Chemistry:Carborane

Carboranes (or carbaboranes) are electron-delocalized (non-classically bonded) clusters composed of boron, carbon and hydrogen atoms.[1] Like many of the related boron hydrides, these clusters are polyhedra or fragments of polyhedra. Carboranes are one class of heteroboranes.[2]

In terms of scope, carboranes can have as few as 5 and as many as 14 atoms in the cage framework. The majority have two cage carbon atoms. The corresponding C-alkyl and B-alkyl analogues are also known in a few cases.

Structure and bonding

Carboranes and boranes adopt 3-dimensional cage (cluster) geometries in sharp contrast to typical organic compounds. Cages are compatible with sigma—delocalized bonding, whereas hydrocarbons are typically chains or rings.

Like for other electron-delocalized polyhedral clusters, the electronic structure of these cluster compounds can be described by the Wade–Mingos rules. Like the related boron hydrides, these clusters are polyhedra or fragments of polyhedra, and are similarly classified as closo-, nido-, arachno-, hypho-, hypercloso-, iso-, klado-, conjuncto- and megalo-, based on whether they represent a complete (closo-) polyhedron or a polyhedron that is missing one (nido-), two (arachno-), three (hypho-), or more vertices. Carboranes are a notable example of heteroboranes.[2][3] The essence, these rules emphasize delocalized, multi-centered bonding for B-B, C-C, and B-C interactions.

Structurally, they can be considered to be related to the icosahedral (Ih) [B

12H

12]2− via formal replacement of two of its BH−

fragments with CH.

Isomers

Geometrical isomers of carboranes can exist on the basis of the various locations of carbon within the cage. Isomers necessitate the use of the numerical prefixes in a compound's name. The closo-dicarbadecaborane can exist in three isomers: 1,2-, 1,7-, and 1,12-C

2B

10H

12.

Preparation

Carboranes have been prepared by many routes, the most common being addition of alkynyl reagents to boron hydride clusters to form dicarbon carboranes. For this reason, the great majority of carborane have two carbon vertices.

Monocarba derivatives

Monocarboranes are clusters with B

nC cages. The 12-vertex derivative is best studied, but several are known.

Typically they are prepared by the addition of one-carbon reagents to boron hydride clusters. One-carbon reagents include cyanide, isocyanides, and formaldehyde. For example, monocarbadodecaborate ([CB

11H

12]−

) is produced from decaborane and formaldehyde, followed by addition of borane dimethylsulfide.[4][5]

Monocarboranes are precursors to weakly coordinating anions.[6]

Dicarba clusters

Dicarbaboranes can be prepared from boron hydrides using alkynes as the source of the two carbon centers. In addition to the closo-C

2B

nH

n+2 series mentioned above, several open-cage dicarbon species are known including nido-C

2B

3H

7 (isostructural and isoelectronic with B

5H

9) and arachno-C

2B

7H

13.

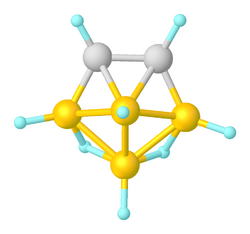

2B

4H

8, highlighting some trends: carbon at the low connectivity sites, bridging hydrogen between B centers on open face[7]

Syntheses of icosahedral closo-dicarbadodecaborane derivatives (R

2C

2B

10H

10) employ alkynes as the R

2C

2 source and decaborane (B

10H

14) to supply the B

10 unit.

Classification by cage size

The following classification is adapted from Grimes's book on carboranes.[1]

Small, open carboranes

This family of clusters includes the nido cages CB

5H

9, C

2B

4H

8, C

3B

3H

7, C

4B

2H

6, and C

2B

3H

7. Relatively little work has been devoted to these compounds. Pentaborane[9] reacts with acetylene to give nido-1,2-C

2B

4H

8. Upon treatment with sodium hydride, latter forms the salt [1,2-C

2B

4H

7]−

Na+

.

Small, closed carboranes

This family of clusters includes the closo cages C

2B

3H

5, C

2B

4H

6, C

2B

5H

7, and CB

5H

7. This family of clusters are also lightly studied owing to synthetic difficulties. Also reflecting synthetic challenges, many of these compounds are best known as their alkyl derivatives. 1,5-C

2B

3H

5 is the only known isomer of the five-vertex cage. It is prepared from the reaction of pentaborane(9) with acetylene in two operations beginning with condensation with acetylene followed by pyrolysis (cracking) of the product:

- B

5H

9 + C

2H

2 → nido-2,3-C

2B

4H

8 + BH

3 - C

2B

4H

8 → closo-2,3-C

2B

3H

5 + BH

3

Intermediate-sized carboranes

2B

7H

13 (all unlabeled vertices are BH).

