Biology:Seppo koponeni

| Seppo koponeni | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype and only known specimen MB.A 2966. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Missing taxonomy template (fix): | Incertae sedis/Palpimanoidea |

| Genus: | †Seppo Selden & Dunlop, 2014 |

| Species: | †S. koponeni

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Seppo koponeni Selden & Dunlop, 2014

| |

Seppo is an extinct genus of spiders, possibly of the superfamily Palpimanoidea, that lived about 180 million years ago, in the Early Jurassic (Lower Toarcian) of what is now Europe. The sole species Seppo koponeni is known from a single fossil from Grimmen, Germany.[1] With the scorpion Liassoscorpionides, it is one of the two only known arachnids from the Lower Jurassic of Germany .[1] Seppo is the first unequivocal Early Jurassic spider, and was recovered from the Green Series member of the Toarcian Ciechocinek Formation.[1]

Description

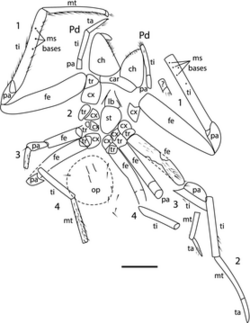

The spider was described from a single female specimen. It is unknown if was an adult.[1] The carapace is unknown, and besides that has preserved bowed converging sides with a curved posterior margin with straight posterior border of the labium, with row of at least 12 peg teeth along the cheliceral furrow, no true teeth, scattered setae on anterior surface, and slender pedipalps.[1] Legs are preserved, the first and second being much longer than the third and fourth. All are well covered in setae and bristles, especially on the tibiae and metatarsi of leg I.[1] It most likely belongs to the Palpimanoidea, based on the presence of cheliceral peg teeth.[1]

Discovery

The single known specimen was found on locality known for its fossil insects in Grimmen, near Greifswald, at the north of Germany .[1] It was reported in 2003, when Ansorge did a recompilation of insect taxa on the Toarcian strata of Germany and England .[2] The specimen was recovered from the Falciferum zone (Exaratum subzone), c. 180 Ma, and presented as "Araneae gen. et sp. nov." (Chelicerata).[2] It was recovered from a fragment of calcareous nodule from the grey-green claystone, recovered from the closed since the 90's clay pit of Klein Lehmhagen, near Grimmen, Western Pomerania, Germany.[2][1] It is curious for being one of the rare few examples of spiders found on calcium carbonate (along with others from the Eocene limestone of the Isle of Wight, England [3]). The specimen was found with some parts preserved as external moulds, and these show setation and spination. This is an exception, since most of the specimen is an internal mould of calcium carbonate.[1] The specimen was labeled with the number MB.A 2966, and deposited in the Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, being named in 2014 by Paul A. Selden & Jason A. Dunlop Seppo koponeni, after the Finnish arachnologist Seppo Koponen, to celebrate his 70th birthday.[1][4]

Phylogeny

The genus was described as the oldest Palpimanoidea or the nearest sister taxon to the group.[5] The exact familiar placement of the genus is unclear, as it was assigned to the family based on the presence of peg teeth, a synapomorphy thought to be unique to the superfamily.[5] However, recent revisions of modern spiders have shown that this character is also present in the Mimetidae and other Entelegynae families.[5] Early araneomorphs such as those in the clade Synspermiata and the families Filistatidae, Austrochilidae and Leptonetidae lack it, locating the genus as either a stem Palpimanoidea or a stem Entelegynae.[5]

Ecology

Seppo koponeni is one of the only two arachnids ever to have been found in the Toarcian rocks of north Germany, outnumbered by several thousand insect specimens at several localities.[6][1] The different between the number of insects as opposed to arachnids has not been studied in depth. A possibility is that because insects can fly over water, they fall into it far more easily than spiders.[1] It is unclear how the spider ended on a marine clay deposit, far from the land, although several theories have been suggested: ballooning is a possibility as a method of transport, perhaps helped by severe storms, hurricanes, and tornadoes.[1] Another possibility might be that it was carried out to sea on floating vegetation, as wood remains have been recovered in the deposit.[1]

On nearby land, ground dwellers were represented by arachnids, such as Seppo and scorpions, but also by Gryllidae, such as Protogryllus dobbertinensis, grylloblattodeans such as Nele jurassica, and dermapterans.[2] These arthropods never moved far from where they lived and are generally very rare in the rocks.[2] Seppo shows a rather unusual morphology, with large and porrect chelicerae and a robust leg I, contrasted with a short leg III.[1] The robust and well-armed first legs, directed forwards, give the impression that they were prey capture appendages, a morphology typical of a sit-and-wait predator, while the short third legs are more typical of web spiders, especially orbweavers, but also palpimanoids. Short third legs are not usually found on spiders that are substrate dwellers, which have more equal legs.[1] Seppo was probably not a habitual ground dweller. The armoured front legs related to capturing dangerous prey are typical of many extant palpimanoids that are araneophagous.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 Selden, Paul A.; Dunlop, Jason A. (2014). "The first fossil spider (Araneae: Palpimanoidea) from the Lower Jurassic (Grimmen, Germany)". Zootaxa 3894 (1): 161–168. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3894.1.13. PMID 25544628. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270292420. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Ansorge, J. (2003). "Insects from the Lower Toarcian of Middle Europe and England". Proceedings of the Second Palaeoentomological Congress, Acta Zoologica Cracoviensia 46 (1): 291–310. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271444424. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ↑ Selden, P.A. (2001). "Eocene spiders from the Isle of Wight with preserved respiratory structures". Palaeontology 44 (1): 695–729. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00199. https://www.palass.org/publications/palaeontology-journal/archive/44/4/article_pp695-729. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ Marusik, Y.; Fet, V. (2014). "Honouring Seppo Koponen on the occasion of this 70th Birthday". Zootaxa 3894 (1): 5–9. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3894.1.3. PMID 25544618. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25544618/. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Magalhaes, I. L.; Azevedo, G. H.; Michalik, P; Ramírez, M. J. (2020). "The fossil record of spiders revisited: implications for calibrating trees and evidence for a major faunal turnover since the Mesozoic". Biological Reviews 95 (1): 184–217. doi:10.1111/brv.12559. PMID 31713947. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/brv.12559?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=pmd_7tCn4jok7zqphWFQ1Vd.bGop4eJBgjOO2RZNrjlQQ0Y-1635288550-0-gqNtZGzNAiWjcnBszQzR. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ↑ Ansorge, J. (2007). "Liastongrube Grimmen". Biuletyn Państwowego Instytutu Geologicznego 424 (1): 37–41. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285166668. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

Wikidata ☰ {{{from}}} entry

|