Cloud computing security

| This article is part of a series on |

| Computer hacking |

|---|

| History |

| Hacker culture & ethic |

| Conferences |

| Computer crime |

| Hacking tools |

| Practice sites |

| Malware |

| Computer security |

| Groups |

|

| Publications |

Cloud computing security or, more simply, cloud security, refers to a broad set of policies, technologies, applications, and controls utilized to protect virtualized IP, data, applications, services, and the associated infrastructure of cloud computing. It is a sub-domain of computer security, network security, and, more broadly, information security.

Security issues associated with the cloud

Cloud computing and storage provide users with the capabilities to store and process their data in third-party data centers.[1] Organizations use the cloud in a variety of different service models (with acronyms such as SaaS, PaaS, and IaaS) and deployment models (private, public, hybrid, and community).[2]

Security concerns associated with cloud computing are typically categorized in two ways: as security issues faced by cloud providers (organizations providing software-, platform-, or infrastructure-as-a-service via the cloud) and security issues faced by their customers (companies or organizations who host applications or store data on the cloud).[3] The responsibility is shared, however, and is often detailed in a cloud provider's "shared security responsibility model" or "shared responsibility model."[4][5][6] The provider must ensure that their infrastructure is secure and that their clients’ data and applications are protected, while the user must take measures to fortify their application and use strong passwords and authentication measures.[5][6]

When an organization elects to store data or host applications on the public cloud, it loses its ability to have physical access to the servers hosting its information. As a result, potentially sensitive data is at risk from insider attacks. According to a 2010 Cloud Security Alliance report, insider attacks are one of the top seven biggest threats in cloud computing.[7] Therefore, cloud service providers must ensure that thorough background checks are conducted for employees who have physical access to the servers in the data center. Additionally, data centers are recommended to be frequently monitored for suspicious activity.

In order to conserve resources, cut costs, and maintain efficiency, cloud service providers often store more than one customer's data on the same server. As a result, there is a chance that one user's private data can be viewed by other users (possibly even competitors). To handle such sensitive situations, cloud service providers should ensure proper data isolation and logical storage segregation.[2]

The extensive use of virtualization in implementing cloud infrastructure brings unique security concerns for customers or tenants of a public cloud service.[8] Virtualization alters the relationship between the OS and underlying hardware – be it computing, storage or even networking. This introduces an additional layer – virtualization – that itself must be properly configured, managed and secured.[9] Specific concerns include the potential to compromise the virtualization software, or "hypervisor". While these concerns are largely theoretical, they do exist.[10] For example, a breach in the administrator workstation with the management software of the virtualization software can cause the whole data center to go down or be reconfigured to an attacker's liking.

Cloud security controls

Cloud security architecture is effective only if the correct defensive implementations are in place. An efficient cloud security architecture should recognize the issues that will arise with security management and follow all of the best practices, procedures, and guidelines to ensure a secure cloud environment. Security management addresses these issues with security controls. These controls protect cloud environments and are put in place to safeguard any weaknesses in the system and reduce the effect of an attack. While there are many types of controls behind a cloud security architecture, they can usually be found in one of the following categories:

- Deterrent controls

- These controls are administrative mechanisms intended to reduce attacks on a cloud system and are utilized to ensure compliance with external controls. Much like a warning sign on a fence or a property, deterrent controls typically reduce the threat level by informing potential attackers that there will be adverse consequences for them if they proceed.[11] (Some consider them a subset of preventive controls.) Examples of such controls could be considered as policies, procedures, standards, guidelines, laws, and regulations that guide an organization towards security. Although most malicious actors ignore such deterrent controls, such controls are intended to ward off those who are inexperienced or curious about compromising the IT infrastructure of an organization.

- Preventive controls

- The main objective of preventive controls is to strengthen the system against incidents, generally by reducing if not actually eliminating vulnerabilities, as well as preventing unauthorized intruders from accessing or entering the system.[12] This could be achieved by either adding software or feature implementations (such as firewall protection, endpoint protection, and multi-factor authentication), or removing unneeded functionalities so that the attack surface is minimized (as in unikernel applications). Additionally, educating individuals through security awareness training and exercises is included in such controls due to human error being the weakest point of security. Strong authentication of cloud users, for instance, makes it less likely that unauthorized users can access cloud systems, and more likely that cloud users are positively identified. All in all, preventative controls affect the likelihood of a loss event occurring and are intended to prevent or eliminate the systems’ exposure to malicious action.

