Biology:Western gerygone

| Western gerygone | |

|---|---|

| |

| Subspecies exsul | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Acanthizidae |

| Genus: | Gerygone |

| Species: | G. fusca

|

| Binomial name | |

| Gerygone fusca (Gould, 1838)

| |

| Subspecies[2] | |

| |

| |

| Distribution of the western gerygone: Lighter shaded area represents non-breeding migration. | |

The western gerygone (Gerygone fusca) is a small, brownish-grey species of passerine bird, which is found in inland and south-west Australia.[3] It is an arboreal, insectivore of open forest, woodland and dry shrubland.[4] It is not currently threatened with extinction (IUCN: Least Concern).[1]

Systematics and taxonomy

The western gerygone is a member of the family Acanthizidae (Thornbills and Allies), which has been split from the family Pardalotidae (Pardalotes).[5]

It is a sister-species to the mangrove gerygone (Gerygone levigaster).[6] The close relationship of this phylogenetic pair is suggested by analyses of both morphological characteristics[7] and genetic loci.[8] Populations of a common ancestor of the two species are thought to have diverged after becoming fragmented by severe aridity during the Pleistocene.[9] These two species are now in secondary contact in the Carpentarian Basin, but occupy very different habitats and do not interbreed.[9]

The common name western gerygone and scientific name Gerygone fusca are recognized by the taxonomies of the International Ornithological Congress,[2] Clement's Checklist,[10] the Handbook of the Birds of the World[11] and Christidis and Boles.[12]

Description

The western gerygone has plain, brownish-grey upperparts, with no prominent wing markings.[3] The underparts are whitish, with variable amounts of grey on the throat and breast.[3] The outer tail-feathers are conspicuously marked, with large, white patches at the base, a broad, blackish, subterminal tail band and white tips.[13]

It is usually found singly or in pairs,[14] in the mid to upper storey of trees and shrubs[4] and is often located by its characteristic, persistent song.[4] It can be very active when foraging.[15]

The western gerygone is similar in appearance to several other Australian gerygones, which don't usually share its habitat.[16] Its plumage can be distinguished from these species by the diagnostic large, white patches at base of its outer tail feathers.[3]

Distribution

The western gerygone is the most widespread gerygone species and is endemic to Australia.[4] Its three subspecies show subtle differences in plumage and form geographically separate populations:[4]

- Subspecies fusca is found in south-west Western Australia.[10]

- Subspecies exsul is found in eastern Australia; from the Carpentarian Basin, through central and western Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria, and eastern South Australia.[10] An isolated, resident population from the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia is usually ascribed to this subspecies.[17]

- Subspecies mungi is found in central Australia; in the interior of Western Australia, the Northern Territory and South Australia.[10]

Nomadic individuals may travel far beyond this species' regular geographic limits.[17]

Gerygone species are largely allopatric.[16] They are usually separated from each other by their geographic distribution, or by their preference for different habitats.[16] As it is the only gerygone of the Australian interior, the western gerygone does not overlap geographically with other gerygones throughout most of its range.[3]

There are two island populations.[9] Both are near Perth in Western Australia.[9] Rottnest Island was colonized by the western gerygone in the 1950s.[18] It was first observed on the island in 1955 and rapidly spread into all suitable habitat.[19] On nearby Garden Island, which is closer to the Australian mainland, the species has been present since European records began.[9]

Ecology and behaviour

Habitat

The western gerygone occupies a wide range of wooded habitats.[9] These vary from open sclerophyll forests, dominated by a broad array of eucalyptus species, to sparse mallee and mulga shrublands.[9] It is often found along watercourses.[9] In elevated regions, it only occurs below 850 meters.[4]

Movement

Different populations of the western gerygone show different patterns of movement.[9] Those in south-western Western Australia are partial migrants.[9] They breed only in the south-west, but some individuals migrate inland or northwards during winter.[9] Populations in the Carpentarian Basin and on the Eyre Peninsula are sedentary.[9] Desert populations are partially nomadic, responding to inland rainfall.[9]

Foraging

The western gerygone is insectivorous.[4] Its foraging techniques include probing into bark, gleaning from foliage, hovering outside foliage and aerial strikes from perches.[16] It may join other small birds in mixed-species feeding flocks.[15]

Reproduction

Breeding usually occurs between September and January, but has been recorded from August to March.[20] Courtship involves intricate chases between pairs.[4] Territories are maintained throughout the breeding season and territorial disputes involve agitated calls.[4] Males display by intensely fluttering their wings and tail, with their bodies tilted horizontally.[20]

