Chemistry:Maté (drink)

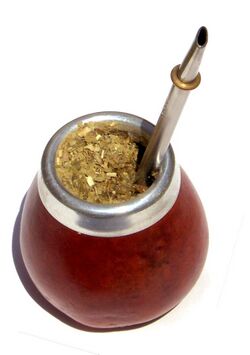

Maté in a traditional calabash gourd | |

| Type | Infusion, hot |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Paraguay |

| Introduced | Pre-Columbian era. First recorded by Spanish colonizers in the 15th century |

Maté or mate[note 1] (/ˈmæteɪ/),[2] also known as chimarrão or cimarrón,[note 2] is a traditional South American caffeine-rich infused drink, that was consumed by the Guaraní and Tupí peoples. It is the National Beverage in Argentina,[3] Uruguay and Paraguay. It is also consumed in the Bolivian Chaco, Southern Chile, Southern Brazil, Syria—the largest importer in the world—and Lebanon, where it was brought from Argentina by immigrants.[4][5]

It is prepared by steeping dried leaves of yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis, known in Portuguese as erva-mate) in hot water and is served with a metal straw from a shared hollow calabash gourd. The straw is called a bombilla in Spanish, a bomba in Portuguese, and a bombija or, more generally, a masassa (straw) in Arabic. The straw is traditionally made of silver. Modern, commercially available straws are typically made of nickel silver (called alpaca), stainless steel, or hollow-stemmed cane. The gourd is known as a mate or a guampa; while in Brazil, it has the specific name of cuia, or also cabaça (the name for Indigenous-influenced calabash gourds in other regions of Brazil, still used for general food and drink in remote regions). Even if the water is supplied from a modern thermos, the infusion is traditionally drunk from mates or cuias.

The maté leaves are dried, chopped, and ground into a powdery mixture called yerba, "erva" in Portuguese, which means "herb". The bombilla functions as both a straw and a sieve. The submerged end is flared, with small holes or slots that allow the brewed liquid in, but block the chunky matter that makes up much of the mixture. A modern bombilla design uses a straight tube with holes, or a spring sleeve to act as a sieve.[6]

"Tea-bag" type infusions of maté (Spanish: mate cocido, Portuguese: chá mate) have been on the market in many South American countries for many years under such trade names as "Taragüi" in Argentina, "Pajarito" and "Kurupí" in Paraguay, and Matte Leão and "Mate Real" in Brazil.

History

Maté was first consumed by the indigenous Guaraní and also spread by the Tupí people who lived in that part of southern Brazil and northeast Argentina, including some areas that were Paraguayan territory before the Paraguayan War. Therefore, the scientific name of the yerba-maté is Ilex paraguariensis. The consumption of yerba-mate became widespread with the European colonization in the Spanish colony of Paraguay in the late 16th century, among both Spanish settlers and indigenous Guaraní, who consumed it before the Spanish arrival. Maté consumption spread in the 17th century to the Río de la Plata and from there to Peru and Chile.[7] This widespread consumption turned it into Paraguay's main commodity above other wares such as tobacco, cotton and beef. Aboriginal labour was used to harvest wild stands. In the mid-17th century, Jesuits managed to domesticate the plant and establish plantations in their Indian reductions in the Argentine province of Misiones, sparking severe competition with the Paraguayan harvesters of wild strands. After their expulsion in the 1770s, the Jesuit missions — along with the yerba-maté plantations — fell into ruins. The industry continued to be of prime importance for the Paraguayan economy after independence, but development in benefit of the Paraguayan state halted after the Paraguayan War (1864–1870) that devastated the country both economically and demographically.

Brazil then became the largest producer of mate. In Brazilian and Argentine projects in late 19th and early 20th centuries, the plant was domesticated once again, opening the way for plantation systems. When Brazilian entrepreneurs turned their attention to coffee in the 1930s, Argentina, which had long been the prime consumer, took over as the largest producer, resurrecting the economy of Misiones Province, where the Jesuits had once had most of their plantations. For years, the status of largest producer shifted between Brazil and Argentina.[8]

Today, Argentina is the largest producer with 56–62%, followed by Brazil, 34–36%, and Paraguay, 5%.[9] Uruguay is the largest consumer per capita, consuming around 19 liters per year.[10]

Name

The English word comes from the French maté and the American Spanish mate, which means both maté and the vessel for drinking it, from the Quechua word mati for the vessel.[11][12]