- Detective controls

- Detective controls are intended to detect and react appropriately to any incidents that occur. In the event of an attack, a detective control will signal the preventative or corrective controls to address the issue. Detective security controls function not only when such an activity is in progress and after it has occurred. System and network security monitoring, including intrusion detection and prevention arrangements, are typically employed to detect attacks on cloud systems and the supporting communications infrastructure. Most organizations acquire or create a dedicated security operations center (SOC), where dedicated members continuously monitor the organization’s IT infrastructure through logs and Security Information and Event Management (SIEM) software. SIEMs are security solutions that help organizations and security teams analyze “log data in real-time for swift detection of security incidents.”[13] SIEMS are not the only examples of detective controls. There are also Physical security controls, Intrusion detection systems, and anti-virus/anti-malware tools, which all have different functions centered around the exact purpose of detecting security compromises within an IT infrastructure.

- Corrective controls

- Corrective controls reduce the consequences of an incident, generally by limiting the damage. Such controls include technical, physical, and administrative measures that occur during or after an incident to restore the systems or resources to their previous state after a security incident.[14] There are plenty of examples of corrective controls, both physical and technical. For instance, re-issuing an access card or repairing physical damage can be considered corrective controls. However, technical controls such as terminating a process and administrative controls such as implementing an incident response plan could also be considered corrective controls. Corrective controls are focused on recovering and repairing any damage caused by a security incident or unauthorized activity. The value is needed to change the function of security.

Dimensions of cloud security

Cloud security engineering is characterized by the security layers, plan, design, programming, and best practices that exist inside a cloud security arrangement. Cloud security engineering requires the composed and visual model (design and UI) to be characterized by the tasks inside the Cloud. This cloud security engineering process includes such things as access to the executives, techniques, and controls to ensure applications and information. It also includes ways to deal with and keep up with permeability, consistency, danger stance, and by and large security. Processes for imparting security standards into cloud administrations and activities assume an approach that fulfills consistent guidelines and essential framework security parts.[15]

For interest in Cloud advancements to be viable, companies should recognize the various parts of the Cloud and how they remain to impact and help them. These interests may include investments in cloud computing and security, for example. This of course leads to leads to driving push for the Cloud advancements to succeed.

Though the idea of cloud computing isn't new, associations are increasingly enforcing it because of its flexible scalability, relative trustability, and cost frugality of services. However, despite its rapid-fire relinquishment in some sectors and disciplines, it's apparent from exploration and statistics that security-related pitfalls are the most conspicuous hedge to its wide relinquishment.[citation needed]

It is generally recommended that information security controls be selected and implemented according to and in proportion to the risks, typically by assessing the threats, vulnerabilities and impacts. Cloud security concerns can be grouped in various ways; Gartner named seven[16] while the Cloud Security Alliance identified twelve areas of concern.[17] Cloud access security brokers (CASBs) are software that sits between cloud users and cloud applications to provide visibility into cloud application usage, data protection and governance to monitor all activity and enforce security policies.[18]

Security and privacy

Any service without a "hardened" environment is considered a "soft" target. Virtual servers should be protected just like a physical server against data leakage, malware, and exploited vulnerabilities. "Data loss or leakage represents 24.6% and cloud related malware 3.4% of threats causing cloud outages”.[19]

Identity management

Every enterprise will have its own identity management system to control access to information and computing resources. Cloud providers either integrate the customer's identity management system into their own infrastructure, using federation or SSO technology or a biometric-based identification system,[1] or provide an identity management system of their own.[20] CloudID,[1] for instance, provides privacy-preserving cloud-based and cross-enterprise biometric identification. It links the confidential information of the users to their biometrics and stores it in an encrypted fashion. Making use of a searchable encryption technique, biometric identification is performed in the encrypted domain to make sure that the cloud provider or potential attackers do not gain access to any sensitive data or even the contents of the individual queries.[1]

Physical security

Cloud service providers physically secure the IT hardware (servers, routers, cables etc.) against unauthorized access, interference, theft, fires, floods etc. and ensure that essential supplies (such as electricity) are sufficiently robust to minimize the possibility of disruption. This is normally achieved by serving cloud applications from professionally specified, designed, constructed, managed, monitored and maintained data centers.

Personnel security

Various information security concerns relating to the IT and other professionals associated with cloud services are typically handled through pre-, para- and post-employment activities such as security screening potential recruits, security awareness and training programs, and proactive.

Privacy

Providers ensure that all critical data (credit card numbers, for example) are masked or encrypted and that only authorized users have access to data in its entirety. Moreover, digital identities and credentials must be protected as should any data that the provider collects or produces about customer activity in the cloud.

