Biology:Salmonidae

Salmonidae (/sælˈmɒnɪdiː/, lit. salmon-like) is a family of ray-finned fish, the only extant member of the suborder Salmonoidei[1], consisting of 11 extant genera and over 200 species collectively known as "salmonids" or "salmonoids". The family includes salmon (both Atlantic and Pacific species), trout (both ocean-going and landlocked), char, graylings, freshwater whitefishes, taimens and lenoks, all coldwater mid-level predatory fish that inhabit the subarctic and cool temperate waters of the Northern Hemisphere. The Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), whose Latin name became that of its genus Salmo, is also the eponym of the family and order names.

Salmonids have a relatively primitive appearance among teleost fish, with the pelvic fins being placed far back, and an adipose fin towards the rear of the back. They have slender bodies with rounded scales and forked tail fins, and their mouths contain a single row of sharp teeth.[2] Although the smallest salmonid species is just 13 cm (5.1 in) long for adults, most salmonids are much larger, with the largest reaching 2 m (6 ft 7 in).[3]

All salmonids are migratory fish that spawn in the shallow gravel beds of freshwater headstreams, spend the growing juvenile years in rivers, creeks, small lakes and wetlands, but migrate downstream upon maturity and spend most of their adult lives at much larger waterbodies. Many salmonid species are euryhaline and migrate to the sea or brackish estuaries as soon as they approach adulthood, returning to the upper streams only to reproduce. Such sea-run life cycle is described as anadromous, and other freshwater salmonids that migrate purely between lakes and rivers are considered potamodromous. Salmonids are carnivorous predators of the middle food chain, feeding on smaller fish, crustaceans, aquatic insects and larvae, tadpoles and sometimes fish eggs (even those of their own kind),[2] and in turn being preyed upon by larger predators. Many species of salmonids are thus considered keystone organisms important for both freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems due to the biomass transfer provided by their mass migration from oceanic to inland waterbodies.

Evolution

Current salmonids comprise three main clades taxonomically treated as subfamilies: Coregoninae (freshwater whitefishes), Thymallinae (graylings), and Salmoninae (trout, salmon, char, taimens and lenoks). Generally, all three lineages are accepted to allocate a suite of derived traits indicating a monophyletic group.[1][4]

The suborder Salmonoidei, containing only Salmonidae, is one of two extant clades within the order Salmoniformes, which first appeared during the Santonian and Campanian stages of the Late Cretaceous.[5][6] The other is the Esocoidei, which contains the pikes and mudminnows.[1] Formerly, many more families were included within this group, but all have since been reclassified into their own orders. During the early 21st century, Salmoniformes was redefined to include only Salmonidae as a monotypic order.[7] However, as recent phylogenetic studies have affirmed the relationship between the Salmonoidei and Esocoidei, the latter have returned to being considered a suborder of Salmoniformes.[1][8]

Klondike Mountain Formation

It is thought that salmon and pike diverged from one another during the Cretaceous, but until 2025, there was no fossil evidence of salmonids occurring during this time period. In 2025, the earliest known fossil salmonid, Sivulliusalmo alaskensis, was described from the early Maastrichtian-aged Prince Creek Formation of Alaska, with indeterminate remains of this genus also being identified from the older Campanian-aged Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta. The occurrence of Sivulliusalmo in these northern habitats suggests that the modern salmonid preference for cool, high-latitude waters is an ancient, conserved trait.[9]

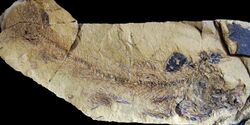

Prior to the description of Sivulliusalmo, the earliest record of salmonids was the Early Eocene-aged[10] Eosalmo driftwoodensis, a stem-salmonine, which was first described from fossils found at Driftwood Creek, central British Columbia,[11] and has been recovered from most sites in the Eocene Okanagan Highlands.[12][13][14] This genus shares traits found in all three subfamily lineages. Hence, E. driftwoodensis is an archaic salmonid, representing an important stage in salmonid evolution.[4] Fossil scales of coregonines are known from the Late Eocene or Early Oligocene of California.[15]

A gap appears in the salmonine fossil record after E. driftwoodensis until about 7 million years ago (mya), in the Late Miocene, when trout-like fossils appear in Idaho, in the Clarkia Lake beds.[16] Several of these species appear to be Oncorhynchus — the current genus for Pacific salmon and Pacific trout. The presence of these species so far inland established that Oncorhynchus was not only present in the Pacific drainages before the beginning of the Pliocene (~5–6 mya), but also that rainbow and cutthroat trout, and Pacific salmon lineages had diverged before the beginning of the Pliocene. Consequently, the split between Oncorhynchus and Salmo (Atlantic salmon and European trout) must have occurred well before the Pliocene. Suggestions have gone back as far as the Early Miocene (about 20 mya).[4][17]

