Biology:Timeline of ankylosaur research

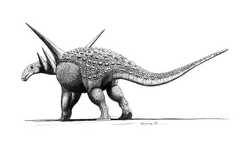

This timeline of ankylosaur research is a chronological listing of events in the history of paleontology focused on the ankylosaurs, quadrupedal herbivorous dinosaurs who were protected by a covering bony plates and spikes and sometimes by a clubbed tail. Although formally trained scientists did not begin documenting ankylosaur fossils until the early 19th century, Native Americans had a long history of contact with these remains, which were generally interpreted through a mythological lens. The Delaware people have stories about smoking the bones of ancient monsters in a magic ritual to have wishes granted and ankylosaur fossils are among the local fossils that may have been used like this.[1] The Native Americans of the modern southwestern United States tell stories about an armored monster named Yeitso that may have been influenced by local ankylosaur fossils.[2] Likewise, ankylosaur remains are among the dinosaur bones found along the Red Deer River of Alberta, Canada where the Piegan people believe that the Grandfather of the Buffalo once lived.[3]

The first scientifically documented ankylosaur remains were recovered from Early Cretaceous rocks in England and named Hylaeosaurus armatus by Gideon Mantell in 1833.[4] However, the Ankylosauria itself would not be named until Henry Fairfield Osborn did so in 1923 nearly a hundred years later.[5] Prior to this, the ankylosaurs had been considered members of the Stegosauria, which included all armored dinosaurs when Othniel Charles Marsh named the group in 1877. It was not until 1927 that Alfred Sherwood Romer implemented the modern use of the name Stegosauria as specifically pertaining to the plate-backed and spike-tailed dinosaurs of the Jurassic that form the ankylosaurs' nearest relatives.[6] The next major revision to ankylosaur taxonomy would not come until Walter Coombs divided the group into the two main families paleontologists still recognize today; the nodosaurids and ankylosaurids.[5] Since then, many new ankylosaur genera and species have been discovered from all over the world and continue to come to light. Many fossil ankylosaur trackways have also been recognized.[7] <timeline> ImageSize = width:1250px height:auto barincrement:15px PlotArea = left:10px bottom:50px top:10px right:10px Period = from:1830 till:2050 TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:50 start:1850 ScaleMinor = unit:year increment:10 start:1830 TimeAxis = orientation:hor AlignBars = justify Colors =

#legends id:1700s value:rgb(0.5,0.78,0.31) id:1700syears value:rgb(0.63,0.78,0.65) id:1800s value:rgb(0.999999,0.9,0.1) id:1800syears value:rgb(0.95,0.98,0.11) id:1900s value:rgb(0.94,0.25,0.24) id:1900syears value:rgb(0.95,0.56,0.45) id:2000s value:rgb(0.2,0.7,0.79) id:2000syears value:rgb(0.52,0.81,0.91)

BarData=

bar:eratop bar:space bar:periodtop bar:space bar:NAM1 bar:NAM2 bar:NAM3 bar:NAM4 bar:NAM5 bar:NAM6 bar:NAM7 bar:NAM8 bar:NAM9 bar:NAM10 bar:NAM11 bar:NAM12 bar:NAM13 bar:NAM14 bar:NAM15 bar:NAM16 bar:NAM17 bar:NAM18 bar:NAM19 bar:NAM20 bar:NAM21 bar:NAM22 bar:NAM23 bar:NAM24 bar:NAM25 bar:NAM26 bar:NAM27 bar:NAM28 bar:NAM29 bar:NAM30 bar:NAM31 bar:NAM32 bar:NAM33 bar:NAM34 bar:NAM35 bar:NAM36 bar:NAM37 bar:space bar:period bar:space bar:era

PlotData=

align:center textcolor:black fontsize:M mark:(line,black) width:25 shift:(7,-4) bar:periodtop from:1830 till:1840 color:1800syears text:30s from:1840 till:1850 color:1800syears text:40s from:1850 till:1860 color:1800syears text:50s from:1860 till:1870 color:1800syears text:60s from:1870 till:1880 color:1800syears text:70s from:1880 till:1890 color:1800syears text:80s from:1890 till:1900 color:1800syears text:90s from:1900 till:1910 color:1900syears text:00s from:1910 till:1920 color:1900syears text:10s from:1920 till:1930 color:1900syears text:20s from:1930 till:1940 color:1900syears text:30s from:1940 till:1950 color:1900syears text:40s from:1950 till:1960 color:1900syears text:50s from:1960 till:1970 color:1900syears text:60s from:1970 till:1980 color:1900syears text:70s from:1980 till:1990 color:1900syears text:80s from:1990 till:2000 color:1900syears text:90s from:2000 till:2010 color:2000syears text:00s from:2010 till:2020 color:2000syears text:10s from:2020 till:2030 color:2000syears text:20s from:2030 till:2040 color:2000syears text:30s from:2040 till:2050 color:2000syears text:40s bar:eratop from:1830 till:1900 color:1800s text:19th from:1900 till:2000 color:1900s text:20th from:2000 till:2050 color:2000s text:21st