Penetration testing

Penetration testing is the process of performing offensive security tests on a system, service, or computer network to find security weaknesses in it. Since the cloud is a shared environment with other customers or tenants, following penetration testing rules of engagement step-by-step is a mandatory requirement. Scanning and penetration testing from inside or outside the cloud should be authorized by the cloud provider. Violation of acceptable use policies can lead to termination of the service.[21]

Cloud vulnerability and penetration testing

Scanning the cloud from outside and inside using free or commercial products is crucial because without a hardened environment your service is considered a soft target. Virtual servers should be hardened just like a physical server against data leakage, malware, and exploited vulnerabilities. "Data loss or leakage represents 24.6% and cloud-related malware 3.4% of threats causing cloud outages”

Scanning and penetration testing from inside or outside the cloud must be authorized by the cloud provider. Since the cloud is a shared environment with other customers or tenants, following penetration testing rules of engagement step-by-step is a mandatory requirement. Violation of acceptable use policies can lead to the termination of the service. Some key terminology to grasp when discussing penetration testing is the difference between application and network layer testing. Understanding what is asked of you as the tester is sometimes the most important step in the process. The network-layer testing refers to testing that includes internal/external connections as well as the interconnected systems throughout the local network. Oftentimes, social engineering attacks are carried out, as the most vulnerable link in security is often the employee.

White-box testing

Testing under the condition that the “attacker” has full knowledge of the internal network, its design, and implementation.

Grey-box testing

Testing under the condition that the “attacker” has partial knowledge of the internal network, its design, and implementation.

Black-box testing

Testing under the condition that the “attacker” has no prior knowledge of the internal network, its design, and implementation.

Data security

There are numerous security threats associated with cloud data services. This includes traditional threats and non-traditional threats. Traditional threats include: network eavesdropping, illegal invasion, and denial of service attacks, but also specific cloud computing threats, such as side channel attacks, virtualization vulnerabilities, and abuse of cloud services. In order to mitigate these threats security controls often rely on monitoring the three areas of the CIA triad. The CIA Triad refers to confidentiality (including access controllability which can be further understood from the following.[22]), integrity and availability.

It is important to note that many effective security measures cover several or all of the three categories. Encryption for example can be used to prevent unauthorized access, and also ensure integrity of the data). Backups on the other hand generally cover integrity and availability and firewalls only cover confidentiality and access controllability.[23]

Confidentiality

Data confidentiality is the property in that data contents are not made available or disclosed to illegal users. Outsourced data is stored in a cloud and out of the owners' direct control. Only authorized users can access the sensitive data while others, including CSPs, should not gain any information about the data. Meanwhile, data owners expect to fully utilize cloud data services, e.g., data search, data computation, and data sharing, without the leakage of the data contents to CSPs or other adversaries. Confidentiality refers to how data must be kept strictly confidential to the owner of said data

An example of security control that covers confidentiality is encryption so that only authorized users can access the data. Symmetric or asymmetric key paradigm can be used for encryption.[24]

Access controllability

Access controllability means that a data owner can perform the selective restriction of access to their data outsourced to the cloud. Legal users can be authorized by the owner to access the data, while others can not access it without permission. Further, it is desirable to enforce fine-grained access control to the outsourced data, i.e., different users should be granted different access privileges with regard to different data pieces. The access authorization must be controlled only by the owner in untrusted cloud environments.

Access control can also be referred to as availability. While unauthorized access should be strictly prohibited, access for administrative or even consumer uses should be allowed but monitored as well. Availability and Access control ensure that the proper amount of permissions is granted to the correct persons.

Integrity

Data integrity demands maintaining and assuring the accuracy and completeness of data. A data owner always expects that her or his data in a cloud can be stored correctly and trustworthy. It means that the data should not be illegally tampered with, improperly modified, deliberately deleted, or maliciously fabricated. If any undesirable operations corrupt or delete the data, the owner should be able to detect the corruption or loss. Further, when a portion of the outsourced data is corrupted or lost, it can still be retrieved by the data users. Effective integrity security controls go beyond protection from malicious actors and protect data from unintentional alterations as well.

An example of security control that covers integrity is automated backups of information.

Risks and vulnerabilities of Cloud Computing

While cloud computing is on the cutting edge of information technology there are risks and vulnerabilities to consider before investing fully in it. Security controls and services do exist for the cloud but as with any security system they are not guaranteed to succeed. Furthermore, some risks extend beyond asset security and may involve issues in productivity and even privacy as well.[25]

Privacy Concerns

Cloud computing is still an emerging technology and thus is developing in relatively new technological structures. As a result, all cloud services must undertake Privacy Impact Assessments or PIAs before releasing their platform. Consumers as well that intend to use clouds to store their customer's data must also be aware of the vulnerabilities of having non-physical storage for private information.[26]

Unauthorized Access to Management interface

Due to the autonomous nature of the cloud, consumers are often given management interfaces to monitor their databases. By having controls in such a congregated location and by having the interface be easily accessible for convenience for users, there is a possibility that a single actor could gain access to the cloud's management interface; giving them a great deal of control and power over the database.[27]

Data Recovery Vulnerabilities

The cloud's capabilities with allocating resources as needed often result in resources in memory and otherwise being recycled to another user at a later event. For these memory or storage resources, it could be possible for current users to access information left by previous ones.[27]