Both the spellings "maté" and "mate" are used in English. The acute accent indicates that the word is pronounced with two syllables, like café (both maté and café are stressed on the first syllable in the UK), rather than like the one-syllable English word "mate".[13] An acute accent is not used in the Spanish spelling, because the first syllable is stressed and Spanish does not have silent letters. The Yerba Mate Association of the Americas points out that, in Spanish, "maté" with the stress on the second syllable means "I killed".[1]

In Brazil, traditionally prepared maté is known as chimarrão, although the word mate and the expression "mate amargo" (bitter maté) are also used in Argentina and Uruguay. The Spanish cimarrón means "rough", "brute", or "barbarian", but is most widely understood to mean "feral", and is used in almost all of Latin America for domesticated animals that have become wild. The word was then used by the people who colonized the region of the Río de la Plata to describe the natives' rough and sour drink, drunk with no other ingredient to soften the taste.

Culture

Maté has a strong cultural significance both in terms of national identity and well as socially. Maté is the national drink of Argentina;[14] Paraguay, where it is also consumed with either hot or ice cold water (see tereré);[15] and Uruguay. Drinking maté is a common social practice in parts of Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay and eastern Bolivia. Throughout the Southern Cone, it is considered to be a tradition taken from the gauchos or vaqueros, terms commonly used to describe the old residents of the South American pampas, chacos, or Patagonian grasslands, found principally in parts of Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, southeastern Bolivia, southern Chile and southern Brazil. Argentina has celebrated National Mate Day every 30 November since 2015.[citation needed]

Parque Histórico do Mate, funded by the state of Paraná (Brazil), is a park aimed to educate people on the sustainable harvesting methods needed to maintain the integrity and vitality of the oldest wild forests of maté in the world.[16][17]

Maté is also consumed as an iced tea in various regions of Brazil, originating both from an industrialized form, produced by Matte Leão, and from artisanal producers. It is part of the beach culture in Rio de Janeiro, where it is widely sold by beach vendors;[18] the hot infused variation being uncommon in the area.

Preparation

The preparation of maté is a simple process, consisting of filling a container with yerba, pouring hot, but not boiling, water over the leaves, and drinking with a straw, the bombilla, which acts as a filter so as to draw only the liquid and not the yerba leaves. The method of preparing the maté infusion varies considerably from region to region, and which method yields the finest outcome is debated. However, nearly all methods have some common elements. The beverage is traditionally prepared in a gourd recipient, also called mate or guampa in Spanish and cuia in Portuguese, from which it is drunk. The gourd is nearly filled with yerba, and hot water,[19] typically at 70 to 85 °C (158 to 185 °F), never boiling,[20] is added. The drink is so popular within countries that consume it, that several national electric kettle manufacturers just refer to the range 70 to 85 °C on its thermostat as "maté" temperature.[citation needed]

The most common preparation involves a careful arrangement of the yerba within the gourd before adding hot water. In this method, the gourd is first filled one-half to three-quarters of the way with yerba. Too much yerba will result in a "short" maté; conversely, too little yerba results in a "long" maté, both being considered undesirable. After that, any additional herbs (yuyo, in Portuguese jujo) may be added for either health or flavor benefits, a practice most common in Paraguay, where people acquire herbs from a local yuyera (herbalist) and use the maté as a base for their herbal infusions. When the gourd is adequately filled, the preparer typically grasps it with the full hand, covering and roughly sealing the opening with the palm. Then the maté is turned upside-down, and shaken vigorously, but briefly and with gradually decreasing force, in this inverted position. This causes the finest, most powdery particles of the yerba to settle toward the preparer's palm and the top of the maté.

Once the yerba mate has settled, the maté is carefully brought to a near-sideways angle, with the opening tilted just slightly upward of the base. The maté is then shaken very gently with a side-to-side motion. This further settles the yerba mate inside the gourd so that the finest particles move toward the opening and the yerba is layered along one side. The largest stems and other bits create a partition between the empty space on one side of the gourd and the lopsided pile of yerba on the other.

After arranging the yerba along one side of the gourd, the maté is carefully tilted back onto its base, minimizing further disturbances of the yerba as it is re-oriented to allow consumption. Some settling is normal, but is not desirable. The angled mound of yerba should remain, with its powdery peak still flat and mostly level with the top of the gourd. A layer of stems along its slope will slide downward and accumulate in the space opposite the yerba (though at least a portion should remain in place).