Structures

This family of clusters includes the closo cages C

2B

6H

8, C

2B

7H

9, C

2B

8H

10 and C

2B

9H

11 and their derivatives.

Isomerism is well established in this family:

- 2,3- and 2,4-C

2B

4H

8 - 2,3- and 2,4-C

2B

5H

7 - 1,2- and 1,6-C

2B

6H

8 - 1,10-, 1,6-, and 1,2-C

2B

8H

10[8] - 1,2 and 1,3-C

2B

9H

13.

Syntheses

Carboranes of intermediate nuclearity are most efficiently generated by degradations from larger clusters. In contrast, smaller carboranes are usually prepared by building-up routes, e.g. from pentaborane + alkyne, etc.

For example ortho-carborane can be degraded to give [C

2B

9H

12]−

,[9] which can be manipulated with oxidants, protonation, and thermolysis.

- [C

2B

9H

12]−

+ Fe3+ → C

2B

8H

12 + "B+

" + Fe2+ - [C

2B

9H

12]−

+ H+

→ C

2B

9H

13 - C

2B

9H

13 → C

2B

9H

11 + H

2

Chromate oxidation of 11-vertex clusters results in deboronation, giving C

2B

7H

13. From that species, other clusters result by pyrolysis, sometimes in the presence of diborane: C

2B

6H

8, C

2B

8H

10, and C

2B

7H

9.[1]

In general, isomers having non-adjacent cage carbon atoms are more thermally stable than those with adjacent carbons. Thus, heating tends to induce mutual separation of the carbon atoms in the framework.

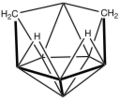

Icosahedral carboranes

The icosahedral charge-neutral closo-carboranes, 1,2-, 1,7-, and 1,12- C

2B

10H

12 (informally ortho-, meta-, and para-carborane) are particularly stable and are commercially available.[10][11] The ortho-carborane forms first upon the reaction of decaborane and acetylene. It converts quantitatively to the meta-carborane upon heating in an inert atmosphere. Producing meta-carborane from ortho-carborane requires 700 °C, proceeding in ca. 25% yield.[1]

[CB

11H

12]−

is also well established.

Reactions

The metalation of carboranes is illustrated by the reactions of closo-C

2B

3H

5 with iron carbonyl sources. Two closo Fe- and Fe

2-containing products are obtained, according to these idealized equations:

- C

2B

3H

5 + Fe

2(CO)

9 → C

2B

3H

5Fe(CO)

3 + Fe(CO)

5 + CO - C

2B

3H

5Fe(CO)

3 + Fe

2(CO)

9 → C

2B

3H

5(Fe(CO)

3)

2 + Fe(CO)

5 + CO

Base-induced degradation of carboranes give anionic nido derivatives, which can also be employed as ligands for transition metals, generating metallacarboranes, which are carboranes containing one or more transition metal or main group metal atoms in the cage framework. Most famous are the dicarbollide, complexes with the formula M2+[C

2B

9H

11]2−, where M stands for metal.[12]

Research

Dicarbollide complexes have been investigated for many years, but commercial applications are rare. The bis(dicarbollide) [Co(C

2B

9H

11)

2]−

has been used as a precipitant for removal of [[Physics:Caesium−

137|137

Cs]]+

from radiowastes.[13]

The medical applications of carboranes have been explored.[14][15] C-functionalized carboranes represent a source of boron for boron neutron capture therapy.[16]

The compound H(CHB

11Cl

11) is a superacid, forming an isolable salt with protonated benzene cation, [C

6H

7]+

(benzenium cation).[17] The formula of that salt is [C

6H

7]+

[CHB

11Cl

11]−

. The superacid protonates fullerene, C

60.[18]

See also

- Azaborane

- Heteroborane

- Metallacarboranes

- Organoboron chemistry

- Dicarbollide

- Carborane acid

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Grimes, R. N. (2016). Carboranes (3 ed.). Amsterdam and New York: Elsevier. ISBN 9780128018941.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 181–189. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ↑ The Wade–Mingos rules were first stated by Kenneth Wade in 1971 and expanded by Michael Mingos in 1972:

- Wade, Kenneth (1971). "The structural significance of the number of skeletal bonding electron-pairs in carboranes, the higher boranes and borane anions, and various transition-metal carbonyl cluster compounds". J. Chem. Soc. D 1971 (15): 792–793. doi:10.1039/C29710000792.