Internet Vulnerabilities

The cloud requires an internet connection and therefore internet protocols to access. Therefore, it is open to many internet protocol vulnerabilities such as man-in-the-middle attacks. Furthermore, by having a heavy reliance on internet connectivity, if the connection fails consumers will be completely cut off from any cloud resources.[27]

Encryption Vulnerabilities

Cryptography is an ever-growing field and technology. What was secure 10 years ago may be considered a significant security risk by today's standards. As technology continues to advance and older technologies grow old, new methods of breaking encryptions will emerge as well as fatal flaws in older encryption methods. Cloud providers must keep up to date with their encryption as the data they typically contain is especially valuable.[28]

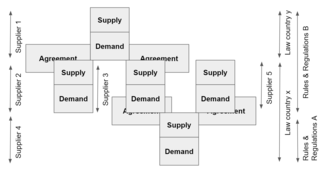

Legal issues

Privacy legislation often varies from country to country. By having information stored via the cloud it is difficult to determine under which jurisdictions the data falls under. Transborder clouds are especially popular given that the largest companies transcend several countries. Other legal dilemmas from the ambiguity of the cloud refer to how there is a difference in privacy regulation between information shared between and information shared inside of organizations.[26]

Attacks

There are several different types of attacks on cloud computing, one that is still very much untapped is infrastructure compromise. Though not completely known it is listed as the attack with the highest amount of payoff.[29] What makes this so dangerous is that the person carrying out the attack is able to gain a level of privilege of having essentially root access to the machine. It is very hard to defend against attacks like these because they are so unpredictable and unknown, attacks of this type are also called zero day exploits because they are difficult to defend against since the vulnerabilities were previously unknown and unchecked until the attack has already occurred.

DoS attacks aim to have systems be unavailable to their users. Since cloud computing software is used by large numbers of people, resolving these attacks is increasingly difficult. Now with cloud computing on the rise, this has left new opportunities for attacks because of the virtualization of data centers and cloud services being utilized more.[30]

With the global pandemic that started early in 2020 taking effect, there was a massive shift to remote work, because of this companies became more reliant on the cloud. This massive shift has not gone unnoticed, especially by cybercriminals and bad actors, many of which saw the opportunity to attack the cloud because of this new remote work environment. Companies have to constantly remind their employees to keep constant vigilance especially remotely. Constantly keeping up to date with the latest security measures and policies, mishaps in communication are some of the things that these cybercriminals are looking for and will prey upon.

Moving work to the household was critical for workers to be able to continue, but as the move to remote work happened, several security issues arose quickly. The need for data privacy, using applications, personal devices, and the internet all came to the forefront. The pandemic has had large amounts of data being generated especially in the healthcare sector. Big data is accrued for the healthcare sector now more than ever due to the growing coronavirus pandemic. The cloud has to be able to organize and share the data with its users securely. Quality of data looks for four things: accuracy, redundancy, completeness and consistency.[31]

Users had to think about the fact that massive amounts of data are being shared globally. Different countries have certain laws and regulations that have to be adhered to. Differences in policy and jurisdiction give rise to the risk involved with the cloud. Workers are using their personal devices more now that they are working from home. Criminals see this increase as an opportunity to exploit people, software is developed to infect people's devices and gain access to their cloud. The current pandemic has put people in a situation where they are incredibly vulnerable and susceptible to attacks. The change to remote work was so sudden that many companies simply were unprepared to deal with the tasks and subsequent workload they have found themselves deeply entrenched in. Tighter security measures have to be put in place to ease that newfound tension within organizations.

The attacks that can be made on cloud computing systems include man-in-the middle attacks, phishing attacks, authentication attacks, and malware attacks. One of the largest threats is considered to be malware attacks, such as Trojan horses.

Recent research conducted in 2022 has revealed that the Trojan horse injection method is a serious problem with harmful impacts on cloud computing systems. A Trojan attack on cloud systems tries to insert an application or service into the system that can impact the cloud services by changing or stopping the functionalities. When the cloud system identifies the attacks as legitimate, the service or application is performed which can damage and infect the cloud system.[32]

Encryption

Some advanced encryption algorithms which have been applied to cloud computing increase the protection of privacy. In a practice called crypto-shredding, the keys can simply be deleted when there is no more use of the data.

Attribute-based encryption (ABE)

Attribute-based encryption is a type of public-key encryption in which the secret key of a user and the ciphertext are dependent upon attributes (e.g. the country in which he lives, or the kind of subscription he has). In such a system, the decryption of a ciphertext is possible only if the set of attributes of the user key matches the attributes of the ciphertext.

Some of the strengths of Attribute-based encryption are that it attempts to solve issues that exist in current public-key infrastructure(PKI) and identity-based encryption(IBE) implementations. By relying on attributes ABE circumvents needing to share keys directly, as with PKI, as well as having to know the identity of the receiver, as with IBE.

