Biology:Timema

| Timema | |

|---|---|

| |

| Timema genevievae on the leaves of chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Phasmatodea |

| Family: | Timematidae |

| Genus: | Timema Scudder, 1895 |

| Species | |

|

21, and see text | |

| |

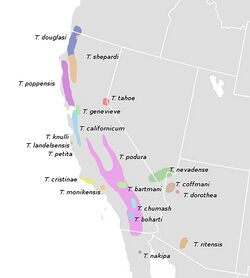

| Geographical distribution of Timema species in North America (Law & Crespi, 2002). T. morongense is found west of T. chumash but the extent of its full range is unknown.[1] | |

Timema is a genus of relatively short-bodied, stout and wingless stick insects native to the far western United States, and the sole extant member of the family Timematidae. The genus was first described in 1895 by Samuel Hubbard Scudder, based on observations of the species Timema californicum.[2][3][4]

Compared to other stick insects (order Phasmatodea), the genus Timema is considered basal; that is, the earliest "branch" to diverge from the phylogenetic tree that includes all Phasmatodea. To emphasize this outgroup status, all stick insects not included in Timema are sometimes described as "Euphasmatodea."

Five of the twenty-one species of Timema are parthenogenetic, including two species that have not engaged in sexual reproduction for one million years, the longest known asexual period for any insect.[5]

Description

Timema spp. differ from other Phasmatodea in that their tarsi have three segments rather than five. For stick insects, they have relatively small, stout bodies, so that they look somewhat like earwigs (order Dermaptera).[6]

Cryptic coloration and camouflage

Timema walking sticks are night-feeders who spend daytime resting on the leaves or bark of the plants they feed on. Timema colors (primarily green, gray, or brown) and patterns (which may be stripes, scales, or dots) match their typical background, a form of crypsis.[7][8]

In 2008, researchers studying the presence or absence of a dorsal stripe suggested that it has independently evolved several times in Timema species and is an adaptation for crypsis on needle-like leaves. All of the eight Timema species with a dorsal stripe have at least one host plant with needle-like foliage. Of the thirteen unstriped species, seven feed only on broadleaf plants. Four (T. ritense, T. podura, T. genevievae, and T. coffmani) rest during the day on the host plant's trunk rather than its leaves and have bodies that are brown, gray, or tan. Only two species (T. nakipa and T. boharti) have green unstriped morphs that feed on needle-like foliage; both are generalist feeders that also feed on broadleaf hosts.[7]

The species Timema cristinae exhibits both striped and unstriped populations depending on the host plant, a form of polymorphism that clearly illustrates the camouflage function of the stripe.[7] The earliest ancestors of this species were generalists that fed on plants belonging to both the genera Adenostoma and Ceanothus. They eventually diverged into two distinct ecotypes with a more specialist host plant preference. One ecotype prefers to feed on Adenostoma while the other ecotype prefers to feed on Ceanothus. The Adenostoma ecotype possesses a white dorsal stripe, an adaptation to blend in with the needle-like leaves of the plant, while the Ceanothus ecotype does not (Ceanothus spp. have broad leaves). The Adenostoma ecotype is also smaller, with a wider head, and shorter legs.[9]

These characteristics are genetically inherited and has been interpreted as the early stages of the speciation process. The two ecotypes will eventually become separate species once reproductive isolation is achieved. At the moment, both ecotypes are still capable of interbreeding and producing viable offspring, as such they are still considered a single species.[9][10]

Life cycle and reproduction

Timema eggs are soft, ellipsoidal, and about two mm long, with a lid-like structure at one end (the operculum) through which the nymph will emerge.[11] Timema females use particles of dirt, which they have previously ingested, to coat their eggs.[12]

The eggs of many stick insects, including Timema, are attractive to ants, who carry them away to their burrows to feed on the egg's capitulum, while leaving the rest of the egg intact to hatch.[13][14] The emerging nymph passes through six or seven instars before reaching adulthood.[14]

Timema males, in sexual species of Timema, show a consistent pattern of courting behavior. The male climbs onto the back of the female and, after a short display of vibrating and waving, they proceed to mate. (Rejection by the female is possible but uncommon.) The male then rides on the female's back for up to five days, a behavior often referred to as "guarding" the female.[15]

Several species of Timema are parthenogenetic:[16] that is, females can reproduce asexually, producing viable eggs without male participation.

