Biology:Jaguar

| Jaguar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. onca

|

| Binomial name | |

| Panthera onca | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Current range

Former range | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The jaguar (Panthera onca) is a large cat species and the only living member of the genus Panthera native to the Americas. With a body length of up to 1.85 m (6 ft 1 in) and a weight of up to 158 kg (348 lb), it is the biggest cat species in the Americas and the third largest in the world. Its distinctively marked coat features pale yellow to tan colored fur covered by spots that transition to rosettes on the sides, although a melanistic black coat appears in some individuals. The jaguar's powerful bite allows it to pierce the carapaces of turtles and tortoises, and to employ an unusual killing method: it bites directly through the skull of mammalian prey between the ears to deliver a fatal blow to the brain.

The modern jaguar's ancestors probably entered the Americas from Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene via the land bridge that once spanned the Bering Strait. Today, the jaguar's range extends from the Southwestern United States across Mexico and much of Central America, the Amazon rainforest and south to Paraguay and northern Argentina . It inhabits a variety of forested and open terrains, but its preferred habitat is tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forest, wetlands and wooded regions. It is adept at swimming and is largely a solitary, opportunistic, stalk-and-ambush apex predator. As a keystone species, it plays an important role in stabilizing ecosystems and in regulating prey populations.

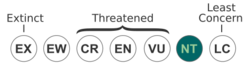

The jaguar is threatened by habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, poaching for trade with its body parts and killings in human–wildlife conflict situations, particularly with ranchers in Central and South America. It has been listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List since 2002. The wild population is thought to have declined since the late 1990s. Priority areas for jaguar conservation comprise 51 Jaguar Conservation Units (JCUs), defined as large areas inhabited by at least 50 breeding jaguars. The JCUs are located in 36 geographic regions ranging from Mexico to Argentina.

The jaguar has featured prominently in the mythology of indigenous peoples of the Americas, including those of the Aztec and Maya civilizations.

Etymology

The word "jaguar" is possibly derived from the Tupi-Guarani word yaguara meaning 'wild beast that overcomes its prey at a bound'.[3][4][better source needed] In North America, the word is pronounced disyllabic /ˈdʒæɡwɑːr/, while in British English, it is pronounced with three syllables /ˈdʒæɡjuːər/.[5][6] Because that word also applies to other animals, indigenous peoples in Guyana call it jaguareté, with the added sufix eté, meaning "true beast".[7] "Onca" is derived from the Portuguese name onça for a spotted cat that is larger than a lynx; cf. ounce.[8] The word "panther" is derived from classical Latin panthēra, itself from the ancient Greek πάνθηρ (pánthēr).[9]

Taxonomy and evolution

Taxonomy

In 1758, Carl Linnaeus described the jaguar in his work Systema Naturae and gave it the scientific name Felis onca.[10]

In the 19th and 20th centuries, several jaguar type specimens formed the basis for descriptions of subspecies.[2] In 1939, Reginald Innes Pocock recognized eight subspecies based on the geographic origins and skull morphology of these specimens.[11] Pocock did not have access to sufficient zoological specimens to critically evaluate their subspecific status but expressed doubt about the status of several. Later consideration of his work suggested only three subspecies should be recognized. The description of P. o. palustris was based on a fossil skull.[4]

By 2005, nine subspecies were considered to be valid taxa:[2]

- P. o. onca (Linnaeus, 1758) was a jaguar from Brazil.[10]

- P. o. peruviana (De Blainville, 1843) was a jaguar skull from Peru.[12]

- P. o. hernandesii (Gray, 1857) was a jaguar from Mazatlán in Mexico.[13]

- P. o. palustris (Ameghino, 1888) was a fossil jaguar mandible excavated in the Sierras Pampeanas of Córdova District, Argentina.[14]

- P. o. centralis (Mearns, 1901) was a skull of a male jaguar from Talamanca, Costa Rica.[15]

- P. o. goldmani (Mearns, 1901) was a jaguar skin from Yohatlan in Campeche, Mexico.[15]

- P. o. paraguensis (Hollister, 1914) was a skull of a male jaguar from Paraguay.[16]

- P. o. arizonensis (Goldman, 1932) was a skin and skull of a male jaguar from the vicinity of Cibecue, Arizona.[17]

- P. o. veraecrucis (Nelson and Goldman, 1933) was a skull of a male jaguar from San Andrés Tuxtla in Mexico.[18]

Reginald Innes Pocock placed the jaguar in the genus Panthera and observed that it shares several morphological features with the leopard (P. pardus). He, therefore, concluded that they are most closely related to each other.[11] Results of morphological and genetic research indicate a clinal north–south variation between populations, but no evidence for subspecific differentiation.[19][20] DNA analysis of 84 jaguar samples from South America revealed that the gene flow between jaguar populations in Colombia was high in the past.[21] Since 2017, the jaguar is considered to be a monotypic taxon,[22] though the modern Panthera onca onca is still distinguished from two fossil subspecies, Panthera onca augusta and Panthera onca mesembrina.

Evolution

The Panthera lineage is estimated to have genetically diverged from the common ancestor of the Felidae around 9.32 to 4.47 million years ago to 11.75 to 0.97 million years ago.[23][24][25] Some genetic analyses place the jaguar as a sister species to the lion with which it diverged 3.46 to 1.22 million years ago,[23][24] but other studies place the lion closer to the leopard.[26][27]

The lineage of the jaguar appears to have originated in Africa and spread to Eurasia 1.95–1.77 mya. The modern species may have descended from Panthera gombaszoegensis, which is thought to have entered the American continent via Beringia, the land bridge that once spanned the Bering Strait.[28][29] Fossils of modern jaguars have been found in North America dating to over 850,000 years ago.[4] Results of mitochondrial DNA analysis of 37 jaguars indicate that current populations evolved between 510,000 and 280,000 years ago in northern South America and subsequently recolonized North and Central America after the extinction of jaguars there during the Late Pleistocene.[19]

Two extinct subspecies of jaguar are recognized in the fossil record: the North American P. o. augusta and South American P. o. mesembrina.[30] Script error: No such module "Clade/gallery".

Description

The jaguar is a compact and muscular animal. It is the largest cat native to the Americas and the third largest in the world, exceeded in size only by the tiger and the lion.[4][31][32] It stands 57 to 81 cm (22.4 to 31.9 in) tall at the shoulders.[33][34] Its size and weight vary considerably depending on sex and region: weights in most regions are normally in the range of 56–96 kg (123–212 lb). Exceptionally big males have been recorded to weigh as much as 158 kg (348 lb).[35][36] The smallest females from Middle America weigh about 36 kg (79 lb). It is sexually dimorphic, with females typically being 10–20% smaller than males. The length from the nose to the base of the tail varies from 1.12 to 1.85 m (3 ft 8 in to 6 ft 1 in). The tail is 45 to 75 cm (18 to 30 in) long and the shortest of any big cat.[35] Its muscular legs are shorter than the legs of other Panthera species with similar body weight.[37]

Size tends to increase from north to south. Jaguars in the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve on the Pacific coast of central Mexico weighed around 50 kg (110 lb).[38] Jaguars in Venezuela and Brazil are much larger, with average weights of about 95 kg (209 lb) in males and of about 56–78 kg (123–172 lb) in females.[4]

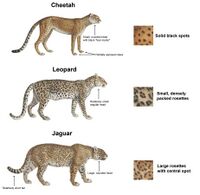

The jaguar's coat ranges from pale yellow to tan or reddish-yellow, with a whitish underside and covered in black spots. The spots and their shapes vary: on the sides, they become rosettes which may include one or several dots. The spots on the head and neck are generally solid, as are those on the tail where they may merge to form bands near the end and create a black tip. They are elongated on the middle of the back, often connecting to create a median stripe, and blotchy on the belly.[4] These patterns serve as camouflage in areas with dense vegetation and patchy shadows.[39] Jaguars living in forests are often darker and considerably smaller than those living in open areas, possibly due to the smaller numbers of large, herbivorous prey in forest areas.[40]

The jaguar closely resembles the leopard but is generally more robust, with stockier limbs and a more square head. The rosettes on a jaguar's coat are larger, darker, fewer in number and have thicker lines, with a small spot in the middle.[37] It has powerful jaws with the third-highest bite force of all felids, after the tiger and the lion.[41] It has an average bite force at the canine tip of 887.0 Newton and a bite force quotient at the canine tip of 118.6.[42] A 100 kg (220 lb) jaguar can bite with a force of 4.939 kN (1,110 lbf) with the canine teeth and 6.922 kN (1,556 lbf) at the carnassial notch.[43]

Color variation

Melanistic jaguars are also known as black panthers. The black morph is less common than the spotted one.[44] Black jaguars have been documented in Central and South America. Melanism in the jaguar is caused by deletions in the melanocortin 1 receptor gene and inherited through a dominant allele.[45] Black jaguars occur at higher densities in tropical rainforest and are more active during the daytime. This suggests that melanism provides camouflage in dense vegetation with high illumination.[46]