These benefits come at a cost as ABE suffers from the decryption key re-distribution problem. Since decryption keys in ABE only contain information regarding access structure or the attributes of the user it is hard to verify the user's actual identity. Thus malicious users can intentionally leak their attribute information so that unauthorized users can imitate and gain access.[33]

Ciphertext-policy ABE (CP-ABE)

Ciphertext-policy ABE (CP-ABE) is a type of public-key encryption. In the CP-ABE, the encryptor controls the access strategy. The main research work of CP-ABE is focused on the design of the access structure. A Ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption scheme consists of four algorithms: Setup, Encrypt, KeyGen, and Decrypt.[34] The Setup algorithm takes security parameters and an attribute universe description as input and outputs public parameters and a master key. The encryption algorithm takes data as input. It then encrypts it to produce ciphertext that only a user that possesses a set of attributes that satisfies the access structure will decrypt the message. The KeyGen algorithm then takes the master key and the user's attributes to develop a private key. Finally, the Decrypt algorithm takes the public parameters, the ciphertext, the private key, and user attributes as input. With this information, the algorithm first checks if the users’ attributes satisfy the access structure and then decrypts the ciphertext to return the data.

Key-policy ABE (KP-ABE)

Key-policy Attribute-Based Encryption, or KP-ABE, is an important type of Attribute-Based Encryption. KP-ABE allows senders to encrypt their messages under a set of attributes, much like any Attribute Based Encryption system. For each encryption, private user keys are then generated which contain decryption algorithms for deciphering the message and these private user keys grant users access to specific messages that they correspond to. In a KP-ABE system, ciphertexts, or the encrypted messages, are tagged by the creators with a set of attributes, while the user's private keys are issued that specify which type of ciphertexts the key can decrypt.[35] The private keys control which ciphertexts a user is able to decrypt.[36] In KP-ABE, the attribute sets are used to describe the encrypted texts and the private keys are associated to the specified policy that users will have for the decryption of the ciphertexts. A drawback to KP-ABE is that in KP-ABE the encryptor does not control who has access to the encrypted data, except through descriptive attributes, which creates a reliance on the key-issuer granting and denying access to users. Hence, the creation of other ABE systems such as Ciphertext-Policy Attribute-Based Encryption.[37]

Fully homomorphic encryption (FHE)

Fully Homomorphic Encryption is a cryptosystem that supports arbitrary computation on ciphertext and also allows computing sum and product for the encrypted data without decryption. Another interesting feature of Fully Homomorphic Encryption or FHE for short is that it allows operations to be executed without the need for a secret key.[38] FHE has been linked not only to cloud computing but to electronic voting as well. Fully Homomorphic Encryption has been especially helpful with the development of cloud computing and computing technologies. However, as these systems are developing the need for cloud security has also increased. FHE aims to secure data transmission as well as cloud computing storage with its encryption algorithms.[39] Its goal is to be a much more secure and efficient method of encryption on a larger scale to handle the massive capabilities of the cloud.

Searchable encryption (SE)

Searchable encryption is a cryptographic system that offers secure search functions over encrypted data.[40][41] SE schemes can be classified into two categories: SE based on secret-key (or symmetric-key) cryptography, and SE based on public-key cryptography. In order to improve search efficiency, symmetric-key SE generally builds keyword indexes to answer user queries. This has the obvious disadvantage of providing multimodal access routes for unauthorized data retrieval, bypassing the encryption algorithm by subjecting the framework to alternative parameters within the shared cloud environment.[42]

Compliance

Numerous laws and regulations pertaining to the storage and use of data. In the US these include privacy or data protection laws, Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA), and Children's Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998, among others. Similar standards exist in other jurisdictions, e.g. Singapore's Multi-Tier Cloud Security Standard.

Similar laws may apply in different legal jurisdictions and may differ quite markedly from those enforced in the US. Cloud service users may often need to be aware of the legal and regulatory differences between the jurisdictions. For example, data stored by a cloud service provider may be located in, say, Singapore and mirrored in the US.[43]

Many of these regulations mandate particular controls (such as strong access controls and audit trails) and require regular reporting. Cloud customers must ensure that their cloud providers adequately fulfill such requirements as appropriate, enabling them to comply with their obligations since, to a large extent, they remain accountable.

- Business continuity and data recovery

- Cloud providers have business continuity and data recovery plans in place to ensure that service can be maintained in case of a disaster or an emergency and that any data loss will be recovered.[44] These plans may be shared with and reviewed by their customers, ideally dovetailing with the customers' own continuity arrangements. Joint continuity exercises may be appropriate, simulating a major Internet or electricity supply failure for instance.

