Biology:Penghusuchus

| Penghusuchus | |

|---|---|

| |

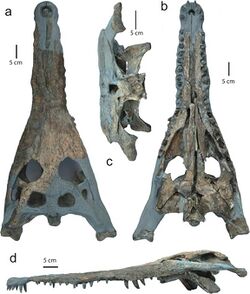

| Skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Archosauriformes |

| Order: | Crocodilia |

| Family: | Gavialidae |

| Genus: | †Penghusuchus Shan et al., 2009 |

| Type species | |

| †Penghusuchus pani Shan et al., 2009

| |

Penghusuchus is an extinct genus of gavialid crocodylian. It is known from a skeleton found in Middle to Upper Miocene rocks of Penghu Island, off Taiwan. The taxon was described in 2009 by Shan and colleagues; the type species is P. pani.[2] It may be related to two other fossil Asian gavialids: Toyotamaphimeia machikanensis of Japan and Hanyusuchus sinensis of South China.[3] It was a medium-sized gavialid with an estimated total length of 4.5 metres (15 ft).[4]

Discovery

On 25 March 2006, on the coast of Neian, Shiyu, Penghu Islands, an excavator driver Mr. Ming-Kuo Pan found a fossilized crocodylian tooth exposed in the sandstone interlayer between basaltic rocks and then dug up a whole skeleton. The skeleton is 70% complete and was found in the Yuwentao Formation of the middle Miocene (more than 10 million years ago), and its sedimentary rocks were dated as 17-15 million years ago, according to the pollen dating in the stratum, making it one of the oldest and most complete vertebrate fossils known in Taiwan. The genus name is derived from its discovery site in Penghu, and the species name honored its discoverer, Mr. Ming-Kuo Pan. It is now considered to represent a unique and extinct gavialid clade in East Asia, along with the Pleistocene Toyotamaphimeia from Japan and Taiwan and the Holocene Hanyusuchus from South China.[3][5][6][7][8]

Morphological Description

Penghusuchus has several diagnostic characters, including: anterior process of jugal, prefrontal and lacrimal is extending as the same level; anterior process of frontal truncated and attach with nasals in W-shaped; choana is triangular with a sharp anterior angle, and its lateral borders and floor of nasopharyngeal duct form Y-shaped ridge-like prominence on ventral surface of pterygoid; presence of five maxillary teeth within the range of the suborbital fenestra; 7th maxillary tooth is the largest in the first wave of maxillary teeth and maxilla is bulges; angular with a mid-dorsal process excluding surangular from posterodorsal border of external mandibular fenestra. Among these characters, the largest 7th maxillary tooth is only present on Pleistocene Toyotamaphimeia from Japan and Taiwan and the Holocene Hanyusuchus from South China, suggest a unique shared-featured of these three East-Asian taxa. Still, the size of Penghusuchus (4.5–5 m) is estimated smaller than Hanyusuchus and theToyotamaphimeia (may over 6 m), as well as some of the characters is differ from the latter two.[3][5][6][7][8]

Although been long classified as Tomistominae, a 2019 study noted that Penghusuchus and Toyotamaphimeia both have gavialine features, with the Penghusuchus present the following features: axial diapophysis is present on axial neural arch; paired, bifurcated hypapophysis on the ventral side of vertebrae centrum; iliac blade has a prominent anterior process; development of deltopectoral crest in the humerus is weak; midline dorsal or pelvic osteoderms is rectangular and wider than long; thick basioccipital tubera with participating of the robust exoccipital ventral process; the cranio-quadrate passage on the occipital surface is obscured by the convex process of the exoccipital; the splenial symphysis of the mandible extends to the length of about 5-7 teeth and forms a broad or narrow V in dorsal view. These characters are usually observed in gavialid, suggesting that these two East Asian taxa share mosaic features of both tomistomine and gavialid, filling the evolutionary gap of the two longeirostrine crocodylians.[8]

