Chemistry:AI-10-49

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| |

| CAS Number | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

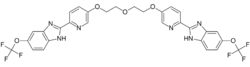

| Formula | C30H22F6N6O5 |

| Molar mass | 660.533 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

AI-10-49 is a small molecule inhibitor of leukemic oncoprotein CBFβ-SMHHC developed by the laboratory of John Bushweller (University of Virginia) with efficacy demonstrated by the laboratories of Lucio H. Castilla (University of Massachusetts Medical School) and Monica Guzman (Cornell University).[1][2][3][4] AI-10-49 allosterically binds to CBFβ-SMMHC and disrupts protein-protein interaction between CBFβ-SMMHC and tumor suppressor RUNX1. This inhibitor is under development as an anti-leukemic drug.

Core binding factors

Core-binding factor (CBF) is a heterodimeric transcription factor composed by the CBFβ and RUNX subunits (the latter is encoded by RUNX1, RUNX2, or RUNX3 genes). CBF plays critical roles in most hematopoietic lineages, regulating gene expression of a variety of genes associated with cell cycle, differentiation, signaling and adhesion.[5] In hematopoiesis, CBF regulates progenitor cell fate decisions and differentiation at multiple levels. The function of CBF is essential for the emergence of embryonic hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and establishment of definitive hematopoiesis at midgestation.[6][7][8] Similarly, in adult hematopoiesis, CBF regulates the frequency and differentiation of HSCs, lymphoid and myeloid progenitors,[9][10] establishing CBF as a master regulator of hematopoietic homeostasis.

Core binding factors and leukemia

CBF members are frequent targets of mutations and rearrangements in human leukemia. Point-mutations in RUNX1 gene have been reported in patients with familial platelet disorder, myeloid dysplastic syndrome, and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.[11][12] In addition, RUNX1 mutations have also been reported in Acute myeloid leukemia (AML).[13] The RUNX1 and CBFB genes are targets of chromosome rearrangements that create oncogenic fusion genes in leukemia. The chromosome translocation t(12;21) (p13.1;q22) causes the fusion of the ETS variant 6 (ETV6) and RUNX1 genes results in ETV6-RUNX1 gene fusion and is the most common genetic aberration in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).[14] The "core binding factor AML" (CBF AML) [WHO classification] is the most common group of AML, including groups with the chromosome rearrangements inv(16)(p13q22) and t(8;21)(q22;q22). The chromosome translocation t(8;21)(q22;q22) creates the RUNX1-ETO fusion gene, which is expressed in FAB subtype M2 AML samples.[15] The pericentric chromosome inversion inv(16)(p13q22) creates the CBFB-MYH11 fusion gene, which encodes the CBFβ-SMMHC fusion protein.[16][17]

Inv(16) leukemia

The inv(16) is present in all M4Eo subtype AML, representing one of the most common change in AML, and accounting for ≈12% of de novo human AML.[18] Studies by various laboratories have established that CBFβ-SMMHC acts as a dominant repressor of CBF function in vivo and specifically blocks lymphoid and myeloid lineage differentiation.[19][20][21][22]

Treatment of AML varies based on the prognosis and mutations identified in the patient sample. Current treatment for inv(16) AML uses chemotherapy drugs, such as doxorubicin and cytarabine, with an estimated 5-year overall survival of 60% in young patients and only 20% in the elderly.[23][24]

Discovery

CBFβ-SMMHC outcompetes CBFβ for binding to RUNX1 by direct protein-protein interaction.[25][26][27]

Using a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) based assay, AI-4-57 was discovered as the lead compound which can inhibit CBFβ-SMHHC –RUNX1 protein-protein interaction.[1] To get good in vivo pharmacokinetics, selectivity and potency AI-10-49 was developed which has a seven atom polyethylene glycol-based linker and a trifluoromethoxy substitution. This molecule releases RUNX1 from CBFβ-SMHHC specifically and restores the RUNX1 transcriptional program in inv(16) positive human leukemic cells. Viability assays showed AI-10-49 has an IC50 of 0.6μM. Pharmacokinetic studies showed that AI-10-49 has half-life of 380 minutes in mouse plasma. AI-10-49 prolonged the survival of mice transplanted with CBFβ-SMHHC leukemic cells without any signs of toxicity. AI-10-49 reduced viability and colony forming ability of human primary inv(16) leukemic blast cells, without affecting normal human bone marrow cells as wells non- inv(16) primary human leukemic blast cells. Overall, these findings validate inhibition of RUNX1- CBFβ-SMMHC protein-protein interaction as a novel therapeutic avenue for leukemia with inv(16) and AI-10-49 as a specific inhibitor of CBFβ-SMHHC oncoprotein. The discovery of AI-10-49 provides additional evidence that transcription factor drivers of cancer can be directly targeted. AI-10-49 belongs to a select group of protein-protein interaction inhibitors that has been shown to have specific and potent efficiency without toxicity in cancer therapy.[citation needed]

