Biology:White-winged scoter

| White-winged scoter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult male | |

| |

| Adult female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Melanitta |

| Subgenus: | Melanitta |

| Species: | M. deglandi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Melanitta deglandi (Bonaparte, 1850)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Melanitta fusca deglandi | |

The white-winged scoter (Melanitta deglandi) is a large sea duck. The genus name is derived from Ancient Greek melas "black" and netta "duck". The species name commemorates French ornithologist Côme-Damien Degland.[2]

Description

The white-winged scoter is one of three North American scoter species and the largest species of scoter. Females range from 950 to 1,950 g (2.09 to 4.30 lb) and 48 to 56 cm (19 to 22 in), averaging 1,180 g (2.60 lb) and 52.3 cm (20.6 in). The male ranges from 1,360 to 2,128 g (2.998 to 4.691 lb) and from 53 to 60 cm (21 to 24 in), averaging 1,380 g (3.04 lb) and 55 cm (22 in). The white-winged scoter has a wingspan of 31.5 in (80 cm). This species is characterized by its bulky shape and large bill, which is feathered at the gape unlike the blocky bill base of the surf scoter. The white secondary flight feathers by which the species is named is visible in flight, but may be concealed when swimming.

The male is all black, except for white around the eye and a white speculum. The bill is orange and red with a large black knob at the base. It takes three years for definitive (adult) plumage to be attained – second-year males resemble adult males but exhibit reduced eye markings and have browner flanks. Females are brownish overall and best distinguished from other scoters by the feathered gape and body shape. The facial pattern in female-type birds is highly variable – younger individuals have conspicuous white spots in front and behind the eye, while adults may lack these patches and appear entirely chocolate brown in winter.[3] Juveniles resemble females but have more distinct facial patches and a mottled white belly. The greater secondary coverts of juvenile males have more extensive white than juvenile females which exhibit little to no white fringing.

There are a number of differing characteristics of the Stejneger's scoter and the white-winged scoter. Males of the white-winged scoter have browner flanks, dark yellow coloration of most of the bill and a less tall bill knob, approaching the velvet scoter. The male Stejneger's scoter has a very tall knob at the base of its mostly orange-yellow bill. Female of both species are very similar and best distinguished by head shape; White-winged Scoters tend to have "two-stepped" profile between the bill and the head, compared to the long "Roman nose" profile of Stejneger's Scoter similar to that of a common eider.[4] Additionally, the feathering along the base of the upper mandible forms a right angle on the White-winged scoter, compared to the acute angle on the Stejneger's Scoter.[5]

The Latin binomial commemorates the French zoologist Dr. Côme-Damien Degland (1787–1856).

Taxonomy

It was formerly considered to be conspecific with the velvet scoter, and some taxonomists still regard it as so. These two species, the Stejneger's scoter, and the surf scoter, are placed in the subgenus Melanitta, distinct from the subgenus Oidemia, black and common scoters. Stejneger's scoter was suggested to be a full species, according to a new study.[6]

Birds in Alaska are sometimes recognized as a distinct subspecies, M. d. dixoni, which is reported to have shorter and broader bills on average, but most authorities consider these differences insufficient to warrant taxonomic distinction.[5]

Distribution

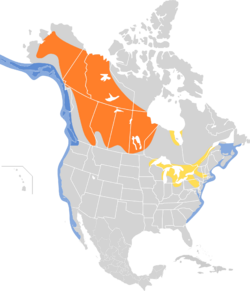

White-winged Scoters have the largest breeding range among North American scoters.[3] They mainly breed in boreal forest from Alaska to Western Canada and are less common east towards the Hudson Bay and south towards the Canadian Prairies. It winters further south in temperate zones, on the Great Lakes, the coasts of the northern United States and the southern coasts of Canada.. It forms large flocks on suitable coastal waters. These are tightly packed, and the birds tend to take off together. It has occurred as a vagrant in Europe, including Scotland,[7] Iceland,[8] Norway and Ireland,[4]

Behavior

Breeding

White-winged Scoters are monogamous and form pairs in late summer, suggesting long-term pair bonds. Their earliest breeding age is two years old. Some adults do not breed annually and gather on large lakes and marshes over summer.

