Biology:Pelobates syriacus

| Pelobates syriacus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Eastern spadefoot toad | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Anura |

| Family: | Pelobatidae |

| Genus: | Pelobates |

| Species: | P. syriacus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pelobates syriacus Boettger, 1889

| |

Pelobates syriacus, the eastern spadefoot or Syrian spadefoot, is a species of toad in the family Pelobatidae, native to an area extending from Eastern Europe to Western Asia.

Description

The eastern spadefoot is a plump toad with a large head with a flat topped skull, large, protruding eyes and vertical slit-like pupils. It can grow to a length of about 9 centimetres (3.5 in). The skin is smooth with a scattering of small warts. The male has a large gland at the back of his fore legs which becomes enlarged in the breeding season. The front foot has four toes and the back foot has five with deeply indented webbing between them. The hind legs are short and at the back of each hind foot is a yellowish bony protuberance, the inner metatarsal tubercle or spade, that gives the animal its name. The colour of the frog is quite variable, the back often being pale grey with large, greenish, irregularly shaped blotches and the belly being pale grey. The eastern spadefoot can be distinguished from the western spadefoot (Pelobates cultripes) by the colour of the spade which is black in the latter, and from the common spadefoot (Pelobates fuscus) by the fact that its head is not domed.[2][3]

Distribution

The eastern spadefoot is native to Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Georgia, Greece, Iran, Israel, Lebanon, Macedonia, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Syria and Turkey. It is quite common in Iran but is uncommon over much of its range. It is thought to be extinct in Jordan and its status is unclear in Albania, Iraq, Moldova and Ukraine .[1] Research led by the Palestine Museum of Natural History found it in the West Bank at Wadi Qana.[4]

Habitat

It lives in light woodland, bushy and semi-desert areas, badlands, arable fields and dunes. It prefers loose soil where it can use its spades to dig the burrow in which it lives, but is also found in rocky areas and pebbly clay soils.[3] The range of eastern spadefoot is limited by mean annual temperature and rainfall (the species does not live in the areas with insufficient summer temperature and in areas with a high rainfall level), but the northern distribution limit may additionally depend on the distribution of common spadefoot.[5] Because the species has large tadpoles, the distribution is additionally limited by presence of sufficiently large but fishless ponds.[5]

Voice

The eastern spadefoot has a distinctive call, usually emitted from underwater and often continuing all night. It is a rapid, staccato "clock...clock...clock" that is audible from some way away.[2]

Biology

The eastern spadefoot is nocturnal and returns to the same lair each night when it has finished foraging for molluscs, spiders, insects and other small arthropods. As well as digging its own burrow, it sometimes makes use of a rodent hole or a crevice under a rock. At times when the air temperature is very hot it retires to the deepest part of its burrow and may aestivate in mid-summer.[3] At these times the toads that live in the moist soil of riverbanks may fare better than those elsewhere and in times of drought, there may be a high mortality rate among toads.[3]

In the winter it hibernates among tree roots or under rocks, sometimes several toads huddling together. Breeding takes place from February to May depending on location. Ditches and stagnant pools are favoured locations for amplexus. Several thousand eggs are laid in broad bands of gelatinous material that may be 2 cm (0.8 in) thick and 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) long. The tadpoles hatch after three days, eat algae and water weeds and grow for three or four months before they undergo metamorphosis into juvenile toads. Many of these burrow into the mud at the edge of ponds to overwinter but some may overwinter as tadpoles.[2][3]

Status

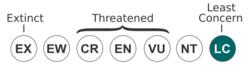

The eastern spadefoot is considered of "Least concern" by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. The chief threat it faces is habitat loss due to changes in land use and the drainage of areas in which it breeds. It has a wide distribution and is believed to have a large population, so, although its range is rather fragmented, it is thought to be declining sufficiently slowly as to not need to be listed in a more threatened category. However, some of its separate populations are susceptible to local extinction due to adverse conditions, especially in arid areas.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Aram Agasyan, Boris Tuniyev, Jelka Crnobrnja Isailovic, Petros Lymberakis, Claes Andrén, Dan Cogalniceanu, John Wilkinson, Natalia Ananjeva, Nazan Üzüm, Nikolai Orlov, Richard Podloucky, Sako Tuniyev, Uğur Kaya (2009). "Pelobates syriacus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2009: e.T58053A11723660. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009.RLTS.T58053A11723660.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/58053/11723660. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Arnold, Nicholas; Ovenden, Denys (2002). Reptiles and Amphibians of Britain and Europe. London: Harper Collins Publishers Ltd.. p. 70.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Pelobates syriacus AmphibiaWeb. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ↑ Qumsiyeh, Mazin B.; Handal, Elias N.; Al-Sheikh, Banan; Najajreh, Mohammad H.; Albaradeiya, Issa Musa (2022-12-03). "Designating the First Vernal Pool Micro-Reserve in a Buffer Zone of Wadi Qana Protected Area, Palestine" (in en). Wetlands 42 (8): 119. doi:10.1007/s13157-022-01644-5. ISSN 1943-6246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-022-01644-5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Tarkhnishvili, D; Serbinova, I; Gavashelishvili, A (2009). "Modelling the range of Syrian spadefoot toad (Pelobates syriacus) with combination of GIS-based approaches". Amphibia-Reptilia 30 (3): 401–412. doi:10.1163/156853809788795137.

Wikidata ☰ Q1187199 entry

|