PlotData=

align:left fontsize:M mark:(line,white) width:5 anchor:till align:left color:1700s bar:NAM1 at:1833 mark:(line,black) text:Hylaeosaurus color:1700s bar:NAM2 at:1856 mark:(line,black) text:Palaeoscincus color:1700s bar:NAM3 at:1867 mark:(line,black) text:Polacanthus color:1700s bar:NAM4 at:1867 mark:(line,black) text:Acanthopholis color:1700s bar:NAM5 at:1869 mark:(line,black) text:Cryptosaurus color:1700s bar:NAM6 at:1871 mark:(line,black) text:Struthiosaurus color:1700s bar:NAM7 at:1871 mark:(line,black) text:Danubiosaurus color:1700s bar:NAM8 at:1875 mark:(line,black) text:Priodontognathus color:1700s bar:NAM9 at:1879 mark:(line,black) text:Anoplosaurus color:1700s bar:NAM10 at:1879 mark:(line,black) text:Eucercosaurus color:1700s bar:NAM11 at:1879 mark:(line,black) text:Syngonosaurus color:1700s bar:NAM12 at:1881 mark:(line,black) text:Crataeomus color:1700s bar:NAM13 at:1881 mark:(line,black) text:Hoplosaurus color:1700s bar:NAM14 at:1881 mark:(line,black) text:Pleuropeltis color:1700s bar:NAM15 at:1881 mark:(line,black) text:Rhadinosaurus color:1700s bar:NAM16 at:1888 mark:(line,black) text:Priconodon color:1700s bar:NAM17 at:1889 mark:(line,black) text:Nodosaurus color:1700s bar:NAM18 at:1893 mark:(line,black) text:Sarcolestes color:1800s bar:NAM19 at:1902 mark:(line,black) text:Euoplocephalus color:1800s bar:NAM20 at:1902 mark:(line,black) text:Hoplitosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM21 at:1902 mark:(line,black) text:Onychosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM22 at:1905 mark:(line,black) text:Stegopelta color:1800s bar:NAM23 at:1908 mark:(line,black) text:Ankylosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM24 at:1909 mark:(line,black) text:Hierosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM25 at:1918 mark:(line,black) text:Leipsanosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM26 at:1919 mark:(line,black) text:Panoplosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM27 at:1924 mark:(line,black) text:Dyoplosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM28 at:1928 mark:(line,black) text:Edmontonia color:1800s bar:NAM29 at:1928 mark:(line,black) text:Scolosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM30 at:1929 mark:(line,black) text:Anodontosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM31 at:1929 mark:(line,black) text:Polacanthoides color:1800s bar:NAM32 at:1929 mark:(line,black) text:Rhodanosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM33 at:1933 mark:(line,black) text:Pinacosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM34 at:1934 mark:(line,black) text:Brachypodosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM1 at:1952 mark:(line,black) text:Syrmosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM2 at:1952 mark:(line,black) text:Talarusus color:1800s bar:NAM3 at:1953 mark:(line,black) text:Peishanosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM4 at:1953 mark:(line,black) text:Sauroplites color:1800s bar:NAM5 at:1953 mark:(line,black) text:Stegosaurides color:1800s bar:NAM6 at:1960 mark:(line,black) text:Silvisaurus color:1800s bar:NAM7 at:1970 mark:(line,black) text:Sauropelta color:1800s bar:NAM8 at:1977 mark:(line,black) text:Tarchia color:1800s bar:NAM9 at:1977 mark:(line,black) text:Saichania color:1800s bar:NAM10 at:1978 mark:(line,black) text:Amtosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM11 at:1980 mark:(line,black) text:Dracopelta color:1800s bar:NAM12 at:1980 mark:(line,black) text:Minmi color:1800s bar:NAM13 at:1982 mark:(line,black) text:Vectensia color:1800s bar:NAM14 at:1983 mark:(line,black) text:Shamosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM15 at:1987 mark:(line,black) text:Maleevus color:1800s bar:NAM16 at:1988 mark:(line,black) text:Denversaurus color:1800s bar:NAM17 at:1993 mark:(line,black) text:Tsagantegia color:1800s bar:NAM18 at:1993 mark:(line,black) text:Tianchisaurus color:1800s bar:NAM19 at:1994 mark:(line,black) text:Mymoorapelta color:1800s bar:NAM20 at:1995 mark:(line,black) text:Niobrarasaurus color:1800s bar:NAM21 at:1995 mark:(line,black) text:Texasetes color:1800s bar:NAM22 at:1996 mark:(line,black) text:Pawpawsaurus color:1800s bar:NAM23 at:1998 mark:(line,black) text:Gargoyleosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM24 at:1998 mark:(line,black) text:Gastonia color:1800s bar:NAM25 at:1998 mark:(line,black) text:Tianzhenosaurus color:1800s bar:NAM26 at:1998 mark:(line,black) text:Shanzia color:1800s bar:NAM27 at:1999 mark:(line,black) text:Animantarx color:1800s bar:NAM28 at:1999 mark:(line,black) text:Nodocephalosaurus color:1900s bar:NAM29 at:2000 mark:(line,black) text:Glyptodontopelta color:1900s bar:NAM30 at:2001 mark:(line,black) text:Aletopelta color:1900s bar:NAM31 at:2001 mark:(line,black) text:Gobisaurus color:1900s bar:NAM32 at:2001 mark:(line,black) text:Liaoningosaurus color:1900s bar:NAM33 at:2001 mark:(line,black) text:Cedarpelta color:1900s bar:NAM34 at:2002 mark:(line,black) text:Crichtonsaurus color:1900s bar:NAM35 at:2002 mark:(line,black) text:Amtosaurus color:1900s bar:NAM36 at:2004 mark:(line,black) text:Bissektipelta color:1900s bar:NAM37 at:2005 mark:(line,black) text:Hungarosaurus color:1900s bar:NAM1 at:2006 mark:(line,black) text:Antarctopelta color:1900s bar:NAM2 at:2007 mark:(line,black) text:Zhejiangosaurus color:1900s bar:NAM3 at:2007 mark:(line,black) text:Zhongyuansaurus color:1900s bar:NAM4 at:2008 mark:(line,black) text:Peloroplites color:1900s bar:NAM5 at:2009 mark:(line,black) text:Minotaurasaurus color:1900s bar:NAM6 at:2009 mark:(line,black) text:Tatankacephalus color:1900s bar:NAM7 at:2011 mark:(line,black) text:Ahshislepelta color:1900s bar:NAM8 at:2011 mark:(line,black) text:Propanoplosaurus color:1900s bar:NAM9 at:2013 mark:(line,black) text:Dongyangopelta color:1900s bar:NAM10 at:2013 mark:(line,black) text:Europelta color:1900s bar:NAM11 at:2013 mark:(line,black) text:Oohkotokia color:1900s bar:NAM12 at:2013 mark:(line,black) text:Taohelong color:1900s bar:NAM13 at:2014 mark:(line,black) text:Chuanqilong color:1900s bar:NAM14 at:2014 mark:(line,black) text:Crichtonpelta color:1900s bar:NAM15 at:2014 mark:(line,black) text:Zaraapelta color:1900s bar:NAM16 at:2014 mark:(line,black) text:Ziapelta color:1900s bar:NAM17 at:2015 mark:(line,black) text:Horshamosaurus color:1900s bar:NAM18 at:2015 mark:(line,black) text:Kunbarrasaurus color:1900s bar:NAM19 at:2017 mark:(line,black) text:Zuul color:1900s bar:NAM20 at:2017 mark:(line,black) text:Borealopelta color:1900s bar:NAM21 at:2018 mark:(line,black) text:Platypelta color:1900s bar:NAM22 at:2018 mark:(line,black) text:Jinyupelta color:1900s bar:NAM23 at:2018 mark:(line,black) text:Acantholipan color:1900s bar:NAM24 at:2018 mark:(line,black) text:Invictarx color:1900s bar:NAM25 at:2018 mark:(line,black) text:Akainacephalus color:1900s bar:NAM26 at:2020 mark:(line,black) text:Sinankylosaurus color:1900s bar:NAM27 at:2021 mark:(line,black) text:Stegouros

PlotData=

align:center textcolor:black fontsize:M mark:(line,black) width:25 shift:(7,-4) bar:period from:1830 till:1840 color:1800syears text:30s from:1840 till:1850 color:1800syears text:40s from:1850 till:1860 color:1800syears text:50s from:1860 till:1870 color:1800syears text:60s from:1870 till:1880 color:1800syears text:70s from:1880 till:1890 color:1800syears text:80s from:1890 till:1900 color:1800syears text:90s from:1900 till:1910 color:1900syears text:00s from:1910 till:1920 color:1900syears text:10s from:1920 till:1930 color:1900syears text:20s from:1930 till:1940 color:1900syears text:30s from:1940 till:1950 color:1900syears text:40s from:1950 till:1960 color:1900syears text:50s from:1960 till:1970 color:1900syears text:60s from:1970 till:1980 color:1900syears text:70s from:1980 till:1990 color:1900syears text:80s from:1990 till:2000 color:1900syears text:90s from:2000 till:2010 color:2000syears text:00s from:2010 till:2020 color:2000syears text:10s from:2020 till:2030 color:2000syears text:20s from:2030 till:2040 color:2000syears text:30s from:2040 till:2050 color:2000syears text:40s bar:era from:1830 till:1900 color:1800s text:19th from:1900 till:2000 color:1900s text:20th from:2000 till:2050 color:2000s text:21st

</timeline>

Prescientific

- The Delaware people of what is now New Jersey or Pennsylvania had a tradition regarding a hunting party that returned with a piece of an ancient bone supposedly belonging to a monster that killed humans. One of the village's wise men instructed people to burn bits of the bone in clay spoons with tobacco and make a wish while the concoction was still smoking. This ritual could bestow such favors as success in hunting, long life, and health for one's children. This tale might be inspired by local fossils, which include ankylosaurs, Coelosaurus, Dryptosaurus, and Hadrosaurus.[1]

- Traditional Navajo creation mythology portrays modern Earth as the most recent of a series of worlds. They believe that the earlier worlds were inhabited by monsters that were killed with lightning bolts wielded by the heroic Monster Slayers.[8] The most terrifying monster of the old worlds was the Big Gray Monster, Yeitso.[9] The Navajo of Arizona feared fossil remains, attributing them to his corpse. They believe that Yeitso's ghost still haunts his remains.[10] Yeitso's flint-like scales may have been inspired by the fossilized armored plates of various prehistoric creatures that once lived in what is now the western US. Ankylosaurs like Ankylosaurus are one such potential candidate for the source of Yeitso's armored hide. Others include non-ankylosaurs like the Permian amphibian Eryops, Triassic phytosaurs and Desmatosuchus, as well as other armored dinosaurs like Scutellosaurus or Stegosaurus.[2]