- Log and audit trail

- In addition to producing logs and audit trails, cloud providers work with their customers to ensure that these logs and audit trails are properly secured, maintained for as long as the customer requires, and are accessible for the purposes of forensic investigation (e.g., eDiscovery).

- Unique compliance requirements

- In addition to the requirements to which customers are subject, the data centers used by cloud providers may also be subject to compliance requirements. Using a cloud service provider (CSP) can lead to additional security concerns around data jurisdiction since customer or tenant data may not remain on the same system, in the same data center, or even within the same provider's cloud.[45]

- The European Union’s GDPR has introduced new compliance requirements for customer data.

Legal and contractual issues

Aside from the security and compliance issues enumerated above, cloud providers and their customers will negotiate terms around liability (stipulating how incidents involving data loss or compromise will be resolved, for example), intellectual property, and end-of-service (when data and applications are ultimately returned to the customer). In addition, there are considerations for acquiring data from the cloud that may be involved in litigation.[46] These issues are discussed in service-level agreements (SLA).

Public records

Legal issues may also include records-keeping requirements in the public sector, where many agencies are required by law to retain and make available electronic records in a specific fashion. This may be determined by legislation, or law may require agencies to conform to the rules and practices set by a records-keeping agency. Public agencies using cloud computing and storage must take these concerns into account.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Haghighat, Mohammad; Zonouz, Saman; Abdel-Mottaleb, Mohamed (November 2015). "CloudID: Trustworthy cloud-based and cross-enterprise biometric identification". Expert Systems with Applications 42 (21): 7905–7916. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2015.06.025.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Srinivasan, Madhan Kumar; Sarukesi, K.; Rodrigues, Paul; Manoj, M. Sai; Revathy, P. (2012). "State-of-the-art cloud computing security taxonomies". Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communications and Informatics - ICACCI '12. pp. 470–476. doi:10.1145/2345396.2345474. ISBN 978-1-4503-1196-0.

- ↑ "Swamp Computing a.k.a. Cloud Computing". Web Security Journal. 2009-12-28. http://security.sys-con.com/node/1231725.

- ↑ "Cloud Controls Matrix v4" (xlsx). Cloud Security Alliance. 15 March 2021. https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/artifacts/cloud-controls-matrix-v4/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Tozzi, C. (24 September 2020). "Avoiding the Pitfalls of the Shared Responsibility Model for Cloud Security". Pal Alto Blog. Palo Alto Networks. https://www.paloaltonetworks.com/blog/prisma-cloud/pitfalls-shared-responsibility-cloud-security/.

- ↑ "Top Threats to Cloud Computing v1.0". Cloud Security Alliance. March 2010. http://www.itsecure.hu/library/file/Biztons%C3%A1gi%20%C3%BAtmutat%C3%B3k/Felh%C5%91%20szolg%C3%A1ltat%C3%A1sok/Top%20threats%20to%20cloud%20computing%20v1_0.pdf.

- ↑ Winkler, Vic. "Cloud Computing: Virtual Cloud Security Concerns". Technet Magazine, Microsoft. https://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/magazine/hh641415.aspx.

- ↑ Hickey, Kathleen (18 March 2010). "Dark Cloud: Study finds security risks in virtualization". Government Security News. http://gcn.com/articles/2010/03/18/dark-cloud-security.aspx.

- ↑ Winkler, Joachim R. (2011). Securing the Cloud: Cloud Computer Security Techniques and Tactics. Elsevier. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-59749-592-9.

- ↑ Andress, J. (2014). Deterrent Control - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Retrieved October 14, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-science/deterrent-control

- ↑ Virtue, T., & Rainey, J. (2015). Preventative Control - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics. Retrieved October 13, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-science/preventative-control

- ↑ Marturano, G. (2020b, December 4). Detective Security Controls. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://lifars.com/2020/12/detective-security-controls/

- ↑ Walkowski, D. (2019, August 22). What are Security Controls? Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.f5.com/labs/articles/education/what-are-security-controls

- ↑ "Cloud Security Architecture". GuidePoint Security LLC. 2023. https://www.guidepointsecurity.com/education-center/cloud-security-architecture.

- ↑ "Gartner: Seven cloud-computing security risks". InfoWorld. 2008-07-02. http://www.infoworld.com/d/security-central/gartner-seven-cloud-computing-security-risks-853. Retrieved 2010-01-25.

- ↑ "Top Threats to Cloud Computing Plus: Industry Insights". Cloud Security Alliance. 2017-10-20. https://cloudsecurityalliance.org/artifacts/top-threats-cloud-computing-plus-industry-insights/.

- ↑ "What is a CASB (Cloud Access Security Broker)?". CipherCloud. https://www.ciphercloud.com/what-is-a-casb.

