Chemistry:Cluster chemistry

In chemistry, a cluster is an ensemble of bound atoms or molecules that is intermediate in size between a molecule and a bulk solid. Clusters exist of diverse stoichiometries and nuclearities. For example, carbon and boron atoms form fullerene and borane clusters, respectively. Transition metals and main group elements form especially robust clusters.[1] Clusters can also consist solely of a certain kind of molecules, such as water clusters. The phrase cluster was coined by F.A. Cotton in the early 1960s to refer to compounds containing metal–metal bonds. In another definition a cluster compound contains a group of two or more metal atoms where direct and substantial metal bonding is present.[2] The prefixed terms "nuclear" and "metallic" are used and imply different meanings. For example, polynuclear refers to a cluster with more than one metal atom, regardless of the elemental identities. Heteronuclear refers to a cluster with at least two different metal elements.

The main cluster types are "naked" clusters (without stabilizing ligands) and those with ligands. For transition metal clusters, typical stabilizing ligands include carbon monoxide, halides, isocyanides, alkenes, and hydrides. For main group elements, typical clusters are stabilized by hydride ligands.

Transition metal clusters are frequently composed of refractory metal atoms. In general metal centers with extended d-orbitals form stable clusters because of favorable overlap of valence orbitals. Thus, metals with a low oxidation state for the later metals and mid-oxidation states for the early metals tend to form stable clusters. Polynuclear metal carbonyls are generally found in late transition metals with low formal oxidation states. The polyhedral skeletal electron pair theory or Wade's electron counting rules predict trends in the stability and structures of many metal clusters. Jemmis mno rules have provided additional insight into the relative stability of metal clusters.

History and classification

The development of cluster chemistry occurred contemporaneously along several independent lines, which are roughly classified in the following sections. The first synthetic metal cluster was probably calomel, which was known in India already in the 12th century. The existence of a mercury to mercury bond in this compound was established in the beginning of the 20th century.

Atomic clusters

Atomic clusters can be either pure, formed from a single atomic species, or mixed, formed from a mixed atomic species. Classifications criteria:

- by predominant bond nature: metallic, covalent, ionic;

- by atomic count: "micro" < 20, "small" < 100 < "large"

- by electric / magnetic properties

For the majority of atomic species there are clusters of certain atomic counts (so-called "magic numbers") that have preponderent representation in the mass spectra, an indication of their greater stability with respect to dissociation when compared to their neighboring atomic counts.

Molecular clusters

Atomic and molecular clusters are aggregates of 5-105 atomic or molecular units. They are classified according to the forces holding them together:

- Van der Waals clusters - attraction between induced electric dipoles and repulsion between electron cores of closed electronic configurations

- Metallic clusters - long range valence electron sharing (over many successive adjacent atoms) and partially directional

- Ionic clusters - valence electrons are almost entirely transferred among closest neighbors to yield 2 net, equal but opposite, electric charge distributions that mutually attract.

Quantum many-body mechanisms are also important.

The role of cluster formation in the precipitation of liquid mixtures and in the condensation, adsorption to surface or solidification phase transitions has long been investigated from a theoretical standpoint.

Cluster system properties — stem both from their size and composition (which contributes to the binding force types) that determine:

- the number of dimensions of their phase space

- the ranges of accessible positions and velocities of their atomic components

A gradual transition occurs between the properties of the molecular species and those of the corresponding bulk mix. And yet the clusters exhibit physical and chemical properties specific only to their configuration space (in turn strongly atom-count-dependent) and not specific to their bulk counterparts.

Cluster systems are metastable with respect to at least one of the following evolution classes:

- atom elimination or adsorption at cluster surface as a cause for their disassociation or growth

- configuration switches among a set of stable structures (a.k.a. an "isomer class") accessible to all clusters of a same atom count and a same relative component composition.

Many of their properties are due to the fact that a large fraction of their component atoms is found at their surface. With increasing size, the relative number of atoms at the cluster surface will scale approximately as N−1/3. One has to reach beyond a variable threshold of 9-27 component molecules (depending on the strength of the inter-molecular forces) to find global minimum configurations that hold at least one interior molecule. At the other end of the scale a cluster of about 105 atoms will expose only about 10% of the atoms at its surface, a still significant percentage in comparison to the bulk solid.