Genetics

Based on the most current evidence, salmonids diverged from the rest of teleost fish no later than 88 million years ago, during the late Cretaceous. This divergence was marked by a whole-genome duplication event in the ancestral salmonid, where the diploid ancestor became tetraploid.[18][19] This duplication is the fourth of its kind to happen in the evolutionary lineage of the salmonids, with two having occurred commonly to all bony vertebrates, and another specifically in the teleost fishes.[19]

Extant salmonids all show evidence of partial tetraploidy, as studies show the genome has undergone selection to regain a diploid state. Work done in the rainbow trout (Onchorhynchus mykiss) has shown that the genome is still partially-tetraploid. Around half of the duplicated protein-coding genes have been deleted, but all apparent miRNA sequences still show full duplication, with potential to influence regulation of the rainbow trout's genome. This pattern of partial tetraploidy is thought to be reflected in the rest of extant salmonids.[20]

The earliest presumed crown-group salmonid fish (E. driftwoodensis) does not appear until the middle Eocene.[21] This fossil already displays traits associated with extant salmonids, but as the genome of E. driftwoodensis cannot be sequenced, it cannot be confirmed if polyploidy was present in this animal at this point in time.

Given a lack of earlier transition fossils, and the inability to extract genomic data from specimens other than extant species, the dating of the whole-genome duplication event in salmonids was historically a very broad categorization of times, ranging from 25 to 100 million years in age.[20] New advances in calibrated relaxed molecular clock analyses have allowed for a closer examination of the salmonid genome, and has allowed for a more precise dating of the whole-genome duplication of the group, that places the latest possible date for the event at 88 million years ago.[19]

This more precise dating and examination of the salmonid whole-genome duplication event has allowed more speculation on the radiation of species within the group. Historically, the whole-genome duplication event was thought to be the reason for the variation within Salmonidae. Current evidence done with molecular clock analyses revealed that much of the speciation of the group occurred during periods of intense climate change associated with the last ice ages, with especially high speciation rates being observed in salmonids that developed an anadromous lifestyle.[19]

Classification

Together with the closely related orders Esociformes (pikes and mudminnows), Osmeriformes (true smelts) and Argentiniformes (marine smelts and barreleyes), Salmoniformes comprise the superorder Protacanthopterygii.

The only extant family within Salmoniformes, Salmonidae, is divided into three subfamilies and around 10 genera containing about 220 species. The concepts of the number of species recognised vary among researchers and authorities; the numbers presented below represent the higher estimates of diversity:[3]

| Phylogeny of Salmonidae[22][23] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Order Salmoniformes

- Family: Salmonidae

- †Sivulliusalmo Brinkman et al., 2025 (1 species, Late Cretaceous)[9]

- Subfamily: Coregoninae

- Subfamily: Thymallinae

- Subfamily: Salmoninae

- †Eosalmo Wilson, 1977 (1 species, Eocene)

- †Paleolox Kimmel, 1975 (1 species, Late Miocene)[24][25]

- Tribe: Salmonini

- Salmo Linnaeus, 1758 - Atlantic salmon and trout (47 species)

- Salvelinus Richardson, 1836 - Char and trout (e.g. brook trout, lake trout) (51 species)

- Salvethymus Chereshnev & Skopets, 1990 - Long-finned char (1 species)

- Tribe: Oncorhynchini

- Brachymystax Günther, 1866 - lenoks (4 species)

- Hucho Günther, 1866 - taimens (4 species)

- Oncorhynchus Suckley, 1861 - Pacific salmon and trout (12 species)

- Parahucho Vladykov, 1963 - Sakhalin taimen (1 species)

Hybrid crossbreeding

The following table shows results of hybrid crossbreeding combination in Salmonidae.[26]

| Crossbreeding | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| male | |||||||||||||