Mechanism of action of AI-10-49

The mechanism of action of AI-10-49 was recently elucidated by the Castilla laboratory at University of Massachusetts Medical School.[28][29][30][31] Gene Set Enrichment Analysis of RNA-seq data from inv(16) AML cells treated with AI-10-49 identified the deregulation of a MYC signature, including cell cycle, ribosome biogenesis and metabolism. MYC shRNA knockdown induced apoptosis of inv(16) AML cells, and MYC overexpression partially rescued AI-10-49 induced apoptosis. Furthermore, mouse leukemia cells transduced with Myc shRNAs showed significant delay in leukemic latency upon transplantation, validating the requirement of MYC in inv(16) AML maintenance in vivo. Pharmacologic inhibition of MYC activity, using a combined treatment with AI-10-49 and the BET-family bromodomain inhibitor JQ1, revealed a strong synergy in inv(16) AML cells and a significant delay in leukemia latency in mice. ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq analysis revealed that inhibition of the CBFβ-SMHHC–RUNX1 protein–protein interaction by AI-10-49 results in increased RUNX1 occupancy at three MYC distal enhancers downstream from MYC transcription start site. Deletion of the RUNX1 binding site in these enhancers by genome editing (CRISPR/Cas9) reduced MYC transcript levels and the viability of inv(16) AML cells, indicating that each one of these enhancers plays a critical role in regulating MYC levels and sustaining the survival of inv(16) AML cells. Analysis of enhancer-promoter interactions by chromosome conformation capture carbon copy (5C) in inv(16) AML cells revealed that the three enhancers are physically connected with each other and to the MYC promoter. Analysis of chromatin immunoprecipitation revealed that AI-10-49 treatment results in the displacement of the SWI/SNF complex component BRG1 and RUNX1 mediated recruitment of polycomb-repressive complex 1 (PRC1) component RING1B at the three MYC enhancers. Taken together, these results demonstrate that AI-10-49 treatment induces an acute release of RUNX1, increases RUNX1 occupancy at MYC enhancers, and disrupts enhancer chromatin dynamics which in turn induces apoptosis by repressing MYC. Furthermore, this study suggests that combined treatment of inv(16) AML with AI-10-49 and BET-family inhibitors may represent a promising targeted therapy.[citation needed]

Protein-protein interaction inhibitors in cancer therapy

Targeting protein-protein interaction with small molecule is known to be extremely difficult due to the fact that binding regions consist of wide, shallow surfaces.[32] There are few protein-protein interaction inhibitors with specific and non-toxic effect in various cancer types. The first and best characterized protein-protein interaction inhibitor in cancer therapy is Nutlin.[33] Nutlin inhibits the interaction between HDM2 and tumour suppressor p53. After the discovery of Nutlin, more than 20 small molecule inhibitors have been developed by academic institutes and pharmaceutical companies of which 8 inhibitors are under Phase 1 clinical trials.[34] Other examples for protein-protein interaction inhibitors include JQ1 (inhibits the interaction between acetylated histones and BRD4);[35] 79-6 (inhibits BCL6 BTB domain dimerization);[36] MI-463 and MI-503 (inhibit Menin-MLL interaction)[37] and ABT-737 (inhibits BCL2L1-BCL2 interaction).[38]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Chemical biology. A small-molecule inhibitor of the aberrant transcription factor CBFβ-SMMHC delays leukemia in mice". Science 347 (6223): 779–784. February 2015. doi:10.1126/science.aaa0314. PMID 25678665.

