Biology:Postmenopausal confusion

Postmenopausal confusion is a symptom of menopause in which women face problems with cognition during and after menopause due to hormonal imbalances.

Causes

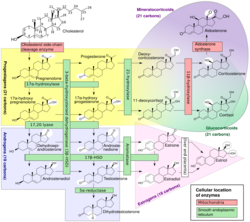

Estrogen affects the serotonergic, cholinergic, dopaminergic, and noradrenergic systems, all of which are key to maintaining regular functioning in both survival and cognition. Serotonin and dopamine also play key roles in mood, which alters drastically with menopause as these hormone levels decrease, as a result of estrogen decline. Furthermore, the ratio of testosterone to estrogen changes as testosterone is now of higher quantity, causing a more easily angered disposition and allowing stress to seem more prevalent than before menopause.[1]

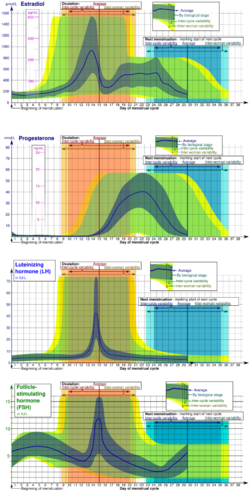

During menopause, the amygdala, which controls emotion, and the prefrontal cortex, which regulates judgment, become more regular.[1] Estrogens, a group of hormones including estradiol and estrone, are secreted by the ovaries and the secretion is regulated by luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), both of which are produced by the pituitary gland. In women, estrogen levels fluctuate during the menstrual cycle but reach a steady decline and then remain at low levels postmenopause.[2]

Behavioral studies suggest that estradiol augments cognition that occurs within the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. It can also enhance long term potentiation (LTP) which is key at the neurocellular level for memory and learning and is mostly affected at the neuroanatomical level of CA1 pyramidal cells, NMDAr receptors, and AMPAr receptors.[3]

Microglia are glial cells in the brain that make estrogen and produce cytokines and immune proteins in response to estrogen.[4] These cells play a large role in neuroinflammation which can in turn lead to disorders such as Multiple Sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease. Estrogen can play an anti-inflammatory role with microglia, which can protect the CNS against the stimuli that promote such diseases.[5]

Endorphins modify core body temperature and trigger mechanisms which allow the body to reduce heat such as sweating and sending blood closer to the body's surface where the blood can be cooled.[6] Postmenopausal symptoms such as hot flushes and night sweats initiated by the fluctuation in endorphins, may cause stress, leading to negativity, depression, and anxiety, which in turn can lead to cognitive decline.[7]

At the cellular level, oestrogen binds to nuclear receptors, such as oestrogen receptors ER α/β, and acts as a transcription factor. It increases the production of anti-apoptotic proteins and prevents the initiation of apoptosis. It also activates antioxidants which work as defenses reducing negative factors such as glutathione levels and oxidative DNA damage in mitochondria.[8] This programmed cell death and other damage of mitochondria has long been found as a key mechanism in Alzheimer's.[9]

The decline in estrogens during menopause, which in turn produces a decrease in glucose, is shown in the prefontal cortex as well as the posterior cingulate.[2][10] Alzheimer's patients have been shown to have abnormal glucose metabolism in these areas, also adding to the conclusion that estrogen has a direct relation to the development of Alzheimer's.[2][11]

Treatment

Hormone therapy also known as estrogen therapy is the most common treatment for menopausal symptoms.

Cognition

Estrogen has direct effects on the hippocampus, which in turn relates to mood, including increasing dendritic spine density and increasing the volume and neurogenesis of the hipposcampus; these are key to greater cognition as key neuronal circuits are maintained.[7] Pharmaceutical companies are currently developing estrogen receptor ligands as anti-inflammatory agents to reduce neuroinflammation of microglia which leads to neurodegenerative disorders. However, other cellular targets may overtake the focus of the estrogen treatment as estrogen works as an anti-apoptotic hormone for neurons, induces growth of neural stem cells, increases astroglial cells ability to secrete neuroprotective molecules while also reducing their formation of neurotoxins, and reduces adhesion to endothelial cells.[5]