All of this careful settling of the yerba ensures that each sip contains as little particulate matter as possible, creating a smooth-running maté. The finest particles will then be as distant as possible from the filtering end of the straw. With each draw, the smaller particles would inevitably move toward the straw, but the larger particles and stems filter much of this out. A sloped arrangement provides consistent concentration and flavor with each filling of the maté.

Now the maté is ready to receive the straw. Wetting the yerba by gently pouring cool water into the empty space within the gourd until the water nearly reaches the top, and then allowing it to be absorbed into the yerba before adding the straw, allows the preparer to carefully shape and "pack" the yerba's slope with the straw's filtering end, which makes the overall form of the yerba within the gourd more resilient and solid. Dry yerba, though, allows a cleaner and easier insertion of the straw, but care must be taken so as not to overly disturb the arrangement of the yerba. Such a decision is entirely a personal or cultural preference. The straw is inserted with one's thumb on the upper end of the gourd, at an angle roughly perpendicular to the slope of the yerba, so that its filtering end travels into the deepest part of the yerba and comes to rest near or against the opposite wall of the gourd. It is important for the thumb to form a seal over the end of the straw when it is being inserted, or the negative pressure produced will draw in undesirable particulates.

Brewing

After the above process, the yerba may be brewed. If the straw is inserted into dry yerba, the maté must first be filled once with cool water as above, then be allowed to absorb it completely (which generally takes no more than two or three minutes). Treating the yerba with cool water before the addition of hot water is essential, as it protects the yerba mate from being scalded and from the chemical breakdown of some of its desirable nutrients. Hot water may then be added by carefully pouring it, as with the cool water before, into the cavity opposite the yerba, until it reaches almost to the top of the gourd when the yerba is fully saturated. Care should be taken to maintain the dryness of the swollen top of the yerba beside the edge of the gourd's opening.

Once the hot water has been added, the maté is ready for drinking, and it may be refilled many times before becoming lavado (washed out) and losing its flavor. When this occurs, the mound of yerba can be pushed from one side of the gourd to the other, allowing water to be added along its opposite side; this revives the maté for additional refillings and is called "reformar o/el mate" (reforming the maté).

Etiquette

Maté is traditionally drunk in a particular social setting, such as family gatherings or with friends. The same gourd (cuia) and straw (bomba/bombilla) are used by everyone drinking. One person (known in Portuguese as the preparador, cevador, or patrão, and in Spanish as the cebador) assumes the task of server. Typically, the cebador fills the gourd and drinks the maté completely to ensure that it is free of particulate matter and of good quality. In some places, passing the first brew of maté to another drinker is considered bad manners, as it may be too cold or too strong; for this reason, the first brew is often called mate del zonzo (mate of the fool). The cebador possibly drinks the second filling, as well, if he or she deems it too cold or bitter. The cebador subsequently refills the gourd and passes it to the drinker to his or her right, who likewise drinks it all (there is not much; the maté is full of yerba, with room for little water), and returns it without thanking the server; a final gracias (thank you) implies that the drinker has had enough.[21] The only exception to this order is if a new guest joins the group; in this case the new arrival receives the next maté, and then the cebador resumes the order of serving, and the new arrival will receive his or hers depending on his placement in the group. When no more tea remains, the straw makes a loud sucking noise, which is not considered rude. The ritual proceeds around the circle in this way until the maté becomes lavado (washed out), typically after the gourd has been filled about 10 times or more depending on the yerba used (well-aged yerba mate is typically more potent, so provides a greater number of refills) and the ability of the cebador. When one has had one's fill of maté, he or she politely thanks the cebador, passing the maté back at the same time. It is impolite for anyone but the cebador to move the bombilla or otherwise mess with the maté; the cebador may take offense to this and not offer it to the offender again. When someone takes too long, others in the round (roda in Portuguese, ronda in Spanish) will likely politely warn him or her by saying "bring the talking gourd" (cuia de conversar); an Argentine equivalent, especially among young people, being no es un micrófono ("it's not a microphone"), an allusion to the drinkers holding the maté for too long, as if they were using it as a microphone to deliver a lecture.

Some drinkers like to add sugar or honey, creating mate dulce or mate doce (sweet maté), instead of sugarless mate amargo (bitter maté), a practice said to be more common in Brazil outside its southernmost state. Some people also like to add lemon or orange peel, some herbs or even coffee, but these are mostly rejected by people who like to stick to the "original" maté. Traditionally, natural gourds are used, though wood vessels, bamboo tubes, and gourd-shaped mates, made of ceramic or metal (stainless steel or even silver) are also common. The gourd is traditionally made out of the porongo or cabaça fruit shell. Gourds are commonly decorated with silver, sporting decorative or heraldic designs with floral motifs. Some gourd mates with elaborated silver ornaments and silver bombillas are true pieces of jewelry and very sought after by collectors.

