Biology:Pythiosis

Pythiosis is a rare and deadly tropical disease caused by the oomycete Pythium insidiosum. Long regarded as being caused by a fungus, the causative agent was not discovered until 1987. It occurs most commonly in horses, dogs, and humans, with isolated cases in other large mammals.[1] The disease is contracted after exposure to stagnant fresh water such as swamps, ponds, lakes, and rice paddies. P. insidiosum is different from other members of the genus in that human and horse hair, skin, and decaying animal and plant tissue are chemoattractants for its zoospores.[2] Additionally, it is the only member in the genus known to infect mammals, while other members are pathogenic to plants and are responsible for some well-known plant diseases.

Epidemiology

Pythiosis occurs in areas with mild winters because the organism survives in standing water that does not reach freezing temperatures.[3] In the United States, it is most commonly found in the Southern Gulf states, especially Louisiana, Florida, and Texas , but has also been reported as far away as California and Wisconsin.[4] It is also found in southeast Asia, eastern Australia , New Zealand, and South America.

Pathophysiology

Pythiosis is suspected to be caused by invasion of the organism into wounds, either in the skin or in the gastrointestinal tract.[3] The disease grows slowly in the stomach and small intestine, eventually forming large lumps of granulation tissue. It can also invade surrounding lymph nodes.

In different animals

The species are listed in decreasing frequency of infection.

Horses

In horses, subcutaneous pythiosis is the most common form and infection occurs through a wound while standing in water containing the pathogen.[2] The disease is also known as leeches, swamp cancer, and bursatti. Lesions are most commonly found on the lower limbs, abdomen, chest, and genitals. They are granulomatous and itchy, and may be ulcerated or fistulated. The lesions often contain yellow, firm masses of dead tissue known as 'kunkers'.[5] It is possible with chronic infection for the disease to spread to underlying bone.[6]

Dogs

Pythiosis of the skin in dogs is rare, and appears as ulcerated lumps. Primary infection can also occur in the bones and lungs. Dogs with the gastrointestinal form of pythiosis have severe thickening of one or more portions of the gastrointestinal tract that may include the stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, or in rare cases, even the esophagus. The resulting pathology results in anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea (sometimes bloody), and abdominal straining. Extensive weight loss may be evident.[7]

Humans

In humans, it can cause arteritis, keratitis, and periorbital cellulitis.[8] This has previously been thought to be a rare disease with only 28 cases reported in the literature up to 1996.[9] However, keratitis due to Pythium may be more common than previously thought, accounting for a proportion of cases that were due to unidentified pathogens.[10] Although this disease was first reported in 1884[11] the species infecting humans - Pythium insidiosum - was only formally recognised in 1987.[12] Diagnosis can be difficult in part because of a lack of awareness of the disease.[13] It does not appear to be transmissible either animal to animal or animal to human. There appear to be three clades of this organism: one in the Americas, a second from Asia and Australia and a third with isolates from Thailand and the USA.[14] The most probable origin of the organism seems to be in Asia.

Most human cases have been reported in Thailand, although cases have been reported elsewhere. In humans, the four forms of the disease are: subcutaneous, disseminated, ocular, and vascular.[15] The ocular form of the disease is the only one known to infect otherwise healthy humans, and has been associated with contact lens use while swimming in infected water. This is also the rarest form with most cases requiring enucleation of the eye.[16] The other forms of the disease require a pre-existing medical condition, usually associated with thalassemic hemoglobinopathy.[15] Prognosis is poor to guarded and treatments include aggressive surgical resection of infected tissue, with amputation suggested if the infection is limited to a distal limb followed by immunotherapy and chemotherapy.[16] A recently published review lists nine cases of vascular pythiosis with five survivors receiving surgery with free margins and all except one requiring amputation. The same review lists nine cases of ocular pythiosis with five patients requiring enucnleation of the infected eye and four patients requiring a corneal transplant.[16]