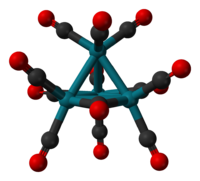

Transition metal carbonyl clusters

The development of metal carbonyl clusters such as Ni(CO)4 and Fe(CO)5 led quickly to the isolation of Fe2(CO)9 and Fe3(CO)12. Rundle and Dahl discovered that Mn2(CO)10 featured an "unsupported" Mn-Mn bond, thereby verifying the ability of metals to bond to one another in molecules. In the 1970s, Paolo Chini demonstrated that very large clusters could be prepared from the platinum metals, one example being [Rh13(CO)24H3]2−. This area of cluster chemistry has benefited from single-crystal X-ray diffraction.

Transition metal organic carbon (organometallic) clusters

Organometallic clusters contain metal-metal bonds as well as at least one C-M bonds. One example is the methylidyne-tricobalt cluster [Co3(CH)(CO)9].[3] The above-mentioned cluster serves as an example of an overall zero-charged (neutral) cluster. In addition, cationic (positively charged) rather than neutral organometallic trimolybdenum[4][5] or tritungsten[6] clusters are also known. The first representative of these ionic organometallic clusters is [Mo3(CCH3)2(O2CCH3)6(H2O)3]2+.

Transition metal halide clusters

Linus Pauling showed that "MoCl2" consisted of Mo6 octahedra. F. Albert Cotton established that "ReCl3" in fact features subunits of the cluster Re3Cl9, which could be converted to a host of adducts without breaking the Re-Re bonds. Because this compound is diamagnetic and not paramagnetic the rhenium bonds are double bonds and not single bonds. In the solid state further bridging occurs between neighbours and when this compound is dissolved in hydrochloric acid a Re3Cl123− complex forms. An example of a tetranuclear complex is hexadecamethoxytetratungsten W4(OCH3)12 with tungsten single bonds and molybdenum chloride ((Mo6Cl8)Cl4) is a hexanuclear molybdenum compound and an example of an octahedral cluster. A related group of clusters with the general formula MxMo6X8 such as PbMo6S8 form a Chevrel phase, which exhibit superconductivity at low temperatures. The eclipsed structure of potassium octachlorodirhenate(III), K2Re2Cl8 was explained by invoking Quadruple bonding. This discovery led to a broad range of derivatives including di-tungsten tetra(hpp), the current (2007) record holder low ionization energy.

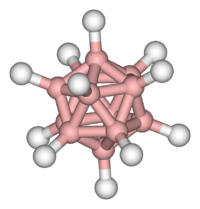

Boron hydrides

Contemporaneously with the development of metal cluster compounds, numerous boron hydrides were discovered by Alfred Stock and his successors who popularized the use of vacuum-lines for the manipulation of these often volatile, air-sensitive materials. Clusters of boron are boranes such as pentaborane and decaborane. Composite clusters containing CH and BH vertices are carboranes.

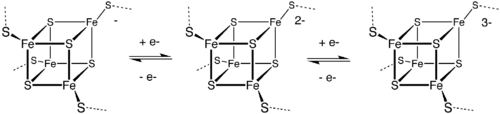

Fe-S clusters in biology

In the 1970s, ferredoxin was demonstrated to contain Fe4S4 clusters and later nitrogenase was shown to contain a distinctive MoFe7S9 active site.[7] The Fe-S clusters mainly serve as redox cofactors, but some have a catalytic function. In the area of bioinorganic chemistry, a variety of Fe-S clusters have also been identified that have CO as ligands.

Zintl clusters

Zintl compounds feature naked anionic clusters that are generated by reduction of heavy main group p elements, mostly metals or semimetals, with alkali metals, often as a solution in anhydrous liquid ammonia or ethylenediamine.[8] Examples of Zintl anions are [Bi3]3−, [Sn9]4−, [Pb9]4−, and [Sb7]3−.[9] Although these species are called "naked clusters," they are usually strongly associated with alkali metal cations. Some examples have been isolated using cryptate complexes of the alkali metal cation, e.g., [Pb10]2− anion, which features a capped square antiprismatic shape.[10] According to Wade's rules (2n+2) the number of cluster electrons is 22 and therefore a closo cluster. The compound is prepared from oxidation of K4Pb9 [11] by Au+ in PPh3AuCl (by reaction of tetrachloroauric acid and triphenylphosphine) in ethylene diamine with 2.2.2-crypt. This type of cluster was already known as is the endohedral Ni@Pb102− (the cage contains one nickel atom). The icosahedral tin cluster Sn122− or stannaspherene anion is another closed shell structure observed (but not isolated) with photoelectron spectroscopy.[12][13] With an internal diameter of 6.1 Ångstrom, it is of comparable size to fullerene and should be capable of containing small atoms in the same manner as endohedral fullerenes, and indeed exists a Sn12 cluster that contains an Ir atom: [Ir@Sn12]3−.[14]