Health effects

A review of a number of population studies in 2009 revealed evidence of an association between esophageal cancer and hot maté drinking, but these population studies may not be conclusive.[22] Some research has suggested the correlation with esophageal cancer results almost entirely from damage caused to the esophagus by burns from the hot liquid as opposed to damage caused by chemicals in the maté; similar links to cancer have been found for tea and other beverages generally consumed at high temperatures. While drinking maté at very high temperatures is considered as "probably carcinogenic to humans" on the IARC Group 2A carcinogens list, maté itself is not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans.[23]

Researchers from NCI (National Cancer Institutes) and Brazil found both cold- and hot-water extractions of popular commercial yerba-maté products contained high levels (8.03 to 53.3 ng/g dry leaves) of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (i.e. benzo[a]pyrene).[24] However, these potential carcinogenic compounds originated from the commercial drying process of the maté leaves, which involves smoke from the burning of wood, much like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons found in wood-smoked meat.[25] "Unsmoked" or steamed varieties of yerba-maté tea are also available.[26]

Other properties

Maté is a rich source of caffeine, although in some regions it was believed to contain a different substance called mateína (matein or mateine). It also contains B and C vitamins, polyphenol antioxidants, and has a slightly higher antioxidant capacity than green tea. On average, maté tea contains 92 mg of the antioxidant chlorogenic acid per gram of dry leaves, and no catechins, giving it a significantly different antioxidant profile from other teas.[27][28]

Legendary origins

The Guaraní people started drinking maté in a region that currently includes Paraguay, southern Brazil, southeastern Bolivia, northeastern Argentina and Uruguay. The Guaraní have a legend that says the Goddesses of the Moon and the Cloud came to the Earth one day to visit it, but they instead found a yaguareté (jaguar) that was going to attack them. An old man saved them, and, in compensation, the goddesses gave the old man a new kind of plant, from which he could prepare a "drink of friendship".

Variants

Another drink can be prepared with specially cut dry leaves, very cold water, and, optionally, lemon or another fruit juice, called tereré. It is very common in Paraguay, northeastern Argentina and in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. After pouring the water, it is considered proper to "wait while the saint has a sip" before the first person takes a drink. In southern Brazil, tererê is sometimes used as a derogatory term for a not hot enough chimarrão.

In Uruguay and Brazil, the traditional gourd is usually big with a corresponding large hole. In Argentina (especially in the capital Buenos Aires), the gourd is small and has a small hole and people sometimes add sugar for flavor.

In Uruguay, people commonly walk around the streets toting a maté and a thermos with hot water. In some parts of Argentina, gas stations sponsored by yerba mate producers provide free hot water to travelers, specifically for the purpose of drinking during the journey. Disposable maté sets with a plastic maté and straw and sets with a thermos flask and stacking containers for the yerba and sugar inside a fitted case are available.

In Argentina, mate cocido (boiled maté), in Brazil, "chá mate", is made with a teabag or leaves and drunk from a cup or mug, with or without sugar and milk. Companies such as Cabrales from Mar del Plata and Establecimiento Las Marías produce teabags for export to Europe.[29]

Travel narratives, such as Maria Graham's Journal of a Residence in Chile, show a long history of maté drinking in central Chile. Many rural Chileans drink maté, in particular in the southern regions, particularly Magallanes, Aysén and Chiloé.

In Peru, maté is widespread throughout the north and south, first being introduced to Lima in the 17th century. It is widespread in rural zones, and it is prepared with coca (plant) or in a sweetened tea form with small slices of lemon or orange.[30]

In some parts of Syria, Lebanon and other Eastern Mediterranean countries, drinking maté is common. The custom came from Syrians and Lebanese who moved to South America during the late 19th and early parts of the 20th century, adopted the tradition, and kept it after returning to Western Asia. Syria is the biggest importer of yerba-maté in the world, importing 15,000 tons a year. Mostly, the Druze communities in Syria and Lebanon maintain the culture and practice of maté.[4][5]