- The Piegan people of Alberta attributed the fossils of dinosaurs to the "grandfather of the buffalo" they left offerings of cloth and tobacco to this mythical creature near the Red Deer River. Ankylosaur remains are among those preserved in the area that helped inspire this legend and associated practice, as are the remains of ceratopsians, hadrosaurs, and carnivorous theropods.[3]

19th century

1830s

1832

- Quarry workers discovered a fossilized partial skeleton. The remains were sent to paleontologist Gideon Mantell, who recognized that they represented a significant scientific discovery.[11]

- Mantell reported the specimen discovered by quarry workers that would later be formally named Hylaeosaurus to the Geological Society.[11]

1833

- Gideon Mantell described the new genus and species Hylaeosaurus armatus.[12] This was the first ankylosaur ever discovered, although the group itself would not be recognized and named for many years.[13]

1840s

1842

Early April

- Sir Richard Owen published his second report on British fossil reptiles, wherein he formally named the Dinosauria.[14] Hylaeosaurus was included as a founding member and was the third dinosaur to be named.[15]

1843

- Fitzinger described the new species Hylaeosaurus mantellii.[12]

1844

- Mantell described the new species Hylaeosaurus oweni.[12]

1850s

1856

- Joseph Leidy described the new genus and species Palaeoscincus costatus.[16] He considered it to be an herbivore.[7]

1858

- Sir Richard Owen published a study on Hylaeosaurus.[17]

1860s

1865

- Reverend William Fox discovered the Polacanthus type specimen.[18]

1867

- Sir Richard Owen described the new genus Polacanthus.[19] He also described the new genus and species Acanthopholis horridus.[19]

1869

- Harry Govier Seeley described the new species Acanthopholis eucercus and A. macrocercus and A. platypus and A. stereocercus. He also described the new genus and species Cryptosaurus eumerus.[19] He also described the new species Iguanodon phillipsii.[16]

1870s

1871

- Bunzel described the new genus and species Struthiosaurus austriacus.[12] He also described the new genus and species Danubiosaurus anceps.[19]

1875

- Seeley erected the new genus Priodontognathus to house the species Iguanodon phillipsii.[16]

1879

- Seeley described the new genus and species Anoplosaurus curtonotus and Anoplosaurus major.[19] Seeley also described the new genus and species Eucercosaurus tanyspondylus.[19] He also described the new genus and species Syngonosaurus macrocercus.[16]

1880s

1881

- Seeley described the new genus Crataeomus, with two new species: C. lepidophorus and C. pawlowitschii. He also described the new genus and species Hoplosaurus ischyrus, the new genus and species Pleuropeltis suessi,[12] and the new genus and species Rhadinosaurus alcinus.[16]

- Hulke described the new species Hylaeosaurus foxii.[19]

1882

- The British Museum of Natural History bought a large number of fossils from Rev. Fox, including the Polacanthus type specimen.[20]

1888

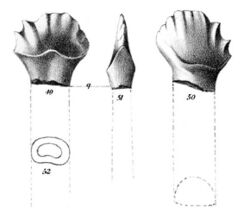

- Othniel Charles Marsh described the new genus and species Priconodon crassus.[16]

1889

- Marsh described the new genus and species Nodosaurus textilis.[19]

- Richard Lydekker described the new genus Cryptodraco to house the species Cryptosaurus eumerus.[19]

1890s

1890

- Marsh named the Nodosauridae.[21] He regarded them as relatives of the stegosaurs due to the shared presence of bony plates embedded in the skin.[5]

1892

- Marsh described the new genus and species Palaeoscincus latus.[16]

1893

- Lydekker described the new genus and species Sarcolestes leedsi.[19]

20th century

1900s

1901

- F. A. Lucas described the new species Stegosaurus marshi, and later reclassified it as Polacanthus marshi.[12]

1902

- Lawrence Lambe described the new genus and species Stereocephalus tutus.[21] He also described the new species Palaeoscincus asper.[16] He regarded ankylosaurs as herbivores.[7]

- Lucas erected the genus Hoplitosaurus to house the species "Polacanthus" marshi.[12]

- Franz Nopcsa described the new genus and species Onychosaurus hungaricus.[16]

1905

- Samuel Williston described the new genus and species Stegopelta landerensis.[19]

1908

- Brown described the new genus and species Ankylosaurus magniventris.[21] He also named the Ankylosauridae and Ankylosaurinae. He followed Marsh's 1890 suggestion that ankylosaurs and stegosaurs were close relatives.[22]

1909

- Wieland described the new genus and species Hierosaurus sternbergi.[16]

1910s

1914

- While collecting fossils in Dinosaur Provincial Park, William Edmund Cutler discovered the type specimen of an ankylosaur taxon that would later be named Scolosaurus cutleri in his honor. However, while undercutting the specimen it collapsed on him "resulting in serious upper body injuries."[23]

1915

- Nopcsa described the new species Struthiosaurus transylvanicus.[12]

1918

- Nopcsa described the new genus and species Leipsanosaurus noricus.[12]

1919

- Lambe described the new genus and species Panoplosaurus mirus.[21]

1920s

1923

- Henry Fairfield Osborn named the Ankylosauria.[5]

- Charles A. Matley described the new genus and species Lametasaurus indicus.[16]

1924

- Parks described the new genus and species Dyoplosaurus acutosquameus.[21]

- Hennig described the new species Polacanthus becklesi.[19]

1927

- Alfred Sherwood Romer published the first formal diagnosis for the Ankylosauria.[5] He observed that the anatomy of the stegosaur pelvis and hindlimb as well as their primarily Jurassic age distinguished them from the mainly Cretaceous ankylosaurs. As the Stegosauria originally included all armored dinosaurs, Romer's distinction marked the beginning of the modern use of the name to refer to the plate-backed and spike-tailed dinosaurs.[6]

1928

- Nopcsa described the new genus Scolosaurus.[21]

- Charles Sternberg described the new genus and species Edmontonia longiceps.[21]

1929

- Nopcsa described the new species Scolosaurus cutleri.[21]

- Nopcsa described the new genus and species Polacanthoides ponderosus, and the new species Rhodanosaurus lugdunensis.[16]

- Sternberg described the new genus and species Anodontosaurus lambei.[21]

1930s

1930

- Charles Whitney Gilmore described the new genus and species Palaeoscincus rugosidens.[12]

1932

- Sternberg described the new ichnogenus and species Tetrapodosaurus borealis from the Early Cretaceous Gething Formation of British Columbia, Canada. He attributed the tracks to ceratopsians, but they would later be attributed to ankylosaurs.[24]

1933

- Gilmore described the new genus and species Pinacosaurus grangeri.[22]

1934

- Chakravarti described the new genus and species Brachypodosaurus gravis.[19]

1935

- C. C. Young described the new species Pinacosaurus ninghsiensis.[22]

1936

- Mehl described the new species Nodosaurus coleii.[19]

1940s

1940

- Russell concluded that ankylosaurs chewed with a simple straight-up-and-down movement of the jaws and only fed on soft vegetation based on aspects of their skull and tooth anatomy.[7]

1950s

1952

- Evgeny Maleev described the new genus and species Syrmosaurus viminicaudus,[22] as well as the species S. disparoserratus.[16]

- Maleev described the new genus and species Talarurus plicatospineus.[22]

1953

- Birger Bohlin described the new genus and species Peishansaurus philemys. He also described the new genus and species Sauroplites scutiger, and the new genus and species Stegosaurides excavatus.[16]

1955

- Nicholas Hotton regarded ankylosaurs as herbivores.[7]

1956

- Maleev described the new species Dyoplosaurus giganteus.[22]

1960s

1960

- T. H. Eaton described the new genus and species Silvisaurus condrayi.[21]

1963

- F. H. Khakimov discovered a new dinosaur track site in Shirkent National Park, Tajikistan.[25]

- Zakharov and Khakimov reported the dinosaur track site discovered by the latter to the scientific literature.[25]

1964

- Zakharov described the new ichnogenus and species Macropodosaurus gravis. He attributed it to a theropod, but these tracks are more likely to have been produced by ankylosaurs.[25]