Metalloid clusters

Elementoid clusters are ligand-stabilized clusters of metal atoms that possess more direct element-element than element-ligand contacts. Examples of structurally characterized clusters feature ligand stabilized cores of Al77, Ga84, and Pd145.[15]

Intermetalloid clusters

These clusters consist of at least two different (semi)metallic elements, and possess more direct metal-metal than metal-ligand contacts. The suffix "oid" designate that such clusters possess at a molecular scale, atom arrangements that appear in bulk intermetallic compounds with high coordination numbers of the atoms, such as for example in Laves phase and Hume-Rothery phases.[16] Ligand-free intermetalloid clusters include also endohedrally filled Zintl clusters.[9][17] A synonym for ligand-stabilized intermetalloid clusters is "molecular alloy". The clusters appear as discrete units in intermetallic compounds separated from each other by electropositive atoms such as [Sn@Cu12@Sn20]12−,[16] as soluble ions [As@Ni12@As20]3−[9] or as ligand-stabilized molecules such as [Mo(ZnCH3)9(ZnCp*)3].[18]

Gas-phase clusters and fullerenes

Unstable clusters can also be observed in the gas-phase by means of mass spectrometry, even though they may be thermodynamically unstable and aggregate easily upon condensation. Such naked clusters, i.e. those that are not stabilized by ligands, are often produced by laser induced evaporation - or ablation - of a bulk metal or metal-containing compound. Typically, this approach produces a broad distribution of size distributions. Their electronic structures can be interrogated by techniques such as photoelectron spectroscopy, while infrared multiphoton dissociation spectroscopy is more probing the clusters geometry.[19] Their properties (Reactivity, Ionization potential, HOMO–LUMO-gap) often show a pronounced size dependence. Examples of such clusters are certain aluminium clusters as superatoms and certain gold clusters. Certain metal clusters are considered to exhibit metal aromaticity. In some cases, the results of laser ablation experiments are translated to isolated compounds, and the premier cases are the clusters of carbon called the fullerenes, notably clusters with the formula C60, C70, and C84. The fullerene sphere can be filled with small molecules, forming Endohedral fullerenes.

Extended metal atom chains

Extended metal atom chain complexes (EMAC) are a novel topic in academic research. An EMAC is composed of linear chains of metal atoms stabilized with ligands. EMACs are known based on nickel (with 9 atoms), chromium and cobalt (7 atoms) and ruthenium (5 atoms). In theory it should be possible to obtain infinite one-dimensional molecules and research is oriented towards this goal. In one study [20] an EMAC was obtained that consisted of 9 chromium atoms in a linear array with 4 ligands (based on an oligo pyridine) wrapped around it. In it the chromium chain contains 4 quadruple bonds.

Metal clusters in catalysis

Although few metal carbonyl clusters are catalytically useful, naturally occurring Iron-sulfur proteins catalyse a variety of transformations, such as the stereo-specific isomerization of citrate to isocitrate via cis-aconitate, as required by the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Nitrogen is reduced to ammonia at an Fe-Mo-S cluster at the heart of the enzyme nitrogenase. CO is oxidized to CO2 by the Fe-Ni-S cluster carbon monoxide dehydrogenase. Hydrogenases rely on Fe2 and NiFe clusters.[21] Isoprenoid biosynthesis, at least in certain organisms, requires Fe-S clusters.[22] Some extremely active ligand-free clusters are formed during chemical reactions, without ligands,[23] and, only recently, they can be isolated and perfectly characterized.[24]

Catalysis by metal carbonyl clusters

Metal carbonyl cluster compounds have been evaluated as catalysts for a wide range of reactions, especially for conversions of carbon monoxide.[25] No industrial applications exist however. The clusters Ru3(CO)12 and Ir4(CO)12 catalyze the Water gas shift reaction, also catalyzed by iron oxide, and Rh6(CO)16 catalyzes the conversion of carbon monoxide into hydrocarbons, reminiscent of the Fischer-Tropsch process, also catalyzed by simple iron compounds.

