Company:BHP

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

BHP Office Tower in Perth, Western Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Dual-listed public company | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

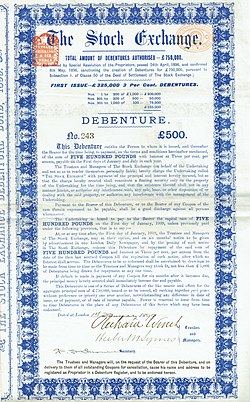

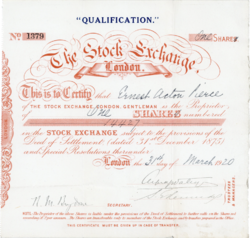

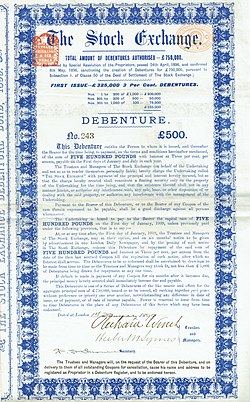

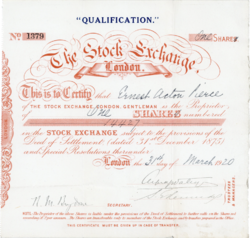

Short description: Stock exchange in the City of London

London Stock Exchange (LSE) is a stock exchange in the City of London, England , United Kingdom. As of August 2023,[update] the total market value of all companies trading on the LSE stood at $3.18 trillion.[3] Its current premises are situated in Paternoster Square close to St Paul's Cathedral in the City of London. Since 2007, it has been part of the London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG (LSE: [Script error: No such module "Stock tickers/LSE". LSEG])).[4] The LSE is the most-valued stock exchange in Europe as of 2023.[5] According to the 2020 Office for National Statistics report, approximately 12% of UK-resident individuals reported having investments in stocks and shares.[6] According to the 2020 Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) report, approximately 15% of UK adults reported having investments in stocks and shares.[7] HistoryCoffee HouseThe Royal Exchange had been founded by English financier Thomas Gresham and Sir Richard Clough on the model of the Antwerp Bourse. It was opened by Elizabeth I of England in 1571.[8][9] During the 17th century, stockbrokers were not allowed in the Royal Exchange due to their rude manners. They had to operate from other establishments in the vicinity, notably Jonathan's Coffee-House. At that coffee house, a broker named John Castaing started listing the prices of a few commodities, such as salt, coal, paper, and exchange rates in 1698. Originally, this was not a daily list and was only published a few days of the week.[10] This list and activity was later moved to Garraway's coffee house. Public auctions during this period were conducted for the duration that a length of tallow candle could burn; these were known as "by inch of candle" auctions. As stocks grew, with new companies joining to raise capital, the royal court also raised some monies. These are the earliest evidence of organised trading in marketable securities in London. Royal ExchangeAfter Gresham's Royal Exchange building was destroyed in the Great Fire of London, it was rebuilt and re-established in 1669. This was a move away from coffee houses and a step towards the modern model of stock exchange.[11] The Royal Exchange housed not only brokers but also merchants and merchandise. This was the birth of a regulated stock market, which had teething problems in the shape of unlicensed brokers. In order to regulate these, Parliament passed an Act in 1697 that levied heavy penalties, both financial and physical, on those brokering without a licence. It also set a fixed number of brokers (at 100), but this was later increased as the size of the trade grew. This limit led to several problems, one of which was that traders began leaving the Royal Exchange, either by their own decision or through expulsion, and started dealing in the streets of London. The street in which they were now dealing was known as 'Exchange Alley', or 'Change Alley'; it was suitably placed close to the Bank of England. Parliament tried to regulate this and ban the unofficial traders from the Change streets. Traders became weary of "bubbles" when companies rose quickly and fell, so they persuaded Parliament to pass a clause preventing "unchartered" companies from forming. After the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), trade at Jonathan's Coffee House boomed again. In 1773, Jonathan, together with 150 other brokers, formed a club and opened a new and more formal "Stock Exchange" in Sweeting's Alley. This now had a set entrance fee, by which traders could enter the stock room and trade securities. It was, however, not an exclusive location for trading, as trading also occurred in the Rotunda of the Bank of England. Fraud was also rife during these times and in order to deter such dealings, it was suggested that users of the stock room pay an increased fee. This was not met well and ultimately, the solution came in the form of annual fees and turning the Exchange into a Subscription room. The Subscription room created in 1801 was the first regulated exchange in London, but the transformation was not welcomed by all parties. On the first day of trading, non-members had to be expelled by a constable. In spite of the disorder, a new and bigger building was planned, at Capel Court. William Hammond laid the first foundation stone for the new building on 18 May. It was finished on 30 December when "The Stock Exchange" was incised on the entrance. First Rule Book In the Exchange's first operating years, on several occasions there was no clear set of regulations or fundamental laws for the Capel Court trading. In February 1812, the General Purpose Committee confirmed a set of recommendations, which later became the foundation of the first codified rule book of the Exchange. Even though the document was not a complex