In 2004, a camera trap in the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains photographed the first documented black jaguar in Northern Mexico.[47] Black jaguars were also photographed in Costa Rica's Alberto Manuel Brenes Biological Reserve, in the mountains of the Cordillera de Talamanca, in Barbilla National Park and in eastern Panama.[48][46][49][50]

Distribution and habitat

In 1999, the jaguar's historic range at the turn of the 20th century was estimated at 19,000,000 km2 (7,300,000 sq mi), stretching from the southern United States through Central America to southern Argentina. By the turn of the 21st century, its global range had decreased to about 8,750,000 km2 (3,380,000 sq mi), with most declines in the southern United States, northern Mexico, northern Brazil, and southern Argentina.[51] Its present range extends from Mexico through Central America to South America comprising Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, particularly on the Osa Peninsula, Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina . It is considered to be locally extinct in El Salvador and Uruguay.[1]

Jaguars have been occasionally sighted in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas .[52][53] Between 2012 and 2015, a male vagrant jaguar was recorded in 23 locations in the Santa Rita Mountains.[54]

The jaguar prefers dense forest and typically inhabits dry deciduous forests, tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests, rainforests and cloud forests in Central and South America; open, seasonally flooded wetlands, dry grassland and historically also oak forests in the United States. It has been recorded at elevations up to 3,800 m (12,500 ft) but avoids montane forests. It favors riverine habitat and swamps with dense vegetation cover.[40] In the Mayan forests of Mexico and Guatemala, 11 GPS-collared jaguars preferred undisturbed dense habitat away from roads; females avoided even areas with low levels of human activity, whereas males appeared less disturbed by human population density.[55] A young male jaguar was also recorded in the semi-arid Sierra de San Carlos at a waterhole.[56]

Former range

In the 19th century, the jaguar was still sighted at the North Platte River 48–80 km (30–50 mi) north of Longs Peak in Colorado, in coastal Louisiana, northern Arizona and New Mexico.[57] Multiple verified zoological reports of the jaguar are known in California, two as far north as Monterey in 1814 and 1826. The only record of an active jaguar den with breeding adults and kittens in the United States was in the Tehachapi Mountains of California prior to 1860.[58] The jaguar persisted in California until about 1860.[53] The last confirmed jaguar in Texas was shot in 1948, 4.8 km (3 mi) southeast of Kingsville, Texas.[59] In Arizona, a female was shot in the White Mountains in 1963. By the late 1960s, the jaguar was thought to have been extirpated in the United States. Arizona outlawed jaguar hunting in 1969, but by then no females remained, and over the next 25 years only two males were sighted and killed in the state. In 1996, a rancher and hunting guide from Douglas, Arizona came across a jaguar in the Peloncillo Mountains and became a researcher on jaguars, placing trail cameras, which recorded four more jaguars.[60]

Behavior and ecology

The jaguar is mostly active at night and during twilight.[34][61][62] However, jaguars living in densely forested regions of the Amazon Rainforest and the Pantanal are largely active by day, whereas jaguars in the Atlantic Forest are primarily active by night.[63] The activity pattern of the jaguar coincides with the activity of its main prey species.[64] Jaguars are good swimmers and play and hunt in the water, possibly more than tigers. They have been recorded moving between islands and the shore. Jaguars are also good at climbing trees but do so less often than cougars.[4]

Ecological role

The adult jaguar is an apex predator, meaning it is at the top of the food chain and is not preyed upon in the wild. The jaguar has also been termed a keystone species, as it is assumed that it controls the population levels of prey such as herbivorous and seed-eating mammals and thus maintains the structural integrity of forest systems.[38][65][66] However, field work has shown this may be natural variability, and the population increases may not be sustained. Thus, the keystone predator hypothesis is not accepted by all scientists.[67]

The jaguar is sympatric with the cougar (Puma concolor). In central Mexico, both prey on white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), which makes up 54% and 66% of jaguar and cougar's prey, respectively.[38] In northern Mexico, the jaguar and the cougar share the same habitat, and their diet overlaps dependent on prey availability. Jaguars seemed to prefer deer and calves. In Mexico and Central America, neither of the two cats are considered to be the dominant predator.[68] In South America, the jaguar is larger than the cougar and tends to take larger prey, usually over 22 kg (49 lb). The cougar's prey usually weighs between 2 and 22 kg (4 and 49 lb), which is thought to be the reason for its smaller size.[69] This situation may be advantageous to the cougar. Its broader prey niche, including its ability to take smaller prey, may give it an advantage over the jaguar in human-altered landscapes.[38]

Hunting and diet

The jaguar is an obligate carnivore and depends solely on flesh for its nutrient requirements. An analysis of 53 studies documenting the diet of the jaguar revealed that its prey ranges in weight from 1 to 130 kg (2.2 to 286.6 lb); it prefers prey weighing 45–85 kg (99–187 lb), with the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) and the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) being the most selected. When available, it also preys on marsh deer (Blastocerus dichotomus), southern tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla), collared peccary (Dicotyles tajacu) and black agouti (Dasyprocta fuliginosa).[31] In floodplains, jaguars opportunistically take reptiles such as turtles and caimans. Consumption of reptiles appears to be more frequent in jaguars than in other big cats.[70] One remote population in the Brazilian Pantanal is recorded to primarily feed on aquatic reptiles and fish.[71] The jaguar also preys on livestock in cattle ranching areas where wild prey is scarce.[72][73] The daily food requirement of a captive jaguar weighing 34 kg (75 lb) was estimated at 1.4 kg (3.1 lb) of meat.[74]

The jaguar's bite force allows it to pierce the carapaces of the yellow-spotted Amazon river turtle (Podocnemis unifilis) and the yellow-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis denticulatus).[74][75] It employs an unusual killing method: it bites mammalian prey directly through the skull between the ears to deliver a fatal bite to the brain.[76] It kills capybara by piercing its canine teeth through the temporal bones of its skull, breaking its zygomatic arch and mandible and penetrating its brain, often through the ears.[77] It has been hypothesized to be an adaptation to cracking open turtle shells; armored reptiles may have formed an abundant prey base for the jaguar following the late Pleistocene extinctions.[74] However, this is disputed, as even in areas where jaguars prey on reptiles, they are still taken relatively infrequently compared to mammals in spite of their greater abundance.[70]

Between October 2001 and April 2004, 10 jaguars were monitored in the southern Pantanal. In the dry season from April to September, they killed prey at intervals ranging from one to seven days; and ranging from one to 16 days in the wet season from October to March.[78]

The jaguar uses a stalk-and-ambush strategy when hunting rather than chasing prey. The cat will slowly walk down forest paths, listening for and stalking prey before rushing or ambushing. The jaguar attacks from cover and usually from a target's blind spot with a quick pounce; the species' ambushing abilities are considered nearly peerless in the animal kingdom by both indigenous people and field researchers and are probably a product of its role as an apex predator in several different environments. The ambush may include leaping into water after prey, as a jaguar is quite capable of carrying a large kill while swimming; its strength is such that carcasses as large as a heifer can be hauled up a tree to avoid flood levels. After killing prey, the jaguar will drag the carcass to a thicket or other secluded spot. It begins eating at the neck and chest. The heart and lungs are consumed, followed by the shoulders.[79]

Social activity

The jaguar is generally solitary except for females with cubs. In 1977, groups consisting of a male, female and cubs, and two females with two males were sighted several times in a study area in the Paraguay River valley.[80] In some areas, males may form paired coalitions which together mark, defend and invade territories, find and mate with the same females and search for and share prey.[81] A radio-collared female moved in a home range of 25–38 km2 (9.7–14.7 sq mi), which partly overlapped with another female. The home range of the male in this study area overlapped with several females.[80]

The jaguar uses scrape marks, urine, and feces to mark its territory.[82][83] The size of home ranges depends on the level of deforestation and human population density. The home ranges of females vary from 15.3 km2 (5.9 sq mi) in the Pantanal to 53.6 km2 (20.7 sq mi) in the Amazon to 233.5 km2 (90.2 sq mi) in the Atlantic Forest. Male jaguar home ranges vary from 25 km2 (9.7 sq mi) in the Pantanal to 180.3 km2 (69.6 sq mi) in the Amazon to 591.4 km2 (228.3 sq mi) in the Atlantic Forest and 807.4 km2 (311.7 sq mi) in the Cerrado.[84] Studies employing GPS telemetry in 2003 and 2004 found densities of only six to seven jaguars per 100 km (62 mi) in the Pantanal region, compared with 10 to 11 using traditional methods; this suggests the widely used sampling methods may inflate the actual numbers of individuals in a sampling area.[85] Fights between males occur but are rare, and avoidance behavior has been observed in the wild.[82] In one wetland population with degraded territorial boundaries and more social proximity, adults of the same sex are more tolerant of each other and engage in more friendly and co-operative interactions.[71]

File:Jaguar saw.flac The jaguar roars/grunts for long-distance communication;[4][74] intensive bouts of counter-calling between individuals have been observed in the wild.[74] This vocalization is described as "hoarse" with five or six guttural notes.[4] Chuffing is produced by individuals when greeting, during courting, or by a mother comforting her cubs. This sound is described as low intensity snorts, possibly intended to signal tranquility and passivity.[86][87] Cubs have been recorded bleating, gurgling and mewing.[4]

