Caribbean amber

Caribbean amber is amber found in the Caribbean area (Dominican Republic and Colombia). Resin from the extinct tree Hymenaea protera is the source of Caribbean amber and probably of most amber found in the tropics.

Caribbean amber differentiates itself from Baltic amber by being nearly always transparent, and it has a higher number of fossil inclusions. This has enabled the detailed reconstruction of the ecosystem of a long-vanished tropical forest.[1]

Age

A study in the early 1990s returned a date up to 40 million years old for Dominican Amber.[2] However, according to Poinar,[3] Dominican amber dates from Oligocene to Miocene, thus about 25 million years old. The oldest, and hardest of this amber comes from the mountain region north of Santiago. The La Cumbre, La Toca, Palo Quemado, La Bucara, and Los Cacaos mining sites in the Cordillera Septentrional not far from Santiago.[4] Amber has also been found in the south-eastern Bayaguana/Sabana de la Mar area.[5]| Colombian Amber is much younger than Dominican amber and is therefore considered copal by many.[6] Colombian copal is the subfossil resins of leguminous trees of the genus Hymenaea sp. (Fabaceae)[7] Interestingly, the spectra of the copals from East Africa and Colombia are almost entirely super imposable and are very similar to the spectra of Baltic amber from North Germany, with the bands characteristic of labdane compounds observed in each. [8]Currently, it is also used in professional jewelry often sold as "Green Caribbean Amber".

Amber from the Caribbean

Caribbean amber, especially Dominican blue amber, is mined through bell pitting, which is extremely dangerous. The bell pit is basically a foxhole dug with whatever tools are available. Machetes do the start, some shovels, picks and hammers may participate eventually. The pit itself goes as deep or safe as possible, sometimes vertical, sometimes horizontal, but never level. It snakes into hill sides, drops away, joins up with others, goes straight up and pops out elsewhere. 'Foxhole' applies indeed: rarely are the pits large enough to stand in, and then only at the entrance. Miners crawl around on their knees using short-handled picks, shovels and machetes.

There are little to no safety measures. A pillar or so may hold back the ceiling from time to time but only if the area has previously collapsed. Candles are the only source of light. Humidity inside the mines is at 100%. Since the holes are situated high on mountainsides and deep inside said mountains, the temperature is cool and bearable, but after several hours the air becomes stale. During rain the mines are forced to close. The holes fill up quickly with water, and there is little point in pumping it out again (although sometimes this is done) because the unsecured walls may crumble.[9]

Colors

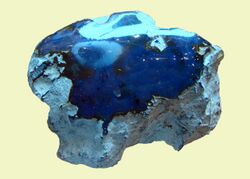

Caribbean amber can be found in many colors, besides the obvious amber. Yellow and honey colored are fairly common. There is also red and green in smaller quantities and the rare blue amber (fluorescent).[10][11]

The blue amber reportedly is found mostly in Palo Quemado mine, in the Pescado Bobo mine south from La Cumbre but also in the southern part of the Dominican Republic, like in the mines around the town El Valle. The amber found in the later is probably younger than the amber found in the north.

The Museo del Ambar Dominicano, in Puerto Plata, as well as the Amber World Museum in Santo Domingo have collections of amber specimens.[12]

See also

- Lagerstätte

- Baltic Amber

References

- ↑ George Poinar, Jr. and Roberta Poinar, 1999. The Amber Forest: A Reconstruction of a Vanished World, (Princeton University Press) ISBN 0-691-02888-5

- ↑ Browne, Malcolm W. (1992-09-25). "40-Million-Year-Old Extinct Bee Yields Oldest Genetic Material". New York Times. https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=health&res=9E0CE2DD123BF936A1575AC0A964958260. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ↑ George Poinar, Jr. and Roberta Poinar, 1999. The Amber Forest: A Reconstruction of a Vanished World, (Princeton University Press) ISBN 0-691-02888-5

- ↑ Corday, Alec (2006). "Dominican Amber Mines: The Definitive List". The Blue Amber Blog. Archived from the original on 2008-04-20. https://web.archive.org/web/20080420083549/http://ambarazul.com/wordpress/2006/09/. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ↑ Schlee, D. (1984): Notizen über einige Bernsteine und Kopale aus aller Welt. Stuttgarter Beitr. Naturk. Ser. C, 18: 29-47, page 35

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://ambermuseum.eu/en/news/item/172-bursztyn-baltycki-vs-kopal-kolumbijski/. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0120-04882017000100085/. | by GEORGE POINAR JR., ANDRIS BUKEJS, ANDREI A. LEGALOV - ↑ Article in Spectrochimica Acta Part A Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, Spectrochimica Acta Part A Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy · June 2001

- ↑ Martínez, R. & Schlee, D. (1984): Die Dominikanischen Bernsteinminen der Nordkordillera, speziell auch aus der Sicht der Werkstaetten. – Stuttgarter Beitr. Naturk., C, 18: 79-84; Stuttgart.

- ↑ Schlee, D. (1980): Bernstein-Raritaeten (Farben, Strukturen, Fossilen, Handwerk). – 88 S. (mit 55 Farbtafeln); Staatl. Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart.

- ↑ L. Linati and D. Sacchi, V. Bellani, E. Giulotto (2005). "The origin of the blue fluorescence in Dominican amber". J. Appl. Phys. 97: 016101. doi:10.1063/1.1829395.

- ↑ Penny, D. (2010). "Chapter 2: Dominican Amber". in Penney, D.. Biodiversity of Fossils in Amber from the Major World Deposits. Siri Scientific Press. pp. 167–191. ISBN 978-0-9558636-4-6.