Chemistry:Biocomposite

A biocomposite is a composite material formed by a matrix (resin) and a reinforcement of natural fibers. Environmental concern and cost of synthetic fibres have led the foundation of using natural fibre as reinforcement in polymeric composites. The matrix phase is formed by polymers derived from renewable and nonrenewable resources. The matrix is important to protect the fibers from environmental degradation and mechanical damage, to hold the fibers together and to transfer the loads on it. In addition, biofibers are the principal components of biocomposites, which are derived from biological origins, for example fibers from crops (cotton, flax or hemp), recycled wood, waste paper, crop processing byproducts or regenerated cellulose fiber (viscose/rayon). The interest in biocomposites is rapidly growing in terms of industrial applications (automobiles, railway coach, aerospace, military applications, construction, and packaging) and fundamental research, due to its great benefits (renewable, cheap, recyclable, and biodegradable). Biocomposites can be used alone, or as a complement to standard materials, such as carbon fiber. Advocates of biocomposites state that use of these materials improve health and safety in their production, are lighter in weight, have a visual appeal similar to that of wood, and are environmentally superior.[1][2][3][4]

Characteristics

The differential for this class of composites is that they are biodegradable and pollute the environment less which is a concern for many scientists and engineers to minimize the environmental impact of the production of a composite. They are a renewable source, cheap, and in certain cases completely recyclable.[5] One advantage of natural fibers is their low density, which results in a higher specific tensile strength and stiffness than glass fibers, besides of its lower manufacturing costs. As such, biocomposites could be a viable ecological alternative to carbon, glass, and man-made fiber composites. Natural fibers have a hollow structure, which gives insulation against noise and heat. It is a class of materials that can be easily processed, and thus, they are suited to a wide range of applications, such as packaging, building (roof structure, bridge, window, door, green kitchen), automobiles, aerospace, military applications, electronics, consumer products and medical industry (prosthetic, bone plate, orthodontic archwire, total hip replacement, and composite screws and pins). Unfortunately, biocomposites have limitations due to lack of compatibility between synthetic resin and natural fibers [6][7][8]

Classification

Biocomposites are divided into non-wood fibers and wood fibers, all of which present cellulose and lignin. The non-wood fibers (natural fibers) are more attractive for the industry due to the physical and mechanical properties which they present. Also, these fibers are relatively long fibers, and present high cellulose content, which delivers a high tensile strength, and degree of cellulose crystallinity, whereas natural fibers have some disadvantages because they have hydroxyl groups (OH) in the fiber that can attract water molecules, and thus, the fiber might swell. This results in voids at the interface of the composite, which will affect the mechanical properties and loss in dimensional stability. The wood fibers have this name because almost than 60% of its mass is wood elements. It presents softwood fibers (long and flexible) and hardwood fibers (shorter and stiffer), and has low degree of cellulose crystallinity.

| Biocomposites/biofibers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-wood natural fibers | Wood fibers | ||||||

| Straw fibers | Bast | Leaf | Seed/fruits | Grass fibers | Recycled | ||

| Examples: | Rice, wheat, corn straws | Kenaf, flax, jute, hemp | Henequen, sisal, penneaple leaf fiber | Cotton, coir, coconut | Bamboo, bamboo fiber, switch grass, elephant grass | Soft and hard woods | Newspaper, magazine fibers |

The natural fibers are divided into straw fibers, bast, leaf, seed or fruit, and grass fibers. The fibers most widely used in the industry are flax, jute, hemp, kenaf, sisal and coir. The straw fibers could be found in many parts of the world, and it is an example of a low-cost reinforcement for biocomposites. The wood fibers could be recycled or non-recycled. Thus, many polymers as polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) are being used in wood composites industries.

Flax applications

Flax linen composites work well for applications seeking a lighter weight alternative to other materials, most notably, applications in automotive interior components and sports equipment. For automotive interiors, Composites Evolution has performed prototype testing for the Land Rover Defender and the Jaguar XF, with the Defender's flax composite 60% lighter than the production counterpart at the same stiffness, and the XF's flax composite part 35% lighter than the production component at the same stiffness[9]

In sports equipment, Ergon Bikes produced a concept saddle that won first place among 439 entries in the Accessories category at the Eurobike 2012, a major bicycling industry trade show.[10] VE Paddles has produce a boat paddle blade.[11] Flaxland Canoes has developed a canoe that has a covering of flax linen.[12] Magine Snowboards has developed a snowboard that incorporates flax linen.[13] Samsara Surfboards has produced a flax linen surfboard.[14] Idris Ski's Lynx won an ISPO Award in 2013 for the Lynx ski[15]