| Salvelinus | Oncorhynchus | Salmo | |||||||||||

| leucomaenis (white-spotted char) |

fontinalis (Brook trout) |

mykiss (Rainbow trout) |

masou masou (masu salmon) |

masou ishikawae (Amago Salmon) |

gorbuscha (pink salmon) |

nerka (Sockeye salmon) |

keta (chum salmon) |

kisutsh (coho salmon) |

tshawytscha (chinook salmon) |

trutta (Brown trout) |

salar (Atlantic Salmon) | ||

| female | |||||||||||||

| (Salvelinus) | leucomaenis (white-spotted char) |

- | O | X | O | O | X | X | O | ||||

| fontinalis (Brook trout) |

O | - | X | O | O | X | X | O | X | X | |||

| (Oncorhynchus) | mykiss (Rainbow trout) |

O | O | - | O | O | O | X | X | X | X | X | |

| masou masou (masu salmon) |

O | X | X | - | O | X | X | O | O | X | |||

| masou ishikawae (Amago Salmon) |

O | O | X | O | - | X | O | ||||||

| gorbuscha (pink salmon) |

X | - | O | O | O | ||||||||

| nerka (Sockeye salmon) |

X | X | X | X | X | O | - | O | O | O | X | ||

| keta (chum salmon) |

X | X | X | X | O | O | - | O | X | X | |||

| kisutsh (coho salmon) |

X | X | O | O | X | - | O | X | X | ||||

| tshawytscha (chinook salmon) |

O | O | O | X | O | - | |||||||

| Salmo | trutta (Brown trout) |

O | O | X | O | O | X | X | - | O | |||

| salar (Atlantic Salmon) |

O | X | X | X | O | - | |||||||

note :- : The identical kind, O : (survivability), X : (Fatality)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Fricke, R.; Eschmeyer, W. N.; Van der Laan, R. (2025). "ESCHMEYER'S CATALOG OF FISHES: CLASSIFICATION" (in en). https://www.calacademy.org/eschmeyers-catalog-of-fishes-classification.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 McDowell, Robert M. (1998). Paxton, J.R.. ed. Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 114–116. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2008). "Salmonidae" in FishBase. December 2008 version.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 McPhail, J.D.; Strouder, D.J. (1997). "Pacific Salmon and Their Ecosystems: Status and Future Options". The Origin and Speciation of Oncorhynchus. New York, New York: Chapman & Hall.

- ↑ Szabó, Márton; Ősi, Attila (September 2017). "The continental fish fauna of the Late Cretaceous (Santonian) Iharkút locality (Bakony Mountains, Hungary)". Central European Geology 60 (2): 230–287. doi:10.1556/24.60.2017.009. ISSN 1788-2281. Bibcode: 2017CEJGl..60..230S.

- ↑ Brinkman, Donald B.; Newbrey, Michael G.; Neuman, Andrew G.; Eaton, Jeffrey G. (2013). "Freshwater Osteichthyes from the Cenomanian to Late Campanian of Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument, Utah". in Titus, Alan L.. At the Top of the Grand Staircase: The Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 195–236. ISBN 978-0-253-00896-1. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289813917.

- ↑ J. S. Nelson; T. C. Grande; M. V. H. Wilson (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). Wiley. p. 348. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6. https://sites.google.com/site/fotw5th/. Retrieved 2019-02-23.

- ↑ Near, Thomas J; Thacker, Christine E (18 April 2024). "Phylogenetic classification of living and fossil ray-finned fishes (Actinopterygii)". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History 65: 101. doi:10.3374/014.065.0101. Bibcode: 2024BPMNH..65..101N.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Brinkman, Donald B.; López, J. Andrés; Erickson, Gregory M.; Eberle, Jaelyn J.; Muñoz, Xochitl; Wilson, Lauren N.; Perry, Zackary R.; Murray, Alison M. et al. (2025). "Fishes from the Upper Cretaceous Prince Creek Formation, North Slope of Alaska, and their palaeobiogeographical significance" (in en). Papers in Palaeontology 11 (3). doi:10.1002/spp2.70014. ISSN 2056-2802. Bibcode: 2025PPal...1170014B.

- ↑ Eberle, Jaelyn J.; Rybczynski, Natalia; Greenwood, David R. (2014-06-07). "Early Eocene mammals from the Driftwood Creek beds, Driftwood Canyon Provincial Park, northern British Columbia" (in en). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34 (4): 739–746. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.838175. ISSN 0272-4634. Bibcode: 2014JVPal..34..739E. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02724634.2014.838175.

- ↑ Campbell, Matthew A.; López, J. Andrés; Sado, Tetsuya; Miya, Masaki (2013). "Pike and salmon as sister taxa: Detailed intraclade resolution and divergence time estimation of Esociformes + Salmoniformes based on whole mitochondrial genome sequences". Gene 530 (1): 57–65. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2013.07.068. ISSN 0378-1119. PMID 23954876.

- ↑ Wilson, M.V. (1977). "Middle Eocene freshwater fishes from British Columbia". Life Sciences Contributions, Royal Ontario Museum 113: 1–66.