1969

- Haas interpreted the ankylosaur diet and consisting of soft plants that ankylosaurs chewed with a simple straight-up-and-down movement of the jaws based on their skull and tooth anatomy.[7]

1970s

1970

- John Ostrom described the new genus and species Sauropelta edwardsorum.[21]

1971

- Walter Coombs published landmark research into ankylosaur taxonomy, bringing order to a once "chaotic and confused" field of study. He recognized two main groups of ankylosaurs, the Ankylosauridae and Nodosauridae.[5] Coombs interpreted the ankylosaur diet as consisting of soft plants that ankylosaurs chewed with a simple straight-up-and-down movement of the jaws based on their skull and tooth anatomy.[7]

- Haubold reported the presence of the ichnospecies Metatetrapous valdensis from the Buckeburg Formation of Germany. This ichnospecies is attributed to ankylosaurs.[26]

1972

- Coombs observed that Euoplocephalus was so thoroughly armored that there was even a bony plate protecting its eyelids.[27]

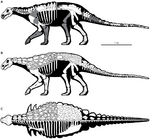

1977

- Teresa Maryanska described the new genus Tarchia for the species "Dyoplosaurus" giganteus. She also named the new species Tarchia kielanae and the new genus and species Saichania chulsanensis.[22] She followed the scheme proposed by Coombs earlier that decade dividing the ankylosaurs into ankylosaurids and nodosaurids.[5] She also made observations regarding ankylosaur limb posture, noting that while the hind limb was nearly straight up and down, the humerus was oriented at an angle downward and toward the rear of the animal. When studying the ankylosaur tail she noted that the centra of the vertebrae near its tip are fused, which would make it hard for the animal to raise the tail club very high.[7]

1978

- Kurzanov and Tumanova described the new genus and species Amtosaurus magnus.[19]

- Coombs published more work on ankylosaur taxonomy.[5] He noted that ankylosaurs were probably completely unable to walk on their hind legs and published further remarks on ankylosaur limb posture. He argued that while some researchers interpreted some aspects of ankylosaur forelimb anatomy as adaptations for digging, their hoof-like toe nails made this interpretation unlikely.[28]

1979

- Coombs interpreted the bony tendons near the tip of the ankylosaur tail as a means to convey the forces generated by the tail musculature closer to the animal's body all the way down to its club.[7]

1980s

1980

- Ralph Molnar described the new genus and species Minmi paravertebra.[22]

- Peter Galton described the new genus and species Dracopelta zbyszewskii.[12]

1982

- Delair described the new genus Vectensia.[12]

1983

- Tumanova described the new genus and species Shamosaurus scutatus.[22]

- Campbell reported the presence of dinosaur footprints in the Toro Toro Formation of Bolivia which he attributed to sauropods.[29]

1984

- Kenneth Carpenter attributed the ichnogenus Tetrapodosaurus reported by Sternberg from British Columbia in the 1930s to ankylosaurs rather than ceratopsians.[24] He argued that the most likely trackmaker was Sauropelta.[30]

- Leonardi described the dinosaur footprints reported by Campbell the previous year in detail and named them Ligabuichnium bolivianum. Rather than sauropods, Leonardi argued that these tracks were produced by ankylosaurs or ceratopsians although it was difficult ascertain which of these taxa were responsible due to the poor preservation of the tracks.[29]

1986

- Galton interpreted the ankylosaur diet and consisting of soft plants that ankylosaurs chewed with a simple straight-up-and-down movement of the jaws based on their skull and tooth anatomy.[7]

1987

- Paul Ensom described dinosaur footprints from the Purbeck Beds of England once thought to have been left by sauropods. They are now thought to have been left by ankylosaurs.[31]

- Tumanova erected the new genus Maleevus to house the species Syrmosaurus disparoserratus.[16] Tumanova followed the scheme proposed by Coombs earlier that decade dividing the ankylosaurs into ankylosaurids and nodosaurids.[5]

- Gasparini and others reported ankylosaur remains from Antarctica.[5]

1988

- Robert Bakker described the new genus and species Denversaurus schlessmani.[21] He also erected the new genus Chassternbergia for the species "Edmontonia" rugosidens.

1989

- Currie reported the discovery of a Tetrapodosaurus track from British Columbia. Although he could not confidently identify its stratigraphic origin, the rock preserving the tracks has since been attributed to the Dunvegan Formation.[32]

- A worker at the Smoky River Coal Mine near Grande Cache, Alberta alerted the Royal Tyrell Museum to the presence of dinosaur footprints in the area. This site would come to be recognized as the most important ankylosaur track site in the world.[33]

1990s

1990

- Coombs and Maryanska remarked that the boney secondary palate of the ankylosaur skull would have strengthened it by acting as a brace.[7]

- A well-preserved skeleton of Minmi was excavated from the Allaru Formation in Queensland, Australia by the Queensland Museum and catalogued as QM F18101. The skeleton was mostly articulated, including its armor.[34] Since most ankylosaur specimens do not preserve the life arrangement of their armor, QM F18101 represented a rare find.[35] The specimen also preserved the animal's gut contents, the first to be discovered in any armored dinosaur.[36]

1991

- Lockley argued that the supposed sauropod tracks reported by Ensom from the Purbeck Beds of Dorset, England were actually made by ankylosaurs.[37]

- Frank DeCourten discovered dinosaur tracks preserved in the Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah that were likely produced by ankylosaurs.[38]

1993

- Tumanova described the new genus and species Tsagantegia longicranialis.[22]

- Jerzykiewicz and others reported the presence of borings of unknown cause on the bones of some juvenile Pinacosaurus grangeri from Bayan Mandahu, Inner Mongolia, China.[39]

- Z. Dong described the new genus and species Tianchisaurus nedegoaperferima.[16]

- Thulborn proposed that the tail club of ankylosaurs may actually have functioned as a "false head" meant to distract predators. However, this hypothesis has not received much support from the paleontological community, and has been criticized as "dubiou[s]".[7]

- Grady published an illustration of an ankylosaur trackway from the "Mine" site in the Smoky River Coal Mine at Grande Cache, Alberta.[40]

1994

- Kirkland and Carpenter described the new genus and species Mymoorapelta maysi.[12]

- Psihoyos and Knoebber described a dinosaur track site in the Smoky Hill Coal Mine of Grande Cache, Alberta and reported that the site had been destroyed in a rock slide.[41]

- Whyte and Romano described the new ichnogenus and species Deltapodus brodericki for dinosaur footprints discovered in the Aalenian-Bajocian Saltwick Formation of Yorkshire, England. The authors attributed the tracks to sauropods, but they may actually have been made by ankylosaurs.[42]

- Leonardi concluded that the Bolivian Ligabuichnium tracks were made by an ankylosaur after all.[29]

1995

- Carpenter, Dilkes, and Weishampel erected the new genus Niobrarasaurus to house the species Hierosaurus coleii.[19]

- Coombs studied the anatomy of the tail of Euoplocephalus and concluded that its club was held just slightly off the ground rather than dragging or held and a significant height. He reiterated observations previously made in 1977 by Maryanska that the fusion of the vertebral centra near the tip of the animal's tail would make it difficult to raise very high.[7]

- Coombs described the new genus and species Texasetes pleurohalio.[19]

1996

- Lee described the new genus and species Pawpawsaurus campbelli.[21]

- Molnar reported the existence of a second species of Minmi but did not name it.[22]

- Blows described the new species Polacanthus rudgwickensis.[19]

1997

- Witmer studied archosaur "craniofacial pneumaticity". He concluded that rather than performing a biological function, paranasal sinuses in archosaurs "are best explained as an optimization of skull architecture". This cast doubt on various researchers' interpretations of the sometimes complex nasal cavities and sinus systems possessed by ankylosaurs. Past workers had thought that these cavities and sinuses may have given ankylosaurs an improved sense of smell, housed glands, acted as a resonating chamber for loud vocalizations, or helped conserve body heat and moisture.[7]

1998

- Carpenter, Miles, and Cloward described the new genus and species Gargoyleosaurus parkpinorum.[22]