- Mingos, D. M. P. (1972). "A general theory for cluster and ring compounds of the main group and transition elements". Nature Physical Science 236 (68): 99–102. doi:10.1038/physci236099a0. Bibcode: 1972NPhS..236...99M.

- Welch, Alan J. (2013). "The significance and impact of Wade's rules". Chem. Commun. 49 (35): 3615–3616. doi:10.1039/C3CC00069A. PMID 23535980.

- ↑ W. H. Knoth (1967). "1-B9H9CH− and B11H11CH−". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 89 (5): 1274–1275. doi:10.1021/ja00981a048.

- ↑ Tanaka, N.; Shoji, Y.; Fukushima, T. (2016). "Convenient Route to Monocarba-closo-dodecaborate Anions". Organometallics 35 (11): 2022–2025. doi:10.1021/acs.organomet.6b00309.

- ↑ Reed, Christopher A. (2010). "H+, CH3+, and R3Si+Carborane Reagents: When Triflates Fail". Accounts of Chemical Research 43 (1): 121–128. doi:10.1021/ar900159e. PMID 19736934.

- ↑ G. S. Pawley (1966). "Further Refinements of Some Rigid Boron Compounds". Acta Crystallogr. 20 (5): 631–638. doi:10.1107/S0365110X66001531. Bibcode: 1966AcCry..20..631P.

- ↑ Štíbr, Bohumil (2018). "Recent aspects of the ten-vertex dicarbaborane chemistry". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 865: 4–11. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.01.010.

- ↑ Plešek, J.; Heřmánek, S.; Štíbr, B. (1983). "Potassium dodecahydro-7, 8-dicarba- nido -undecaborate(1-), k[7, 8-c 2 b 9 h 12 ], intermediates, stock solution, and anhydrous salt". Potassium Dodecahydro-7,8-Dicarba-nido-Undecaborate (1-), K[ 7,8-C2B9H13], Intermediates, Stock Solution, and Anhydrous Salt. Inorganic Syntheses. 22. p. 231-237. doi:10.1002/9780470132531.ch53. ISBN 978-0-471-88887-1. https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/jbuss/wp-content/uploads/sites/811/2020/08/inorganic-synthesis22.pdf#page=244.

- ↑ Jemmis, E. D. (1982). "Overlap Control and Stability of Polyhedral Molecules. Closo-Carboranes". Journal of the American Chemical Society 104 (25): 7017–7020. doi:10.1021/ja00389a021.

- ↑ Spokoyny, A. M. (2013). "New Ligand Platforms Featuring Boron-Rich Clusters as Organomimetic Sbstituents". Pure and Applied Chemistry 85 (5): 903–919. doi:10.1351/PAC-CON-13-01-13. PMID 24311823.

- ↑ Sivaev, I. B.; Bregadze, V. I. (2000). "Chemistry of Nickel and Iron Bis(dicarbollides). A Review". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 614-615: 27–36. doi:10.1016/S0022-328X(00)00610-0.

- ↑ Dash, B. P.; Satapathy, R.; Swain, B. R.; Mahanta, C. S.; Jena, B. B.; Hosmane, N. S. (2017). "Cobalt Bis(dicarbollide) anion and its Derivatives". J. Organomet. Chem. 849–850: 170–194. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2017.04.006.

- ↑ Issa, F.; Kassiou, M.; Rendina, L. M. (2011). "Boron in drug discovery: carboranes as unique pharmacophores in biologically active compounds". Chem. Rev. 111 (9): 5701–5722. doi:10.1021/cr2000866. PMID 21718011.

- ↑ Stockmann, Philipp; Gozzi, Marta; Kuhnert, Robert; Sárosi, Menyhárt B.; Hey-Hawkins, Evamarie (2019). "New keys for old locks: carborane-containing drugs as platforms for mechanism-based therapies". Chemical Society Reviews 48 (13): 3497–3512. doi:10.1039/C9CS00197B. PMID 31214680.

- ↑ Soloway, A. H.; Tjarks, W.; Barnum, B. A.; Rong, F.-G.; Barth, R. F.; Codogni, I. M.; Wilson, J. G. (1998). "The Chemistry of Neutron Capture Therapy". Chemical Reviews 98 (4): 1515–1562. doi:10.1021/cr941195u. PMID 11848941.

- ↑ Olah, G. A.; Prakash, G. K. S.; Sommer, J.; Molnar, A. (2009). Superacid Chemistry (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-471-59668-4. https://archive.org/details/superacidchemist00olah.

- ↑ Reed Christopher A (2013). "Myths about the Proton. The Nature of H+ in Condensed Media". Acc. Chem. Res. 46 (11): 2567–2575. doi:10.1021/ar400064q. PMID 23875729.

External links

|