The nest is a long, oval-shaped, pendent structure, with a hooded entrance near the top and a 'tail' at the bottom.[20] Both sexes build the nest.[20]

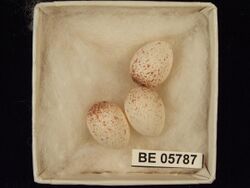

The clutch size is 2 or 3 eggs, (rarely 4).[4] The incubation period lasts 10–12 days, and only the female incubates.[20] The nestling period lasts 10–13 days, and both parents feed the nestlings.[20] Fledglings are fed by their parents for up to 15 days, until independence.[4]

Song

File:Western gerygone mainland song.wav The western gerygone's song is an irregular series of clear, high-pitched whistles, with a meandering melody.[3] Each note maintains a consistent pitch and there is a distinct change in pitch between notes.[19] Although the song isn't loud in volume, its persistence and distinctive tonal qualities are often recognizable from long distances.[4] Singing birds may turn their head in different directions with each note.[4]

Across different mainland populations, songs are fairly similar.[19] Singing is mostly confined to the breeding season and this species is far less conspicuous when it is not breeding.[4]

Song from the colony on Rottnest Island

File:Western gerygone Rottnest Island.wav A distinct, new song has emerged in the western gerygone population which colonized Rottnest Island in the 1950s.[19] Unlike the mainland song, its notes are delivered in a strictly repeated melody.[19] (See sound files on right for comparison.) In 2003, it was estimated that more than a third of the western gerygones on Rottnest island sang the new song, including some individuals which sang both the new song and the typical mainland song.[19]

The island biogeography of birdsong is of interest to evolutionary biologists because of its relevance to speciation.[21] The novel western gerygone song on Rottnest Island is a notable example of both cultural innovation and cultural transmission by social learning.[19] It has occurred over a rapid period of time in a recently isolated population.[19] Sexual selection could eventually result in the typical, mainland western gerygone song on Rottnest Island being completely replaced with the novel song.[19] If secondary contact is subsequently established with the original, mainland population, breeding birds may no longer respond to each other's songs.[19] Behavioural reproductive isolation is a mechanism of evolutionary divergence.[22]

Status, threats and conservation

The western gerygone is common throughout much of its range, especially in Southwest Australia.[13] Extensive clearing of native vegetation in this region has led to a reduction in abundance.[23] Predation of western gerygones by feral cats is thought to be uncommon.[4]

The Australian inland reaches extremely high temperatures in summer.[24] Heat waves in these regions can result in sudden, dramatic, large-scale avian mortality events, with lasting ecological consequences.[24] The frequency of such events is predicted to increase dramatically in coming decades, due to climate change. This poses a threat to Australia's inland birds, potentially including some western gerygone populations.[24]

Despite a declining population trend,[1] the western gerygone's conservation status is categorized as least concern by the IUCN[1] and by most Australian state legislation.[25] This species occupies a wide variety of habitats across a large geographic range,[1] which encompasses numerous protected areas, including large, secure national parks.[26]

Gallery

-

Subspecies fusca.

-

Subspecies exsul.

-

Subspecies mungi.

-

Nest of subspecies exsul. From Emu, 1912[27]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 BirdLife International (2016). "Gerygone fusca". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22704721A93982036. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22704721A93982036.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22704721/93982036. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Gill F, D Donsker & P Rasmussen (Eds). 2020. IOC World Bird List (v10.2). doi : 10.14344/IOC.ML.10.2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Menkhorst, Peter; Rogers, Danny; Clarke, Rohan; Davies, Jeff; Marsack, Peter; Franklin, Kim (2017). The Australian Bird Guide (1st ed.). Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9780643097544.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 Higgins, P.J.; Peter, J.M. (2002). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 6: Pardalotes to Shrike-thrushes.. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. pp. 360–374. ISBN 0-19-553762-9.

- ↑ Winkler, D.W.; Billerman, S.M; Lovette, I.J (2020). Pardalotes (Pardalotidae), version 1.0.. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. doi:10.2173/bow.pardal2.01. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.pardal2.01.

- ↑ Garcia-Navas, Vicente; Rodriguez-Rey, Marta; Marki, Petter Z.; Christidis, Les (2018). "Environmental determinism, and not interspecific competition, drives morphological variability in Australasian warblers (Acanthizidae)". Ecology and Evolution 8 (8): 3871–3882. doi:10.1002/ece3.3925. PMID 29721264.

- ↑ Ford, Julian (1986). "Phylogeny of the Acanthizid Warbler Genus Gerygone Based on Numerical Analyses of Morphological Characters". Emu - Austral Ornithology 86 (1): 12–22. doi:10.1071/MU9860012. https://doi.org/10.1071/MU9860012.