Flax linen composites also work for applications for which the look, feel, or sound of wood is desired, but without susceptibility to warping. Applications include furniture and musical instruments. In furniture, a team at Sheffield Hallam University designed a cabinet with entirely sustainable materials, including flax linen.[16] In musical instruments, Blackbird Guitars has produced a ukulele made with flax linen that has won a number of design awards in the composites industry,[17][18][19][20] as well as a guitar[21]

Green composites

Green composites are classified as a biocomposite combined by natural fibers with biodegradable resins. They are called green composites mainly because of their degradable and sustainable properties, which can be easily disposed without harming the environment. Because of their durability, green composites are mainly used to increase the life cycle of products with short life.

Hybrid composites

Another class of biocomposite is called 'hybrid biocomposite', which is based on different types of fibers into a single matrix. The fibers can be synthetic or natural, and can be randomly combined to generate the hybrid composites. Its functionality depends directly on the balance between the good and bad properties of each individual material used. Besides, with the use of a composite that has two more types of fibers in the hybrid composite, one fiber can stand on the other one when it is blocked. The properties of this biocomposite depends directly on the fibers counting their content, length, arrangement, and also the bonding to the matrix. In particular, the strength of the hybrid composite depends on the failure strain of the individual fibers.

Hemp applications

Hemp fiber composites work well in applications where weight reduction and increased stiffness is important. For consumer good applications, Trifilon has developed a number of hemp fiber biocomposites to replace conventional plastics. Suitcases, chillboxes, mobile phone cases and cosmetic packaging have been produced using hemp fiber composites.

-

Hemp fiber composite suitcase

-

Hemp fiber composite - cosmetic packaging

-

Hemp fiber composite - mobile phone case

Processing

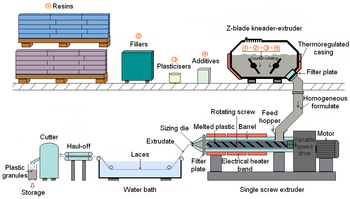

The production of biocomposites uses techniques that are used to manufacture plastics or composites materials. These techniques include:

- Machine press;

- Filament winding;

- Pultrusion;

- Extrusion (most widely used, principally for green biocomposite);

- Injection molding;

- Compression molding;

- Resin transfer molding;

- Sheet moulding compound.

References

- ↑ "Are natural fiber composites environmentally superior to glass fiber reinforced composites?". Michigan State University. https://www.msu.edu/user/satish/CompositsesA-final%20published.pdf.

- ↑ "They may be sustainable, but how good are flax and jute for the engineer?". Findlay Media. http://www.materialsforengineering.co.uk/engineering-materials-features/they-may-be-sustainable-but-how-good-are-flax-and-jute-for-the-engineer/52093/.

- ↑ "Bio-composites update: Beyond eco-branding". Gardner Business Media, Inc.. http://www.compositesworld.com/articles/biocomposites-update-beyond-eco-branding.

- ↑ "Biocomposites Guide". NetComposites Ltd. https://netcomposites.com/guide-tools/tools/biocomposites-guide/.

- ↑ "Are natural fiber composites environmentally superior to glass fiber reinforced composites?". Michigan State University. https://www.msu.edu/user/satish/CompositsesA-final%20published.pdf.

- ↑ Refiadi, Gunawan; Syamsiar, Yusi; Judawisastra, Hermawan (2019-09-05). "The Tensile Strength of Petung Bamboo Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Composites: The Effects of Alkali Treatment, Composites Manufacturing, and Water Absorption". IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 547: 012043. doi:10.1088/1757-899x/547/1/012043. ISSN 1757-899X.

- ↑ Judawisastra, H; Sitohang, R D R; Rosadi, M S (2017-09-20). "Water absorption and tensile strength degradation of Petung bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper) fiber—reinforced polymeric composites". Materials Research Express 4 (9): 094003. doi:10.1088/2053-1591/aa8a0d. ISSN 2053-1591. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/aa8a0d.

- ↑ Judawisastra, H; Sitohang, R D R; Marta, L; Mardiyati (July 2017). "Water absorption and its effect on the tensile properties of tapioca starch/polyvinyl alcohol bioplastics". IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 223: 012066. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/223/1/012066. ISSN 1757-8981.