- Kirkland described the new genus and species Gastonia burgei.[22]

- Pang and Cheng described the new genus and species Tianzhenosaurus youngi.[22]

- Barret and others described the new genus and species Shanxia tianzhensis.[16]

- Sereno defined the ankylosaurs as all eurypods more closely related to Ankylosaurus than to Stegosaurus.[43]

- McCrea and Currie described the dinosaur tracks discovered in the Smoky River Coal Mine at Grand Cache, Alberta. They noted that this was the most important ankylosaur track site ever discovered.[33]

- McCrea and others reported the first known ankylosaur skin impression to be preserved in a footprint tracks preserved in the Dunvegan Formation near Pouce Coupe, Alberta.[44]

1999

- Godefroit and others described the new species Pinacosaurus mephistocephalus.[22]

- Sullivan described the new genus and species Nodocephalosaurus kirtlandensis.[21]

- Carpenter and others described the new genus and species Animantarx ramaljonesi.[12]

- Lockley and others described the 1991 possible ankylosaur footprint discovery in Utah.[45]

- Ishigaki reported possible ankylosaur footprints from the Djadokhta Formation of Mongolia.[46]

21st century

2000s

2000

- Ford described the new species Edmontonia australis[19] and the new genus and species Glyptodontopelta mimus.[19]

- Molnar and Clifford reported fossilized gut contents in a specimen of Minmi, which consisted of plant matter.[39]

2001

- Rybczynsky and Vickaryous studied the jaws and teeth of Euoplocephalus. Contrary to decades of support for ankylosaurs chewing with a simple straight-up-and-down movement, they noticed visible wear facets and microscopic grooves that could only be explained by relatively complex jaw movements.[7]

- Barrett reported wear facets on the teeth of Tarchia.[7]

- Molnar and Clifford described the gut contents preserved in a specimen of the Australian ankylosaur Minmi.[47] This specimen is catalogued by the Queensland Museum as QM F18101 and was excavated by the museum from near the Flinders River in 1990.[48] The stomach contents consisted of plant vascular tissue, fruiting bodies, seeds, and possible fern spores.[49] Molnar and Clifford described it as the most reliable evidence for the diet of an herbivorous dinosaur ever discovered.[50]

- McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer observed that by this point in the history of ankylosaur research, ankylosaurs track fossils had been reported from North America, South America, Asia, and Europe. Most of these trackways were preserved in moist floodplain habitats where plant life was abundant.[7] They attributed the Metatetrapous valdensis tracks from the Buckeburg Formation of Germany reported by Haubold in 1971 to ankylosaurs.[26] They similarly argued that Macropodosaurus gravis of Tajikistan was produced by an ankylosaur rather than a theropod.[25] The authors reported a single possible ankylosaur footprint from the Dakota Group of Baca County, Colorado.[51] They also proposed that several footprint specimens collected from the Blackhawk Formation of Utah may have been ankylosaurian.[52]

- Vickaryous and others described the new genus and species Gobisaurus domoculus.[22]

- Carpenter and others described the new genus and species Cedarpelta bilbeyhallorum.[21]

- Xu, Wang, and You described the new genus and species Liaoningosaurus paradoxus.[19]

- Ford and Kirkland described the new genus and species Aletopelta coombsi.[19]

2002

- Dong described the new genus and species Crichtonsaurus bohlini.[12]

- Averianov described the new genus and species Amtosaurus archibaldi.[19]

2003

- Garcia and Pereda-Superbiola described the new species Struthiosaurus languedocensis.[12]

- Vickaryous and Russell described the common ways ankylosaur skulls were distorted after death that could potentially confound anatomical interpretation. They noted a relationship between this tendency to suffer distortion and their unusual cranial traits like the fusion of the skull bones and their "embossing" cranial ornamentation.[39]

2004

- Averianov, 2002, vide Parish & Barrett, 2004 described the new genus and species Bissektipelta archibaldi.[53]

2005

- Ősi described the new genus and species Hungarosaurus tormai.[54]

2006

- Salgado and Gasparini described the new genus and species Antarctopelta oliveroi.[55]

2007

- Lü Junchang; Jin Xingsheng; Sheng Yiming; Li Yihong described the new genus and species Zhejiangosaurus lishuiensis.[56]

- Xu and others described the new genus and species Zhongyuansaurus luoyangensis.[57]

2008

- Carpenter and others described the new genus and species Peloroplites cedrimontanus[58]

- Burns synonymizes Edmontonia australis with Glyptodontopelta mimus and confirms the validity of the latter[59]

2009

- Miles and Miles described the new genus and species Minotaurasaurus ramachandrani.[60]

- Parsons and Parsons described the new genus and species Tatankacephalus cooneyorum.[61]

- Arbour and others resurrect the genus and species Dyoplosaurus acutosquameus Parks, 1924[62]

2010s

2011

- Burns and Sullivan described the new genus and species Ahshislepelta minor.[63]

- Burns and others describe new juvenile specimens of Pinacosaurus grangeri[64]

- Stanford, Weishampel, and DeLeon described the new genus and species Propanoplosaurus marylandicus.[65]

2013

- Chen and others described the new genus and species Dongyangopelta yangyanensis.[66]

- Kirkland and others described the new genus and species Europelta carbonensis.[67]

- Penkalski described the new genus and species Oohkotokia horneri.[68]

- Yang and others described the new genus and species Taohelong jinchengensis.[69]

2014

- Han and others described the new genus and species Chuanqilong chaoyangensis.[70]

- Arbour and Currie described the new genus Crichtonpelta.[71]

- Victoria M. Arbour, Philip J. Currie, and Demchig Badamgarav described the new genus and species Zaraapelta nomadis.[72]

- Arbour and others described the new genus and species Ziapelta sanjuanensis.[73]

2015

- Blows described the new genus Horshamosaurus.[74]

- Leahey and others described the new genus and species Kunbarrasaurus ieversi.[75]

- Burns and others describe juvenile material from Pinacosaurus grangeri collected during the Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition in 1969–1970[76]

2017

- Arbour and Evans describe a new ankylosaur, Zuul crurivastator[77][78]

- Brown and others described the new genus and species Borealopelta markmitchelli.[79]

- Penkalski and Tumanova described the new species Tarchia teresae.[citation needed]

2018

- Penkalski described the new species Scolosaurus thronus and Anodontosaurus inceptus and the new genus Platypelta.[citation needed]

- Zheng and others name the new genus and species Jinyunpelta sinensis.[80]

- Rivera-Sylva and others described the new genus and species Acantholipan gonzalezi.[81]

- Wiersma and Irmis described the new genus and species Akainacephalus johnsoni.[82]

- McDonald and Wolfe described the new genus and species Invictarx zephyri.[83]

2019

- Plates of an armored dinosaur from the Lower Jurassic (Sinemurian-Pliensbachian) Lower Kota Formation (India ) are redescribed by Galton (2019), who considers these fossils to be more similar to plates of ankylosaurians than basal thyreophorans, and interprets them as the earliest ankylosaurian fossils reported so far.[84]

- Description of an assemblage of 12 partial, articulated or associated ankylosaurian skeletons and thousands of isolated bones and teeth from the Cretaceous (Santonian) Iharkút vertebrate locality (Hungary) was published by Ősi et al. (2019).[85]

- A study on the evolution of morphological traits associated with tail weaponry in ankylosaurs and glyptodonts, aiming to quantitatively test the hypothesis that tail weaponry of these groups is an example of convergent evolution, is published by Arbour & Zanno (2019).[86]

- A study on the taphonomy and histology of the ornithischian (ankylosaurian and ornithopod) fossils from the La Cantalera-1 site (Lower Cretaceous Blesa Formation, Spain ) is published by Perales-Gogenola et al. (2019).[87]

2020s

2020

- An isolated caudal vertebra representing the first evidence of the presence of an ankylosaur in the Upper Jurassic Qigu Formation (China) is described by Augustin et al. (2020).[88]

- A study aiming to determine the social lifestyle of ankylosaurs, as indicated by anatomy, taphonomic history, ontogenetic composition of the mass death assemblages and inferred habitat characteristics, is published by Botfalvai, Prondvai & Ősi (2020).[89]

- Redescription of the anatomy of the holotype specimens of Hylaeosaurus armatus and Polacanthus foxii, and a study on the taxonomy of all ankylosaur specimens from the British Wealden Supergroup, is published by Raven et al. (2020).[90]

- Fossil stomach contents preserved within the abdominal cavity of the holotype specimen of Borealopelta markmitchelli are described by Brown et al. (2020).[91]

- Description of the anatomy of braincases of three specimens of Bissektipelta archibaldi is published by Kuzmin et al. (2020).[92]

- Wang et al. (2020) describe the new genus and species of ankylosaur, Sinankylosaurus.[93]

See also

- History of paleontology

Footnotes

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Mayor (2005); "Smoking the Monster's Bone: An Ancient Delaware Fossil Legend," pages 68–69.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 Mayor (2005); "The Monsters," page 122.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Mayor (2005); "Blackfeet and Ojibwe Fossil Discoveries," page 292.