- ↑ Ahmad Dahari Bin Jarno; Shahrin Bin Baharom; Maryam Shahpasand (2017). "Limitations and challenges on Security Cloud Testing". Journal of Applied Technology and Innovation 1 (2): 89-90. https://www.apu.edu.my/ejournals/jati/journal/JATI-VOLUME_1-ISSUE_2-2017.pdf.

- ↑ Chickowski, E. (25 October 2013). "Identity Management In The Cloud". Informa PLC. https://www.darkreading.com/cybersecurity-analytics/identity-management-in-the-cloud.

- ↑ Guarda, Teresa; Orozco, Walter; Augusto, Maria Fernanda; Morillo, Giovanna; Navarrete, Silvia Arévalo; Pinto, Filipe Mota (2016). "Penetration Testing on Virtual Environments". Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information and Network Security - ICINS '16. pp. 9–12. doi:10.1145/3026724.3026728. ISBN 978-1-4503-4796-9.

- ↑ Tang, Jun; Cui, Yong; Li, Qi; Ren, Kui; Liu, Jiangchuan; Buyya, Rajkumar (28 July 2016). "Ensuring Security and Privacy Preservation for Cloud Data Services". ACM Computing Surveys 49 (1): 1–39. doi:10.1145/2906153.

- ↑ "Confidentiality, Integrity and Availability - The CIA Triad" (in en-US). 2018-08-04. https://www.certmike.com/confidentiality-integrity-and-availability-the-cia-triad/.

- ↑ Tabrizchi, Hamed; Kuchaki Rafsanjani, Marjan (2020-12-01). "A survey on security challenges in cloud computing: issues, threats, and solutions" (in en). The Journal of Supercomputing 76 (12): 9493–9532. doi:10.1007/s11227-020-03213-1. ISSN 1573-0484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-020-03213-1.

- ↑ Carroll, Mariana; van der Merwe, Alta; Kotzé, Paula (August 2011). "Secure cloud computing: Benefits, risks and controls". 2011 Information Security for South Africa. pp. 1–9. doi:10.1109/ISSA.2011.6027519. ISBN 978-1-4577-1481-8.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Svantesson, Dan; Clarke, Roger (July 2010). "Privacy and consumer risks in cloud computing". Computer Law & Security Review 26 (4): 391–397. doi:10.1016/j.clsr.2010.05.005.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Grobauer, Bernd; Walloschek, Tobias; Stocker, Elmar (March 2011). "Understanding Cloud Computing Vulnerabilities". IEEE Security Privacy 9 (2): 50–57. doi:10.1109/MSP.2010.115.

- ↑ Rukavitsyn, Andrey N.; Borisenko, Konstantin A.; Holod, Ivan I.; Shorov, Andrey V. (2017). "The method of ensuring confidentiality and integrity data in cloud computing". 2017 XX IEEE International Conference on Soft Computing and Measurements (SCM). pp. 272–274. doi:10.1109/SCM.2017.7970558. ISBN 978-1-5386-1810-3.

- ↑ Yao, Huiping; Shin, Dongwan (2013). "Towards preventing QR code based attacks on android phone using security warnings". Proceedings of the 8th ACM SIGSAC symposium on Information, computer and communications security - ASIA CCS '13. p. 341. doi:10.1145/2484313.2484357. ISBN 9781450317672.

- ↑ Iqbal, Salman; Mat Kiah, Miss Laiha; Dhaghighi, Babak; Hussain, Muzammil; Khan, Suleman; Khan, Muhammad Khurram; Raymond Choo, Kim-Kwang (October 2016). "On cloud security attacks: A taxonomy and intrusion detection and prevention as a service". Journal of Network and Computer Applications 74: 98–120. doi:10.1016/j.jnca.2016.08.016.

- ↑ Alashhab, Ziyad R.; Anbar, Mohammed; Singh, Manmeet Mahinderjit; Leau, Yu-Beng; Al-Sai, Zaher Ali; Abu Alhayja’a, Sami (March 2021). "Impact of coronavirus pandemic crisis on technologies and cloud computing applications". Journal of Electronic Science and Technology 19 (1): 100059. doi:10.1016/j.jnlest.2020.100059.

- ↑ Kanaker, Hasan; Karim, Nader Abdel; Awwad, Samer A. B.; Ismail, Nurul H. A.; Zraqou, Jamal; Ali, Abdulla M. F. Al (2022-12-20). "Trojan Horse Infection Detection in Cloud Based Environment Using Machine Learning" (in en). International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM) 16 (24): 81–106. doi:10.3991/ijim.v16i24.35763. ISSN 1865-7923. https://online-journals.org/index.php/i-jim/article/view/35763.

- ↑ Xu, Shengmin; Yuan, Jiaming; Xu, Guowen; Li, Yingjiu; Liu, Ximeng; Zhang, Yinghui; Ying, Zuobin (October 2020). "Efficient ciphertext-policy attribute-based encryption with blackbox traceability". Information Sciences 538: 19–38. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2020.05.115. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sis_research/5179.

