Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture

In mathematics, the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture (often called the Birch–Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture) describes the set of rational solutions to equations defining an elliptic curve. It is an open problem in the field of number theory and is widely recognized as one of the most challenging mathematical problems. It is named after mathematicians Bryan John Birch and Peter Swinnerton-Dyer, who developed the conjecture during the first half of the 1960s with the help of machine computation. (As of 2023), only special cases of the conjecture have been proven.

The modern formulation of the conjecture relates arithmetic data associated with an elliptic curve E over a number field K to the behavior of the Hasse–Weil L-function L(E, s) of E at s = 1. More specifically, it is conjectured that the rank of the abelian group E(K) of points of E is the order of the zero of L(E, s) at s = 1, and the first non-zero coefficient in the Taylor expansion of L(E, s) at s = 1 is given by more refined arithmetic data attached to E over K (Wiles 2006).

The conjecture was chosen as one of the seven Millennium Prize Problems listed by the Clay Mathematics Institute, which has offered a $1,000,000 prize for the first correct proof.[1]

Background

(Mordell 1922) proved Mordell's theorem: the group of rational points on an elliptic curve has a finite basis. This means that for any elliptic curve there is a finite subset of the rational points on the curve, from which all further rational points may be generated.

If the number of rational points on a curve is infinite then some point in a finite basis must have infinite order. The number of independent basis points with infinite order is called the rank of the curve, and is an important invariant property of an elliptic curve.

If the rank of an elliptic curve is 0, then the curve has only a finite number of rational points. On the other hand, if the rank of the curve is greater than 0, then the curve has an infinite number of rational points.

Although Mordell's theorem shows that the rank of an elliptic curve is always finite, it does not give an effective method for calculating the rank of every curve. The rank of certain elliptic curves can be calculated using numerical methods but (in the current state of knowledge) it is unknown if these methods handle all curves.

An L-function L(E, s) can be defined for an elliptic curve E by constructing an Euler product from the number of points on the curve modulo each prime p. This L-function is analogous to the Riemann zeta function and the Dirichlet L-series that is defined for a binary quadratic form. It is a special case of a Hasse–Weil L-function.

The natural definition of L(E, s) only converges for values of s in the complex plane with Re(s) > 3/2. Helmut Hasse conjectured that L(E, s) could be extended by analytic continuation to the whole complex plane. This conjecture was first proved by (Deuring 1941) for elliptic curves with complex multiplication. It was subsequently shown to be true for all elliptic curves over Q, as a consequence of the modularity theorem in 2001.

Finding rational points on a general elliptic curve is a difficult problem. Finding the points on an elliptic curve modulo a given prime p is conceptually straightforward, as there are only a finite number of possibilities to check. However, for large primes it is computationally intensive.

History

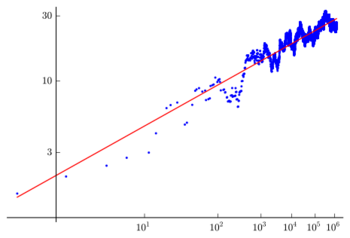

In the early 1960s Peter Swinnerton-Dyer used the EDSAC-2 computer at the University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory to calculate the number of points modulo p (denoted by Np) for a large number of primes p on elliptic curves whose rank was known. From these numerical results (Birch Swinnerton-Dyer) conjectured that Np for a curve E with rank r obeys an asymptotic law

- [math]\displaystyle{ \prod_{p\leq x} \frac{N_p}{p} \approx C\log (x)^r \mbox{ as } x \rightarrow \infty }[/math]

where C is a constant.

Initially, this was based on somewhat tenuous trends in graphical plots; this induced a measure of skepticism in J. W. S. Cassels (Birch's Ph.D. advisor).[2] Over time the numerical evidence stacked up.

This in turn led them to make a general conjecture about the behavior of a curve's L-function L(E, s) at s = 1, namely that it would have a zero of order r at this point. This was a far-sighted conjecture for the time, given that the analytic continuation of L(E, s) was only established for curves with complex multiplication, which were also the main source of numerical examples. (NB that the reciprocal of the L-function is from some points of view a more natural object of study; on occasion, this means that one should consider poles rather than zeroes.)