one, topics such as settlement and default were, in fact, quite comprehensive. With its new governmental commandments[12] and increasing trading volume, the Exchange was progressively becoming an accepted part of the financial life in the city. In spite of continuous criticism from newspapers and the public, the government used the Exchange's organised market (and would most likely not have managed without it) to raise the enormous amount of money required for the wars against Napoleon. Foreign and regional exchangesAfter the war and facing a booming world economy, foreign lending to countries such as Brazil, Peru and Chile was a growing market. Notably, the Foreign Market at the Exchange allowed for merchants and traders to participate, and the Royal Exchange hosted all transactions where foreign parties were involved. The constant increase in overseas business eventually meant that dealing in foreign securities had to be allowed within all of the Exchange's premises. Just as London enjoyed growth through international trade, the rest of Great Britain also benefited from the economic boom. Two other cities, in particular, showed great business development: Liverpool and Manchester. Consequently, in 1836 both the Manchester and Liverpool stock exchanges were opened. Some stock prices sometimes rose by 10%, 20% or even 30% in a week. These were times when stockbroking was considered a real business profession, and such attracted many entrepreneurs. Nevertheless, with booms came busts, and in 1835 the "Spanish panic" hit the markets, followed by a second one two years later. The Exchange before the World Wars By June 1853, both participating members and brokers were taking up so much space that the Exchange was now uncomfortably crowded, and continual expansion plans were taking place. Having already been extended west, east, and northwards, it was then decided the Exchange needed an entire new establishment. Thomas Allason was appointed as the main architect, and in March 1854, the new brick building inspired from the Great Exhibition stood ready. This was a huge improvement in both surroundings and space, with twice the floor space available. By the late 1800s, the telephone, ticker tape, and the telegraph had been invented. Those new technologies led to a revolution in the work of the Exchange. First World War As the financial centre of the world, both the City and the Stock Exchange were hit hard by the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Due to fears that borrowed money was to be called in and that foreign banks would demand their loans or raise interest, prices surged at first. The decision to close the Exchange for improved breathing space and to extend the August Bank Holiday to prohibit a run on banks, was hurried through by the committee and Parliament, respectively. The Stock Exchange ended up being closed from the end of July until the New Year, causing street business to be introduced again, as well as the "challenge system". The Exchange was set to open again on 4 January 1915 under tedious restrictions: transactions were to be in cash only. Due to the limitations and challenges on trading brought by the war, almost a thousand members quit the Exchange between 1914 and 1918. When peace returned in November 1918, the mood on the trading floor was generally cowed. In 1923, the Exchange received its own coat of arms, with the motto Dictum Meum Pactum, My Word is My Bond. Second World WarIn 1937, officials at the Exchange used their experiences from World War I to draw up plans for how to handle a new war. The main concerns included air raids and the subsequent bombing of the Exchange's perimeters, and one suggestion was a move to Denham, Buckinghamshire. This however never took place. On the first day of September 1939, the Exchange closed its doors "until further notice" and two days later World War II was declared. Unlike in the prior war, the Exchange opened its doors again six days later, on 7 September. As the war escalated into its second year, the concerns for air raids were greater than ever. Eventually, on the night of 29 December 1940, one of the greatest fires in London's history took place. The Exchange's floor was hit by a clutch of incendiary bombs, which were extinguished quickly. Trading on the floor was now drastically low and most was done over the phone to reduce the possibility of injuries. The Exchange was only closed for one more day during wartime, in 1945 due to damage from a V-2 rocket. Nonetheless, trading continued in the house's basement. Post-war After decades of uncertain if not turbulent times, stock market business boomed in the late 1950s. This spurred officials to find new, more suitable accommodation. The work on the new Stock Exchange Tower began in 1967. The Exchange's new 321 feet (98 metres) high building had 26 storeys with council and administration at the top, and middle floors let out to affiliate companies. Queen Elizabeth II opened the building on 8 November 1972; it was a new City landmark, with its 23,000 sq ft (2,100 m2) trading floor.  