Reproduction and life cycle

In captivity, the female jaguar is recorded to reach sexual maturity at the age of about 2.5 years. Estrus lasts 7–15 days with an estrus cycle of 41.8 to 52.6 days. During estrus, she exhibits increased restlessness with rolling and prolonged vocalizations.[88] She is an induced ovulator but can also ovulate spontaneously.[89][90] Gestation lasts 91 to 111 days.[91] The male is sexually mature at the age of three to four years.[92] His mean ejaculate volume is 8.6±1.3 ml.[93] Generation length of the jaguar is 9.8 years.[94]

In the Pantanal, breeding pairs were observed to stay together for up to five days. Females had one to two cubs.[95] The young are born with closed eyes but open them after two weeks. Cubs are weaned at the age of three months but remain in the birth den for six months before leaving to accompany their mother on hunts.[96] Jaguars remain with their mothers for up to two years. They appear to rarely live beyond 11 years, but captive individuals may live 22 years.[4]

In 2001, a male jaguar killed and partially consumed two cubs in Emas National Park. DNA paternity testing of blood samples revealed that the male was the father of the cubs.[97] Two more cases of infanticide were documented in the northern Pantanal in 2013.[98] To defend against infanticide, the female may hide her cubs and distract the male with courtship behavior.[99]

Attacks on humans

The Spanish conquistadors feared the jaguar. According to Charles Darwin, the indigenous peoples of South America stated that people did not need to fear the jaguar as long as capybaras were abundant.[100] The first official record of a jaguar killing a human in Brazil dates to June 2008.[101] Two children were attacked by jaguars in Guyana.[102] The majority of known attacks on people happened when it had been cornered or wounded.[103]

Threats

The jaguar is threatened by loss and fragmentation of habitat, illegal killing in retaliation for livestock depredation and for illegal trade in jaguar body parts. It is listed as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List since 2002, as the jaguar population has probably declined by 20–25% since the mid-1990s. Deforestation is a major threat to the jaguar across its range. Habitat loss was most rapid in drier regions such as the Argentine pampas, the arid grasslands of Mexico and the southwestern United States.[1]

In 2002, it was estimated that the range of the jaguar had declined to about 46% of its range in the early 20th century.[51] In 2018, it was estimated that its range had declined by 55% in the last century. The only remaining stronghold is the Amazon rainforest, a region that is rapidly being fragmented by deforestation.[104] Between 2000 and 2012, forest loss in the jaguar range amounted to 83.759 km2 (32.340 sq mi), with fragmentation increasing in particular in corridors between Jaguar Conservation Units (JCUs).[105] By 2014, direct linkages between two JCUs in Bolivia were lost, and two JCUs in northern Argentina became completely isolated due to deforestation.[106]

In Mexico, the jaguar is primarily threatened by poaching. Its habitat is fragmented in northern Mexico, in the Gulf of Mexico and the Yucatán Peninsula, caused by changes in land use, construction of roads and tourism infrastructure.[107] In Panama, 220 of 230 jaguars were killed in retaliation for predation on livestock between 1998 and 2014.[108] In Venezuela, the jaguar was extirpated in about 26% of its range in the country since 1940, mostly in dry savannas and unproductive scrubland in the northeastern region of Anzoátegui.[109] In Ecuador, the jaguar is threatened by reduced prey availability in areas where the expansion of the road network facilitated access of human hunters to forests.[110] In the Alto Paraná Atlantic forests, at least 117 jaguars were killed in Iguaçu National Park and the adjacent Misiones Province between 1995 and 2008.[111] Some Afro-Colombians in the Colombian Chocó Department hunt jaguars for consumption and sale of meat.[112] Between 2008 and 2012, at least 15 jaguars were killed by livestock farmers in central Belize.[113]

The international trade of jaguar skins boomed between the end of the Second World War and the early 1970s.[114] Significant declines occurred in the 1960s, as more than 15,000 jaguars were yearly killed for their skins in the Brazilian Amazon alone; the trade in jaguar skins decreased since 1973 when the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species was enacted.[115] Interview surveys with 533 people in the northwestern Bolivian Amazon revealed that local people killed jaguars out of fear, in retaliation, and for trade.[116] Between August 2016 and August 2019, jaguar skins and body parts were seen for sale in tourist markets in the Peruvian cities of Lima, Iquitos and Pucallpa.[117] Human-wildlife conflict, opportunistic hunting and hunting for trade in domestic markets are key drivers for killing jaguars in Belize and Guatemala.[118] Seizure reports indicate that at least 857 jaguars were involved in trade between 2012 and 2018, including 482 individuals in Bolivia alone; 31 jaguars were seized in China .[119] Between 2014 and early 2019, 760 jaguar fangs were seized that originated in Bolivia and were destined for China. Undercover investigations revealed that the smuggling of jaguar body parts is run by Chinese residents in Bolivia.[120]

Conservation

The jaguar is listed on CITES Appendix I, which means that all international commercial trade in jaguars or their body parts is prohibited. Hunting jaguars is prohibited in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, French Guiana, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Suriname, the United States, and Venezuela. Hunting jaguars is restricted in Guatemala and Peru.[1] In Ecuador, hunting jaguars is prohibited, and it is classified as threatened with extinction.[121] In Guyana, it is protected as an endangered species, and hunting it is illegal.[122]

In 1986, the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary was established in Belize as the world's first protected area for jaguar conservation.[123]

Jaguar Conservation Units

In 1999, field scientists from 18 jaguar range countries determined the most important areas for long-term jaguar conservation based on the status of jaguar population units, stability of prey base and quality of habitat. These areas, called "Jaguar Conservation Units" (JCUs), are large enough for at least 50 breeding individuals and range in size from 566 to 67,598 km2 (219 to 26,100 sq mi); 51 JCUs were designated in 36 geographic regions including:[51]

- the Sierra Madre Occidental and Sierra de Tamaulipas in Mexico

- the Selva Maya tropical forests extending over Mexico, Belize and Guatemala

- the Chocó–Darién moist forests from Honduras and Panama to Colombia

- Venezuelan Llanos

- northern Cerrado and Amazon basin in Brazil

- Tropical Andes in Bolivia and Peru

- Misiones Province in Argentina

Optimal routes of travel between core jaguar population units were identified across its range in 2010 to implement wildlife corridors that connect JCUs. These corridors represent areas with the shortest distance between jaguar breeding populations, require the least possible energy input of dispersing individuals and pose a low mortality risk. They cover an area of 2,600,000 km2 (1,000,000 sq mi) and range in length from 3 to 1,102 km (1.9 to 684.8 mi) in Mexico and Central America and from 489.14 to 1,607 km (303.94 to 998.54 mi) in South America.[124] Cooperation with local landowners and municipal, state, or federal agencies is essential to maintain connected populations and prevent fragmentation in both JCUs and corridors.[125] Seven of 13 corridors in Mexico are functioning with a width of at least 14.25 km (8.85 mi) and a length of no more than 320 km (200 mi). The other corridors may hamper passage, as they are narrower and longer.[126]

In August 2012, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service set aside 3,392.20 km2 (838,232 acres) in Arizona and New Mexico for the protection of the jaguar.[127] The Jaguar Recovery Plan was published in April 2019, in which Interstate 10 is considered to form the northern boundary of the Jaguar Recovery Unit in Arizona and New Mexico.[128]

In Mexico, a national conservation strategy was developed from 2005 on and published in 2016.[107] The Mexican jaguar population increased from an estimated 4,000 individuals in 2010 to about 4,800 individuals in 2018. This increase is seen as a positive effect of conservation measures that were implemented in cooperation with governmental and non-governmental institutions and landowners.[129]

An evaluation of JCUs from Mexico to Argentina revealed that they overlap with high-quality habitats of about 1,500 mammals to varying degrees. Since co-occurring mammals benefit from the JCU approach, the jaguar has been called an umbrella species.[130] Central American JCUs overlap with the habitat of 187 of 304 regional endemic amphibian and reptile species, of which 19 amphibians occur only in the jaguar range.[131]

Approaches

In setting up protected reserves, efforts generally also have to be focused on the surrounding areas, as jaguars are unlikely to confine themselves to the bounds of a reservation, especially if the population is increasing in size. Human attitudes in the areas surrounding reserves and laws and regulations to prevent poaching are essential to make conservation areas effective.[132]

To estimate population sizes within specific areas and to keep track of individual jaguars, camera trapping and wildlife tracking telemetry are widely used, and feces are sought out with the help of detection dogs to study jaguar health and diet.[85][133]

Current conservation efforts often focus on educating ranch owners and promoting ecotourism.[134] Ecotourism setups are being used to generate public interest in charismatic animals such as the jaguar while at the same time generating revenue that can be used in conservation efforts. A key concern in jaguar ecotourism is the considerable habitat space the species requires. If ecotourism is used to aid in jaguar conservation, some considerations need to be made as to how existing ecosystems will be kept intact, or how new ecosystems will be put into place that are large enough to support a growing jaguar population.[135]