The lined nest is built on the ground close to the sea, lakes or rivers, in woodland or tundra. Five to eleven eggs are laid. The pinkish eggs average 46.9 mm (1.85 in) in breadth, 68.2 mm (2.69 in) in length and 82.4 g (2.91 oz) in weight. The incubation period can range from 25 to 30 days. Males remain with females during the egg-laying period, and typically gather in small groups before leaving the breeding grounds when the young have hatched.[9] After about 21 days, neighboring females may start to behave aggressively towards other nesting females, resulting in confusion and mixing of broods. By the time she is done brooding, a female may be tending to as much as 40 offspring due to the mixing from these conflicts. The female will tend to her brood for up to three weeks and then abandon them, but the young will usually stay together from another three weeks. Brood amalgamation is not uncommon in areas in densely populated breeding grounds, with as many as 100 ducklings gathering in a creche,.[3] Flight capacity is thought to be gained at 63 to 77 days of age.[10]

Diet

White-winged scoters are benthic feeders and forage in open water diving between 5 and 20 m in wintering grounds and 1 and 3 m on breeding grounds. Their large size enables them to find larger prey and dive deeper than Surf or Black Scoters.[3] In freshwater, this species primarily feeds on crustaceans and insects; while in saltwater areas, it feeds on molluscs and crustaceans. Their gizzards, which forms 8% of their body mass, are capable of crushing hard-shelled molluscs.[3] The favorite foods are an amphipod (Hyalella azteca) in freshwater, and rock clams (Protothaca staminea), Atlantic razor clams (Siliqua spp.), and Arctic wedge clams (Mesodesma arctatum).

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2018). "Melanitta deglandi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22734194A132663794. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22734194A132663794.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22734194/132663794. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 132, 246. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. https://archive.org/details/Helm_Dictionary_of_Scientific_Bird_Names_by_James_A._Jobling.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Baldassarre, Guy A. (2014). Ducks, geese, and swans of North America. 2 (2 ed.). Baltimore. ISBN 978-1-4214-0751-7. OCLC 810772720. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/810772720.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Martin Garner (2014). "Velvet, White-winged and Stejneger's Scoters: A Photographic Guide". Birdwatch. https://www.birdguides-cdn.com/cdn/LegacyBirdwatchArticles/velvet%20and%20white-winged%20scoters%20id%20photo%20guide_birdwatchfeb14lr.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Reeber, Sébastien (2015). Waterfowl of North America, Europe, and Asia : an identification guide. Princeton, NJ. ISBN 978-0-691-16266-9. OCLC 927363728. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/927363728.

- ↑ Del Hoyo, Josep; Collar, Nigel; Kirwan, Guy M. (4 March 2020). "Siberian Scoter (Melanitta stejnegeri)". Birds of the World. http://www.hbw.com/species/siberian-scoter-melanitta-stejnegeri.

- ↑ "Changes to the British List". British Ornithologists' Union. 5 December 2013. https://www.bou.org.uk/british-list/recent-announcements/changes/.

- ↑ "American White-winged Scoters in Iceland". The Icelandic Birding Pages. Gunnlaugur Pétursson / Yann Kolbeinsson. https://notendur.hi.is/yannk/status_meldeg.html.

- ↑ Johnsgard, Paul A. (2016). The North American sea ducks : their biology and behavior. Zea E-Books. Lincoln, Nebraska. ISBN 978-1-60962-106-3. OCLC 964451715. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/964451715.

- ↑ Hochbaum, H. Albert (1944). The Canvasback on a Prairie Marsh. ISBN 978-1127552931.

External links

- BirdLife species factsheet for Melanitta deglandi

- "Melanitta deglandi". Avibase. https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?lang=EN&avibaseid=.

- "White-winged scoter media". Internet Bird Collection. http://www.hbw.com/ibc/species/white-winged-scoter-melanitta-fusca.

- White-winged scoter photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- White-winged Scoter Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Wikidata ☰ Q2020137 entry

|