According to Tanja Schwander, "Timema are indeed the oldest insects for which there is good evidence that they have been asexual for long periods of time."[5] She heads a team of researchers who found that five Timema species (T. douglasi, T. monikense, T. shepardi, T. tahoe and T. genevievae) have used only asexual reproduction for more than 500,000 years, with T. tahoe and T. genevievae reproducing asexually for over one million years.[5][17]

Genetic analysis, published in 2023, of four asexual Timema species suggested that males, which are rare but not entirely absent, do in fact engage in sexual reproduction with some females.[18]

Habitat

The geographic range of Timema is limited to mountainous regions of western North America between 30° and 42° N.[16] They are found primarily in California, as well as in a few other neighboring states (Oregon, Nevada, Arizona) and in northern Mexico.[15] All are herbivores, primarily feeding on host plants found in chaparral.[16]

Host plants of the different Timema species include Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas fir), Sequoia sempervirens (Californian redwood), Arctostaphylos spp. (manzanita), Ceanothus spp., Adenostoma fasciculatum (chamise), Abies concolor (white fir), Quercus spp. (oak), Heteromeles arbutifolia (toyon), Cercocarpus spp. (mountain-mahogany), Eriogonum sp. (buckwheat), and Juniperus spp. (juniper).[1]

Phylogeny

General phylogenetic relationships within Timema (Law & Crespi, 2002). Species marked with ♀ are parthenogenetic (female only).[1]

| ← |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification

Timema is the only extant member of the family Timematidae and the suborder Timematodea. Their clade is considered basal to the order Phasmatodea;[11] that is, many scientists believe that Timema-type stick insects represent the earliest "branch" to diverge from the phylogenetic tree that gave rise to all the stick insects of Phasmatodea. This primal distinction is referenced by the name "Euphasmatodea", which is given to all the clades of Phasmatodea other than the suborder Timematodea.[12] While formerly the only member of the family, in 2019 two fossil genera were described from the Cenomanian aged Burmese amber of Myanmar.[19]

Twenty-one species have been described; in addition there are at least two undescribed species known to exist:[7]

- Timema bartmani

- Timema boharti

- Timema californicum

- Timema chumash

- Timema coffmani

- Timema cristinae

- Timema dorotheae

- Timema douglasi

- Timema genevievae

- Timema knulli

- Timema landelsense

- Timema monikense

- Timema morongense

- Timema nakipa

- Timema nevadense

- Timema petita

- Timema podura

- Timema poppense

- Timema ritense

- Timema shepardi

- Timema tahoe

- Timema sp. nov. on limber pine

- Timema sp. nov. on Sargent cypress

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Jennifer H. Law & Bernard J. Crespi (2002). "The evolution of geographic parthenogenesis in Timema walking-sticks". Molecular Ecology (Blackwell Science Ltd.) 11 (8): 1471–1489. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2002.01547.x. PMID 12144667. https://www.sfu.ca/biology/faculty/crespi/pdfs/70-Law-Crespi2002ME.pdf.

- ↑ Brock, P.D. "Species Timema californicum Scudder, 1895". Phasmida Species File Online. http://phasmida.speciesfile.org/Common/basic/Taxa.aspx?TaxonNameID=1004463.

- ↑ Hebard, M. (1920). "The genus Timema Scudder, with the description of a new species, (Orthoptera, Phasmidae, Timeminae)". Entomological News 31: 126–132. http://phasmid-study-group.org/sites/phasmid-study-group.org/files/001845800020198.pdf. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ↑ About Timemas | Timema Discovery Project

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Davies, Ella. "Sticks insects survive one million years without sex". BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/14122050.