Conservationists and professionals in Mexico and the United States have established the 56,000 acres (23,000 ha) Northern Jaguar Reserve in northern Mexico. Advocacy for reintroduction of the jaguar to its former range in Arizona and New Mexico have been supported by documentation of natural migrations by individual jaguars into the southern reaches of both states, the recency of extirpation from those regions by human action, and supportive arguments pertaining to biodiversity, ecological, human, and practical considerations.[136]

In culture and mythology

In the pre-Columbian Americas, the jaguar was a symbol of power and strength. In the Andes, a jaguar cult disseminated by the early Chavín culture became accepted over most of today's Peru by 900 BC.[137] The later Moche culture in northern Peru used the jaguar as a symbol of power in many of their ceramics.[138] In the Muisca religion in Altiplano Cundiboyacense, the jaguar was considered a sacred animal, and people dressed in jaguar skins during religious rituals.[139] The skins were traded with peoples in the nearby Orinoquía Region.[140] The name of the Muisca ruler Nemequene was derived from the Chibcha words nymy and quyne, meaning "force of the jaguar".[141][142]

Sculptures with "Olmec were-jaguar" motifs were found on the Yucatán Peninsula in Veracruz and Tabasco; they show stylized jaguars with half-human faces.[143] In the later Maya civilization, the jaguar was believed to facilitate communication between the living and the dead and to protect the royal household. The Maya saw these powerful felines as their companions in the spiritual world, and several Maya rulers bore names that incorporated the Mayan word for jaguar b'alam in many of the Mayan languages. Balam remains a common Maya surname, and it is also the name of Chilam Balam, a legendary author to whom are attributed 17th and 18th-centuries Maya miscellanies preserving much important knowledge. Remains of jaguar bones were discovered in a burial site in Guatemala, which indicates that Mayans may have kept jaguars as pets.[144]

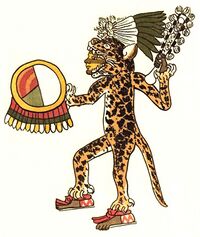

The Aztec civilization shared this image of the jaguar as the representative of the ruler and as a warrior. The Aztecs formed an elite warrior class known as the Jaguar warrior. In Aztec mythology, the jaguar was considered to be the totem animal of the powerful deities Tezcatlipoca[145][146] and Tepeyollotl.[147]

A conch shell gorget depicting a jaguar was found in a burial mound in Benton County, Missouri. The gorget shows evenly-engraved lines and measures 104 mm × 98 mm (4.1 in × 3.9 in).[57] Rock drawings made by the Hopi, Anasazi and Pueblo all over the desert and chaparral regions of the American Southwest show an explicitly spotted cat, presumably a jaguar, as it is drawn much larger than an ocelot.[53]

The jaguar is also used as a symbol in contemporary culture.[148] It is the national animal of Guyana and is featured in its coat of arms.[149] The flag of the Department of Amazonas features a black jaguar silhouette leaping towards a hunter.[150] The crest of the Argentine Rugby Union features a jaguar.[151]

See also

- List of largest cats

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Quigley, H.; Foster, R.; Petracca, L.; Payan, E.; Salom, R.; Harmsen, B. (2017). "Panthera onca". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T15953A123791436. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T15953A50658693.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/15953/123791436. Retrieved 15 January 2022.{{cite iucn}}: error: |doi= / |page= mismatch (help)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Species Panthera onca". in Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 546–547. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=14000240.

- ↑ Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1975). "Jaguar Panthera onca (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild Cats of the World. New York: Taplinger Publishing. pp. 247–265. ISBN 978-0-8008-8324-9.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Seymour, K. L. (1989). "Panthera onca". Mammalian Species (340): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3504096. http://www.science.smith.edu/departments/Biology/VHAYSSEN/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-340-01-0001.pdf.

- ↑ Qualls, E. J. (2012). "The dialects of English". The Qualls Concise English Grammar. Danaan Press. ISBN 9781890000097. https://books.google.com/books?id=tjrd5UnFT2gC&pg=PT29.

- ↑ "Jaguar". https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/pronunciation/english/jaguar.

- ↑ Labat, J.B. (1731). "Once, espèce de Tigre". Voyage du chevalier Des Marchais en Guinée, isles voisines, et à Cayenne, fait en 1725, 1726 & 1727. III. Amsterdam: La Compagnie. p. 285. https://books.google.com/books?id=dfdWAAAAcAAJ&pg=RA6-PA5. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ↑ Ray, J. (1693). "Pardus an Lynx brasiliensis, Jaguara". Synopsis Methodica Animalium Quadrupedum et Serpentini Generis. Vulgarium Notas Characteristicas, Rariorum Descriptiones integras exhibens. London: S. Smith & B. Walford. p. 168. https://archive.org/details/synopsismethodic00rayj/page/168/mode/1up.

- ↑ Liddell, H. G.; Scott, R. (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon (Revised and augmented ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0057%3Aentry%3D%2377441. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Felis onca" (in la). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. I (Decima, reformata ed.). Holmiae: Laurentius Salvius. p. 42. https://archive.org/stream/mobot31753000798865#page/41/mode/2up.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Pocock, R. I. (1939). "The races of jaguar (Panthera onca)". Novitates Zoologicae 41: 406–422. https://archive.org/details/cbarchive_123320_theracesofjaguarpantheraonca9999.

- ↑ Blainville, H. M. D. de (1843). "F. leo nubicus" (in fr). Ostéographie ou description iconographique comparée du squelette et du système dentaire des mammifères récents et fossils pour servir de base à la zoologie et la géologie. II. Paris: J. B. Baillière et Fils. p. Plate VIII. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6538959f/f171.item. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ↑ Gray, J. E. (1857). "Notice of a new species of jaguar from Mazatlan, living in the gardens of the Zoological Society". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 25: 278. https://archive.org/details/lietuvostsrmoksl56liet/page/278/mode/2up.

- ↑ Ameghino, F. (1888). "Formación Pampeana" (in es). Los Mamíferos fósiles de la República Argentina. Buenos Aires: Pablo E. Coni é hijos. pp. 473–493. https://archive.org/details/mamferosfsil00ameg/page/476/mode/1up.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Mearns, E. A. (1901). "The American Jaguars". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 14: 137–143. https://archive.org/details/3908800952802714biolrich/page/138/mode/2up.

- ↑ Hollister, N. (1915). "Two new South American jaguars". Proceedings of the United States National Museum 48 (2069): 169–170. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.48-2069.169. https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofuni481915unit/page/168/mode/2up.

- ↑ Goldman, E. A. (1932). "The jaguars of North America". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 45: 143–146. https://archive.org/details/proceedingsofbi451932biol/page/142/mode/2up.

- ↑ Nelson, E. W.; Goldman, E. A. (1933). "Revision of the jaguars". Journal of Mammalogy 14 (3): 221–240. doi:10.2307/1373821.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Eizirik, E.; Kim, J. H.; Menotti-Raymond, M.; Crawshaw P. G. Jr.; O'Brien, S. J.; Johnson, W. E. (2001). "Phylogeography, population history and conservation genetics of jaguars (Panthera onca, Mammalia, Felidae)". Molecular Ecology 10 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01144.x. PMID 11251788. Bibcode: 2001MolEc..10...65E. https://zenodo.org/record/1236534.

- ↑ Larson, S. E. (1997). "Taxonomic re-evaluation of the jaguar". Zoo Biology 16 (2): 107–120. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2361(1997)16:2<107::AID-ZOO2>3.0.CO;2-E.

- ↑ Ruiz-Garcia, M.; Payan, E.; Murillo, A.; Alvarez, D. (2006). "DNA microsatellite characterization of the jaguar (Panthera onca) in Colombia". Genes & Genetic Systems 81 (2): 115–127. doi:10.1266/ggs.81.115. PMID 16755135. https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/ggs/81/2/81_2_115/_pdf. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ↑ Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V. et al. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group". Cat News Special Issue 11: 70–71. https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/32616/A_revised_Felidae_Taxonomy_CatNews.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y#page=70. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Johnson, W. E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W. J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E.; O'Brien, S. J. (2006). "The late miocene radiation of modern Felidae: A genetic assessment". Science 311 (5757): 73–77. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146. Bibcode: 2006Sci...311...73J. https://zenodo.org/record/1230866. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Werdelin, L.; Yamaguchi, N.; Johnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae)". in Macdonald, D. W.; Loveridge, A. J.. Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 59–82. ISBN 978-0-19-923445-5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266755142. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ↑ Li, G.; Davis, B. W.; Eizirik, E.; Murphy, W. J. (2016). "Phylogenomic evidence for ancient hybridization in the genomes of living cats (Felidae)". Genome Research 26 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1101/gr.186668.114. PMID 26518481.