Based the vertebrae length, the total length of Penghusuchus is estimated as 4.5 metres. The holotype of Penghusuchus is an osteological mature individual and reached sexual maturity based on its neurocentral suture in precaudal vertebrae is closed.[4]

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram based morphological studies comparing skeletal features that shows Penghusuchus as a member of Tomistominae, related to the false gharial:[9]

| Crocodylidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Based on morphological studies of extinct taxa, the tomistomines (including the living false gharial) were long thought to be classified as crocodiles and not closely related to gavialoids.[10] However, recent molecular studies using DNA sequencing have consistently indicated that the false gharial (Tomistoma) (and by inference other related extinct forms in Tomistominae) actually belong to Gavialoidea (and Gavialidae).[11][12][13][14][15][16][17]

Below is a cladogram from a 2018 tip dating study by Lee & Yates simultaneously using morphological, molecular (DNA sequencing), and stratigraphic (fossil age) data that shows Penghusuchus as a gavialid, related to both the gharial and the false gharial:[16]

| Gavialidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Iijima and his colleagues named Hanyusuchus from Holocene South China. The phylogenetic analysis Penghusuchus pani, Hanyusuchus sinensis and Toyotamaphimeia machikanensis formed a monophyletic group.[3]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ Rio, Jonathan P.; Mannion, Philip D. (6 September 2021). "Phylogenetic analysis of a new morphological dataset elucidates the evolutionary history of Crocodylia and resolves the long-standing gharial problem". PeerJ 9: e12094. doi:10.7717/peerj.12094. PMID 34567843.

- ↑ Shan, Hsi-yin; Wu, Xiao-chun; Cheng, Yen-nien; Sato, Tamaki (2009). "A new tomistomine (Crocodylia) from the Miocene of Taiwan". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 46 (7): 529–555. doi:10.1139/E09-036. Bibcode: 2009CaJES..46..529S.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Iijima, Masaya; Qiao, Yu; Lin, Wenbin; Peng, Youjie; Yoneda, Minoru; Liu, Jun (2022-03-09). "An intermediate crocodylian linking two extant gharials from the Bronze Age of China and its human-induced extinction" (in en). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 289 (1970). doi:10.1098/rspb.2022.0085. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 8905159. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rspb.2022.0085.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Iijima, M.; Kubo, T. (2020). "Vertebrae-Based Body Length Estimation in Crocodylians and Its Implication for Sexual Maturity and the Maximum Sizes". Integrative Organismal Biology 2 (1): obaa042. doi:10.1093/iob/obaa042.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Yoshitsugu, Kobayashi; Yukimitsu, Tomida; Tadao, Kamei; Taro, Eguchi (2006). "ANATOMY OF A JAPANESE TOMISTOMINE CROCODYLIAN, TOYOTAMAPHIMEIA MACHIKANENSIS (KAMEI ET MATSUMOTO, 1965), FROM THE MIDDLE PLEISTOCENE OF OSAKA PREFECTURE : THE REASSESSMENT OF ITS PHYLOGENETIC STATUS WITHIN CROCODYLIA" (in en). National Science Museum monographs 35: i–121. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1573105977361256576.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Iijima, Masaya; Momohara, Arata; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Hayashi, Shoji; Ikeda, Tadahiro; Taruno, Hiroyuki; Watanabe, Katsunori; Tanimoto, Masahiro et al. (May 2018). "Toyotamaphimeia cf. machikanensis (Crocodylia, Tomistominae) from the Middle Pleistocene of Osaka, Japan, and crocodylian survivorship through the Pliocene-Pleistocene climatic oscillations" (in en). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 496: 346–360. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.02.002. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0031018217311124.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ito, Ai; Aoki, Riosuke; Hirayama, Ren; Yoshida, Masataka; Kon, Hiroo; Endo, Hideki (April 2018). "The Rediscovery and Taxonomical Reexamination of the Longirostrine Crocodylian from the Pleistocene of Taiwan" (in en). Paleontological Research 22 (2): 150–155. doi:10.2517/2017PR016. ISSN 1342-8144. http://www.bioone.org/doi/10.2517/2017PR016.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Iijima, Masaya; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu (December 2019). "Mosaic nature in the skeleton of East Asian crocodylians fills the morphological gap between "Tomistominae" and Gavialinae" (in en). Cladistics 35 (6): 623–632. doi:10.1111/cla.12372. ISSN 0748-3007. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cla.12372.

