Biology:Premotor cortex

| Premotor cortex | |

|---|---|

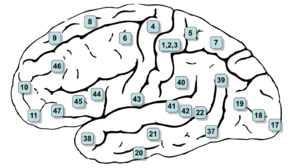

Image of brain with Brodmann areas numbered | |

| |

| Details | |

| Part of | The brain |

| Artery | Middle cerebral artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cortex praemotorius |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

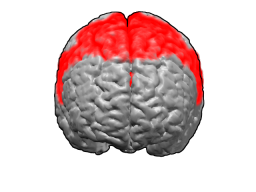

The premotor cortex is an area of the motor cortex lying within the frontal lobe of the brain just anterior to the primary motor cortex. It occupies part of Brodmann's area 6. It has been studied mainly in primates, including monkeys and humans. The functions of the premotor cortex are diverse and not fully understood. It projects directly to the spinal cord and therefore may play a role in the direct control of behavior, with a relative emphasis on the trunk muscles of the body. It may also play a role in planning movement, in the spatial guidance of movement, in the sensory guidance of movement, in understanding the actions of others, and in using abstract rules to perform specific tasks. Different subregions of the premotor cortex have different properties and presumably emphasize different functions. Nerve signals generated in the premotor cortex cause much more complex patterns of movement than the discrete patterns generated in the primary motor cortex.

Structure

The premotor cortex occupies the part of Brodmann area 6 that lies on the lateral surface of the cerebral hemisphere. The medial extension of area 6, onto the midline surface of the hemisphere, is the site of the supplementary motor area, or SMA.

The premotor cortex can be distinguished from the primary motor cortex, Brodmann area 4, just posterior to it, based on two main anatomical markers. First, the primary motor cortex contains giant pyramidal cells called Betz cells in layer V, whereas giant pyramidal cells are less common and smaller in the premotor cortex. Second, the primary motor cortex is agranular: it lacks a layer IV marked by the presence of granule cells. The premotor cortex is dysgranular: it contains a faint layer IV.

The premotor cortex can be distinguished from Brodmann area 46 of the prefrontal cortex, just anterior to it, by the presence of a fully formed granular layer IV in area 46. The premotor cortex is therefore anatomically a transition between the agranular motor cortex and the granular, six-layered prefrontal cortex.

The premotor cortex has been divided into finer subregions on the basis of cytoarchitecture (the appearance of the cortex under a microscope), cytohistochemistry (the manner in which the cortex appears when stained by various chemical substances), anatomical connectivity to other brain areas, and physiological properties.[1][2][3][4] These divisions are summarized below in Divisions of the premotor cortex.

The connectivity of the premotor cortex is diverse, partly because the premotor cortex itself is heterogenous and different subregions have different connectivity. Generally the premotor cortex has strong afferent (input) and efferent (output) connectivity to the primary motor cortex, the supplementary motor area, the superior and inferior parietal cortex, and prefrontal cortex. Subcortically it projects to the spinal cord, the striatum, and the motor thalamus among other structures.

In the study of neurolinguistics, the ventral premotor cortex has been implicated in motor vocabularies in both speech and manual gestures. A mental syllabary — a repository of gestural scores for the most highly used syllables in a language — has been linked to the ventral premotor cortex in a large-scale meta-analysis of functional imaging studies[citation needed]. A recent prospective fMRI study that was designed to distinguish phonemic and syllable representations in motor codes provided further evidence for this view by demonstrating adaptation effects in the ventral premotor cortex to repeating syllables[citation needed].

The premotor cortex is now generally divided into four sections.[2][3][5] First it is divided into an upper (or dorsal) premotor cortex and a lower (or ventral) premotor cortex. Each of these is further divided into a region more toward the front of the brain (rostral premotor cortex) and a region more toward the back (caudal premotor cortex). A set of acronyms are commonly used: PMDr (premotor dorsal, rostral), PMDc (premotor dorsal, caudal), PMVr (premotor ventral, rostral), PMVc (premotor ventral, caudal). Some researchers, especially those who study the ventral premotor areas, use a different terminology. Field 7 or F7 denotes PMDr; F2 = PMDc; F5=PMVr; F4=PMVc.

These subdivisions of premotor cortex were originally described and remain primarily studied in the monkey brain. Exactly how they may correspond to areas of the human brain, or whether the organization in the human brain is somewhat different, is not yet clear.