The conjecture was subsequently extended to include the prediction of the precise leading Taylor coefficient of the L-function at s = 1. It is conjecturally given by[3]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{L^{(r)}(E,1)}{r!} = \frac{\#\mathrm{Sha}(E)\Omega_E R_E \prod_{p|N}c_p}{(\#E_{\mathrm{Tor}})^2} }[/math]

where the quantities on the right-hand side are invariants of the curve, studied by Cassels, Tate, Shafarevich and others (Wiles 2006):

[math]\displaystyle{ \#E_{\mathrm{Tor}} }[/math] is the order of the torsion group,

[math]\displaystyle{ \#\mathrm{Sha}(E) }[/math] is the order of the Tate–Shafarevich group,

[math]\displaystyle{ \Omega_E }[/math] is the real period of E multiplied by the number of connected components of E,

[math]\displaystyle{ R_E }[/math] is the regulator of E which is defined via the canonical heights of a basis of rational points,

[math]\displaystyle{ c_p }[/math] is the Tamagawa number of E at a prime p dividing the conductor N of E. It can be found by Tate's algorithm.

Current status

The Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture has been proved only in special cases:

- (Coates Wiles) proved that if E is a curve over a number field F with complex multiplication by an imaginary quadratic field K of class number 1, F = K or Q, and L(E, 1) is not 0 then E(F) is a finite group. This was extended to the case where F is any finite abelian extension of K by (Arthaud 1978).

- (Gross Zagier) showed that if a modular elliptic curve has a first-order zero at s = 1 then it has a rational point of infinite order; see Gross–Zagier theorem.

- (Kolyvagin 1989) showed that a modular elliptic curve E for which L(E, 1) is not zero has rank 0, and a modular elliptic curve E for which L(E, 1) has a first-order zero at s = 1 has rank 1.

- (Rubin 1991) showed that for elliptic curves defined over an imaginary quadratic field K with complex multiplication by K, if the L-series of the elliptic curve was not zero at s = 1, then the p-part of the Tate–Shafarevich group had the order predicted by the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture, for all primes p > 7.

- (Breuil Conrad), extending work of (Wiles 1995), proved that all elliptic curves defined over the rational numbers are modular, which extends results #2 and #3 to all elliptic curves over the rationals, and shows that the L-functions of all elliptic curves over Q are defined at s = 1.

- (Bhargava Shankar) proved that the average rank of the Mordell–Weil group of an elliptic curve over Q is bounded above by 7/6. Combining this with the p-parity theorem of (Nekovář 2009) and (Dokchitser Dokchitser) and with the proof of the main conjecture of Iwasawa theory for GL(2) by (Skinner Urban), they conclude that a positive proportion of elliptic curves over Q have analytic rank zero, and hence, by (Kolyvagin 1989), satisfy the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture.

There are currently no proofs involving curves with a rank greater than 1.

There is extensive numerical evidence for the truth of the conjecture.[4]

Consequences

Much like the Riemann hypothesis, this conjecture has multiple consequences, including the following two:

- Let n be an odd square-free integer. Assuming the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture, n is the area of a right triangle with rational side lengths (a congruent number) if and only if the number of triplets of integers (x, y, z) satisfying 2x2 + y2 + 8z2 = n is twice the number of triplets satisfying 2x2 + y2 + 32z2 = n. This statement, due to Tunnell's theorem (Tunnell 1983), is related to the fact that n is a congruent number if and only if the elliptic curve y2 = x3 − n2x has a rational point of infinite order (thus, under the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer conjecture, its L-function has a zero at 1). The interest in this statement is that the condition is easily verified.[5]

- In a different direction, certain analytic methods allow for an estimation of the order of zero in the center of the critical strip of families of L-functions. Admitting the BSD conjecture, these estimations correspond to information about the rank of families of elliptic curves in question. For example: suppose the generalized Riemann hypothesis and the BSD conjecture, the average rank of curves given by y2 = x3 + ax+ b is smaller than 2.[6]

Notes

- ↑ Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture at Clay Mathematics Institute

- ↑ Stewart, Ian (2013), Visions of Infinity: The Great Mathematical Problems, Basic Books, p. 253, ISBN 9780465022403, https://books.google.com/books?id=dzdSy3diraUC&pg=PA253, "Cassels was highly skeptical at first".

- ↑ Cremona, John (2011). "Numerical evidence for the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture". Talk at the BSD 50th Anniversary Conference, May 2011. https://people.maths.bris.ac.uk/~matyd/BSD2011/bsd2011-Cremona.pdf., page 50

- ↑ Cremona, John (2011). "Numerical evidence for the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture". Talk at the BSD 50th Anniversary Conference, May 2011. https://people.maths.bris.ac.uk/~matyd/BSD2011/bsd2011-Cremona.pdf.

- ↑ Introduction to Elliptic Curves and Modular Forms. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 97 (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. 1993. ISBN 0-387-97966-2.

