Biology:Stitchbird

| Stitchbird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male in typical 'tail cocked' stance | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination

| |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Notiomystidae Driskell et al., 2007 |

| Genus: | Notiomystis Richmond, 1908 |

| Species: | N. cincta

|

| Binomial name | |

| Notiomystis cincta (Du Bus, 1839)

| |

| |

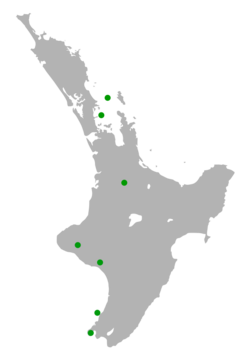

Islands and sanctuaries where stitchbirds are present

| |

The stitchbird or hihi (Notiomystis cincta) is a honeyeater-like bird endemic to the North Island and adjacent offshore islands of New Zealand. Its evolutionary relationships have long puzzled ornithologists, but it is now classed as the only member of its own family, the Notiomystidae. It is rare, being extirpated everywhere except Little Barrier Island, but has been reintroduced to two other island sanctuaries and four locations on the North Island mainland.[2] Current population estimations for mature individuals in the wild are 2,500–3,400.[3]

In addition to hihi, the stitchbird is also known by a number of other Māori names, including: tihi, ihi, tihe, kotihe, tiora, tiheora, tioro, kotihe-wera (male only), hihi-paka (male only), hihi-matakiore (female only), mata-kiore (female only), tihe-kiore (female only).[4]

Taxonomy and systematics

The stitchbird was originally described as a member of the primarily Australian and New Guinean honeyeater family Meliphagidae. It had remained classified as such until recently. Genetic analysis shows that it is not closely related to the honeyeaters and their allies and that its closest living relatives are within the endemic New Zealand Callaeidae.[5][6][7] In 2007 a new passerine family was erected to contain the stitchbird, the Notiomystidae.[6][8]

Description

The stitchbird is a small honeyeater-like bird. Males have a dark velvety cap and short white ear-tufts, which can be raised somewhat away from the head. A yellow band across the chest separates the black head from the rest of the body, which is grey. Females and juveniles are duller than males, lacking the black head and yellow chest band. The bill is rather thin and somewhat curved, and the tongue is long with a brush at the end for collecting nectar. Thin whiskers project out and slightly forward from the base of the bill.

Stitchbirds are very active and call frequently. Their most common call, a tzit tzit sound, is believed to be the source of their common name, as Buller noted that it "has a fanciful resemblance to the word stitch".[9] They also have a high-pitched whistle and an alarm call which is a nasal pek like a bellbird. Males give a piercing three-note whistle (often heard in spring) and a variety of other calls not given by the female.

Behavior and ecology

Research has suggested that they face interspecific competition from the tūī and New Zealand bellbird, and will feed from lower-quality food sources when these species are present. The stitchbird rarely lands on the ground and seldom visits flowers on the large canopy trees favoured by the tūī and bellbird (this may simply be because of the competition from the more aggressive, larger birds).

Their main food is nectar, but the stitchbird's diet covers over twenty species of native flowers and thirty species of fruit and many species of introduced plants. Important natural nectar sources are haekaro, matata, pūriri, rata and toropapa. Preferred fruits include Coprosma species, five finger, pate, tree fuchsia and raukawa.

The stitchbird also supplements its diet with small insects.

Breeding

The stitchbird nests in cavities high up in old trees.[10] They are the only bird species that mates face to face,[11] in comparison to the more conventional copulation style for birds where the male mounts the female's back.[12] Stitchbird have some of the highest levels of extra-pair paternity of any bird with up to 79% of the chicks in the nest sired by other males, possibly as a result of forced copulations.[13]

Status and conservation

The stitchbird was relatively common early in the European colonisation of New Zealand, and began to decline relatively quickly afterwards, being extinct on the mainland and many offshore islands by 1885. The last sighting on the mainland was in the Tararua Range in the 1880s.[14] The exact cause of the decline is unknown, but is thought to be pressure from introduced species, especially black rats, and introduced avian diseases. Only a small population on Little Barrier Island survived. Starting in the 1980s the New Zealand Wildlife Service (now Department of Conservation) translocated numbers of individuals from Hauturu to other island sanctuaries to create separate populations. These islands were part of New Zealand's network of offshore reserves which have been cleared of introduced species and which protect other rare species including the kākāpō and takahē.