- ↑ Bethencourt, John; Sahai, Amit; Waters, Brent (May 2007). "2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP '07)". 2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP '07). pp. 321–334. doi:10.1109/SP.2007.11. ISBN 978-0-7695-2848-9.

- ↑ Wang, Changji; Luo, Jianfa (2013). "An Efficient Key-Policy Attribute-Based Encryption Scheme with Constant Ciphertext Length". Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2013: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2013/810969.

- ↑ Wang, Chang-Ji; Luo, Jian-Fa (November 2012). "A Key-policy Attribute-based Encryption Scheme with Constant Size Ciphertext". 2012 Eighth International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Security. pp. 447–451. doi:10.1109/CIS.2012.106. ISBN 978-1-4673-4725-9.

- ↑ Bethencourt, John; Sahai, Amit; Waters, Brent (May 2007). "2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP '07)". 2007 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP '07). pp. 321–334. doi:10.1109/SP.2007.11. ISBN 978-0-7695-2848-9.

- ↑ Armknecht, Frederik; Katzenbeisser, Stefan; Peter, Andreas (2012). "Shift-Type Homomorphic Encryption and Its Application to Fully Homomorphic Encryption". Progress in Cryptology - AFRICACRYPT 2012. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 7374. pp. 234–251. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31410-0_15. ISBN 978-3-642-31409-4. https://ris.utwente.nl/ws/files/5322305/andreas.pdf.

- ↑ Zhao, Feng; Li, Chao; Liu, Chun Feng (2014). "A cloud computing security solution based on fully homomorphic encryption". 16th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology. pp. 485–488. doi:10.1109/icact.2014.6779008. ISBN 978-89-968650-3-2.

- ↑ Wang, Qian; He, Meiqi; Du, Minxin; Chow, Sherman S. M.; Lai, Russell W. F.; Zou, Qin (1 May 2018). "Searchable Encryption over Feature-Rich Data". IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 15 (3): 496–510. doi:10.1109/TDSC.2016.2593444.

- ↑ Sahayini, T (2016). "Enhancing the security of modern ICT systems with multimodal biometric cryptosystem and continuous user authentication". International Journal of Information and Computer Security 8 (1): 55. doi:10.1504/IJICS.2016.075310.

- ↑ "Managing legal risks arising from cloud computing". DLA Piper. 29 August 2014. http://www.technologyslegaledge.com/2014/08/29/managing-legal-risks-arising-from-cloud-computing/.

- ↑ "It's Time to Explore the Benefits of Cloud-Based Disaster Recovery". Dell.com. http://content.dell.com/us/en/enterprise/d/large-business/benefits-cloud-based-recovery.aspx.

- ↑ Winkler, Joachim R. (2011). Securing the Cloud: Cloud Computer Security Techniques and Tactics. Elsevier. pp. 65, 68, 72, 81, 218–219, 231, 240. ISBN 978-1-59749-592-9.

- ↑ Adams, Richard (2013). "The emergence of cloud storage and the need for a new digital forensic process model". in Ruan, Keyun. Cybercrime and Cloud Forensics: Applications for Investigation Processes. Information Science Reference. pp. 79–104. ISBN 978-1-4666-2662-1. https://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/19431/1/emergence_of_cloud_storage.pdf.

Further reading

- Mowbray, Miranda (15 April 2009). "The Fog over the Grimpen Mire: Cloud Computing and the Law". SCRIPT-ed 6 (1): 132–146. doi:10.2966/scrip.060109.132.

- Mather, Tim; Kumaraswamy, Subra; Latif, Shahed (2009). Cloud Security and Privacy: An Enterprise Perspective on Risks and Compliance. O'Reilly Media, Inc.. ISBN 9780596802769.

- Winkler, Vic (2011). Securing the Cloud: Cloud Computer Security Techniques and Tactics. Elsevier. ISBN 9781597495929.

- Ottenheimer, Davi (2012). Securing the Virtual Environment: How to Defend the Enterprise Against Attack. Wiley. ISBN 9781118155486.

- BS ISO/IEC 27017: "Information technology. Security techniques. Code of practice for information security controls based on ISO/IEC 27002 for cloud services." (2015)

- BS ISO/IEC 27018: "Information technology. Security techniques. Code of practice for protection of personally identifiable information (PII) in public clouds acting as PII processors." (2014)

- BS ISO/IEC 27036-4: "Information technology. Security techniques. Information security for supplier relationships. Guidelines for security of cloud services" (2016)

External links

- Cloud Security Alliance

- Check Point Cloud Security

- Cloud Security Solutions

- Why cloud security requires multiple layers

- The Beginner's Guide to Cloud Security

- DoD Cloud Computing Security Requirements Guide (CC SRG)

Archive

|