The most common treatment is hormone replacement therapy or estrogen therapy. Women using hormone therapy for at least two years have increased blood flow to the hippocampus and temporal lobe as compared to those who did not undergo therapy.[7][12] These areas of the brain are key to memory.[13] Also, women who do not undergo therapy have been found to have less metabolic activity in the posterior cingulate cortex, while those with estrogen therapy did not show a significant metabolic change. This is important as declines in cerebral metabolism occur in the early stages of Alzheimer's, as mentioned in "Causes".[14] Women who had their uterus and ovaries removed for medical reasons and lost their gonadal hormones showed a decrease in short-term verbal (hippocampus) and working memories (pre-frontal cortex), yet with estrogen therapy the memory loss was prevented.[13][15][16] Furthermore, those who have undertaken estrogen therapy have shown significantly higher scores on verbal memory, verbal fluency, and visual memory tasks as compared to those who did not undergo treatment.[17][18] It is widely found that this treatment must be administered near to the onset of menopause as opposed to several years postmenopause, when hormone therapy can have detrimental effects on cognition.[2][5][7]

Research is inconclusive as to the true effects of estrogen on hippocampal volume as studies show results differing from improved cognition and maintained hippocampal volume when hormone therapy is administered during menopause to results showing no obvious beneficial results.[19]

History

Research on menopause as a whole declined with the end of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) studies, but research on the treatment of symptoms associated with menopause—especially the treatment of cognitive decline—continues. New research refutes the WHI findings that estrogen therapy (ET) is not a useful treatment for menopausal symptoms.[3] This is especially shown in Alzheimer's research as the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study refuted the argument that a decline in oestrogens and progestogens seen during menopause increases vulnerability to neurodegenerative diseases.[9] Mice are the main subject for research involving the effects of estrogen on brain health, cognition, and neurodegenerative disorders, and research in this area continues.[5][9]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Brizendine, Louann (2006). The female brain. New York: Broadway Books. pp. 135–57.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Rettberg, Jamaica R.; J. Yao; R.D. Brinton (2013). "Estrogen: A master regulator of bioenergetic systems in the brain and body". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 35 (1): 8–30. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.08.001. PMID 23994581.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mott, Natasha N.; Toni R. Pak (2013). "Estrogen Signaling and the Aging Brain: Context-Dependent Consideration for Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy". ISRN Endocrinology 2013: 1–16. doi:10.1155/2013/814690. PMID 23936665.

- ↑ Silva, Ivaldo; Frederick Naftolin (2013). "Brain health and cognitive and mood disorders in ageing women". Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology 27 (5): 661–672. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.06.005. PMID 24007951.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Vegeto, Elisabetta; V. Benedusi; A. Maggi (2008). "Estrogen ati-inflammatory activity in brain: a therapeutic opportunity for menopause and neurodegenerative diseases". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 29 (4): 507–519. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.04.001. PMID 18522863.

- ↑ Roush, Karen (2012). "Managing menopausal symptoms". American Journal of Nursing 112 (6): 28–35. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000415120.76982.7a. PMID 22584467.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Wharton, Whitney; C. E. Gleason; S. R. M. S. Olson; C. M. Carlsson; S. Asthana (2012). "Neurobiological underpinnings of the estrogen- mood relationship". Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 8 (3): 247–256. doi:10.2174/157340012800792957. PMID 23990808.

- ↑ Borras, C.; J. Sastre; D. Garcia-Sala; A. Lloret; F.V. Pallardo; J. Vina (2003). "Mitochondria from females exhibit higher antioxidant gene expression and lower oxidative damage than males". Free Radical Biology & Medicine 34 (3): 546–552. doi:10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01356-4. PMID 12614843.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Grimm, A.; Y. Lim; A.G. Mensah-Nyagan; J. Götz; A. Eckert (2012). "Alzheimer's disease, oestrogen and mitochondria: an ambiguous relationship". Molecular Neurobiology 46 (1): 151–160. doi:10.1007/s12035-012-8281-x. PMID 22678467.

- ↑ [unreliable medical source?] Rasgon, N.L.; Silverman, D.; Siddarth, P.; Miller, K.; Ercoli, L.M.; Elman, S.; Lavretsky, H.; Huang, S.C. et al. (2005). "Estrogen use and brain metabolic change in postmenopausal women". Neurobiology of Aging 26 (2): 229–235. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.03.003. PMID 15582750.