PMDc (F2)

PMDc is often studied with respect to its role in guiding reaching.[6][7][8] Neurons in PMDc are active during reaching. When monkeys are trained to reach from a central location to a set of target locations, neurons in PMDc are active during the preparation for the reach and also during the reach itself. They are broadly tuned, responding best to one direction of reach and less well to different directions. Electrical stimulation of the PMDc on a behavioral time scale was reported to evoke a complex movement of the shoulder, arm, and hand that resembles reaching with the hand opened in preparation to grasp.[9]

PMDr(F7)

PMDr may participate in learning to associate arbitrary sensory stimuli with specific movements or learning arbitrary response rules.[10][11][12] In this sense, it may resemble the prefrontal cortex more than other motor cortex fields. It may also have some relation to eye movement. Electrical stimulation in the PMDr can evoke eye movements[13] and neuronal activity in the PMDr can be modulated by eye movement.[14]

PMVc(F4)

PMVc or F4 is often studied with respect to its role in the sensory guidance of movement. Neurons here are responsive to tactile stimuli, visual stimuli, and auditory stimuli.[15][16][17][18] These neurons are especially sensitive to objects in the space immediately surrounding the body, in so-called peripersonal space. Electrical stimulation of these neurons causes an apparent defensive movement as if protecting the body surface.[19][20] This premotor region may be part of a larger circuit for maintaining a margin of safety around the body and guiding movement with respect to nearby objects.[21]

PMVr(F5)

PMVr or F5 is often studied with respect to its role in shaping the hand during grasping and in interactions between the hand and the mouth.[22][23] Electrical stimulation of at least some parts of F5, when the stimulation is applied on a behavioral time scale, evokes a complex movement in which the hand moves to the mouth, closes in a grip, orients such that the grip faces the mouth, the neck turns to align the mouth to the hand, and the mouth opens.[9][19]

Mirror neurons were first discovered in area F5 in the monkey brain by Rizzolatti and colleagues.[24][25] These neurons are active when the monkey grasps an object. Yet the same neurons become active when the monkey watches an experimenter grasp an object in the same way. The neurons are therefore both sensory and motor. Mirror neurons are proposed to be a basis for understanding the actions of others by internally imitating the actions using one's own motor control circuits.

History

In the earliest work on the motor cortex, researchers recognized only one cortical field involved in motor control. Campbell[26] in 1905 was the first to suggest that there might be two fields, a "primary" motor cortex and an "intermediate precentral" motor cortex. His reasons were largely based on cytoarchitectonics. The primary motor cortex contains cells with giant cell bodies known as "Betz cells". The Betz cells are rare or absent in the adjacent cortex.

On similar criteria Brodmann[27] in 1909 also distinguished between his area 4 (coextensive with the primary motor cortex) and his area 6 (coextensive with the premotor cortex).

Vogt and Vogt[1][2] in 1919 also suggested that motor cortex was divided into a primary motor cortex (area 4) and a higher-order motor cortex (area 6) adjacent to it. Furthermore, in their account, area 6 could be divided into 6a (the dorsal part) and 6b (the ventral part). The dorsal part could be further divided into 6a-alpha (a posterior part adjacent to the primary motor cortex) and 6a-beta (an anterior part adjacent to the prefrontal cortex). These cortical fields formed a hierarchy in which 6a-beta controlled movement at the most complex level, 6a-alpha had intermediate properties, and the primary motor cortex controlled movement at the simplest level. Vogt and Vogt are therefore the original source of the idea of a caudal (6a-alpha) and a rostral (6a-beta) premotor cortex.

Fulton[28] in 1935 helped to solidify the distinction between a primary motor map of the body in area 4 and a higher-order premotor cortex in area 6. His main evidence came from lesion studies in monkeys. It is not clear where the term "premotor" came from or who used it first, but Fulton popularized the term.

A caveat about the premotor cortex, noted early in its study, is that the hierarchy between the premotor cortex and the primary motor cortex is not absolute. Instead both the premotor cortex and primary motor cortex project directly to the spinal cord, and each has some capability to control movement even in the absence of the other. Therefore, the two cortical fields operate at least partly in parallel rather than in a strict hierarchy. This parallel relationship was noted as early as 1919 by Vogt and Vogt[1][2] and also emphasized by Fulton.[28]

Penfield[29] in 1937 notably disagreed with the idea of a premotor cortex. He suggested that there was no functional distinction between a primary motor and a premotor area. In his view both were part of the same map. The most posterior part of the map, in area 4, emphasized the hand and fingers and the most anterior part, in area 6, emphasized the muscles of the back and neck.