The world population is unknown; estimates for the size of the remnant population on Hauturu (Little Barrier Island) range from 600 to 6000 adult birds.[15] There are also translocated populations on Tiritiri Matangi Island, Kapiti Island, Zealandia, Maungatautari, Bushy Park and Lake Rotokare.[2] Attempts to establish populations on Hen Island, Cuvier Island and Mokoia Island and the Waitākere Ranges failed.[16] Reintroduction to these new sites has created genetic bottlenecks that have reduced genetic diversity in the newly founded populations and led to inbreeding.[17]

The Tiritiri Matangi population is one of the most successful reintroduced populations with relatively fast population growth and now stable at around 150 individuals.[18] Despite this, high levels of hatching failure (around 30% of all eggs fail to hatch) occur due to inbreeding.[19] Only the Little Barrier Island population (Te Hauturu-o-Toi) is self-sufficient and does not require intervention for the population to survive.[17] This species is classified as Vulnerable (D2) by the IUCN[1] because of its very small range and number of populations.

Reintroduction

In 2005, 60 stitchbirds were released into Zealandia (wildlife sanctuary) in Wellington and in October that year, three stitchbird chicks hatched there, the first time for more than 120 years that a stitchbird chick had been born on the mainland. The hatchings were described as a significant conservation milestone by sanctuary staff,[14] and in early 2019 Zealandia banded their 1000th hihi chick although the adult population is believed to remain at about 100 birds.[20]

In autumn 2007, 59 adult birds from the Tiritiri Matangi population were released in Cascade Kauri Park, in the Waitākere Ranges near Auckland[21][22] and by the end of the year the first chicks had fledged there.[21]

In 2017, 40 birds were released into the Lake Rotokare Scenic Reserve in Taranaki, with 17 chicks raised.[23] A further 30 were released in 2018.[23]

Gallery

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 BirdLife International (2017). "Notiomystis cincta". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T22704154A118814893. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22704154A118814893.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22704154/118814893. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Adams (2019).

- ↑ "Redlist - Stitchbird". https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22704154/214276713.

- ↑ Low, Matthew Richard (2004). "The Behavioural Ecology of Forced Copulation in the New Zealand Stitchbird (Hihi)". https://mro.massey.ac.nz/bitstream/10179/4157/1/02_whole.pdf.

- ↑ Barker et al. 2004

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Driskell et al. 2007

- ↑ Ewen et al., 2006

- ↑ Gregory, A. 2008

- ↑ Buller 1888, p. 102

- ↑ Rasch, 1985

- ↑ Anderson, 1993

- ↑ Ewen & Armstrong 2002

- ↑ Brekke, Patricia (2013). "Evolution of extreme-mating behaviour: Patterns of extrapair paternity in a species with forced extrapair copulation". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 67 (6): 963–972. doi:10.1007/s00265-013-1522-9.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 KWS 2005

- ↑ Hihi/Stichbird (Notiomystis cincta) recovery plan 2004–2009

- ↑ Castro (2016).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Brekke, Patricia (2011). "High genetic diversity in the remnant island population of hihi and the genetic consequences of re-introduction". Molecular Ecology 20 (1): 29–45. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04923.x. PMID 21073589. https://kar.kent.ac.uk/27513/1/Brekke%20et%20al%202011%20Molecular%20Ecology.pdf.

- ↑ Thorogood, Rose (2013). "The value of long-term ecological research: integrating knowledge for conservation of hihi on Tiritiri Matangi Island". New Zealand Journal of Ecology 37: 298–306.