According to a major retailer of maté in San Luis Obispo, California , by 2004, maté had grown to about 5% of the overall natural tea market in North America.[31][32] Loose maté is commercially available in much of North America. Bottled maté is increasingly available in the United States. Canadian bottlers have introduced a cane sugar-sweetened, carbonated variety, similar to soda pop. One brand, Sol Mate, produces 10-ounce glass bottles available at Canadian and U.S. retailers, making use of the translingual pun (English 'soul mate'; Spanish/Portuguese 'sun mate') for the sake of marketing.[33]

In some parts of the Southern Cone they prefer to drink bitter maté, especially in Paraguay, Uruguay, the south of Brazil, and parts of Argentina and Bolivia. This is referred to in Brazil and a large part of Argentina as cimarrón – which also an archaic name for wild cattle, especially, to a horse that was very attached to a cowboy—which is understood as unsweetened maté.[34] Many people are of the opinion that maté should be drunk in this form.

Unlike bitter maté, in every preparation of mate dulce, or sweet maté, sugar is incorporated according to the taste of the drinker. This form of preparation is very widespread in various regions of Argentina , like in the Santiago del Estero province, Córdoba (Argentina), Cuyo, and the metropolitan region of Buenos Aires, among others. In Chile, this form of maté preparation is widespread in mostly rural zones. The spoonful of sugar or honey should fall on the edge of the cavity that the straw forms in the yerba, not all over the maté. One variation is to sweeten only the first maté preparation in order to cut the bitterness of the first sip, thus softening the rest. In Paraguay, a variant of mate dulce is prepared by first caramelizing refined sugar in a pot then adding milk. The mixture is heated and placed in a thermos and used in place of water. Often, chamomile (manzanilla, in Spanish) and coconut are added to yerba in the gumpa.

In the sweet version artificial sweeteners are also often added. As an alternative sweetener, natural ka’á he’é (Stevia rebaudiana) is preferred, which is an herb whose leaves are added in order to give a touch of sweetness. This is used principally in Paraguay.

The gourd in which bitter maté is drunk is not used to consume sweet maté due to the idea that the taste of the sugar would be detrimental to its later use to prepare and drink bitter maté, as it is said that it ruins the flavor of the maté.[35]

Notes

- ↑ Both the "maté" and "mate" spellings are common in English.

In Spanish and Portuguese, it is spelled "mate" without the accent. The pronunciation is [ˈmate] in Spanish and [ˈmatʃi] in Portuguese.[1] - ↑ Portuguese: [ʃimɐˈʁɐ̃w̃]; Spanish: [simaˈron]

See also

- Black drink

- Mate con malicia (Chilean beverage)

- Ilex guayusa (caffeinated beverage made from another holly tree)

- List of Brazilian dishes

- Mate de coca

- Club-Mate

- Materva

- Guayakí

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Mate - beverage". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/topic/mate-beverage. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ maté (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, September 2005, http://oed.com/search?searchType=dictionary&q=mat%C3%A9 (Subscription or UK public library membership required.).

Also US: /ˈmɑːteɪ/ "Maté". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mat%C3%A9. - ↑ "Ley 26.871 - Declárase al Mate como infusión nacional." (in Spanish). InfoLEG. Ministry of Economy and Public Finance. http://www.infoleg.gob.ar/infolegInternet/anexos/215000-219999/218040/norma.htm. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Barceloux, Donald (3 February 2012). Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-11810-605-1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "South American 'mate' tea a long-time Lebanese hit". Middle East Online. http://www.middle-east-online.com/english/?id=64763. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ↑ Goodfriend, Anne (2 March 2006). "Yerba maté: The accent is on popular health drink". USA Today: p. 1. https://www.usatoday.com/travel/destinations/2006-03-02-yerba-mate_x.htm. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Regional History of Yerba Mate". https://www.yerba-mate.com/yerba_mate_history.htm.

- ↑ "History of Mate". Establecimiento Las Marías. http://comex.lasmarias.com.ar/eng/detalle.php?a=yerba-mate-tea&t=3&d=1. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ↑ "segundoenfoque". 9 February 2018. http://segundoenfoque.com/la-produccion-yerba-mate-argentina-registro-record-historico-2018-02-09. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "As Consumption Stagnates in South America, will Yerba Mate Move North?". 19 October 2016. http://blog.euromonitor.com/2016/10/as-consumption-stagnates-in-south-america-will-yerba-mate-move-north.html. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ↑ "Maté". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mat%C3%A9.