1973 marked a year of changes for the Stock Exchange. First, two trading prohibitions were abolished. A report from the Monopolies and Mergers Commission recommended the admittance of both women and foreign-born members on the floor. Second, in March the London Stock Exchange formally merged with the eleven British and Irish regional exchanges, including the Scottish Stock Exchange.[13] This expansion led to the creation of a new position of Chief Executive Officer; after an extensive search this post was given to Robert Fell. There were more governance changes in 1991, when the governing Council of the Exchange was replaced by a Board of Directors drawn from the Exchange's executive, customer, and user base; and the trading name became "The London Stock Exchange". FTSE 100 Index (pronounced "Footsie 100") was launched by a partnership of the Financial Times and the Stock Exchange on 3 January 1984. This turned out to be one of the most useful indices of all, and tracked the movements of the 100 leading companies listed on the Exchange. IRA bombingOn 20 July 1990, a bomb planted by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) exploded in the men's toilets behind the visitors' gallery. The area had already been evacuated and nobody was injured.[14] About 30 minutes before the blast at 8:49 a.m., a man who said he was a member of the IRA told Reuters that a bomb had been placed at the exchange and was about to explode. Police officials said that if there had been no warning, the human toll would have been very high.[15] The explosion ripped a hole in the 23-storey building in Threadneedle Street and sent a shower of glass and concrete onto the street.[16] The long-term trend towards electronic trading platforms reduced the Exchange's attraction to visitors, and although the gallery reopened, it was closed permanently in 1992. "Big Bang"The biggest event of the 1980s was the sudden de-regulation of the financial markets in the UK in 1986. The phrase "Big Bang" was coined to describe measures, including abolition of fixed commission charges and of the distinction between stockjobbers and stockbrokers on the London Stock Exchange, as well as the change from an open outcry to electronic, screen-based trading. In 1995, the Exchange launched the Alternative Investment Market, the AIM, to allow growing companies to expand into international markets. Two years later, the Electronic Trading Service (SETS) was launched, bringing greater speed and efficiency to the market. Next, the CREST settlement service was launched. In 2000, the Exchange's shareholders voted to become a public limited company, London Stock Exchange plc. London Stock Exchange also transferred its role as UK Listing Authority to the Financial Services Authority (FSA-UKLA). EDX London, an international equity derivatives business, was created in 2003 in partnership with OM Group. The Exchange also acquired Proquote Limited, a new generation supplier of real-time market data and trading systems.   The old Stock Exchange Tower became largely redundant with Big Bang, which deregulated many of the Stock Exchange's activities: computerised systems and dealing rooms replaced face-to-face trading. In 2004, London Stock Exchange moved to a brand-new headquarters in Paternoster Square, close to St Paul's Cathedral. In 2007, the London Stock Exchange merged with Borsa Italiana, creating London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG). The Group's headquarters are in Paternoster Square. The Stock Exchange in Paternoster Square was the initial target for the protesters of Occupy London on 15 October 2011. Attempts to occupy the square were thwarted by police.[17] Police sealed off the entrance to the square as it is private property, a High Court injunction having previously been granted against public access to the square.[18] The protesters moved nearby to occupy the space in front of St Paul's Cathedral.[19] The protests were part of the global Occupy movement. On 25 April 2019, the final day of the Extinction Rebellion disruption in London, 13 activists glued themselves together in a chain, blocking the entrances of the Stock Exchange.[20][21] The protesters were all later arrested on suspicion of aggravated trespass.[21] Extinction Rebellion had said its protesters would target the financial industry "and the corrosive impacts of the ... sector on the world we live in" and activists also blocked entrances to HM Treasury and the Goldman Sachs office on Fleet Street.[22] ActivitiesPrimary marketsThere are two main markets on which companies trade on the LSE: the main market and the alternative investment market. Main MarketThe main market is home to over 1,300 large companies from 60 countries.[23] The FTSE 100 Index ("footsie") is the main share index of the 100 most highly capitalised UK companies listed on the Main Market.[24] Alternative Investment MarketThe Alternative Investment Market is LSE's international market for smaller companies. A wide range of businesses including early-stage, venture capital-backed, as well as more-established companies join AIM seeking access to growth capital. The AIM is classified as a Multilateral Trading Facility (MTF) under the 2004 MiFID directive, and as such it is a flexible market with a simpler admission process for companies wanting to be publicly listed.[25] Secondary marketsThe securities available for trading on London Stock Exchange:[26]