Cats and other animals

In cats, pythioisis is almost always confined to the skin as hairless and edematous lesions. It is usually found on the limbs, perineum, and at the base of the tail.[17] Lesions may also develop in the nasopharynx.[5] Rabbits are susceptible to pythiosis and are used for in vivo studies of the disease.[citation needed] Other animals reported to have contracted pythiosis are bears, jaguars, camels, and birds, although these have only been singular events.[citation needed]

Diagnosis and treatment

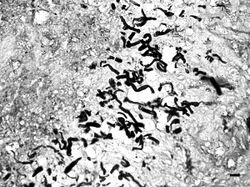

Pythiosis is suspected to be heavily underdiagnosed due to unfamiliarity with the disease, the rapid progression and morbidity, and the difficulty in making a diagnosis. Symptoms often appear once the disease has progressed to the point where treatments are less effective. As the organism is neither a bacterium, virus, nor fungus, routine tests often fail to diagnose it. In cytology and histology, the organism does not stain using Giemsa, H&E, or Diff-Quick, but the hyphae are outlined by surrounding tissue. GMS staining is required to identify the hyphae in slides, and highlights the lack of septation which helps distinguish the organism from fungal hyphae. Granulomatous inflammation with numerous eosinophils is suggestive that the hyphae are oomycetes rather than fungi, which are less likely to attract eosinophils. The symptoms are usually nonspecific and the disease may not be included in a differential diagnosis in human medicine, though it is familiar to veterinarians.

Biopsies of infected tissues are known to be difficult to culture, but can help narrow the diagnosis to several different organisms. A definite diagnosis is confirmed using ELISA testing of serum for pythiosis antibodies, or by PCR testing of infected tissues or cultures.

Due to the poor efficacy of single treatments, pythiosis infections are often treated using a variety of different treatments, all with varying success. Most successful treatments include surgery, immunotherapy, and chemotherapy.[16]

Aggressive surgical resection is the treatment of choice for pythiosis.[18] Because it provides the best opportunity for cure, complete excision of infected tissue should be pursued whenever possible. When cutaneous lesions are limited to a single distal extremity, amputation is often recommended. In animals with gastrointestinal pythiosis, segmental lesions should be resected with 5-cm margins whenever possible. Unfortunately, surgical excision of tissue and amputation do not guarantee complete success and lesions can reappear. So, surgery is often followed by other treatments.[16]

An immunotherapy product derived from antigens of P. insidiosum has been used successfully to treat pythiosis.[19]

Case reports indicate the use of the following chemotherapy treatments with varying success: potassium iodide,[20] amphotericin B,[20] terbinafine,[20][21] itraconazole,[16][21] fluconazole,[16] ketoconazole,[16] natamycin,[16] posaconazole,[16] voriconazole,[16] prednisone,[22] flucytosine,[22] and liposomal nystatin.[22]

References

- ↑ "Hemagglutination Test for Rapid Serodiagnosis of Human Pythiosis". Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16 (7): 1047–51. July 2009. doi:10.1128/CVI.00113-09. PMID 19494087.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Duodenal obstruction caused by infection with Pythium insidiosum in a 12-week-old puppy". J Am Vet Med Assoc 220 (8): 1188–91, 1162. 2002. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.220.1188. PMID 11990966.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Pythiosis of the digestive tract in dogs from Oklahoma". J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 35 (2): 111–4. 1999. doi:10.5326/15473317-35-2-111. PMID 10102178.

- ↑ Gastrointestinal pythiosis in 10 dogs from California. J Vet Intern Med. 2008 Jul-Aug; 22(4):1065-9. Berryessa NA, Marks SL, Pesavento PA, Krasnansky T, Yoshimoto SK, Johnson EG, Grooters AM. Department of Medicine and Epidemiology, University of California, School of Veterinary Medicine, Davis, CA, USA.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Oomycosis". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. http://www.merckvetmanual.com/mvm/index.jsp?cfile=htm/bc/51112.htm.

