Biology:Toolache wallaby

| Toolache wallaby[1] | |

|---|---|

| Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination | |

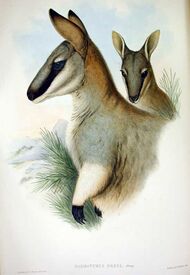

| nineteenth century illustration of male and female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Macropodidae |

| Genus: | Notamacropus |

| Species: | †N. greyi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Notamacropus greyi (Waterhouse, 1846)[3]

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The toolache wallaby or Grey's wallaby (Notamacropus greyi) is an extinct species of wallaby from southeastern South Australia and southwestern Victoria.

Taxonomy

A species described by George Waterhouse in 1846. The type specimen was collected at Coorong in South Australia.[4] The author cites an earlier name, Halmaturus greyii, published by John Edward Gray in 1843 without a valid description, assigning it to a subgenus of the same name—Macropus (Halmaturus)—and providing the common name of the newly described species as Grey's wallaby.[5][6] The common name and epithet greyi commemorates the collector and explorer George Grey, who provided the two specimens to researchers at the British Museum of Natural History.[3] A systematic revision has seen the species placed in a subgeneric arrangement as Macropus (Notamacropus) greyi, recognising an affinity with eight other species of the subgenus named as Notamacropus Dawson and Flannery, 1985.[7] An arrangement that elevates the subgenera of Macropus is recognised as Notamacropus greyi.[8] A genetic analysis found that its closest relative is the western brush wallaby.[9]

The common names have also included monkeyface and onetwo.[6] The name Toolache may come from the Ngarrindjeri word rtulatji.[10]

Description

The toolache wallaby was a slim, graceful, and elegant creature that had a pale ashy-brown pelt with a buff-yellow underbelly.[6][11] The tail was pale grey and became almost white near the tip. The distinct black mark on its face reached from its nose to the eye. The forearms, feet, and tips of the ears were also black. The different colours of the animal also consisted of different textured furs which are believed to have changed seasonally or varied depending on the individual. The body measurements differed between males and females. In general, male toolache wallabies had a head and body length up to 810 mm while females measured up as 840 mm. Despite the females being taller, males had longer tail lengths at about 730 mm while the female's tail length was 710 mm.[12]

Behaviour

The toolache wallaby was a nocturnal animal, foraging for vegetation during the twilight hours of the day.[11] Their movements were unusual and extremely rapid, able to outpace almost any terrestrial predator; they were known to evade the fastest dogs of the colonial hunters.[6]

Habitat

The toolache wallaby occupied the southeastern corner of Australia to the western part of Victoria. The preferred habitat ranged from swampy short grassland areas, to taller grassed areas of the open country. Toolache wallabies were known to be sociable creatures who lived in groups; they were often seen resting and grazing in groups.[12]

Threats

A combination of numerous threats caused the decline and eventual extinction of the toolache wallaby. One of the largest factors was the destruction of its habitat. Since swamps were an important part of its habitat, once they were cleared out, much of the vegetation went with it. Besides the destruction of its habitat, the introduction of predators, such as the European red fox, began to kill off the species as well. Additionally, the animal was also hunted for sport and for its pelt.[12]

Extinction

The toolache wallaby only survived 85 years after European occupation. In the 1920s, a conservation effort was made to try and bring the animal back from the brink of extinction. The plan was to capture and breed the last known surviving members of the species in captivity. This effort ended in disaster after 10 of the 14 of them were accidentally killed in the attempt to capture them. The remaining four survived in captivity.

The last wild sightings were recorded in 1924, and the last known toolache wallaby survived in captivity until 1939.[2] The species is presumed to be extinct, although extensive research is still being conducted in the region after reports of suspected sightings through the 1970s. However, no members of the species have been sighted since.

References

- ↑ Groves, C.P. (2005). Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M.. eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Burbidge, A.A.; Woinarski, J. (2016). "Notamacropus greyi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T12625A128952836. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T12625A21953169.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/12625/128952836. Retrieved 24 April 2023.{{cite iucn}}: error: |doi= / |page= mismatch (help)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Waterhouse, G. R. (1846) (in English). A Natural History of the Mammalia. London: H. Baillière. p. 122. https://archive.org/details/anaturalhistory02wategoog.

- ↑ Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Diprotodontia". in Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 43–70. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=11000259.

- ↑ Green, Tamara (2001). Extinctosaurus: Encyclopedia of Lost and Endangered Species. Brimax. pp. 148. ISBN 9781858543352. OCLC 48178728.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Smith, M.J. (1983). "Complete book of Australian mammals. The national photographic index of Australian wildlife". in Strahan, R.. Complete book of Australian mammals. The national photographic index of Australian wildlife. Angus & Robertson. pp. 234. ISBN 0207144540.

- ↑ Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Diprotodontia". in Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 43–70. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=11000241.

- ↑ Jackson, S.; Groves, C. (2015) (in en). Systematics and taxonomy of Australian mammals. Csiro. p. 158. ISBN 9781486300136. https://books.google.com/books?id=RPznCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA158.

- ↑ Celik, Mélina; Cascini, Manuela; Haouchar, Dalal; Van Der Burg, Chloe; Dodt, William; Evans, Alistair R; Prentis, Peter; Bunce, Michael et al. (2019-06-25). "A molecular and morphometric assessment of the systematics of the Macropus complex clarifies the tempo and mode of kangaroo evolution" (in en). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 186 (3): 793–812. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz005. ISSN 0024-4082. https://academic.oup.com/zoolinnean/article/186/3/793/5421215.

- ↑ "Bringing the Language home: the Ngarrindjeri dictionary project" (in en). Sydney University Press. 2010. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/bitstream/handle/2123/6922/RAL-chapter-32.pdf.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Menkhorst, P.W.; Knight, F. (2011). A field guide to the mammals of Australia (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 9780195573954.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Notamacropus greyi — Toolache Wallaby" (in en). Department of the Environment. https://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=232.

- Flannery, T.; Schouten, P. (2001). A Gap in Nature. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 152. ISBN 0-87113-797-6.

Wikidata ☰ Q109262320 entry

|