- ↑ Heath-Brown, D. R. (2004). "The Average Analytic Rank of Elliptic Curves". Duke Mathematical Journal 122 (3): 591–623. doi:10.1215/S0012-7094-04-12235-3.

References

- Arthaud, Nicole (1978). "On Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer's conjecture for elliptic curves with complex multiplication". Compositio Mathematica 37 (2): 209–232.

- Bhargava, Manjul; Shankar, Arul (2015). "Ternary cubic forms having bounded invariants, and the existence of a positive proportion of elliptic curves having rank 0". Annals of Mathematics 181 (2): 587–621. doi:10.4007/annals.2015.181.2.4.

- Birch, Bryan; Swinnerton-Dyer, Peter (1965). "Notes on Elliptic Curves (II)". J. Reine Angew. Math. 165 (218): 79–108. doi:10.1515/crll.1965.218.79.

- Breuil, Christophe; Conrad, Brian; Diamond, Fred; Taylor, Richard (2001). "On the Modularity of Elliptic Curves over Q: Wild 3-Adic Exercises". Journal of the American Mathematical Society 14 (4): 843–939. doi:10.1090/S0894-0347-01-00370-8.

- Coates, J.H.; Greenberg, R.; Ribet, K.A.; Rubin, K. (1999). Arithmetic Theory of Elliptic Curves. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. 1716. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-66546-3.

- Coates, J.; Wiles, A. (1977). "On the conjecture of Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer". Inventiones Mathematicae 39 (3): 223–251. doi:10.1007/BF01402975. Bibcode: 1977InMat..39..223C.

- Deuring, Max (1941). "Die Typen der Multiplikatorenringe elliptischer Funktionenkörper". Abhandlungen aus dem Mathematischen Seminar der Universität Hamburg 14 (1): 197–272. doi:10.1007/BF02940746.

- Dokchitser, Tim; Dokchitser, Vladimir (2010). "On the Birch–Swinnerton-Dyer quotients modulo squares". Annals of Mathematics 172 (1): 567–596. doi:10.4007/annals.2010.172.567.

- Gross, Benedict H.; Zagier, Don B. (1986). "Heegner points and derivatives of L-series". Inventiones Mathematicae 84 (2): 225–320. doi:10.1007/BF01388809. Bibcode: 1986InMat..84..225G.

- Kolyvagin, Victor (1989). "Finiteness of E(Q) and X(E, Q) for a class of Weil curves". Math. USSR Izv. 32 (3): 523–541. doi:10.1070/im1989v032n03abeh000779. Bibcode: 1989IzMat..32..523K.

- Mordell, Louis (1922). "On the rational solutions of the indeterminate equations of the third and fourth degrees". Proc. Camb. Phil. Soc. 21: 179–192.

- Nekovář, Jan (2009). "On the parity of ranks of Selmer groups IV". Compositio Mathematica 145 (6): 1351–1359. doi:10.1112/S0010437X09003959.

- Rubin, Karl (1991). "The 'main conjectures' of Iwasawa theory for imaginary quadratic fields". Inventiones Mathematicae 103 (1): 25–68. doi:10.1007/BF01239508. Bibcode: 1991InMat.103...25R.

- Skinner, Christopher; Urban, Éric (2014). "The Iwasawa main conjectures for GL2". Inventiones Mathematicae 195 (1): 1–277. doi:10.1007/s00222-013-0448-1. Bibcode: 2014InMat.195....1S.

- Tunnell, Jerrold B. (1983). "A classical Diophantine problem and modular forms of weight 3/2". Inventiones Mathematicae 72 (2): 323–334. doi:10.1007/BF01389327. Bibcode: 1983InMat..72..323T. http://dml.cz/bitstream/handle/10338.dmlcz/137483/ActaOstrav_14-2006-1_8.pdf.

- Wiles, Andrew (1995). "Modular elliptic curves and Fermat's last theorem". Annals of Mathematics. Second Series 141 (3): 443–551. doi:10.2307/2118559. ISSN 0003-486X.

- Wiles, Andrew (2006). "The Millennium prize problems". in Carlson, James; Jaffe, Arthur; Wiles, Andrew. The Millennium prize problems. American Mathematical Society. pp. 31–44. ISBN 978-0-8218-3679-8. http://www.claymath.org/sites/default/files/birchswin.pdf. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/Swinnerton-DyerConjecture.html.

- "Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture". http://planetmath.org/?op=getobj&from=objects&id={{{id}}}.

- The Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture: An Interview with Professor Henri Darmon by Agnes F. Beaudry

- What is the Birch and Swinnerton-Dyer Conjecture? lecture by Manjul Bhargava (september 2016) given during the Clay Research Conference held at the University of Oxford

|