- ↑ Nyari, Arpad S.; Joseph, Leo (2012). "Evolution in Australasian Mangrove Forests: Multilocus Phylogenetic Analysis of the Gerygone Warblers (Aves: Acanthizidae)". PLOS ONE 7 (2): e31840. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031840. PMID 22363748. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...731840N.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 Ford, Julian (1981). "Morphological and Behavioural Evolution in Populations of the Gerygone Fusca Complex". Emu - Austral Ornithology 2 (81): 57–81. doi:10.1071/MU9810057. https://doi.org/10.1071/MU9810057.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Schulenberg, Thomas S.; Iliff, Marshall J.; Billerman, Shawn M.; Sullivan, Brian L.; Wood, Christopher L.; Fredericks, Thomas A. (August 2019). "Clement's Checklist". The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/overview-august-2019/.

- ↑ The Handbook of the Birds of the World.Volume 12: Picathartes to Tits and Chickadees. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. 2008. ISBN 9788496553453.

- ↑ Christidis, Les; Boles, Walter E. (2008). Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds (2nd ed.). Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09602-8.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Pizzey, Graham; Knight, Frank (2003). The Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. Sydney: Harper Collins. ISBN 9780732291938.

- ↑ Chisholm, E. C. (1936). "Birds of the Pilliga Scrub". Emu - Austral Ornithology 36 (1): 32–38. doi:10.1071/MU936032.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Chisholm, E. C. (1938). "The Birds of Barellan, New South Wales With Botanical and Other Notes". Emu - Austral Ornithology 37 (4): 301–313. doi:10.1071/MU937301.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Keast, Allen; Recher, Harry F. (1997). "The Adaptive Zone of the Genus Gerygone (Acanthizidae) as Shown by Morphology and Feeding Habits". Emu - Austral Ornithology 1 (97): 1–17. doi:10.1071/MU97001. https://doi.org/10.1071/MU97001.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Reid, Julian; Brissenden, Piers; Puckridge, Jim; Carpenter, Graham; Paton, Penny (1997). "Comments on the Distribution of Five Bird Species in the Flinders Ranges: Some New Data and a Reappraisal of Historical Records". South Austr. Orn. 32 (7): 113–118.

- ↑ Saunders, D.A.; de Rebeira, C.P. (1985). "Turnover in Breeding Bird Populations on Rottnest I., Western Australia". Wildlife Research 12 (3): 467–77. doi:10.1071/WR9850467.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 Baker, Myron C.; Baker, Merrill S.; Baker, Esther M. (2003). "Rapid evolution of a novel song and an increase in repertoire size in an island population of an Australian songbird". Ibis 145 (465–471): 465–471. doi:10.1046/j.1474-919X.2003.00190.x.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Gregory, P (2020). Western Gerygone (Gerygone fusca) version 1.0. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. doi:10.2173/bow.wesger1.01. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.wesger1.01.

- ↑ Baker, Myron C. (2006). "Differentiation of Mating Vocalizations in Birds: Acoustic Features in Mainland and Island Populations and Evidence of Habitat-Dependent Selection on Songs". Ethology 112 (8): 757–771. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01212.x.

- ↑ Mayr, E. 1963. Animal species and evolution. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- ↑ Masters, J. R.; Milhinch, A. L. (1974). "Birds of the Shire of Northam, About 100 Km East of Perth, Wa". Emu - Austral Ornithology 74 (4): 228–244. doi:10.1071/MU974228.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 McKechnie, Andrew E.; Hockey, Philip A.R.; Blair, O. (2012). "Feeling the heat: Australian landbirds and climate change". Emu - Austral Ornithology 112 (2): i-vii. doi:10.1071/MUv112n2_ED. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/MUv112n2_ED.

- ↑ "Species Lists: Conservation List". https://lists.ala.org.au/public/speciesLists?max=25&sort=listName&order=asc&listType=eq%3ACONSERVATION_LIST&q=&offset=0.

- ↑ "Ownership of protected areas". http://www.environment.gov.au/land/nrs/about-nrs/ownership#levels.

- ↑ Jackson, Sidney Wm. (1912). "Haunts of the Spotted Bower-Bird (Chlamydodera maculata, Gld.)". Emu - Austral Ornithology 12 (2): 65–104. doi:10.1071/MU912065. https://doi.org/10.1071/MU912065.

Wikidata ☰ Q1313727 entry

|

![Nest of subspecies exsul. From Emu, 1912[27]](/wiki/images/thumb/0/07/Emu_volume_12_plate_8.jpg/69px-Emu_volume_12_plate_8.jpg)