- ↑ Iijima, Masaya; Momohara, Arata; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Hayashi, Shoji; Ikeda, Tadahiro; Taruno, Hiroyuki; Watanabe, Katsunori; Tanimoto, Masahiro et al. (2018-05-01). "Toyotamaphimeia cf. machikanensis (Crocodylia, Tomistominae) from the Middle Pleistocene of Osaka, Japan, and crocodylian survivorship through the Pliocene-Pleistocene climatic oscillations" (in en). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 496: 346–360. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.02.002. ISSN 0031-0182. Bibcode: 2018PPP...496..346I. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031018217311124.

- ↑ Brochu, C.A.; Gingerich, P.D. (2000). "New tomistomine crocodylian from the Middle Eocene (Bartonian) of Wadi Hitan, Fayum Province, Egypt". University of Michigan Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology 30 (10): 251–268.

- ↑ Harshman, J.; Huddleston, C. J.; Bollback, J. P.; Parsons, T. J.; Braun, M. J. (2003). "True and false gharials: A nuclear gene phylogeny of crocodylia". Systematic Biology 52 (3): 386–402. doi:10.1080/10635150309323. PMID 12775527. http://si-pddr.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/6275/2003C_Harshman_et_al.pdf.

- ↑ Gatesy, Jorge; Amato, G.; Norell, M.; DeSalle, R.; Hayashi, C. (2003). "Combined support for wholesale taxic atavism in gavialine crocodylians". Systematic Biology 52 (3): 403–422. doi:10.1080/10635150309329. PMID 12775528. http://www.faculty.ucr.edu/~mmaduro/seminarpdf/GatesyetalSystBiol2003.pdf.

- ↑ Willis, R. E.; McAliley, L. R.; Neeley, E. D.; Densmore Ld, L. D. (June 2007). "Evidence for placing the false gharial (Tomistoma schlegelii) into the family Gavialidae: Inferences from nuclear gene sequences". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 43 (3): 787–794. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.02.005. PMID 17433721.

- ↑ Gatesy, J.; Amato, G. (2008). "The rapid accumulation of consistent molecular support for intergeneric crocodylian relationships". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 48 (3): 1232–1237. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.02.009. PMID 18372192.

- ↑ Erickson, G. M.; Gignac, P. M.; Steppan, S. J.; Lappin, A. K.; Vliet, K. A.; Brueggen, J. A.; Inouye, B. D.; Kledzik, D. et al. (2012). Claessens, Leon. ed. "Insights into the ecology and evolutionary success of crocodilians revealed through bite-force and tooth-pressure experimentation". PLOS ONE 7 (3): e31781. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031781. PMID 22431965. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...731781E.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Michael S. Y. Lee; Adam M. Yates (27 June 2018). "Tip-dating and homoplasy: reconciling the shallow molecular divergences of modern gharials with their long fossil". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 285 (1881). doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.1071. PMID 30051855.

- ↑ Hekkala, E.; Gatesy, J.; Narechania, A.; Meredith, R.; Russello, M.; Aardema, M. L.; Jensen, E.; Montanari, S. et al. (2021-04-27). "Paleogenomics illuminates the evolutionary history of the extinct Holocene "horned" crocodile of Madagascar, Voay robustus" (in en). Communications Biology 4 (1): 505. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-02017-0. ISSN 2399-3642. PMID 33907305.

Wikidata ☰ Q12780125 entry

|