- ↑ [unreliable medical source?] Vaishnavi, S.N.; Vlassenko, A.G.; Rundle, M.M.; Snyder, A.Z.; Mintun, M.A.; Raichle, M.E. (2010). "Regional aerobic glycolysis in the human brain". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107 (41): 17757–17762. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010459107. PMID 20837536. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..10717757V.

- ↑ Maki, PM (2005). "Estrogen effects on the hippocampus and frontal lobes". International Journal of Fertility and Women's Medicine 50 (2): 67–71. PMID 16334413.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Maki, P.M.; S.M.Resnick (2001). "Effects of estrogen on patterns of brain activity at rest and during cognitive activity: a review of neuroimaging studies". NeuroImage 14 (2): 789–801. doi:10.1006/nimg.2001.0887. PMID 11554798.

- ↑ Brinton, Roberta Diaz (2008). "Estrogen-induced plasticity from cells to circuits: predictions for cognitive function". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 30 (4): 212–221. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2008.12.006. PMID 19299024.

- ↑ Sherwin, Barbara B. (1999). "Can estrogen keep you smart? Evidence from clinical studies". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience 24 (4): 315–321. PMID 10516798.

- ↑ Sherwin, B.B.; J.F. Henry (2008). "Brain aging modulate the neuroprotective efects of estrogen on selective aspects of cognition in women: a critical review". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 29 (1): 88–113. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.08.002. PMID 17980408.

- ↑ Maki, P.M.; A.B. Zonderman; S.M. Resnick (2001). "Enhanced verbal memory in nondemented elderly women receiving hormone-replacement therapy". American Journal of Psychiatry 158 (2): 227–233. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.227. PMID 11156805.

- ↑ Genazzani, A.R.; N. Pluchino; S. Luisi; M. Luisi (2007). "Estrogen, cognition and female ageing". Human Reproduction Update 13 (2): 176–185. doi:10.1093/humupd/dml042. PMID 17135285.

- ↑ Wnuk, A.; D.L. Korol; K.I. Erickson (2012). "Estrogens, hormone therapy, and hippocampal volume in postmenopausal women". Maturitas 73 (3): 186–190. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.07.001. PMID 22858056.

Further reading

- Rao, Y.S.; Mott, N.N.; Wang, Y.; Chung, W.C.; Pak, T.R. (2013). "MicroRNAs in the aging female brain: a putative mechanism for age-specific estrogen effects". Endocrinology 154 (8): 2795–2806. doi:10.1210/en.2013-1230. PMID 23720423.

- Shafin, N.; Zakaria, R.; Hussain, N.H.; Othman, Z. (2013). "Association of oxidative stress and memory performance in postmenopausal women receiving estrogen progestin therapy". Menopause 20 (6): 661–666. doi:10.1097/GME.0b013e31827758c6. PMID 23715378. http://eprints.usm.my/44480/1/10.1097%40gme.0b013e31827758c6.pdf.

- Epperson, C.N.; Sammel, M.D.; Freeman, E.W. (2013). "Menopause effects on verbal memory: findings from a longitudinal community cohort". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 98 (9): 3829–3838. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-1808. PMID 23836935.

- Sherwin, Barbara B.; Miglena Grigorova (2011). "Differential effects of estrogen and micronized progesterone or medroxyprogesterone acetate on cognition in postmenopausal women". Fertility and Sterility 96 (2): 399–403. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.079. PMID 21703613.

- Epperson, C.N.; Amin, Z.; Ruparel, K.; Gur, R.; Loughead, J. (2012). "Interactive effects of estrogen and serotonin on brain activation during working memory and affective processing in menopausal women". Psychoneuroendocrinology 37 (3): 372–382. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.07.007. PMID 21820247.

- Hampson, Elizabeth; E.E. Morley (2013). "Estradiol concentrations and working memory performance in women of reproductive age". Psychoneuroendocrinology 38 (12): 2897–2904. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.07.020. PMID 24011502.

- Hunter, Myra S.; Joseph Chilcot (2013). "Testing a cognitive model of menopausal hot flushes and night sweats". Journal of Psychosomatic Research 74 (4): 307–312. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.12.005. PMID 23497832.

|