Woolsey[30] who studied the motor map in monkeys in 1956 also believed there was no distinction between primary motor and premotor cortex. He used the term M1 for the proposed single map that encompassed both the primary motor cortex and the premotor cortex. He used the term M2 for the medial motor cortex now commonly known as the supplementary motor area. (Sometimes in modern reviews M1 is incorrectly equated with the primary motor cortex.)

Given this work by Penfield on the human brain and by Woolsey on the monkey brain, by the 1960s the idea of a lateral premotor cortex as separate from the primary motor cortex had mainly disappeared from the literature. Instead M1 was considered to be a single map of the body, perhaps with complex properties, arranged along the central sulcus.

Re-emergence

The hypothesis of a separate premotor cortex re-emerged and gained ground in the 1980s. Several key lines of research helped to establish the premotor cortex by showing that it had properties distinct from those of the adjacent primary motor cortex.

Roland and colleagues[31][32] studied the dorsal premotor cortex and the supplementary motor area in humans while blood flow in the brain was monitored in a positron emission scanner. When people made complex sensory-guided movements such as following verbal instructions, more blood flow was measured in the dorsal premotor cortex. When people made internally paced sequences of movements, more blood flow was measured in the supplementary motor area. When people made simple movements that required little planning, such as palpating an object with the hand, the blood flow was more limited to the primary motor cortex. By implication, the primary motor cortex was more involved in execution of simple movement, the premotor cortex was more involved in sensory guided movement, and the supplementary motor area was more involved in internally generated movements.

Wise and his colleagues[10][33] studied the dorsal premotor cortex of monkeys. The monkeys were trained to perform a delayed response task, making a movement in response to a sensory instruction cue. During the task, neurons in the dorsal premotor cortex became active in response to the sensory cue and often remained active during the few seconds of delay or preparation time before the monkey performed the instructed movement. Neurons in the primary motor cortex showed much less activity during the preparation period and were more likely to be active only during the movement itself. By implication, the dorsal premotor cortex was more involved in planning or preparing for movement and the primary motor cortex more involved in executing movement.

Rizzolatti and colleagues[3] divided the premotor cortex into four parts or fields based on cytoarchitectonics, two dorsal fields and two ventral fields. They then studied the properties of the ventral premotor fields, establishing tactile, visual, and motor properties of a complex nature (summarized in greater detail above in Divisions of the premotor cortex).[22][24][34]

At least three representations of the hand were reported in the motor cortex, one in the primary motor cortex, one in the ventral premotor cortex, and one in the dorsal premotor cortex.[4][22] By implication, at least three different cortical fields may exist, each one performing its own special function in relation to the fingers and wrist.

For these and other reasons, a consensus has now emerged that the lateral motor cortex does not consist of a single, simple map of the body, but instead contains multiple subregions including the primary motor cortex and several premotor fields. These premotor fields have diverse properties. Some project to the spinal cord and may play a direct role in movement control, whereas others do not. Whether these cortical areas are arranged in a hierarchy or share some other more complex relationship is still debated.

Graziano and colleagues suggested an alternative principle of organization for the primary motor cortex and the caudal part of the premotor cortex, all regions that project directly to the spinal cord and that were included in the Penfield and Woolsey definition of M1. In this alternative proposal, the motor cortex is organized as a map of the natural behavioral repertoire.[9][35] The complicated, multifaceted nature of the behavioral repertoire results in a complicated, heterogeneous map in cortex, in which different parts of the movement repertoire are emphasized in different cortical subregions. More complex movements such as reaching or climbing require more coordination among body parts, the processing of more complex control variables, the monitoring of objects in the space near the body, and planning several seconds into the future. Other parts of the movement repertoire, such as manipulating an object with the fingers once the object has been acquired, or manipulating an object in the mouth, involve less planning, less computation of spatial trajectory, and more control of individual joint rotations and muscle forces. In this view the more complex movements, especially multi-segmental movements, come to be emphasized in the more anterior part of the motor map because that cortex emphasizes the musculature of the back and neck which serves as the coordinating link between body parts. In contrast the simpler parts of the movement repertoire that tend to focus more on the distal musculature are emphasized in the more posterior cortex. In this alternative view, though movements of lesser complexity are emphasized in the primary motor cortex and movements of greater complexity are emphasized in the caudal premotor cortex, this difference does not necessarily imply a control hierarchy. Instead the regions differ from each other, and contain subregions with differing properties, because the natural movement repertoire itself is heterogeneous.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Vogt, C. and Vogt, O. (1919). "Ergebnisse unserer Hirnforschung". Journal für Psychologie und Neurologie 25: 277–462.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Vogt, C. and Vogt, O. (1926). "Die vergleichend-architektonische und die vergleichend-reizphysiologische Felderung der Grosshirnrinde unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der menschlichen". Naturwissenschaften 14 (50–51): 1190–1194. doi:10.1007/bf01451766. Bibcode: 1926NW.....14.1190V.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Matelli, M., Luppino, G. and Rizzolati, G (1985). "Patterns of cytochrome oxidase activity in the frontal agranular cortex of the macaque monkey". Behav. Brain Res. 18 (2): 125–136. doi:10.1016/0166-4328(85)90068-3. PMID 3006721.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 He, S.Q., Dum, R.P. and Strick, P.L (1995). "Topographic organization of corticospinal projections from the frontal lobe: motor areas on the medial surface of the hemisphere". J. Neurosci. 15 (5): 3284–3306. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03284.1995. PMID 7538558.