- ↑ "Drug discovery. Tying up a transcription factor". Science (New York, N.Y.) 347 (6223): 713–4. February 2015. doi:10.1126/science.aaa6119. PMID 25678644.

- ↑ "Free RUNX1.". Nature Chemical Biology 11 (4): 241. April 2015. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1784.

- ↑ "Selective inhibition of the leukemia fusion protein CBFβ-SMMHC by small molecule AI-10-49 in the treatment of Inv (16) AML.". Blood 124 (21): 390. November 2014. doi:10.1182/blood.V124.21.390.390.

- ↑ "The RUNX genes: gain or loss of function in cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer 5 (5): 376–87. May 2005. doi:10.1038/nrc1607. PMID 15864279.

- ↑ "AML1, the target of multiple chromosomal translocations in human leukemia, is essential for normal fetal liver hematopoiesis". Cell 84 (2): 321–30. January 1996. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80986-1. PMID 8565077.

- ↑ "Definitive hematopoietic stem cells first develop within the major arterial regions of the mouse embryo". The EMBO Journal 19 (11): 2465–74. June 2000. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.11.2465. PMID 10835345.

- ↑ "Runx1 is required for the endothelial to haematopoietic cell transition but not thereafter". Nature 457 (7231): 887–91. February 2009. doi:10.1038/nature07619. PMID 19129762. Bibcode: 2009Natur.457..887C.

- ↑ "AML-1 is required for megakaryocytic maturation and lymphocytic differentiation, but not for maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells in adult hematopoiesis". Nature Medicine 10 (3): 299–304. March 2004. doi:10.1038/nm997. PMID 14966519.

- ↑ "Loss of Runx1 perturbs adult hematopoiesis and is associated with a myeloproliferative phenotype". Blood 106 (2): 494–504. July 2005. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-08-3280. PMID 15784726.

- ↑ "A novel CBFA2 single-nucleotide mutation in familial platelet disorder with propensity to develop myeloid malignancies". Blood 98 (9): 2856–2858. November 2001. doi:10.1182/blood.v98.9.2856. PMID 11675361.

- ↑ "Haploinsufficiency of CBFA2 causes familial thrombocytopenia with propensity to develop acute myelogenous leukaemia". Nature Genetics 23 (2): 166–175. October 1999. doi:10.1038/13793. PMID 10508512.

- ↑ "Trisomy 13 correlates with RUNX1 mutation and increased FLT3 expression in AML-M0 patients". Haematologica 92 (8): 1123–1126. August 2007. doi:10.3324/haematol.11296. PMID 17650443.

- ↑ "Acute lymphoblastic leukemia". The New England Journal of Medicine 350 (15): 1535–48. April 2004. doi:10.1056/NEJMra023001. PMID 15071128.

- ↑ "Identification of breakpoints in t(8;21) acute myelogenous leukemia and isolation of a fusion transcript, AML1/ETO, with similarity to Drosophila segmentation gene, runt". Blood 80 (7): 1825–1831. October 1992. doi:10.1182/blood.V80.7.1825.1825. PMID 1391946.

- ↑ "Association of an inversion of chromosome 16 with abnormal marrow eosinophils in acute myelomonocytic leukemia. A unique cytogenetic-clinicopathological association". The New England Journal of Medicine 309 (11): 630–636. September 1983. doi:10.1056/NEJM198309153091103. PMID 6577285.

- ↑ "Fusion between transcription factor CBF beta/PEBP2 beta and a myosin heavy chain in acute myeloid leukemia". Science 261 (5124): 1041–1044. August 1993. doi:10.1126/science.8351518. PMID 8351518. Bibcode: 1993Sci...261.1041L.

- ↑ "Oncogenic transcription factors in the human acute leukemias". Science (New York, N.Y.) 278 (5340): 1059–64. November 1997. doi:10.1126/science.278.5340.1059. PMID 9353180.

- ↑ "Failure of embryonic hematopoiesis and lethal hemorrhages in mouse embryos heterozygous for a knocked-in leukemia gene CBFB-MYH11". Cell 87 (4): 687–696. November 1996. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81388-4. PMID 8929537.