Some define cluster catalysis to include clusters that have only one active site on one metal atom. The definition can be further relaxed to include clusters that remain intact during at least one reaction step, and can be fragmented in all others.[26]

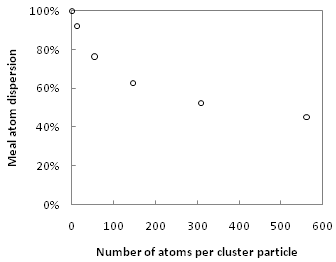

Metal carbonyl clusters have several properties that suggest that they may prove as useful catalysts. The absence of large bulk phases leads to a high surface-to-volume ratio, which is advantageous in any catalyst application as this maximizes the reaction rate per unit amount of catalyst material, which also minimizes cost.[27] Although surface metal sites in heterogeneous catalysts are coordinatively unsaturated, most synthetic clusters are not. In general, as the number of atoms in a metal particle decrease, their coordination number decreases, and significantly so in particles having less than 100 atoms.[28] This is illustrated by the figure at right, which shows dispersion (ratio of undercoordinated surface atoms to total atoms) versus number of metal atoms per particle for ideal icosahedral metal clusters.

Stereodynamics of clusters

Metal clusters are sometimes characterized by a high degree of fluxionality of surface ligands and adsorbates associated with a low energy barrier to rearrangement of these species on the surface.[29][30] The rearrangement of ligands on a cluster exterior is indirectly related to the diffusion of adsorbates on solid metal surfaces. Interconversion ligands between terminal, double-, and triply bridging sites is often facile. It has further been found that metal atoms themselves can easily migrate in or break their bonds with the cluster structure.[31][28]

Appendix: examples of reactions catalysed by transition metal carbonyl clusters

Although not used for any commercial process, metal carbonyl clusters have been subjected to many studies aimed at demonstrating their reactivity. Some of these examples include the following:

| Reaction | Core Metals | Catalyst | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alkene hydroformylation | Mo-Rh | Mo2RhCp3(CO)5 | [32] |