- ↑ Davis, B. W.; Li, G.; Murphy, W. J. (2010). "Supermatrix and species tree methods resolve phylogenetic relationships within the big cats, Panthera (Carnivora: Felidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 56 (1): 64–76. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.036. PMID 20138224. https://www.academia.edu/12157986.

- ↑ Mazák, J. H.; Christiansen, P.; Kitchener, A. C.; Goswami, A. (2011). "Oldest known pantherine skull and evolution of the tiger". PLOS ONE 6 (10): e25483. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025483. PMID 22016768. Bibcode: 2011PLoSO...625483M.

- ↑ Argant, A.; Argant, J. (2011). "The Panthera gombaszogensis story: the contribution of the Château Breccia (Saône-et-Loire, Burgundy, France)". Quaternaire (Hors-serie 4): 247–269. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286036249. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ↑ Jiangzuo, Q.; Liu, J. (2020). "First record of the Eurasian jaguar in southern Asia and a review of dental differences between pantherine cats". Journal of Quaternary Science 35 (6): 817–830. doi:10.1002/jqs.3222. Bibcode: 2020JQS....35..817J.

- ↑ Chahud, A.; Okumura, M. (2020). "The presence of Panthera onca Linnaeus 1758 (Felidae) in the Pleistocene of the region of Lagoa Santa, State of Minas Gerais, Brazil". Historical Biology 33 (10): 2496–2503. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1808975.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Hayward, M. W.; Kamler, J. F.; Montgomery, R. A.; Newlove, A. (2016). "Prey Preferences of the Jaguar Panthera onca Reflect the Post-Pleistocene Demise of Large Prey". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 3: 148. doi:10.3389/fevo.2015.00148.

- ↑ Hope, M. K.; Deem, S. L. (2006). "Retrospective Study of Morbidity and Mortality of Captive Jaguars (Panthera onca) in North America: 1982–2002". Zoo Biology 25 (6): 501–512. doi:10.1002/zoo.20112. https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/11687/Zoo%20Biology%2C%20Vol.%2025%2C%20Issue%206%20Retrospective%20Study%20of%20Morbidity%20and%20Mortality%20of%20Captive%20Jaguars....pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ↑ Rich, M.S. (1976). "The jaguar". Zoonoz 49 (9): 14–17.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Scognamillo, D.; Maxit, I. E.; Sunquist, M.; Polisar, J. (2003). "Coexistence of jaguar (Panthera onca) and puma (Puma concolor) in a mosaic landscape in the Venezuelan llanos". Journal of Zoology 259 (3): 269–279. doi:10.1017/S0952836902003230.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Nowak, R.M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. 2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 831. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=T37sFCl43E8C&pg=PAPA831.

- ↑ Burnie, D.; Wilson, D.E. (2001). Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. New York City: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Gonyea, W.J. (1976). "Adaptive differences in the body proportions of large felids". Acta Anatomica 96 (1): 81–96. doi:10.1159/000144663. PMID 973541.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 Nuanaez, R.; Miller, B.; Lindzey, F. (2000). "Food habits of jaguars and pumas in Jalisco, Mexico". Journal of Zoology 252 (3): 373–379. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb00632.x. http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=58851. Retrieved 8 September 2006.

- ↑ Allen, W.L.; Cuthill, I.C.; Scott-Samuel, N.E.; Baddeley, R. (2010). "Why the leopard got its spots: relating pattern development to ecology in felids". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 278 (1710): 1373–1380. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1734. PMID 20961899.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "Jaguar, Panthera onca (Linnaeus, 1758)". Wild Cats. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. pp. 118–122. http://carnivoractionplans1.free.fr/wildcats.pdf#page=143. Retrieved 31 August 2006.

- ↑ Wroe, S.; McHenry, C.; Thomason, J. (2006). "Bite club: comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behavior in fossil taxa". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 272 (1563): 619–625. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2986. PMID 15817436.

- ↑ Christiansen, P. (2007). "Canine morphology in the larger Felidae: implications for feeding ecology". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 91 (4): 573–592. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00819.x.

- ↑ Hartstone-Rose, A.; Perry, J.M.G.; Morrow, C.J. (2012). "Bite Force Estimation and the Fiber Architecture of Felid Masticatory Muscles". The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology 295 (8): 1336–1351. doi:10.1002/ar.22518. PMID 22707481.

- ↑ Brown, D.E.; Lopez-Gonzalez, C.A. (2001). Borderland jaguars: tigres de la frontera. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

- ↑ Eizirik, E.; Yuhki, N.; Johnson, W.E.; Menotti-Raymond, M.; Hannah, S.S.; O'Brien, S.J. (2003). "Molecular Genetics and Evolution of Melanism in the Cat Family". Current Biology 13 (5): 448–453. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00128-3. PMID 12620197.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Mooring, M. S.; Eppert, A. A.; Botts, R. T. (2020). "Natural Selection of Melanism in Costa Rican Jaguar and Oncilla: A Test of Gloger's Rule and the Temporal Segregation Hypothesis". Tropical Conservation Science 13: 1–15. doi:10.1177/1940082920910364.

- ↑ Dinets, V.; Polechla, P.J. (2005). "First documentation of melanism in the jaguar (Panthera onca) from northern Mexico". Cat News 42: 18. http://dinets.travel.ru/blackjaguar.htm.

- ↑ Núñez, M.C.; Jiménez, E.C. (2009). "A new record of a black jaguar, Panthera onca (Carnivora: Felidae) in Costa Rica". Brenesia 71: 67–68. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313473228. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ↑ Sáenz-Bolaños, C.; Montalvo, V.; Fuller, T.K.; Carrillo, E. (2015). "Records of black jaguars at Parque Nacional Barbilla, Costa Rica". Cat News (62): 38–39.

- ↑ Yacelga, M.; Craighead, K. (2019). "Melanistic jaguars in Panama". Cat News (70): 39–41. https://www.academia.edu/41977728. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Sanderson, E. W.; Redford, K. H.; Chetkiewicz, C. L. B.; Medellin, R. A.; Rabinowitz, A. R.; Robinson, J. G.; Taber, A. B. (2002). "Planning to save a species: the jaguar as a model". Conservation Biology 16 (1): 58–72. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00352.x. PMID 35701976. Bibcode: 2002ConBi..16...58S.

- ↑ Brown, D. E.; González, C. A. L. (2000). "Notes on the occurrences of jaguars in Arizona and New Mexico". The Southwestern Naturalist 45 (4): 537–542. doi:10.2307/3672607.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Pavlik, S. (2003). "Rohonas and spotted Lions: The historical and cultural occurrence of the Jaguar, Panthera onca, among the native tribes of the American Southwest". Wíčazo Ša Review 18 (1): 157–175. doi:10.1353/wic.2003.0006.

- ↑ Culver, M. (2016). Open-File Report (Report). 2016-1095. Reston, VA: U.S. Geological Survey. doi:10.3133/ofr20161095.

- ↑ Colchero, F.; Conde, D. A.; Manterola, C.; Chávez, C.; Rivera, A.; Ceballos, G. (2011). "Jaguars on the move: modeling movement to mitigate fragmentation from road expansion in the Mayan Forest". Animal Conservation 14 (2): 1–9. doi:10.1111/J.1469-1795.2010.00406.X. Bibcode: 2011AnCon..14..158C. https://www.demogr.mpg.de/publications/files/4097_1300970681_1_ArticlePdf.pdf. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ Caso, A.; Domínguez, E. F. (2018). "Confirmed presence of jaguar, ocelot and jaguarundi in the Sierra of San Carlos, Mexico". Cat News (68): 31–32.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Daggett, P. M.; Henning, D. R. (1974). "The Jaguar in North America". American Antiquity 39 (3): 465–469. doi:10.2307/279437.

- ↑ Merriam, C.H. (1919). "Is the Jaguar entitled to a place in the Californian fauna?". Journal of Mammalogy 1 (1): 38–42. doi:10.1093/jmammal/1.1.38. https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article-abstract/1/1/38/875846?redirectedFrom=fulltext. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ↑ Schmidly, D. J.; Bradley, R. D. (2016). The Mammals of Texas (Seventh ed.). Lubbock: University of Texas Press. doi:10.7560/308868. ISBN 9781477310021. https://www.depts.ttu.edu/nsrl/mammals-of-texas-online-edition/Accounts_Extinct_Carnivora/Panthera_onca.php.

- ↑ Rizzo, W. (2005). "Return of the Jaguar?". Smithsonian Magazine. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/ist/?next=/science-nature/return-of-the-jaguar-110630052/. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- ↑ Harmsen, B. J.; Foster, R. J.; Silver, S. C.; Ostro, L. E. T.; Doncaster, C. P. (2009). "Spatial and temporal interactions of sympatric jaguars (Panthera onca) and pumas (Puma concolor) in a neotropical forest". Journal of Mammalogy 90 (3): 612–620. doi:10.1644/08-MAMM-A-140R.1.

