using Mitochondrial DNA to Inventory the Distribution of Remnant Populations of New England Cottontails". Wildlife Society Bulletin 24 (4): 725–730.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Keefe, Jennifer (April 24, 2011). "Cottontail gets help with habitat restoration". Foster's Daily Democrat. http://www.fosters.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20110424/GJNEWS_01/704249904.

- ↑ "Hunting: Small game, furbearers, other species". http://www.wildlife.state.nh.us/Hunting/Hunt_species/hunt_small_game.htm.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 8.18 8.19 8.20 8.21 8.22 8.23 8.24 8.25 8.26 Berenson, Tessa. "Sylvilagus transitionalis (New England cottontail)". University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Sylvilagus_transitionalis/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 "New England Cottontail Survey". http://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/67017.html.

- ↑ Elbroch, Mark (2006). Animal Skulls: A Guide to North American Species. Stackpole Books. pp. 247. ISBN 0811733092.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 "New England Cottontail". 2011. https://www.fws.gov/species/new-england-cottontail-sylvilagus-transitionalis.

- ↑ New England Cottontail, Rabbit at risk - Frequently asked questions, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "URI, DEM researchers: New England cottontail on verge of disappearing from Rhode Island". University of Rhode Island. September 14, 2011. https://www.uri.edu/news/2011/09/uri-dem-researchers-new-england-cottontail-on-verge-of-disappearing-from-rhode-island/.

- ↑ Beattie, Karen C. (November 22, 2013). "Update: New England Cottontails Documented on Nantucket!". Nantucket Conservation Foundation. https://www.nantucketconservation.org/update-new-england-cottontails-documented-on-nantucket/.

- ↑ "Breeding and Lifespan". Saving the New England Cottontail. https://newenglandcottontail.org/natural-history/breeding-lifespan.

- ↑ Wood, Wiley. "It's Only Natural". http://www.nornow.org/2013/06/02/its-only-natural/.

External links

- Red List detailed distribution map

- Massachusetts Cottontail Research surveys

- Website of the New England Cottontail Conservation Initiative - habitat projects

Wikidata ☰ Q404566 entry

|