| Alkene hydroformylation | Rh | Rh4(CO)10+x(PPh3)2−x (x=0,2) | [33] |

| CO hydrogenation | Ru-Os | H2RuOs3(CO)13 | [32] |

| CO hydrogenation | Ru-Co | RuCo2(CO)11 | [32] |

| CO hydrogenation | Ir | Ir4(CO)12 | [31][33][34] |

| CO hydrogenation | Fe | Fe3(CO)12 | [35] |

| Alkene hydrogenation | Os-Ni | H3Os3NiCp(CO)9 | [32] |

| Alkene hydrogenation | Ni | Ni2+xCp2+x(CO)2 (x=0,1) | [33] |

| Alkyne hydrogenation | Os-Ni | Os3Ni3Cp3(CO)9 | [32] |

| Hydrogenation of aromatics | Ni | Ni2+xCp2+x(CO)2 (x=0,1) | [33] |

| Acetaldehyde hydrogenation | Ni | Ni4(Me3CNC)7 | [33] |

| Alkene isomerization | V-Cr | VCrCp3(CO)3 | [32] |

| Hydrocarbon isomerization | Fe-Pt | Fe2Pt(CO)6(NO)2(Me3CNC)2 | [32] |

| Butane hydrogenolysis | Rh-Ir | Rh3+xIr3−x(CO)16 (x=0,1,2) | [32] |

| Methanol hydrocarbonylation | Ru-Co | Ru2Co2(CO)13 | [32] |

| Hydrodesulfurization | Mo-Fe | Mo2Fe2S2Cp2(CO)8 | [32] |

| CO and CO2 methanation | Ru-Co | HRuCo3(CO)12 | [32] |

| Ammonia synthesis | Ru-Ni | H3Ru3NiCp(CO)9 | [32] |

Fischer-Tropsch catalysis

Species that are typical ligands for a metal cluster represent obvious reactant-catalyst combinations.[26][29] For example, hydrogenation of CO (Fischer-Tropsch synthesis) can be catalyzed using several metal clusters, as shown in the table above. It has been proposed that coordination of CO to multiple metal sites weakens the triple-bond enough to allow hydrogenation.[31] As in the industrially significant heterogeneous process, Fischer-Tropsch synthesis by clusters yields alkanes, alkenes, and various oxygenates. The selectivity is heavily influenced by the particular cluster used. For example, Ir4(CO)12 produces methanol, whereas Ru2Rh(CO)12 produces ethylene glycol.[31] Selectivity is determined by several factors, including steric and electronic effects. Steric effects are the most important consideration in many cases, however electronic effects dominate in hydrogenation reactions where one adsorbate (hydrogen) is relatively small.[26]

In some cases, a metal cluster must be "activated" for catalysis by substitution of one or more ligands, such as acetonitrile.[36] For example, Os3(CO)12 will have one active site after thermolysis and the dissociation of a single carbonyl group. Os3(CO)10(CH3CN)2 will have two active sites.[26]

Computational studies

Computational studies have progressed from sum-of-energies calculations (incorporating Hückel theory-type approximations) to density functional theory (DFT). An example of the former is empirical packing energy calculations, where only interactions between adjacent atoms are considered. The packing potential energy can be expressed as follows:

[math]\displaystyle{ E = \sum_i \sum_j \left (A \mathrm{e}^{-Br_{ij}}-Cr_{ij}-\frac{q_iq_j}{r_{ij}} \right ) }[/math]

where index i refers to all atoms of a reference molecule in the cluster lattice, index j refers to atoms in surrounding molecules according to crystal symmetry, and A, B, and C are parameters.[30] The advantage of such methods is ease of computation, however accuracy is dependent on the particular assumptions made. DFT has been used more recently to study a wide variety of properties of metal clusters.[37][38][39] Its advantages are being a first-principles approach without need of parameters, and the ability to study clusters without ligands of a definitive size. However the fundamental form of the energy functional is only approximately known, and unlike other methods there is no hierarchy of approximations which allow a systematic optimization of results.[39]

Tight bonding molecular dynamics has been used to study bond lengths, bond energies, and magnetic properties of metal clusters, however this method is less effective for clusters with less than 10-20 metal atoms due to a larger influence of approximation errors for small clusters.[40] There are limitations on the other extreme as well that exist with any computation method, that the approach to bulk-like properties is difficult to capture because at these cluster sizes the cluster model becomes increasingly complex.

See also

- Cluster

- Water molecules form clusters as well: see water clusters

- Metallaprism

- Paolo Chini

- Metal carbonyl cluster

References

- ↑ Inorganic Chemistry Huheey, JE, 3rd ed. Harper and Row, New York

- ↑ Mingos, D. M. P.; Wales, D. J. (1990). Introduction to cluster chemistry. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0134743059.

- ↑ D. Seyferth (1976). "Chemistry of Carbon-Functional Alkylidynetricobalt Nonacarbonyl Cluster Complexes". Adv. Organomet. Chem. 14: 97–144. doi:10.1016/s0065-3055(08)60650-4.

- ↑ A. Bino; M. Ardon; I. Maor; M. Kaftory; Z. Dori (1976). "[Mo3(OAc)6(CH3CH2O)2(H2O)3]2+ and Other New Products of the Reaction between Molybdenum Hexacarbonyl and Acetic Acid". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 98: 7093–7095. doi:10.1021/ja00438a067.

- ↑ A. Bino; F. A. Cotton; Z. Dori (1981). "A New Aqueous Chemistry of Organometallic, Trinuclear Cluster Compounds of Molybdenum". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103: 243–244. doi:10.1021/ja00391a068.

- ↑ F. A. Cotton; Z. Dori; M. Kapon; D. O. Marler; G. M. Reisner; W. Schwotzer; M. Shaia (1985). "The First Alkylidyne-Capped Tritungsten(IV) Cluster Compounds: Preparation, Structure, and Properties of [W3O(CCH3)(O2CCH3)6(H2O)3]Br2*2H2O". Inorg. Chem. 24: 4381–4384. doi:10.1021/ic00219a036.

- ↑ "Metal Clusters in Chemistry" P. Braunstein, L. A. Oro, P. R. Raithby, eds Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 1999. ISBN:3-527-29549-6.