- ↑ "Lightweight Stiff Door Module". Composites Evolution. http://www.compositesevolution.com/case-studies/lightweight-stiff-door-module/.

- ↑ "Ergon Bike Ergonomics flax saddle is acclaimed by the whole bike industry". Bcomp. http://www.playnaturallysmart.org/2012/08/30/ergon-bike-ergonomics-flax-saddle-is-acclaimed-by-the-whole-bike-industry/.

- ↑ "Flax composite paddle by VE Paddles using Bcomp's flax composite". The Center for Promotion of Composites. 2013-12-12. http://www.jeccomposites.com/news/composites-news/flax-composite-paddle-ve-paddles-using-bcomps-flax-composite.

- ↑ "Composites Evolution Showcase Biotex Flax Canoe". NetComposites. https://netcomposites.com/news/2011/september/20/composites-evolution-showcase-biotex-flax-canoe/.

- ↑ "Biocomposite snowboard using Biotex flax fabric". The Center for Promotion of Composite. June 2012. http://www.jeccomposites.com/news/composites-news/biocomposite-snowboard-using-biotex-flax-fabric.

- ↑ "Samsara 'eco surfboard' features Biotex flax fibre". Elsevier. http://www.materialstoday.com/carbon-fiber/news/samsara-eco-surfboard-features-biotex-flax-fibre/.

- ↑ "Idris Skis - Lynx - ISPO Award Winner 2013". ISPO. http://award.ispo.com/en/Winner-2013/Products/Ski/Ski-off-Piste/Idris-Skis/.

- ↑ "Lightweight Stiff Door Module". Sheffield Hallam University. http://www.shu.ac.uk/mediacentre/biodegradable-cabinet-new-approach-sustainability.

- ↑ "Blackbird launches plant fiber-based composite musical instrument". Gardner Business Media. http://www.compositesworld.com/news/blackbird-launches-plant-fiber-based-composite-musical-instrument.

- ↑ "Check Out the Competition: Visit the Awards Pavilion at The Composites And Advanced Material Expo (CAMX)". Gardner Business Media. http://www.compositesworld.com/articles/ace-and-camx-awards-nominees-announced.

- ↑ "Highlights from JEC Americas". Gardner Business Media. http://www.compositesworld.com/blog/post/highlights-from-jec-americas.

- ↑ "2014 IDSA IDEA Award - Bronze - Entertainment - Blackbird Clara Ukulele". Industrial Designers Society of America. 2014-06-20. http://www.idsa.org/awards/idea/entertainment/blackbird-clara-ukulele.

- ↑ "And Now, the Linen Guitar". Telegraph Media. http://www.oaklandmagazine.com/And-Now-the-Linen-Guitar/.

Bibliography

- Pingle, P. Analytical Modeling of Hard Biocomposites. ProQuest, 2008. University of Massachusetts Lowell. Website: https://books.google.com/books?id=XRLEstOKTiEC&q=biocomposites

- Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M.; Drzal, L.T. Natural Fibers, Biopolymers, and Biocomposites. CRC Press, 2005. Website: https://books.google.com/books?id=AwXugfY2oc4C&q=biocomposites

- Averous, L.; Le Digabel, F. Properties of biocomposites based on lignocellulosic fillers. Science Direct, 2006. Website: http://www.biodeg.net/fichiers/Properties%20of%20biocomposites%20based%20on%20lignocellulosic%20fillers%20(Proof).pdf

- Averous, L. Cellulose-based biocomposites: comparison of different multiphasic systems. Composite Interfaces, 2007. Website: http://www.biodeg.net/fichiers/Cellulosebased%20biocomposites%20(Abstract-Proof).pdf[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- Halonen, H. Structural changes during cellulose composite processing. Stockholm, 2012. Website: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:565072/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Fowler, P; Hughes, J; Elias, E. Biocomposites: technology, environmental credentials and market forces. Journal of the Science Food and Agriculture, 2006. Website: http://www.bc.bangor.ac.uk/_includes/docs/pdf/biocomposites%20technology.pdf

- Todkar, Santosh Sadashiv; Patil, Suresh Abasaheb (October 2019). "Review on mechanical properties evaluation of pineapple leaf fibre (PALF) reinforced polymer composites". Composites Part B: Engineering 174: 106927. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.106927.

|