- ↑ Preuss, T.M., Stepniewska, I. and Kaas, J.H (1996). "Movement representation in the dorsal and ventral premotor areas of owl monkeys: a microstimulation study". J. Comp. Neurol. 371 (4): 649–676. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960805)371:4<649::AID-CNE12>3.0.CO;2-E. PMID 8841916.

- ↑ Hochermann, S.; Wise, S.P (1991). "Effects of hand movement path on motor cortical activity in awake, behaving rhesus monkeys". Exp. Brain Res. 83 (2): 285–302. doi:10.1007/bf00231153. PMID 2022240.

- ↑ Cisek, P; Kalaska, J.F (2005). "Neural correlates of reaching decisions in dorsal premotor cortex: specification of multiple direction choices and final selection of action". Neuron 45 (5): 801–814. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.027. PMID 15748854.

- ↑ Churchland, M.M., Yu, B.M., Ryu, S.I., Santhanam, G. and Shenoy, K.V (2006). "Neural variability in premotor cortex provides a signature of motor preparation". J. Neurosci. 26 (14): 3697–3712. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3762-05.2006. PMID 16597724.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Graziano, M.S.A. (2008). The Intelligent Movement Machine. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Weinrich, M., Wise, S.P. and Mauritz, K.H (1984). "A neurophyiological study of the premotor cortex in the rhesus monkey". Brain 107 (2): 385–414. doi:10.1093/brain/107.2.385. PMID 6722510.

- ↑ Brasted, P.J.; Wise, S.P (2004). "Comparison of learning-related neuronal activity in the dorsal premotor cortex and striatum". European Journal of Neuroscience 19 (3): 721–740. doi:10.1111/j.0953-816X.2003.03181.x. PMID 14984423. https://zenodo.org/record/1230597.

- ↑ Muhammad, R., Wallis, J.D. and Miller, E.K (2006). "A comparison of abstract rules in the prefrontal cortex, premotor cortex, inferior temporal cortex, and striatum". J. Cogn. Neurosci. 18 (6): 974–989. doi:10.1162/jocn.2006.18.6.974. PMID 16839304.

- ↑ "Primate frontal eye fields. II. Physiological and anatomical correlates of electrically evoked eye movements". J. Neurophysiol. 54 (3): 714–734. 1985. doi:10.1152/jn.1985.54.3.714. PMID 4045546.

- ↑ Boussaoud D (1985). "Primate premotor cortex: modulation of preparatory neuronal activity by gaze angle". J. Neurophysiol. 73 (2): 886–890. doi:10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.886. PMID 7760145.

- ↑ Rizzolatti, G., Scandolara, C., Matelli, M. and Gentilucci, J (1981). "Afferent properties of periarcuate neurons in macaque monkeys, II. Visual responses". Behav. Brain Res. 2 (2): 147–163. doi:10.1016/0166-4328(81)90053-X. PMID 7248055.

- ↑ Fogassi, L., Gallese, V., Fadiga, L., Luppino, G., Matelli, M. and Rizzolatti, G (1996). "Coding of peripersonal space in inferior premotor cortex (area F4)". J. Neurophysiol. 76 (1): 141–157. doi:10.1152/jn.1996.76.1.141. PMID 8836215.

- ↑ Graziano, M.S.A., Yap, G.S. and Gross, C.G (1994). "Coding of visual space by premotor neurons". Science 266 (5187): 1054–1057. doi:10.1126/science.7973661. PMID 7973661. Bibcode: 1994Sci...266.1054G. http://wexler.free.fr/library/files/graziano%20(1994)%20coding%20of%20visual%20space%20by%20premotor%20neurons.pdf.