- ↑ S. Scharfe; F. Kraus; S. Stegmaier; A. Schier; T. F. Fässler (2011). "Homoatomic Zintl Ions, Cage Compounds, and Intermetalloid Clusters of Group 14 and Group 15 Elements". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 50: 3630–3670. doi:10.1002/anie.201001630.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Zintl Ions: Principles and Recent Developments, Book Series: Structure and Bonding. T. F. Fässler (Ed.), Volume 140, Springer, Heidelberg, 2011 doi:10.1007/978-3-642-21181-2

- ↑ A. Spiekermann; S. D. Hoffmann; T. F. Fässler (2006). "The Zintl Ion [Pb10]2−: A Rare Example of a Homoatomic closo Cluster". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 45 (21): 3459–3462. doi:10.1002/anie.200503916. PMID 16622888.

- ↑ itself made by heating elemental potassium and lead at 350°C

- ↑ Tin particles are generated as K+Sn122− by laser evaporation from solid tin containing 15% potassium and isolated by mass spectrometer before analysis

- ↑ Li-Feng Cui; Xin Huang; Lei-Ming Wang; Dmitry Yu. Zubarev; Alexander I. Boldyrev; Jun Li; Lai-Sheng Wang (2006). "Sn122−: Stannaspherene". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (26): 8390–8391. doi:10.1021/ja062052f. PMID 16802791.

- ↑ J.-Q. Wang; S. Stegmaier; B. Wahl; T. F. Fässler (2010). "Step by Step Synthesis of the Endohedral Stannaspherene [Ir@Sn12]3− via the Capped Cluster Anion [Sn9Ir(COD)]3−". Chem. Eur. J. 16: 3532–3552. doi:10.1002/chem.200902815.

- ↑ A. Schnepf; H. Schnöckel (2002). "Metalloid aluminum and gallium clusters: element modifications on the molecular scale?". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 114: 1793–1798. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20021004)41:19<3532::AID-ANIE3532>3.0.CO;2-4.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 S. Stegmaier; T. F. Fässler (2011). "A Bronze Matryoshka – The Discrete Intermetalloid Cluster [Sn@Cu12@Sn20]12− in the Ternary Phases A12Cu12Sn21 (A = Na, K)". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133: 19758–19768. doi:10.1021/ja205934p.

- ↑ T. F. Fässler; S. D. Hoffmann (2004). "Endohedral Zintl Ions: Intermetalloid Clusters". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 116: 6400–6406. doi:10.1002/anie.200460427.

- ↑ R. A. Fischer (2008). "Twelve One-Electron Ligands Coordinating One Metal Center: Structure and Bonding of [Mo(ZnCH3)9(ZnCp*)3]". Angewandte Chemie International Edition 47: 9150–9154. doi:10.1002/anie.200802811.

- ↑ "Structure determination of isolated metal clusters via far-infrared spectroscopy". Phys. Rev. Lett. 93 (2): 023401. 2004. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.023401. PMID 15323913. Bibcode: 2004PhRvL..93b3401F. http://pubman.mpdl.mpg.de/pubman/item/escidoc:739325/component/escidoc:1477675/e023401.pdf.

- ↑ Rayyat H. Ismayilov; Wen-Zhen Wang; Rui-Ren Wang; Chen-Yu Yeh; Gene-Hsiang Lee; Shie-Ming Peng (2007). "Four quadruple metal–metal bonds lined up: linear nonachromium(II) metal string complexes". Chem. Commun. (11): 1121–1123. doi:10.1039/b614597c. PMID 17347712.

- ↑ Bioorganometallics: Biomolecules, Labeling, Medicine; Jaouen, G., Ed. Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2006.3-527-30990-X.

- ↑ Eric Oldfield "Targeting Isoprenoid Biosynthesis for Drug Discovery: Bench to Bedside" Acc. Chem. Res., 2010, 43 (9), pp 1216–1226. doi:10.1021/ar100026v

- ↑ Oliver-Meseguer, Judit; Cabrero-Antonino, Jose R.; Domínguez, Irene; Leyva-Pérez, Antonio; Corma, Avelino (2012). "Small Gold Clusters Formed in Solution Give Reaction Turnover Numbers of 10 Millions at Room Temperature". Science: AAAS. pp. 1452–1455 (338).