- ↑ Wilson, M.V.H.; Li, Guo-Qing (1999). "Osteology and systematic position of the Eocene salmonid †Eosalmo driftwoodensis Wilson from western North America". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 99 (125): 279–311. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1999.tb00594.x. http://www.lifesci.ucsb.edu/eemb/labs/oakley/research/WilsonLi.pdf. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ↑ Wilson, M.V.H. 2009. McAbee Fossil Site Assessment Report. 60 pp.Online PDF. Accessed 17 May 2021.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 David, Lorre R. (1946). "Some Typical Upper Eogene Fish Scales from California". Contributions to Paleontology IV. https://authors.library.caltech.edu/records/v03cm-86s21.

- ↑ Smiley, Charles J. "Late Cenozoic History of the Pacific Northwest" (PDF). Association for the Advancement of Science: Pacific Division. http://www.sou.edu/aaaspd/TableContents/LateCenHist.pdf/.

- ↑ Montgomery, David R. (2000). "Coevolution of the Pacific Salmon and Pacific Rim Topography" (PDF). Department of Geological Sciences, University of Washington. http://duff.ess.washington.edu/grg/publications/pdfs/salmonevolution.pdf/.

- ↑ Allendorf, Fred W.; Thorgaard, Gary H. (1984). "Tetraploidy and the Evolution of Salmonid Fishes". Evolutionary Genetics of Fishes. pp. 1–53. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-4652-4_1. ISBN 978-1-4684-4654-8.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 MacQueen, D. J.; Johnston, I. A. (2014). "A well-constrained estimate for the timing of the salmonid whole genome duplication reveals major decoupling from species diversification". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281 (1778). doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2881. PMID 24452024.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Berthelot, Camille; Brunet, Frédéric; Chalopin, Domitille; Juanchich, Amélie; Bernard, Maria; Noël, Benjamin; Bento, Pascal; Da Silva, Corinne et al. (2014). "The rainbow trout genome provides novel insights into evolution after whole-genome duplication in vertebrates". Nature Communications 5. doi:10.1038/ncomms4657. PMID 24755649. Bibcode: 2014NatCo...5.3657B.

- ↑ Zhivotovsky, L. A. (2015). "Genetic history of salmonid fishes of the genus Oncorhynchus". Russian Journal of Genetics 51 (5): 491–505. doi:10.1134/s1022795415050105. PMID 26137638.

- ↑ Crête-Lafrenière, Alexis; Weir, Laura K.; Bernatchez, Louis (2012). "Framing the Salmonidae Family Phylogenetic Portrait: A More Complete Picture from Increased Taxon Sampling". PLOS ONE 7 (10). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046662. PMID 23071608. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...746662C.

- ↑ Shedko, S. V.; Miroshnichenko, I. L.; Nemkova, G. A. (2013). "Phylogeny of salmonids (salmoniformes: Salmonidae) and its molecular dating: Analysis of mtDNA data". Russian Journal of Genetics 49 (6): 623–637. doi:10.1134/S1022795413060112. PMID 24450195.

- ↑ Smith, Gerald R.; Kimmel, P. G. (1975). "Fishes of the Pliocene Glenns Ferry Formation, Southwest Idaho; Fishes of the Miocene - Pliocene Deer Butte Formation, Southeast Oregon Claude W. Hibbard Memorial Volume V" (in en-US). Papers on Paleontology (14): 1–87. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/48614.

- ↑ Stearley, Ralph F.; Smith, Gerald R. (2016-10-14). "FISHES OF THE MIO-PLIOCENE WESTERN SNAKE RIVER PLAIN AND VICINITY" (in en-US). Miscellaneous Publications Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 204 (1). ISSN 0076-8405. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/134040.

- ↑ Ito, Daisuke; Fujiwara, Atushi; Abe, Syuiti (2006). "Hybrid Inviability and Chromosome Abnormality in Salmonid Fish". The Journal of Animal Genetics 34: 65–70. doi:10.5924/abgri2000.34.65.

Further reading

- Behnke, Robert J. Trout and Salmon of North America, Illustrated by Joseph R. Tomelleri. 1st Chanticleer Press ed. New York: The Free Press, 2002. ISBN 0-7432-2220-2

- Dushkina, L.A. (January 1994). "Farming of Salmonids in Russia". Aquaculture Research 25 (1): 121–126. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2109.1994.tb00672.x.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2004). "Salmonidae" in FishBase. October 2004 version.

- "Salmonidae". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=161931.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2004). "Salmoniformes" in FishBase. October 2004 version.

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology 364: 560. http://strata.ummp.lsa.umich.edu/jack/showgenera.php?taxon=611&rank=class. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

Template:Actinopterygii Template:Salmon Wikidata ☰ Q184238 entry

|