- ↑ Foster, V.C.; Sarmento, P.; Sollmann, R.; Tôrres, N.; Jácomo, A. T.; Negrões, N.; Fonseca, C.; Silveira, L. (2013). "Jaguar and Puma Activity Patterns and Predator-Prey Interactions in Four Brazilian Biomes". Biotropica 45 (3): 373–379. doi:10.1111/btp.12021. Bibcode: 2013Biotr..45..373F. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234153943. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ↑ Astete, S.R.; Sollmann, R.; Silveira, L. (2008). "Comparative ecology of jaguars in Brazil". Cat News (Special Issue 4): 9–14.

- ↑ Harmsen, B.J.; Foster, R.J.; Silver, S. C.; Ostro, L.E.T.; Doncaster, C.P. (2011). "Jaguar and puma activity patterns in relation to their main prey". Mammalian Biology – Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 76 (3): 320–324. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2010.08.007.

- ↑ Nijhawan, S. (2012). "Conservation units, priority areas and dispersal corridors for jaguars in Brazil". Cat News (Special Issue): 43–47. http://www.catsg.org/fileadmin/filesharing/5.Cat_News/5.3._Special_Issues/5.3.7._SI_7/Nijhawan_2012_Conservation_units_and_corrdors_for_jaguars_in_Brazil.pdf. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ↑ Petracca, L.S.; Ramírez-Bravo, O.E.; Hernández-Santín, L. (2014). "Occupancy estimation of jaguar Panthera onca to assess the value of east-central Mexico as a jaguar corridor". Oryx 48 (1): 133–140. doi:10.1017/S0030605313000069.

- ↑ Wright, S. J.; Gompper, M. E.; DeLeon, B. (1994). "Are large predators keystone species in Neotropical forests? The evidence from Barro Colorado Island". Oikos 71 (2): 279–294. doi:10.2307/3546277. Bibcode: 1994Oikos..71..279W. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270356084. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ↑ Gutiérrez-González, C. E.; López-González, C. A. (2017). "Jaguar interactions with pumas and prey at the northern edge of jaguars' range". PeerJ 5 (5): e2886. doi:10.7717/peerj.2886. PMID 28133569.

- ↑ Iriarte, J. A.; Franklin, W.L.; Johnson, W.E.; Redford, K.H. (1990). "Biogeographic variation of food habits and body size of the America puma". Oecologia 85 (2): 185–190. doi:10.1007/BF00319400. PMID 28312554. Bibcode: 1990Oecol..85..185I.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Miranda, E.; Menezes, J.; Rheingantz, M. L. (2016). "Reptiles as principal prey? Adaptations for durophagy and prey selection by jaguar (Panthera onca)". Journal of Natural History 50 (31–32): 2021–2035. doi:10.1080/00222933.2016.1180717. Bibcode: 2016JNatH..50.2021M. https://zenodo.org/record/3993366. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Eriksson, C.; Kantek, D.L.; Miyazaki, S.S.; Morato, R.G.; dos Santos-Filho, M.; Ruprecht, J.S.; Peres, C.A.; Levi, T. (2022). "Extensive aquatic subsidies lead to territorial breakdown and high density of an apex predator". Ecology 103 (1): e03543. doi:10.1002/ecy.3543. PMID 34841521. Bibcode: 2022Ecol..103E3543E.

- ↑ Amit, R.; Gordillo-Chávez, E.J.; Bone, R. (2013). "Jaguar and puma attacks on livestock in Costa Rica". Human-Wildlife Interactions 7 (1): 77–84.

- ↑ Zarco-González, M.M.; Monroy-Vilchis, O.; Alaníz, J. (2013). "Spatial model of livestock predation by jaguar and puma in Mexico: conservation planning". Biological Conservation 159: 80–87. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.11.007. Bibcode: 2013BCons.159...80Z.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 Emmons, L. H. (1987). "Comparative feeding ecology of fields in a neotropical rain forest". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 20 (4): 271–283. doi:10.1007/BF00292180. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225982805. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ↑ Emmons, L. H. (1989). "Jaguar predation on chelonians". Journal of Herpetology 23 (3): 311–314. doi:10.2307/1564460.

- ↑ Rosa, C. L. de la; Nocke, C. C. (2000). "Jaguar (Panthera onca)". A guide to the carnivores of Central America: natural history, ecology, and conservation. University of Texas Press. pp. 39–?. ISBN 978-0-292-71604-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=x5ihAwAAQBAJ&pg=PT39. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ↑ Schaller, G.B.; Vasconselos, J.M.C. (1978). "Jaguar predation on capybara". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 43: 296–301. https://www.zobodat.at/pdf/Zeitschrift-Saeugetierkunde_43_0296-0301.pdf. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ↑ Cavalcanti, S. M. C.; Gese, E. M. (2010). "Kill rates and predation patterns of jaguars (Panthera onca) in the southern Pantanal, Brazil". Journal of Mammalogy 91 (3): 722–736. doi:10.1644/09-MAMM-A-171.1.

- ↑ Baker, W. K. Jr.. "Guidelines for Captive Management of Jaguars". in Law, C.. Jaguar Species Survival Plan. Association of Zoos and Aquariums. pp. 8–16. http://www.jaguarssp.com/Animal%20Mgmt/JAGUAR%20GUIDELINES.pdf.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Schaller, G. B.; Crawshaw, P. G. Jr. (1980). "Movement patterns of Jaguar". Biotropica 12 (3): 161–168. doi:10.2307/2387967. Bibcode: 1980Biotr..12..161S.

- ↑ Jędrzejewski, W.; Hoogesteijn, R.; Devlin, A. L. (2022). "Collaborative behaviour and coalitions in male jaguars (Panthera onca)—evidence and comparison with other felids". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 76 (9): 121. doi:10.1007/s00265-022-03232-3.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Rabinowitz, A. R.; Nottingham, B.G. Jr. (1986). "Ecology and behaviour of the Jaguar (Panthera onca) in Belize, Central America". Journal of Zoology 210 (1): 149–159. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1986.tb03627.x.

- ↑ Harmsen, B. J.; Foster, R.J.; Gutierrez, S.M.; Marin, S.Y.; Doncaster, C.P. (2007). "Scrape-marking behavior of jaguars (Panthera onca) and pumas (Puma concolor)". Journal of Mammalogy 91 (5): 1225–1234. doi:10.1644/09-mamm-a-416.1.

- ↑ Morato, R.G.; Stabach, J.A.; Fleming, C.H.; Calabrese, J.M.; De Paula, R.C.; Ferraz, K.M.; Kantek, D.L.; Miyazaki, S.S. et al. (2016). "Space use and movement of a neotropical top predator: the endangered Jaguar". PLOS ONE 11 (12): e0168176. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0168176. PMID 28030568. Bibcode: 2016PLoSO..1168176M.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Soisalo, M.K.; Cavalcanti, S.M.C. (2006). "Estimating the density of a Jaguar population in the Brazilian Pantanal using camera-traps and capture-recapture sampling in combination with GPS radio-telemetry". Biological Conservation 129 (4): 487–496. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.11.023. Bibcode: 2006BCons.129..487S. http://www.ekonoiz.com/Eco_Projects/Jaguar_Conservation/estimatingthedensityofjaguarsinthepantanal.pdf.

- ↑ Peters, G.; Tonin-Leyhausen, B. (1999). "Evolution of Acoustic Communication Signals of Mammals: Friendly Close-Range Vocalizations in Felidae (Carnivora)". Journal of Mammalian Evolution 6 (2): 129–159. doi:10.1023/A:1020620121416.

- ↑ Leuchtenberger, C.; Crawshaw, P. G.; Mourão, G.; Lehn, C. R. (2009). "Courtship behavior by Jaguars in the Pantanal of Mato Grosso do Sul". Natureza & Conservaç~ao Revista Brasileira de Conservaç~ao da Natureza 7 (1): 218–222. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263424625. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ Wildt, D.E.; Platz, C.C.; Chakraborty, P.K.; Seager, S.W.J. (1979). "Oestrous and ovarian activity in a female jaguar (Panthera onca)". Reproduction 56 (2): 555–558. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0560555. PMID 383976.

- ↑ Barnes, S.A.; Teare, J.A.; Staaden, S.; Metrione, L.; Penfold, L.M. (2016). "Characterization and manipulation of reproductive cycles in the jaguar (Panthera onca)". General and Comparative Endocrinology 225: 95–103. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2015.09.012. PMID 26399935.

- ↑ Jorge-Neto, P. N.; Luczinski, T. C.; Ribeiro de Araújo, G.; Salomão, J.; de Souza Traldi, A.; Melo dos Santos, J. A.; Requena, L. A.; Machado Gianni, M. C. et al. (2020). "Can jaguar (Panthera onca) ovulate without copulation?". Theriogenology 147: 57–61. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2020.02.026. PMID 32092606.

- ↑ Hemmer, H. (1976). "Gestation period and postnatal development in felids". in Eaton, R.L.. The world's cats. 3. Contributions to Biology, Ecology, Behavior and Evolution. Seattle: Carnivore Research Institute, Univ. Washington. pp. 143–165.

- ↑ Mondolfi, E.; Hoogesteijn, R. (1986). "Notes on the biology and status of the jaguar (Panthera onca) in Venezuela". Cats of the world: biology, conservation and management. Washington, DC: National Wildlife Federation. pp. 85–123. ISBN 978-091218679-5.