- ↑ Graziano, M.S.A., Reiss, L.A. and Gross, C.G (1999). "A neuronal representation of the location of nearby sounds". Nature 397 (6718): 428–430. doi:10.1038/17115. PMID 9989407. Bibcode: 1999Natur.397..428G.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Graziano, M.S.A., Taylor, C.S.R. and Moore, T. (2002). "Complex movements evoked by microstimulation of precentral cortex". Neuron 34 (5): 841–851. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00698-0. PMID 12062029.

- ↑ Cooke, D.F. and Graziano, M.S.A (2004). "Super-flinchers and nerves of steel: Defensive movements altered by chemical manipulation of a cortical motor area". Neuron 43 (4): 585–593. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.029. PMID 15312656.

- ↑ Graziano, M.S.A. and Cooke, D.F. (2006). "Parieto-frontal interactions, personal space, and defensive behavior". Neuropsychologia 44 (6): 845–859. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.09.009. PMID 16277998.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Rizzolatti, G., Camarda, R., Fogassi, L., Gentilucci, M., Luppino, G. and Matelli, M (1988). "Functional organization of inferior area 6 in the macaque monkey. II. Area F5 and the control of distal movements". Exp. Brain Res. 71 (3): 491–507. doi:10.1007/bf00248742. PMID 3416965.

- ↑ Murata, A., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., Gallese, V. Raos, V and Rizzolatti, G (1997). "Object representation in the ventral premotor cortex (area F5) of the monkey". J. Neurophysiol. 78 (4): 2226–22230. doi:10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.2226. PMID 9325390.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 di Pellegrino, G., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., Gallese, V. and Rizzolatti, G (1992). "Understanding motor events: a neurophysiological study". Exp. Brain Res. 91 (1): 176–180. doi:10.1007/bf00230027. PMID 1301372.

- ↑ Rizzolatti, G.; Sinigaglia, C (2010). "The functional role of the parieto-frontal mirror circuit: interpretations and misinterpretations". Nature Reviews Neuroscience 11 (4): 264–274. doi:10.1038/nrn2805. PMID 20216547. https://air.unimi.it/bitstream/2434/147582/2/Rizzolatti%26Sinigaglia2010.pdf.

- ↑ Campbell, A. W. (1905). Histological Studies on the Localization of Cerebral Function. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press. https://archive.org/details/histologicalstud00camp.

- ↑ Brodmann, K (1909). Vergleichende Lokalisationslehre der Grosshirnrinde. Leipzig: J.A. Barth. https://archive.org/details/b28062449.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Fulton, J (1935). "A note on the definition of the "motor" and "premotor" areas". Brain 58 (2): 311–316. doi:10.1093/brain/58.2.311.

- ↑ Penfield, W. and Boldrey, E. (1937). "Somatic motor and sensory representation in the cerebral cortex of man as studied by electrical stimulation". Brain 60 (4): 389–443. doi:10.1093/brain/60.4.389.

- ↑ Woolsey, C.N., Settlage, P.H., Meyer, D.R., Sencer, W., Hamuy, T.P. and Travis, A.M. (1952). "Pattern of localization in precentral and "supplementary" motor areas and their relation to the concept of a premotor area". Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Disease (New York, NY: Raven Press) 30: 238–264.

- ↑ Roland, P.E., Larsen, B., Lassen, N.A. and Skinhoj, E (1980). "Supplementary motor area and other cortical areas in organization of voluntary movements in man". J. Neurophysiol. 43 (1): 118–136. doi:10.1152/jn.1980.43.1.118. PMID 7351547.

- ↑ Roland, P.E., Skinhoj, E., Lassen, N.A. and Larsen, B. (1980). "Different cortical areas in man in organization of voluntary movements in extrapersonal space". J. Neurophysiol. 43 (1): 137–150. doi:10.1152/jn.1980.43.1.137. PMID 7351548.

- ↑ Weinrich, M.; Wise, S.P (1982). "The premotor cortex of the monkey". J. Neurosci. 2 (9): 1329–1345. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.02-09-01329.1982. PMID 7119878.

- ↑ "Functional organization of inferior area 6 in the macaque monkey. I. Somatotopy and the control of proximal movements". Exp. Brain Res. 71 (3): 475–490. 1988. doi:10.1007/bf00248741. PMID 3416964.

- ↑ Graziano, M.S.A. and Aflalo, T.N. (2007). "Mapping behavioral repertoire onto the cortex". Neuron 56 (2): 239–251. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.013. PMID 17964243.

|