- ↑ Sarjeant (1999); "Further Finds in England," pages 9–10.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel (2004); "Introduction", page 363.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Galton and Upchurch (2004); "Introduction", page 343.

- ↑ Jump up to: 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel (2004); "Paleoecology and Behavior", page 392.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "The Monsters," page 119.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Moore (2014); "1832" (1), page 31.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel (2004); "Table 17.1: Ankylosauria", page 366.

- ↑ For Hylaeosaurus as the first ankylosaur, see Sarjeant (1999); "Further Finds in England," pages 9–10. For the date of the description of Ankylosauria, see Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel (2004); "Introduction", page 363.

- ↑ Torrens (1999); "Politics and Paleontology", page 182.

- ↑ Torrens (1999); "Politics and Paleontology", page 184.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 16.12 16.13 16.14 16.15 16.16 Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel (2004); "Table 17.1: Ankylosauria", page 368.

- ↑ Moore (2014); "1858" (3), page 53.

- ↑ Moore (2014); "1865" (3), page 61.

- ↑ Jump up to: 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 19.13 19.14 19.15 19.16 19.17 19.18 19.19 19.20 19.21 19.22 Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel (2004); "Table 17.1: Ankylosauria", page 367.

- ↑ Moore (2014); "1882" (1), page 91.

- ↑ Jump up to: 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 21.11 21.12 21.13 21.14 Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel (2004); "Table 17.1: Ankylosauria", page 365.

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.00 22.01 22.02 22.03 22.04 22.05 22.06 22.07 22.08 22.09 22.10 22.11 22.12 22.13 22.14 22.15 Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel (2004); "Table 17.1: Ankylosauria", page 364.

- ↑ Tanke (2010); "Background and Collection History," page 542.

- ↑ Jump up to: 24.0 24.1 McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Gething Formation, British Columbia (Aptian-Albian)", page 422.

- ↑ Jump up to: 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Shirabad Suite, Tadjikistan (Albian)", page 433.

- ↑ Jump up to: 26.0 26.1 McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Wealden Beds, Germany (Berriasian)", pages 421-422.

- ↑ Vickaryous, Russell, and Currie (2001); "Testing the Hypothesis", page 327.

- ↑ Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel (2004); "Paleoecology and Behavior", pages 391–392.

- ↑ Jump up to: 29.0 29.1 29.2 McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Torotoro Formation, Bolivia (Campanian)", page 442.

- ↑ McCrea (2000); "Tetrapodosaurus borealis Sternberg, 1932", page 41.

- ↑ McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Purbeck Beds, England (Berriasian)", page 421.

- ↑ McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Dunvegan Formation, Alberta and Northeast British Columbia (Cenomanian)", page 437.

- ↑ Jump up to: 33.0 33.1 McCrea (2000); "1.2 Previous work on the Gates Formation", page 2.

- ↑ Molnar (2001); "Introduction", page 342.

- ↑ Molnar (2001); "Introduction", page 341.

- ↑ Molnar and Clifford (2001); "Introduction", pages 399-400.

- ↑ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The First Ankylosaur Tracks," pages 182-183.

- ↑ McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Cedar Mountain Formation, Utah (Albian-Cenomanian)", page 433.

- ↑ Jump up to: 39.0 39.1 39.2 Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel (2004); "Taphonomy", page 391.

- ↑ McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Gates Formation, Grande Cache, Alberta (Lower Albian)", page 429.

- ↑ McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Gates Formation, Grande Cache, Alberta (Lower Albian)", page 423.

- ↑ McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Saltwick Formation, England (Aalenian-Bajocian)", page 421.

- ↑ Vickaryous, Maryanska, and Weishampel (2004); "Definition and Diagnosis", page 363.

- ↑ McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Dunvegan Formation, Alberta and Northeast British Columbia (Cenomanian)", page 440.

- ↑ McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Cedar Mountain Formation, Utah (Albian-Cenomanian)", pages 433-434.

- ↑ McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Djadokhta Formation, Mongolia (Campanian)", page 441.

- ↑ Molnar and Clifford (2001); "Abstract", page 399.

- ↑ For date and location of discovery, see Molnar (2001); "Introduction", page 342. For catalogue number and stomach contents, see Molnar and Clifford (2001); "Introduction", page 399.

- ↑ Molnar and Clifford (2001); "Description", page 401.

- ↑ Molnar and Clifford (2001); "Introduction", page 400.

- ↑ McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Dakota Group (Albian-Cenomanian)", page 435.

- ↑ McCrea, Lockley, and Meyer (2001); "Blackhawk Formation, Utah (Campanian)", page 440.

- ↑ Parish and Barrett (2004); "Abstract", page 299.

- ↑ Ősi (2005); "Abstract", page 370.

- ↑ Salgado and Gasparini (2006); "Abstract", page 199.

- ↑ Lü et al. (2007); "Abstract", page 344.

- ↑ Xu et al. (2007); "Abstract", page 433.

- ↑ Carpenter et al. (2008); "Abstract", page 1089.

- ↑ Burns, Michael E. (2008-12-12). "Taxonomic utility of ankylosaur (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) osteoderms: Glyptodontopelta mimus Ford, 2000: a test case". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28 (4): 1102–1109. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1102. ISSN 0272-4634. Bibcode: 2008JVPal..28.1102B.

- ↑ Miles and Miles (2009); "Abstract", page 65.

- ↑ Parsons and Parsons (2009); "Abstract", page 721.

- ↑ Arbour, Victoria M.; Burns, Michael E.; Sissons, Robin L. (2009-12-12). "A redescription of the ankylosaurid dinosaur Dyoplosaurus acutosquameus Parks, 1924 (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) and a revision of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (4): 1117–1135. doi:10.1671/039.029.0405. ISSN 0272-4634. Bibcode: 2009JVPal..29.1117A.

- ↑ Burns and Sullivan (2011); "Abstract", page 169.

- ↑ Burns, Michael E.; Currie, Philip J.; Sissons, Robin L.; Arbour, Victoria M. (2011). "Juvenile specimens of Pinacosaurus grangeri Gilmore, 1933 (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) from the Late Cretaceous of China, with comments on the specific taxonomy of Pinacosaurus". Cretaceous Research 32 (2): 174–186. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.11.007. Bibcode: 2011CrRes..32..174B.

- ↑ Stanford, Weishampel, and DeLeon (2011); "Abstract", page 916.

- ↑ Chen et al. (2013); "Abstract", page 658.

- ↑ Kirkland et al. (2013); "Abstract", page 1.

- ↑ Penkalski (2013); "Abstract", page 617.

- ↑ Yang et al. (2013); "Abstract", page 265.

- ↑ Han et al. (2014); "Abstract", page 1.

- ↑ Arbour and Currie (2015); "Abstract".

- ↑ Arbour, Currie, and Badamgarav (2014); "Abstract", page 631.

- ↑ Arbour et al. (2014); "Abstract", page 1.

- ↑ Blows (2015); in passim.