- ↑ Etymology of maté in the Trésor de la langue française informatisé

- ↑ Although the order of spelling variants in dictionaries is not necessarily meaningful in any particular case, Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged, the Oxford English Dictionary, Collins English Dictionary, the Random House Dictionary of the English Language and Lexico.com all give the accented form "maté" before the unaccented form "mate", or refer the reader to see "maté" if they look up "mate".

- ↑ Sanders, Kerry. "Next time you're in Argentina, try a cup of mate". MSNBC. p. 1. http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/24315283/ns/today-where_in_the_world/t/next-time-youre-argentina-try-cup-mate/. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ Conran, Caroline, Conran, Terence, and Hopkinson, Simon (2001). The Conran Cookbook. Conran-Octopus. ISBN 978-1-84091-182-4.

- ↑ "Museu Paranaense". Museuparanaense.pr.gov.br. http://www.museuparanaense.pr.gov.br/modules/conteudo/conteudo.php?conteudo=56. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ "Nativa Yerba Mate". http://www.nativayerbamate/harvest.html. Retrieved 18 July 2011.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Barrionuevo, Alexei (9 February 2010). "Clamping Down on the Kaleidoscope of Rio's Beaches". The New York Times (New York City). https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/10/world/americas/10rio.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ Brooke, Elizabeth (24 April 1991). "Yerba Mate, Ancient Antidote To South America's Heat". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1991/04/24/garden/yerba-mate-ancient-antidote-to-south-america-s-heat.html. Retrieved 28 May 2011.

- ↑ "Traditional Method". http://www.ma-tea.com/pages/Traditional-Method.html. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ La Nación newspaper: ¿Se toma un mate? (Segunda parte) (in Spanish)

- ↑ Loria, D.; Barrios E; Zanetti R. (June 2009). "Cancer and Yerba Mate Consumption: a Review of Possible Associations". Rev Panam Salud Publica 25 (6; June): 530–9. doi:10.1590/S1020-49892009000600010. PMID 19695149. (Full Free Text)

- ↑ Mate (IARC Summary & Evaluation). 51. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 1991. p. 273. http://www.inchem.org/documents/iarc/vol51/03-mate.html.

- ↑ Kamangar, F.; Schantz, M. M.; Abnet, C. C.; Fagundes, R. B.; Dawsey, S. M. (2008). "High Levels of Carcinogenic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Mate Drinks". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention (Cebp.aacrjournals.org) 17 (5): 1262–1268. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0025. PMID 18483349. http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/17/5/1262. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ Yerba mate: Pharmacological Properties Research and Biotechnology [|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Yerba mate drinking methods". 2011. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110126142842/http://yerbamate.com/drying-methods/. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Heck, C. I.; De Mejia, E. G. (17 October 2007). "Yerba Mate Tea: A Comprehensive Review on Chemistry, Health Implications, and Technological Considerations". Journal of Food Science 72 (9): R138-51. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00535.x. PMID 18034743.

- ↑ Heck, C. I.; De Mejia, E. G. (17 October 2007). "Polyphenols in green tea, black tea, and Mate tea". Journal of Food Science 72 (9): R138–R151. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00535.x. PMID 18034743.

- ↑ Cabrales abrirá locales en la Capital La Nación online, 6 October 2001 (in Spanish)

- ↑ Villanueva, Amaro (1960). EL MATE Arte de Cebar. Buenos Aires: La compañia general fabril financiera S. A.. pp. 200 (In Spanish).

- ↑ "Guayaki Honored With 2004 Socially Responsible Business Award" (Press release). Guayaki. 28 October 2004.

- ↑ Everage, Laura (1 November 2004). "Trends in Tea". The Gourmet Retailer. Archived from the original on 5 November 2006. https://web.archive.org/web/20061105141723/http://www.gourmetretailer.com/gourmetretailer/magazine/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1000696346.

- ↑ Rude, Justin (19 January 2007). "Tip Sheet: Lowdown on Liquid Power-Ups". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/graphic/2007/01/19/GR2007011900577.html. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- ↑ "Mate Terms and Glossary". https://circleofdrink.com/yerba-mate-terms-and-glossary.

- ↑ SMITH, JAMES F. (10 August 1988). "More Than a Drink : Yerba Mate: Argentina's Cultural Rite". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. http://articles.latimes.com/1988-08-10/news/mn-143_1_yerba-mate-cultivation/2.

External links

Bibliography

- Assunção, Fernando O. (1967) (in es). El mate. Bolsilibros Arca.