- ↑ Brekke, Patricia (2010). "Sensitive males: inbreeding depression in an endangered bird". Proc. R. Soc. B 277 (1700): 3677–3684. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1144. PMID 20591862.

- ↑ "1000th hihi hatched at ZEALANDIA". https://www.visitzealandia.com/Whats-On/ArtMID/1150/ArticleID/172/1000th-hihi-hatched-at-ZEALANDIA.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Gregory, 2007

- ↑ BLI, 2007a

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Martin, Robyn (16 April 2018). "Hihi breed in Taranaki for first time in 130 years". Radio New Zealand. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/355182/hihi-breed-in-taranaki-for-first-time-in-130-years.

Sources

- Adams, L and Ewen, J (2019): Hihi Conservation: Annual Report of the Hihi Recovery Group http://www.hihiconservation.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Hihi_Conservation_2019_FINAL_smaller.pdf

- Angehr, George R. (1985): Stitchbird, NZ Wildlife Service

- Anderson, Sue (1993). "Stitchbirds copulate front to front". Notornis 40 (1): 14. http://www.notornis.org.nz/free_issues/Notornis_40-1993/Notornis_40_1_14.pdf.

- Barker, F.K.; Cibois, A.; Shikler, P.; Feinstein, J.; Cracraft, J. (2004). "Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 101 (30): 11040–11045. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401892101. PMID 15263073. Bibcode: 2004PNAS..10111040B.

- BirdLife International (BLI) (2007a): Hihi returns home after 125 years. Includes photo of adult male. Version of 23 February 2007. Retrieved 26 February 2007.

- Buller, Walter L. (1888): Fam. TIMELIPHGIDÆ — Pogonornis Cincta. — (Stitch-Bird.), in his A History of the Birds of New Zealand, Second Edition. London: Walter Buller. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- Castro, I. (2016). Stitchbird. In Miskelly, C.M. (ed.) New Zealand Birds Online. www.nzbirdsonline.org.nz

- Driskell, A.C.; Christidis, L.; Gill, B.; Boles, W.E.; Barker, F.K.; Longmore, N.W. (2007). "A new endemic family of New Zealand passerine birds: adding heat to a biodiversity hotspot". Australian Journal of Zoology 55 (2): 1–6. doi:10.1071/ZO07007.

- Ewen, J.G.; Armstrong, D.P. (2002). "Unusual sexual behaviour in the Stitchbird (or Hihi) Notiomystis cincta".". Ibis 144 (3): 530–531. doi:10.1046/j.1474-919X.2002.00079.x.

- Ewen, J.G.; Flux, I.; Ericson, P.G.P. (2006). "Systematic affinities of two enigmatic New Zealand passerines of high conservation priority, the hihi or stitchbird Notiomystis cincta and the kokako Callaeas cinerea". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 40 (1): 281–284. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.01.026. PMID 16527495. http://www.nrm.se/download/18.4e1d3ca810c24ddc7038000945/Ewen+et+al+Stitchbird+MPEV+2006.pdf.

- Gregory, Angela (2007): Waitakere hihi prepare for flight. New Zealand Herald 17 December 2007.

- Gregory, Angela (2007): Mysterious bird in a league of its own. New Zealand Herald 17 March 2008.

- Karori Wildlife Sanctuary (KWS) (2005): First hihi hatched in the wild on mainland NZ. Version of 2005-OCT-31. Retrieved 26 February 2007.

- Rasch, G (1985). "The ecology of cavity nesting in the stitchbird (Notiomystis cincta)".". New Zealand Journal of Zoology 12 (4): 637–642. doi:10.1080/03014223.1985.10428313.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Notiomystis cincta. |

- Karori Wildlife Sanctuary: Stitchbird Facts

- Birdlife International: Species factsheet

- "Hihi/stitchbird (Notiomystis cincta) recovery plan 2004–09 (Threatened Species Recovery Plan 54)". Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. 2005. http://www.doc.govt.nz/upload/documents/science-and-technical/TSRP54.pdf.

- Hihi conservation

Wikidata ☰ Q939459 entry

|