- ↑ Morato, R. G.; Guimaraes, M.A.B.; Ferriera, F.; Verreschi, I.T.d.N.; Barnabe, R.C. (1999). "Reproductive characteristics of captive male jaguars". Brazilian Journal of Veterinary Research and Animal Science 36 (5). doi:10.1590/S1413-95961999000500008.

- ↑ Pacifici, M.; Santini, L.; Di Marco, M.; Baisero, D.; Francucci, L.; Grottolo Marasini, G.; Visconti, P.; Rondinini, C. (2013). "Generation length for mammals". Nature Conservation 5 (5): 87–94. doi:10.3897/natureconservation.5.5734.

- ↑ Cavalcanti, S. M. C.; Gese, E. M. (2009). "Spatial ecology and social interactions of jaguars (Panthera onca) in the southern Pantanal, Brazil". Journal of Mammalogy 90 (4): 935–945. doi:10.1644/08-MAMM-A-188.1.

- ↑ Egerton, J. (2006). "Jaguars: Magnificence in the Southwest". Wild Tracks. http://www.southwestwildlife.org/pdf/Newsletter/Spring06.pdf. Retrieved 6 December 2009.

- ↑ Soares, T. N.; Telles, M. P.; Resende, L.V.; Silveira, L. et al. (2006). "Paternity testing and behavioral ecology: A case study of jaguars (Panthera onca) in Emas National Park, Central Brazil". Genetics and Molecular Biology 29 (4): 735–740. doi:10.1590/S1415-47572006000400025.

- ↑ Tortato, F.R.; Devlin, A.L.; Hoogesteijn, R.; Júnior, J.A.M.; Frair, J.L.; Crawshaw, P.G.; Izzo, T.J.; Quigley, H.B. (2017). "Infanticide in a jaguar (Panthera onca) population – does the provision of livestock carcasses increase the risk?". Acta Ethologica 20 (1): 69–73. doi:10.1007/s10211-016-0241-4. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308940647. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ↑ Stasiukynas, D. C.; Boron, V.; Hoogesteijn, R.; Barragán2, J.; Martin, A.; Tortato, F.; Rincón, S.; Payán, E. (2021). "Hide and flirt: observed behavior of female jaguars (Panthera onca) to protect their young cubs from adult males". Acta Ethologica 25 (3): 179–183. doi:10.1007/s10211-021-00384-9.

- ↑ Porter, J. H. (1894). "The Jaguar". Wild beasts; a study of the characters and habits of the elephant, lion, leopard, panther, jaguar, tiger, puma, wolf, and grizzly bear. New York: C. Scribner's sons. pp. 174–195. https://archive.org/stream/wildbeastsstud00port#page/n197/mode/2up.

- ↑ De Paula, R.; Campos Neto, M. F.; Morato, R. G. (2008). "First official record of Human killed by Jaguar in Brazil". Cat News (49): 31–32.

- ↑ Iserson, K. V.; Francis, A. M. (2015). "Jaguar attack on a child: Case report and literature review". Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 16 (2): 303–309. doi:10.5811/westjem.2015.1.24043. PMID 25834674.

- ↑ Seidensticker, J.; Lumpkin, S. (2016). Cats in Question: The Smithsonian Answer Book. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-158834546-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=09LwCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT303.

- ↑ De La Torre, J.A.; González-Maya, J.F.; Zarza, H.; Ceballos, G.; Medellín, R.A. (2018). "The jaguar's spots are darker than they appear: assessing the global conservation status of the jaguar Panthera onca". Oryx 52 (2): 300–315. doi:10.1017/S0030605316001046.

- ↑ Olsoy, P.J.; Zeller, K.A.; Hicke, J.A.; Quigley, H.B.; Rabinowitz, A.R.; Thornton, D.H. (2016). "Quantifying the effects of deforestation and fragmentation on a range-wide conservation plan for jaguars". Biological Conservation 203: 8–16. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.08.037. Bibcode: 2016BCons.203....8O. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307954092. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ↑ Thompson, J.J.; Velilla, M. (2017). "Modeling the effects of deforestation on the connectivity of jaguar Panthera onca populations at the southern extent of the species' range". Endangered Species Research 34: 109–121. doi:10.3354/esr00840. https://www.int-res.com/articles/esr2017/34/n034p109.pdf. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Ceballos, G.; Zarza, H.; Chávez, C.; González-Maya, J.F. (2016). "Ecology and Conservation of Jaguars in Mexico". Tropical conservation: Perspectives on local and global priorities. Oxford University Press. pp. 273–289. ISBN 978-019976698-7. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307985045. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ↑ Moreno, R.; Meyer, N.; Olmos, M.; Hoogesteijn, R.; Hoogesteijn, A.L. (2015). "Causes of jaguar killing in Panama – a long term survey using interviews". Cat News (62): 40–42. https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/29640/CN62_Moreno_et_al_2015.pdf. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ↑ Jędrzejewski, W.; Boede, E.O.; Abarca, M.; Sánchez-Mercado, A.; Ferrer-Paris, J.R.; Lampo, M.; Velásquez, G.; Carreño, R. et al. (2017). "Predicting carnivore distribution and extirpation rate based on human impacts and productivity factors; assessment of the state of jaguar (Panthera onca) in Venezuela". Biological Conservation 206: 132–142. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.09.027. Bibcode: 2017BCons.206..132J. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312059394. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ↑ Espinosa, S.; Celis, G.; Branch, L.C. (2018). "When roads appear jaguars decline: Increased access to an Amazonian wilderness area reduces potential for jaguar conservation". PLOS ONE 13 (1): e0189740. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189740. PMID 29298311. Bibcode: 2018PLoSO..1389740E.

- ↑ Paviolo, A.; De Angelo, C.D.; Di Blanco, Y.E.; Di Bitetti, M.S. (2008). "Jaguar Panthera onca population decline in the Upper Paraná Atlantic Forest of Argentina and Brazil". Oryx 42 (4): 554–561. doi:10.1017/S0030605308000641.

- ↑ Balaguera-Reina, S.; Gonzalez-Maya, J.F. (2008). "Occasional jaguar hunting for subsistence in Colombian Chocó". Cat News (48): 5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233399315. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ↑ Foster, R.J.; Harmsen, B.J.; Urbina, Y. L.; Wooldridge, R.L.; Doncaster, C.P.; Quigley, H.; Figueroa, O.A. (2020). "Jaguar (Panthera onca) density and tenure in a critical biological corridor". Journal of Mammalogy 101 (6): 1622–1637. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyaa134. PMID 33505226.

- ↑ Broad, S. (1987). The harvest of and trade in Latin American spotted cats (Felidae) and otters (Lutrinae). Cambridge: IUCN Conservation Monitoring Centre. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/119261. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ↑ Weber, W.; Rabinowitz, A. (1996). "A global perspective on large carnivore conservation". Conservation Biology 10 (4): 1046–1054. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10041046.x. Bibcode: 1996ConBi..10.1046W. http://www.jaguarnetwork.org/pdf/71.pdf.

- ↑ Knox, J.; Negrões, N.; Marchini, S.; Barboza, K.; Guanacoma, G.; Balhau, P.; Tobler, M.W.; Glikman, J.A. (2019). "Jaguar persecution without "cowflict": insights from protected territories in the Bolivian Amazon". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 7: 494. doi:10.3389/fevo.2019.00494.

- ↑ Braczkowski, A.; Ruzo, A.; Sanchez, F.; Castagnino, R.; Brown, C.; Guynup, S.; Winter, S.; Gandy, D. et al. (2019). "The ayahuasca tourism boom: An undervalued demand driver for jaguar body parts?". Conservation Science and Practice 1 (12): e126. doi:10.1111/csp2.126. Bibcode: 2019ConSP...1E.126B. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336450042. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ↑ Arias, M.; Hinsley, A.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. (2020). "Characteristics of, and uncertainties about, illegal jaguar trade in Belize and Guatemala". Biological Conservation 250: 108765. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108765. Bibcode: 2020BCons.25008765A. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344172628. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ↑ Morcatty, T.Q.; Bausch Macedo, J.C.; Nekaris, K.A.I.; Ni, Q.; Durigan, C.C.; Svensson, M.S.; Nijman, V. (2020). "Illegal trade in wild cats and its link to Chinese-led development in Central and South America". Conservation Biology 34 (6): 1525–1535. doi:10.1111/cobi.13498. PMID 32484587. Bibcode: 2020ConBi..34.1525M.