- ↑ Borror, Donald J.; Richard E. White (1998). A field guide to insects: America north of Mexico. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 86. ISBN 0-395-91170-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=BkG5T2tg6B4C. "Timema small, stout-bodied, earwig-like forms occurring in the far West"

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Sandoval, Cristina P.; Bernard J. Crespi (2008). "Adaptive evolution of cryptic coloration: the shape of host plants and dorsal stripes in Timema walking-sticks". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 94: 1–5. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00941.x. https://www.sfu.ca/biology/faculty/crespi/pdfs/112-Sandoval&Crespi2008.pdf. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ↑ Gullan, P.J.; P.S. Cranston (2010). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 367. ISBN 978-1-4443-3036-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=zeoq2zfHJGgC. "... many stick insects look very much like sticks and may even move like a twig in the wind."

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lorraine Scanlon (2009). "Timema cristinae". Eukaryon 5: 87–90. http://legacy.lakeforest.edu/images/userImages/eukaryon/Page_7549/p.%2087-90%20Scanlon%20Review.pdf. Retrieved July 22, 2011.

- ↑ Patrik Nosil & Roman Yukilevich (2008). "Mechanisms of reinforcement in natural and simulated polymorphic populations". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 95 (2): 305–319. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01048.x.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Jintsu, Yoshie; Toshiki Uchifune; Ryuchido Machira (2010). "Structural Features of Eggs of the Basal Phasmatodean Timema monikensis Vickery & Sandoval, 1998". Arthropod Systematics & Phylogeny 68 (1): 71–78. http://www.arthropod-systematics.de/ASP_68_1/68_1_Jintsu_71-78.pdf. Retrieved 23 July 2011. "The genus Timema Scudder, 1895 (Timematidae), endemic to western North America, is usually considered the basalmost clade of Phasmatodea, i.e., the sister group of the remaining Phasmatodea".

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Grimaldi, David (2005). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. pp. 213. ISBN 978-0-521-82149-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ql6Jl6wKb88C. Retrieved 23 July 2011. "..the importance of this group is recognized today by its placement into a separate suborder, Timematodea, versus all other families (i.e. the Euphasmatodea)"

- ↑ Hughes, L; M Westoby (1992). "Capitula on stick insect eggs and elaiosomes on seeds: convergent adaptations for burial by ants". Functional Ecology 6 (6): 642–648. doi:10.2307/2389958.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Phasmids". Grzimek’s Animal Life Encyclopedia. http://lemondedesphasmes.free.fr/IMG/pdf/sp657794.pdf.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Arbuthnott, D.; M G Elliot; M A McPeek; B J Crespi (2010). "Divergent patterns of diversification in courtship and genitalic characters of Timema walking-sticks". Journal of Evolutionary Biology 23 (7): 1399–1411. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02000.x. PMID 20456561. https://www.sfu.ca/biology/faculty/crespi/pdfs/Arbuthnottetal2010.pdf. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Crespi, B.J.; C.P. Sandoval (2000). "Phylogenetic evidence for the evolution of ecological specialization in Timema walking-sticks". J. Evol. Biol. 13 (2): 249–262. doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2000.00164.x. http://paradisereserve.ucnrs.org/Docs/j.Evol%20Bio%202000.pdf. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ↑ Schwander, Tanja; Lee Henry; Bernard J Crespi (2011). "Molecular evidence for ancient asexuality in Timema stick insects.". Current Biology 21 (13): 1129–34. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.026. PMID 21683598. https://pure.rug.nl/ws/files/147541304/Molecular_Evidence_for_Ancient_Asexuality_in_Timema_Stick_Insects.pdf.

- ↑ These Male Stick Insects Aren’t ‘Errors’ After All Scientific American

- ↑ Chen, Sha; Deng, Shi‐Wo; Shih, Chungkun; Zhang, Wei‐Wei; Zhang, Peng; Ren, Dong; Zhu, Yi‐Ning; Gao, Tai‐Ping (October 2019). "The earliest Timematids in Burmese amber reveal diverse tarsal pads of stick insects in the mid‐Cretaceous" (in en). Insect Science 26 (5): 945–957. doi:10.1111/1744-7917.12601. ISSN 1672-9609. PMID 29700985. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1744-7917.12601.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q604004 entry

|