- ↑ "The fusion gene Cbfb-MYH11 blocks myeloid differentiation and predisposes mice to acute myelomonocytic leukaemia". Nature Genetics 23 (2): 144–146. October 1999. doi:10.1038/13776. PMID 10508507.

- ↑ "Cbf beta-SMMHC induces distinct abnormal myeloid progenitors able to develop acute myeloid leukemia". Cancer Cell 9 (1): 57–68. January 2006. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2005.12.014. PMID 16413472.

- ↑ "Cbfbeta-SMMHC impairs differentiation of common lymphoid progenitors and reveals an essential role for RUNX in early B-cell development". Blood 111 (3): 1543–1551. February 2008. doi:10.1182/blood-2007-07-104422. PMID 17940206.

- ↑ "Molecular heterogeneity and prognostic biomarkers in adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics". Current Opinion in Hematology 12 (1): 68–75. January 2005. doi:10.1097/01.moh.0000149608.29685.d1. PMID 15604894.

- ↑ "Pretreatment cytogenetics add to other prognostic factors predicting complete remission and long-term outcome in patients 60 years of age or older with acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 8461". Blood 108 (1): 63–73. July 2006. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-11-4354. PMID 16522815.

- ↑ "Altered affinity of CBF beta-SMMHC for Runx1 explains its role in leukemogenesis". Nature Structural Biology 9 (9): 674–9. September 2002. doi:10.1038/nsb831. PMID 12172539.

- ↑ "The leukemic protein core binding factor beta (CBFbeta)-smooth-muscle myosin heavy chain sequesters CBFalpha2 into cytoskeletal filaments and aggregates". Molecular and Cellular Biology 18 (12): 7432–43. December 1998. doi:10.1128/MCB.18.12.7432. PMID 9819429.

- ↑ "Molecular basis for a dominant inactivation of RUNX1/AML1 by the leukemogenic inversion 16 chimera". Blood 103 (8): 3200–7. April 2004. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-07-2188. PMID 15070703.

- ↑ "CBFβ-SMMHC Inhibition Triggers Apoptosis by Disrupting MYC Chromatin Dynamics in Acute Myeloid Leukemia". Cell 174 (1): 172–186.e21. June 2018. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.048. PMID 29958106.

- ↑ "CBFβ-SMMHC Inhibition Disrupts Enhancer Chromatin Dynamics and Represses MYC Transcriptional Program in Inv (16) Leukemia.". Blood 130: 784. December 2017. doi:10.1182/blood.V130.Suppl_1.784.784.

- ↑ "Mechanisms of Oncogene-Induced Replication Stress: Jigsaw Falling into Place". Cancer Discovery 8 (5): 537–555. May 2018. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1461. PMID 29653955.

- ↑ "Pharmacological inhibition of aberrant transcription factor complexes in inversion 16 acute myeloid leukemia". Stem Cell Investigation 5: 30. 2018. doi:10.21037/sci.2018.09.03. PMID 30363728.

- ↑ "Reaching for high-hanging fruit in drug discovery at protein-protein interfaces". Nature 450 (7172): 1001–9. December 2007. doi:10.1038/nature06526. PMID 18075579. Bibcode: 2007Natur.450.1001W.

- ↑ "In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2". Science 303 (5659): 844–848. February 2004. doi:10.1126/science.1092472. PMID 14704432. Bibcode: 2004Sci...303..844V.

- ↑ "Drugging the p53 pathway: understanding the route to clinical efficacy". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 13 (3): 217–36. March 2014. doi:10.1038/nrd4236. PMID 24577402.

- ↑ "Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains". Nature 468 (7327): 1067–1073. December 2010. doi:10.1038/nature09504. PMID 20871596. Bibcode: 2010Natur.468.1067F.

- ↑ "A small-molecule inhibitor of BCL6 kills DLBCL cells in vitro and in vivo". Cancer Cell 17 (4): 400–411. April 2010. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.050. PMID 20385364.

- ↑ "Pharmacologic inhibition of the Menin-MLL interaction blocks progression of MLL leukemia in vivo". Cancer Cell 27 (4): 589–602. April 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.016. PMID 25817203.

- ↑ "An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours". Nature 435 (7042): 677–681. June 2005. doi:10.1038/nature03579. PMID 15902208. Bibcode: 2005Natur.435..677O.

|