- ↑ Earth League International (2020). Unveiling the criminal networks behind jaguar trafficking in Bolivia (Report). Amsterdam: IUCN National Committee of the Netherlands. https://www.iucn.nl/app/uploads/2021/03/iucn_nl_report_jaguar_trafficking_bolivia_media-1.pdf. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ↑ Zapata Ríos, G.; Araguillin, E.; Cevallos, J.; Moreno, F.; Ortega, A.; Rengel, J.; Valarezo, N. (2014) (in es). Plan de Acción para la Conservación del Jaguar en el Ecuador. Quito: Ministerio del Ambiente y Wildlife Conservation Society Ecuador. http://www.wild4ever.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Ecuador-National-Jaguar-Plan.pdf. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ↑ Kerman, I. (2010). Felix, M.-L.. ed. Exploitation of the jaguar, Panthera onca and other large forest cats in Suriname. Paramaribo: WWF Guianas. https://www.a2000greetings.com/downloads/exploitation_of_the_jaguar_and_other_large_forest_cats_in_suriname_irvin_kerman.pdf.

- ↑ Weckel, M.; Giuliano, W.; Silver, S. (2006). "Cockscomb revisited: jaguar diet in the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary, Belize". Biotropica 38 (5): 687–690. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2006.00190.x. Bibcode: 2006Biotr..38..687W.

- ↑ Rabinowitz, A.; Zeller, K.A. (2010). "A range-wide model of landscape connectivity and conservation for the jaguar, Panthera onca". Biological Conservation 143 (4): 939–945. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2010.01.002. Bibcode: 2010BCons.143..939R. https://www.panthera.org/cms/sites/default/files/documents/Rabinowitz_Zeller_2010_Arangewidemodeloflandscapeconnectivityandconservationforjaguar_BioCon.pdf. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ Zeller, K.A.; Rabinowitz, A.; Salom-Perez, R.; Quigley, H. (2013). "The Jaguar Corridor Initiative: A range-wide conservation strategy". Molecular population genetics, evolutionary biology and biological conservation of Neotropical carnivores. New York: Nova Science Publishers. pp. 629–657. ISBN 978-1-62417-071-3. https://conservationcorridor.org/cpb/Zeller_et_al_2013.pdf. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ Rodríguez-Soto, C.; Monroy-Vilchis, O.; Zarco-González, M.M. (2013). "Corridors for jaguar (Panthera onca) in Mexico: Conservation strategies". Journal for Nature Conservation 21 (6): 438–443. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2013.07.002. Bibcode: 2013JNatC..21..438R. https://www.academia.edu/35225702. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ↑ Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service (2012). "Designation of Critical Habitat for Jaguar; Proposed Rule". Federal Register 77 (161): 50214–50242. https://www.fws.gov/southwest/es/arizona/Documents/SpeciesDocs/Jaguar/Jaguar_pCH_FR_8-20-2012.pdf. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ↑ Sanderson, E.W.; Fisher, K.; Peters, R.; Beckmann, J.P.; Bird, B.; Bradley, C.M.; Bravo, J.C.; Grigione, M.M. et al. (2021). "A systematic review of potential habitat suitability for the jaguar Panthera onca in central Arizona and New Mexico, USA". Oryx 56: 116–127. doi:10.1017/S0030605320000459.

- ↑ Ceballos, G.; Zarza, H.; González-Maya, J.F.; de la Torre, J.A.; Arias-Alzate, A.; Alcerreca, C.; Barcenas, H.V.; Carreón-Arroyo, G. et al. (2021). "Beyond words: From jaguar population trends to conservation and public policy in Mexico". PLOS ONE 16 (10): e0255555. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0255555. PMID 34613994. Bibcode: 2021PLoSO..1655555C.

- ↑ Thornton, D.; Zeller, K.; Rondinini, C.; Boitani, L.; Crooks, K.; Burdett, C.; Rabinowitz, A.; Quigley, H. (2016). "Assessing the umbrella value of a range-wide conservation network for jaguars (Panthera onca)". Ecological Applications 26 (4): 1112–1124. doi:10.1890/15-0602. PMID 27509752. Bibcode: 2016EcoAp..26.1112T. https://iris.uniroma1.it/retrieve/handle/11573/893793/279408/Thornton_Assessing_2016.pdf. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ Figel, J.J.; Castañeda, F.; Calderón, A.P.; Torre, J.; García-Padilla, E.; Noss, R.F. (2018). "Threatened amphibians sheltered under the big cat's umbrella: conservation of jaguars Panthera onca (Carnivora: Felidae) and endemic herpetofauna in Central America". Revista de Biología Tropical 66 (4): 1741–1753. doi:10.15517/rbt.v66i4.32544.

- ↑ Gutierrez-Gonzalez, C.E.; Gomez-Ramirez, M.A.; Lopez-Gonzalez, C.A.; Doherty, P.F. (2015). "Are Private Reserves Effective for Jaguar Conservation?". PLOS ONE 10 (9): e0137541. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0137541. PMID 26398115. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1037541G.

- ↑ Furtado, M.M.; Carrillo-Percastegui, S.E.; Jácomo, A.T.A.; Powell, G.; Silveira, L.; Vynne, C.; Sollmann, R. (2008). "Studying jaguars in the wild: past experiences and future perspectives". Cat News (Special Issue 4): 41–47. http://www.catsg.org/fileadmin/filesharing/5.Cat_News/5.3._Special_Issues/5.3.4._SI_4/Furtado_et_al_2008_Jaguar_field_methods_s.pdf. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ↑ Estévez, E. (2009). "Jaguar Refuge in the Llanos Ecoregion". World Wildlife Fund. http://wwf.panda.org/es/nuestro_trabajo/latinoamerica/venezuela/index.cfm?uProjectID=VE0854.

- ↑ Mossaz, A.; Buckley, R.C.; Castley, J.G. (2015). "Ecotourism contributions to conservation of African big cats". Journal for Nature Conservation 28: 112–118. doi:10.1016/j.jnc.2015.09.009. Bibcode: 2015JNatC..28..112M.

- ↑ Sanderson, E. W.; Beckmann, J. P.; Beier, P.; Bird, B.; Bravo, J. C.; Fisher, K.; Grigione, M. M.; Lopez Gonzalez, C. A. et al. (2021). "The case for reintroduction: The jaguar (Panthera onca) in the United States as a model". Conservation Science and Practice 3 (6): e392. doi:10.1111/csp2.392. Bibcode: 2021ConSP...3E.392S.

- ↑ The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History. A 1: To 1200 (Fifth ed.). Houghton Mifflin. 2000. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-4390-8476-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=aujp0cT_TiEC&pg=PAPA75.

- ↑ Park, Yumi (2012). Mirrors of Clay: Reflections of Ancient Andean Life in Ceramics from the Sam Olden Collection. University Press of Mississippi. p. 49. ISBN 9781617037955.

- ↑ Ocampo López, J. (2007) (in es). Grandes culturas indígenas de América – Great indigenous cultures of the Americas. Bogotá, Colombia: Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A.. p. 231. ISBN 978-958-14-0368-4.

- ↑ Kruschek, M.H. (2003). The evolution of the Bogotá chiefdom: A household view (PDF) (PhD thesis). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "nymy" (in es). Muysc cubun Dictionary Online. http://muysca.cubun.org/nymy.

- ↑ "quyne" (in es). Muysc cubun Dictionary Online. http://muysca.cubun.org/quyne.

- ↑ Metcalf, G.; Flannery, K.V. (1967). "An Olmec "were-jaguar" from the Yucatan Peninsula". American Antiquity 32 (1): 109–111. doi:10.2307/278787.

- ↑ Dapcevich, M. (2018). "Ancient Mayans Probably Kept Jaguars As Pets And Raised Dogs For Food". IFLScience. https://www.iflscience.com/plants-and-animals/ancient-mayans-probably-kept-jaguars-as-pets-and-raised-dogs-for-food/.

- ↑ Saunders, N.J. (1994). "Predators of culture: Jaguar symbolism and Mesoamerican elites". World Archaeology 26 (1): 104–117. doi:10.1080/00438243.1994.9980264.

- ↑ Christenson, A.J. (2007). "The first four men". Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 196–199. ISBN 978-0-8061-3839-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=hJx47n_sm-YC&pg=PAPA196.

- ↑ Benson, Elizabeth P (2013). "The lord, the ruler: Jagaur symbolism in the Americas". in Saunders, Nicholas J.. Icons of Power: Feline Symbolism in the Americas. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 9781136605130.

- ↑ Saunders, Nicholas J. (1994). "Predators of Culture: Jaguar Symbolism and Mesoamerican Elites". World Archaeology 26 (1): 104–117. doi:10.1080/00438243.1994.9980264. ISSN 0043-8243. https://www.jstor.org/stable/124867.

- ↑ Khan, A. (2021). "National symbols: The Coat-Of-Arms". http://www.guyana.org/Handbook/symbols.html.

- ↑ Gutterman, D. (2008). "Amazonas Department (Colombia)". Flag of the World. https://www.fotw.info/flags/co-ama.html.

- ↑ Davies, S. (2007). "Puma power: Argentinian rugby". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport2/hi/rugby_union/5389512.stm.

External links

- "Jaguar Panthera onca". IUCN Cat Specialist Group. http://www.catsg.org/index.php?id=95.

- "Jaguars: Born free". BBC Natural World. 2013. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01q9djl.

- People and Jaguars a Guide for Coexistence

- Felidae Conservation Fund

"Jaguar". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

"Jaguar". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

Wikidata ☰ Q35694 entry

|