- ↑ "The MOF-driven synthesis of supported palladium clusters with catalytic activity for carbene-mediated chemistry". Nature Materials: Springer Nature. 2017. pp. 760-766 (16).

- ↑ Cluster Chemistry: Introduction to the Chemistry of Transition Metal and Main Group Element Molecular Clusters Guillermo Gonzalez-Moraga 1993 ISBN:0-387-56470-5

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Rosenberg, E; Laine, R (1998). Concepts and models for characterizing homogeneous reactions catalyzed by transition metal cluster complexes. New York: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1–38. ISBN 0-471-23930-5.

- ↑ Jos de Jongh, L (1999). Physical properties of metal cluster compounds. Model systems for nanosized metal particles. New York: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1434–1453. ISBN 3-527-29549-6.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Martino, G (1979). "clusters: Models and precursors for metallic catalysts". Growth and Properties of Metal Clusters. Amsterdam: Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company. pp. 399–413. ISBN 0-444-41877-6.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Suss-Fink, G; Jahncke, M (1998). Synthesis of organic compounds catalyzed by transition metal clusters. New York: Wiley-VCH. pp. 167–248. ISBN 0-471-23930-5.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Calhorda, M; Braga, D; Grepioni, F (1999). Metal clusters - The relationship between molecular and crystal structure. New York: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1491–1508. ISBN 3-527-29549-6.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 <Douglas, Bodie; Darl McDaniel; John Alexander (1994). Concepts and Models of Inorganic Chemistry (third ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. pp. 816–887. ISBN 0-471-62978-2.

- ↑ 32.00 32.01 32.02 32.03 32.04 32.05 32.06 32.07 32.08 32.09 32.10 32.11 Braunstein, P; Rose, J (1998). Heterometallic clusters for heterogeneous catalysis. New York: Wiley-VCH. pp. 443–508. ISBN 0-471-23930-5.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 Smith, A; Basset, J (3 February 1977). "Transition metal cluster complexes as catalysts. A review". Journal of Molecular Catalysis 2 (4): 229–241. doi:10.1016/0304-5102(77)85011-6.

- ↑ Ichikawa, M; Rao, L; Kimura, T; Fukuoka, A (17 January 1990). "Transition Heterogenized bimetallic clusters: their structures and bifunctional catalysis". Journal of Molecular Catalysis 62 (1): 15–35. doi:10.1016/0304-5102(90)85236-B.

- ↑ Hugues, F; Bussiere, P; Basset, J; Commereuc, D; Chauvin, Y; Bonneviot, L; Olivier, D (1981). "Catalysis by supported clusters: Chemisorption, decomposition and catalytic properties in Fischer-Tropsch synthesis of Fe3(CO)12, [HFe3(CO)11]- (and Fe(CO)5) supported on highly divided oxides". Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis 7 (1): 418–431. doi:10.1016/S0167-2991(09)60288-3.

- ↑ Lavigne, G; de Bonneval, B (1998). Activation of ruthenium clusters for use in catalysis: Approaches and problems. New York: Wiley-VCH. pp. 39–94. ISBN 0-471-23930-5.

- ↑ Nakazawa, T; Igarashi, T; Tsuru, T; Kaji, Y (12 March 2009). "Ab initio calculations of Fe–Ni clusters". Computational Materials Science 46 (2): 367–375. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2009.03.012.

- ↑ Ma, Q999; Xie, Z; Wang, J; Liu, Y; Li, Y (4 January 2007). "Structures, binding energies and magnetic moments of small iron clusters: A study based on all-electron DFT". Solid State Communications 142 (1-2): 114–119. doi:10.1016/j.ssc.2006.12.023. Bibcode: 2007SSCom.142..114M.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Pacchioni, G; Kruger, S; Rosch, N (1999). Electronic structure of naked, ligated, and supported transition metal clusters from 'first principles' density functional theory. New York: Wiley-VCH. pp. 1392–1433. ISBN 3-527-29549-6.

- ↑ Andriotis, A; Lathiotakis, N; Menon, M (4 June 1996). "Magnetic properties of Ni and Fe clusters". Chemical Physics Letters 260 (1-2): 15–20. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(96)00850-0. Bibcode: 1996CPL...260...15A.

External links

- http://cluster-science.net - scientific community portal for clusters, fullerenes, nanotubes, nanostructures, and similar small systems