- ↑ Leahey et al. (2015); in passim.

- ↑ Burns, Michael E.; Tumanova, Tatiana A.; Currie, Philip J. (January 2015). "Postcrania of juvenile Pinacosaurus grangeri (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Alagteeg Formation, Alag Teeg, Mongolia: implications for ontogenetic allometry in ankylosaurs". Journal of Paleontology 89 (1): 168–182. doi:10.1017/jpa.2014.14. ISSN 0022-3360. Bibcode: 2015JPal...89..168B.

- ↑ Arbour, Victoria M.; Evans, David C. (10 May 2017). "A new ankylosaurine dinosaur from the Judith River Formation of Montana, USA, based on an exceptional skeleton with soft tissue preservation". Royal Society Open Science 4 (5): 161086. doi:10.1098/rsos.161086. PMID 28573004. Bibcode: 2017RSOS....461086A.

- ↑ "Zuul, Destroyer of Shins". Royal Ontario Museum. http://www.rom.on.ca/en/collections-research/research-community-projects/zuul.

- ↑ Brown, Caleb M.; Henderson, Donald M.; Vinther, Jakob; Fletcher, Ian; Sistiaga, Ainara; Herrera, Jorsua; Summons, Roger E. (August 2017). "An Exceptionally Preserved Three-Dimensional Armored Dinosaur Reveals Insights into Coloration and Cretaceous Predator-Prey Dynamics". Current Biology 27 (16): 2514–2521.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.06.071. PMID 28781051. http://www.cell.com/current-biology/pdf/S0960-9822(17)30808-4.pdf. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ↑ Wenjie Zheng; Xingsheng Jin; Yoichi Azuma; Qiongying Wang; Kazunori Miyata; Xing Xu (2018). "The most basal ankylosaurine dinosaur from the Albian–Cenomanian of China, with implications for the evolution of the tail club". Scientific Reports 8 (1): Article number 3711. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-21924-7. PMID 29487376. Bibcode: 2018NatSR...8.3711Z.

- ↑ Héctor E. Rivera-Sylva; Eberhard Frey; Wolfgang Stinnesbeck; Gerardo Carbot-Chanona; Iván E. Sanchez-Uribe; José Rubén Guzmán-Gutiérrez (2018). "Paleodiversity of Late Cretaceous Ankylosauria from Mexico and their phylogenetic significance". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology 137 (1): 83–93. doi:10.1007/s13358-018-0153-1. Bibcode: 2018SwJP..137...83R.

- ↑ Jelle P. Wiersma; Randall B. Irmis (2018). "A new southern Laramidian ankylosaurid, Akainacephalus johnsoni gen. et sp. nov., from the upper Campanian Kaiparowits Formation of southern Utah, USA". PeerJ 6: e5016. doi:10.7717/peerj.5016. PMID 30065856.

- ↑ Andrew T. McDonald; Douglas G. Wolfe (2018). "A new nodosaurid ankylosaur (Dinosauria: Thyreophora) from the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico". PeerJ 6: e5435. doi:10.7717/peerj.5435. PMID 30155354.

- ↑ Peter M. Galton (2019). "Earliest record of an ankylosaurian dinosaur (Ornithischia: Thyreophora): Dermal armor from Lower Kota Formation (Lower Jurassic) of India". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen 291 (2): 205–219. doi:10.1127/njgpa/2019/0800.

- ↑ Attila Ősi; Gábor Botfalvai; Gáspár Albert; Zsófia Hajdu (2019). "The dirty dozen: taxonomical and taphonomical overview of a unique ankylosaurian (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) assemblage from the Santonian Iharkút locality, Hungary". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments 99 (2): 195–240. doi:10.1007/s12549-018-0362-z. Bibcode: 2019PdPe...99..195O. http://real.mtak.hu/103219/1/Osi_et_al_MS_corrected_dirty_dozen.pdf.

- ↑ Victoria M. Arbour; Lindsay E. Zanno (2019). "Tail weaponry in ankylosaurs and glyptodonts: an example of a rare but strongly convergent phenotype". The Anatomical Record 303 (4): 988–998. doi:10.1002/ar.24093. PMID 30835954.

- ↑ Leire Perales-Gogenola; Javier Elorza; José Ignacio Canudo; Xabier Pereda-Suberbiola (2019). "Taphonomy and palaeohistology of ornithischian dinosaur remains from the Lower Cretaceous bonebed of La Cantalera (Teruel, Spain)". Cretaceous Research 99: 316–334. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.01.024. Bibcode: 2019CrRes..98..316P. http://zaguan.unizar.es/record/87680.

- ↑ Felix J. Augustin; Andreas T. Matzke; Michael W. Maisch; Hans-Ulrich Pfretzschner (2020). "First evidence of an ankylosaur (Dinosauria, Ornithischia) from the Jurassic Qigu Formation (Junggar Basin, NW China) and the early fossil record of Ankylosauria". Geobios 61: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2020.06.005. Bibcode: 2020Geobi..61....1A.

- ↑ Gábor Botfalvai; Edina Prondvai; Attila Ősi (2020). "Living alone or moving in herds? A holistic approach highlights complexity in the social lifestyle of Cretaceous ankylosaurs". Cretaceous Research 118: Article 104633. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104633. http://real.mtak.hu/112909/1/Botfalvai%20et%20al_pre_Proof.pdf.

- ↑ Thomas J. Raven; Paul M. Barrett; Stuart B. Pond; Susannah C. R. Maidment (2020). "Osteology and Taxonomy of British Wealden Supergroup (Berriasian–Aptian) Ankylosaurs (Ornithischia, Ankylosauria)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 40 (4): e1826956. doi:10.1080/02724634.2020.1826956. Bibcode: 2020JVPal..40E6956R.

- ↑ Caleb M. Brown; David R. Greenwood; Jessica E. Kalyniuk; Dennis R. Braman; Donald M. Henderson; Cathy L. Greenwood; James F. Basinger (2020). "Dietary palaeoecology of an Early Cretaceous armoured dinosaur (Ornithischia; Nodosauridae) based on floral analysis of stomach contents". Royal Society Open Science 7 (6): Article ID: 200305. doi:10.1098/rsos.200305. PMID 32742695. Bibcode: 2020RSOS....700305B.

- ↑ Ivan Kuzmin; Ivan Petrov; Alexander Averianov; Elizaveta Boitsova; Pavel Skutschas; Hans-Dieter Sues (2020). "The braincase of Bissektipelta archibaldi — new insights into endocranial osteology, vasculature, and paleoneurobiology of ankylosaurian dinosaurs". Biological Communications 65 (2): 85–156. doi:10.21638/spbu03.2020.201.

- ↑ Wang, K. B.; Zhang, Y. X.; Chen, J.; Chen, S. Q.; Wang, P. Y. (2020). "A new ankylosaurian from the Late Cretaceous strata of Zhucheng, Shandong Province" (in Chinese). Geological Bulletin of China 39 (7): 958–962. http://dzhtb.cgs.cn/gbcen/ch/reader/create_pdf.aspx?file_no=20200703&flag=1&year_id=2020&quarter_id=7.

References

- Arbour, Victoria M.; Burns, Michael E.; Sullivan, Robert M.; Lucas, Spencer G.; Cantrell, Amanda K.; Fry, Joshua; Suazo, Thomas L. (24 September 2014). "A New Ankylosaurid Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous (Kirtlandian) of New Mexico with Implications for Ankylosaurid Diversity in the Upper Cretaceous of Western North America". PLOS ONE 9 (9): e108804. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108804. PMID 25250819. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9j8804A.

- Victoria M. Arbour; Philip J. Currie (2015). "Systematics, phylogeny and palaeobiogeography of the ankylosaurid dinosaurs". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 14 (5): 1–60. doi:10.1080/14772019.2015.1059985.

- Arbour, V. M.; Currie, P. J.; Badamgarav, D. (2014). "The ankylosaurid dinosaurs of the Upper Cretaceous Baruungoyot and Nemegt formations of Mongolia". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 172 (3): 631–652. doi:10.1111/zoj.12185.