- ↑ "Pythiosis with bone lesions in a pregnant mare". J Am Vet Med Assoc 216 (11): 1795–8, 1760. 2000. doi:10.2460/javma.2000.216.1795. PMID 10844973.

- ↑ Dr. Susan Muller, DVM. http://www.critterology.com/articles/pythiosis-dog

- ↑ Grooters A (2003). "Pythiosis, lagenidiosis, and zygomycosis in small animals". Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 33 (4): 695–720, v. doi:10.1016/S0195-5616(03)00034-2. PMID 12910739.

- ↑ Thianprasit M, Chaiprasert A, Imwidthaya P (1996). "Human pythiosis". Curr Top Med Mycol 7 (1): 43–54. PMID 9504058.

- ↑ "Pythium insidiosum keratitis: clinical profile and role of DNA sequencing and zoospore formation in diagnosis". Cornea 34 (4): 438–42. 2015. doi:10.1097/ICO.0000000000000349. PMID 25738236.

- ↑ Gaastra W, Lipman LJ, De Cock AW, Exel TK, Pegge RB, Scheurwater J, Vilela R, Mendoza L (2010). "Pythium insidiosum: an overview". Vet Microbiol 146 (1–2): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.07.019. PMID 20800978. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00636632/file/PEER_stage2_10.1016%252Fj.vetmic.2010.07.019.pdf.

- ↑ "Pythium insidiosum sp. nov., the etiologic agent of pythiosis". J Clin Microbiol 25 (2): 344–349. 1987. doi:10.1128/JCM.25.2.344-349.1987. PMID 3818928.

- ↑ Botton SA, Pereira DI, Costa MM, Azevedo MI, Argenta JS, Jesus FP, Alves SH, Santurio JM (2011). "Identification of Pythium insidiosum by nested PCR in cutaneous lesions of Brazilian horses and rabbits". Curr Microbiol 62 (4): 1225–1229. doi:10.1007/s00284-010-9781-4. PMID 21188592.

- ↑ Schurko AM, Mendoza L, Lévesque CA, Désaulniers NL, de Cock AW, Klassen GR (2003). "A molecular phylogeny of Pythium insidiosum". Mycol Res 107 (5): 537–544. doi:10.1017/s0953756203007718. PMID 12884950.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Pan J; Kerkar S.; Siegenthaler M; Hughes M; Pandalai P (2014). "A complicated case of vascular Pythium insidiosum infection treated with limb-sparing surgery". International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 5 (10): 677–680. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.05.018. PMID 25194603.

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 "Treatment outcomes of surgery, antifungal therapy, and immunotherapy in ocular and vascular human pythiosis: a retrospective study of 18 patients". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 70 (6): 1885–1892. 2015. doi:10.1093/jac/dkv008. PMID 25630647.

- ↑ Wolf, Alice (2005). "Opportunistic fungal infections". in August, John R.. Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine Vol. 5. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-0-7216-0423-7.

- ↑ "Diagnosis and treatment of truncal cutaneous pythiosis in a dog". J Am Vet Med Assoc 239 (9): 1232–1235. 2011. doi:10.2460/javma.239.9.1232. PMID 21999797.

- ↑ Grooters AM, Foil CS. Miscellaneous fungal infections. In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 4th ed. Elsevier Saunders, St. Louis, MO, 2012; 675-688.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "Vascular pythiosis in a thalassemic patient". Vascular 17 (4): 234–8. 2009. doi:10.2310/6670.2008.00073. PMID 19698307. http://www.bcdecker.com/pubMedLinkOut.aspx?pub=VASO&vol=17&iss=4&page=234.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Grooters AM. Pythiosis and Lagenidiosis. In: Bonagura, ed. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XIV. Saunders Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2008; 1268-1271.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "Canine gastrointestinal pythiosis treatment by combined antifungal and immunotherapy and review of published studies". Mycopathologia 176 (3–4): 309–315. 2013. doi:10.1007/s11046-013-9683-7. PMID 23918089.

|