- Aviarianov, A. O. (2002). "An ankylosaurid (Ornithischia: Ankylosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Bissekty Formation of Uzbekistan". Bull. Inst. R. Sci. Nat. Belg. Sci. Terre 72: 97–110.

- Blows, William T. (2015). British Polacanthid Dinosaurs – Observations on the History and Palaeontology of the UK Polacanthid Armoured Dinosaurs and their Relatives. Siri Scientific Press. pp. 220.

- Michael E. Burns; Robert M. Sullivan (2011). "A new ankylosaurid from the Upper Cretaceous Kirtland Formation, San Juan Basin, with comments on the diversity of ankylosaurids in New Mexico". Fossil Record 3. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin 53: 169–178. http://www.robertmsullivanphd.com/uploads/162._Burns_and_Sullivan__Ahshislepelta__COLOR.pdf.

- Carpenter, Kenneth; Bartlett, Jeff; Bird, John; Barrick, Reese (2008). "Ankylosaurs from the Price River Quarries, Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), east-central Utah". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28 (4): 1089–1101. doi:10.1671/0272-4634-28.4.1089. Bibcode: 2008JVPal..28.1089C.

- Rongjun Chen, Wenjie Zheng, Yoichi Azuma, Masateru Shibata, Tianliang Lou, Qiang Jin and Xingsheng Jin (2013). "A New Nodosaurid Ankylosaur from the Chaochuan Formation of Dongyang, Zhejiang Province, China". Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition) 87 (3): 658–671. doi:10.1111/1755-6724.12077. Bibcode: 2013AcGlS..87..658C. http://www.geojournals.cn/dzxben/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?file_no=201303003&flag=1.

- Galton, Peter; Upchurch, Paul (2004). "16: Stegosauria". in Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka. The Dinosauria (2 ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Han, F.; Zheng, W.; Hu, D.; Xu, X.; Barrett, P.M. (2014). "A New Basal Ankylosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Liaoning Province, China". PLOS ONE 9 (8): e104551. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104551. PMID 25118986. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...9j4551H.

- Kirkland, J. I.; Alcalá, L.; Loewen, M. A.; Espílez, E.; Mampel, L.; Wiersma, J. P. (2013). Butler, Richard J. ed. "The Basal Nodosaurid Ankylosaur Europelta carbonensis n. gen., n. sp. From the Lower Cretaceous (Lower Albian) Escucha Formation of Northeastern Spain". PLOS ONE 8 (12): e80405. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080405. PMID 24312471. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...880405K.

- Lucy G. Leahey, Ralph E. Molnar, Kenneth Carpenter, Lawrence M. Witmer and Steven W. Salisbury (2015). "Cranial osteology of the ankylosaurian dinosaur formerly known as Minmi sp. (Ornithischia: Thyreophora) from the Lower Cretaceous Allaru Mudstone of Richmond, Queensland, Australia". PeerJ 3: e1475. doi:10.7717/peerj.1475. PMID 26664806.

- Lockley, Martin G.; Meyer, C. A. (2000). Dinosaur Tracks and other fossil footprints of Europe. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10710-5.

- Junchang, Lü; Jin Xingsheng; Sheng Yiming; Li Yihong (2007). "New nodosaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Lishui, Zhejiang Province, China". Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition) 81 (3): 344–350. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2007.tb00958.x. Bibcode: 2007AcGlS..81..344L.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2005). Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11345-6.

- McCrea, Richard T. (2000). Vertebrate palaeoichnology of the lower cretaceous (lower Albian) gates formation of Alberta (PDF) (Thesis).

- McCrea, R. T.; Meyer, C. A. (2001). "Global distribution of purported ankylosaur track occurrences". in Carpenter, Kenneth. The Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 413–454.

- Miles, Clifford A.; Miles, Clark J. (2009). "Skull of Minotaurasaurus ramachandrani, a new Cretaceous ankylosaur from the Gobi Desert". Current Science 96 (1): 65–70. http://www.dinosaures-web.com/sites/default/files/publications/65.pdf.

- Molnar, Ralph E. (2001). "Armor of the small ankylosaur Minmi". in Carpenter, Kenneth. The Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 341–362. ISBN 978-0-253-33964-5.

- Molnar, Ralph E.; Clifford, H. Trevor (2001). "An ankylosaurian cololite from Queensland, Australia". in Carpenter, Kenneth. The Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 399–412. ISBN 978-0-253-33964-5.

- Moore, Randy (2014). Dinosaurs by the Decades: A Chronology of the Dinosaur in Science and Popular Culture. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. pp. 472. ISBN 978-0-313-39364-8.

- Ősi, Attila (2005). "Hungarosaurus tormai, a new ankylosaur (Dinosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous of Hungary". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (2): 370–383. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0370:htanad2.0.co;2].

- Parish, Jolyon; Barrett, Paul (2004). "A reappraisal of the ornithischian dinosaur Amtosaurus magnus Kurzanov and Tumanova 1978, with comments on the status of A. archibaldi Averianov 2002". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 41 (3): 299–306. doi:10.1139/e03-101. Bibcode: 2004CaJES..41..299P.

- Parsons, W.L.; Parsons, K.M. (2009). "A new ankylosaur (Dinosauria: Ankylosauria) from the Lower Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of central Montana". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 46 (10): 721–738. doi:10.1139/E09-045. Bibcode: 2009CaJES..46..721S.

- Penkalski, P. (2013). "A new ankylosaurid from the late Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana, USA". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.2012.0125.

- Salgado, L.; Gasparini, Z. (2006). "Reappraisal of an ankylosaurian dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of James Ross Island (Antarctica).". Geodiversitas 28 (1): 119–135.

- Sarjeant, William A. S. (1999). "The Earliest Discoveries". in Farlow, J.O.. The Complete Dinosaur. Indiana University Press. pp. 3–11. ISBN 978-0-253-21313-6.

- Ray Stanford; David B. Weishampel; Valerie B. DeLeon (2011). "The First Hatchling Dinosaur Reported from the Eastern United States: Propanoplosaurus marylandicus (Dinosauria: Ankylosauria) from the Early Cretaceous of Maryland, U.S.A.". Journal of Paleontology 85 (5): 916–924. doi:10.1666/10-113.1. Bibcode: 2011JPal...85..916S.

- Tanke, D. H. (2010). "Lost in plain sight: rediscovery of William E. Cutler's missing Eoceratops". in Ryan, M. J.; Chinnery-Allgeier, B. J.; Eberth, D. A.. New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium. Life of the Past. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 541–550.

- Torrens, Hugh (1999). "Politics and Paleontology: Richard Owen and the Invention of Dinosaurs". in Farlow, J.O.. The Complete Dinosaur. Indiana University Press. pp. 318–340. ISBN 978-0-253-21313-6.

- Vickaryous, M. K.; A. P. Russell; P. J. Currie (2001). "Cranial Ornamentation of Ankylosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora): Reappraisal of Developmental Hypotheses". in Carpenter, Kenneth. The Armored Dinosaurs. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 341–362. ISBN 978-0-253-33964-5.

- Vickaryous, M. K.; Maryańska, T.; Weishampel, D. B. (2004). "Ankylosauria". in Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H.. The Dinosauria (2 ed.). Berkeley: The University of California Press. pp. 363–392.

- Xu, Li; Lu Junchang; Zhang Xingliao; Jia Songhai; Hu Weiyong; Zhang Jiming; Wu Yanhua; Ji Qiang (2007). "New nodosaurid ankylosaur from the Cretaceous of Ruyang, Henan Province". Acta Geologica Sinica 81 (4): 433–438. http://paleoglot.org/files/Li&%2007.pdf.

- Yang J.-T.; You H.-L.; Li D.-Q.; Kong D.-L. (2013). "First discovery of polacanthine ankylosaur dinosaur in Asia" (in zh, en). Vertebrata PalAsiatica 51 (4): 265–277. http://www.ivpp.cas.cn/cbw/gjzdwxb/xbwzxz/201312/P020131205318740255664.pdf.

External links

|