Post tradeThrough the Exchange's Italian arm, Borsa Italiana, the London Stock Exchange Group as a whole offers clearing and settlement services for trades through CC&G (Cassa di Compensazione e Garanzia) and Monte Titoli.[27][28] is the Groups Central Counterparty (CCP) and covers multiple asset classes throughout the Italian equity, derivatives and bond markets. CC&G also clears Turquoise derivatives. Monte Titoli (MT) is the pre-settlement, settlement, custody and asset services provider of the Group. MT operates both on-exchange and OTC trades with over 400 banks and brokers. TechnologyLondon Stock Exchange's trading platform is its own Linux-based edition named Millennium Exchange.[29] Their previous trading platform TradElect was based on Microsoft's .NET Framework, and was developed by Microsoft and Accenture. For Microsoft, LSE was a good combination of a highly visible exchange and yet a relatively modest IT problem.[30] Despite TradElect only being in use for about two years,[31] after suffering multiple periods of extended downtime and unreliability[32][33] the LSE announced in 2009 that it was planning to switch to Linux in 2010.[34][35] The main market migration to MillenniumIT technology was successfully completed in February 2011.[36] LSEG provides high-performance technology, including trading, market surveillance and post-trade systems, for over 40 organisations and exchanges, including the Group's own markets. Additional services include network connectivity, hosting and quality assurance testing. MillenniumIT, GATElab and Exactpro are among the Group's technology companies.[37] The LSE facilitates stock listings in a currency other than its "home currency". Most stocks are quoted in GBP but some are quoted in EUR while others are quoted in USD. Mergers and acquisitionsOn 3 May 2000, it was announced that the LSE would merge with the Deutsche Börse; however this fell through.[38] On 23 June 2007, the London Stock Exchange announced that it had agreed on the terms of a recommended offer to the shareholders of the Borsa Italiana S.p.A. The merger of the two companies created a leading diversified exchange group in Europe. The combined group was named the London Stock Exchange Group, but still remained two separate legal and regulatory entities. One of the long-term strategies of the joint company is to expand Borsa Italiana's efficient clearing services to other European markets. In 2007, after Borsa Italiana announced that it was exercising its call option to acquire full control of MBE Holdings; thus the combined Group would now control Mercato dei Titoli di Stato, or MTS. This merger of Borsa Italiana and MTS with LSE's existing bond-listing business enhanced the range of covered European fixed income markets. London Stock Exchange Group acquired Turquoise (TQ), a Pan-European MTF, in 2009.[39] On 9 October 2020, London Stock Exchange agreed to sell the Borsa Italiana (including Borsa's bond trading platform MTS) to Euronext for €4.3 billion (£3.9 billion) in cash.[40] Euronext completed the acquisition of the Borsa Italiana Group on 29 April 2021 for a final price of €4,444 million.[41] On 12 Dec 2022, Microsoft bought a nearly 4% stake in LSE (London Stock Exchange Group) as part of a ten-year cloud deal.[42] NASDAQ bidsIn December 2005, London Stock Exchange rejected a £1.6 billion takeover offer from Macquarie Bank. London Stock Exchange described the offer as "derisory", a sentiment echoed by shareholders in the Exchange. Shortly after Macquarie withdrew its offer, the LSE received an unsolicited approach from NASDAQ valuing the company at £2.4 billion. This too it rejected. NASDAQ later pulled its bid, and less than two weeks later on 11 April 2006, struck a deal with LSE's largest shareholder, Ameriprise Financial's Threadneedle Asset Management unit, to acquire all of that firm's stake, consisting of 35.4 million shares, at £11.75 per share.[43] NASDAQ also purchased 2.69 million additional shares, resulting in a total stake of 15%. While the seller of those shares was undisclosed, it occurred simultaneously with a sale by Scottish Widows of 2.69 million shares.[44] The move was seen as an effort to force LSE to the negotiating table, as well as to limit the Exchange's strategic flexibility.[45] Subsequent purchases increased NASDAQ's stake to 25.1%, holding off competing bids for several months.[46][47][48] United Kingdom financial rules required that NASDAQ wait for a period of time before renewing its effort. On 20 November 2006, within a month or two of the expiration of this period, NASDAQ increased its stake to 28.75% and launched a hostile offer at the minimum permitted bid of £12.43 per share, which was the highest NASDAQ had paid on the open market for its existing shares.[49] The LSE immediately rejected this bid, stating that it "substantially undervalues" the company.[50] NASDAQ revised its offer (characterized as an "unsolicited" bid, rather than a "hostile takeover attempt") on 12 December 2006, indicating that it would be able to complete the deal with 50% (plus one share) of LSE's stock, rather than the 90% it had been seeking. The U.S. exchange did not, however, raise its bid. Many hedge funds had accumulated large positions within the LSE, and many managers of those funds, as well as Furse, indicated that the bid was still not satisfactory. NASDAQ's bid was made more difficult because it had described its offer as "final", which, under British bidding rules, restricted their ability to raise its offer except under certain circumstances. In the end, NASDAQ's offer was roundly rejected by LSE shareholders. Having received acceptances of only 0.41% of rest of the register by the deadline on 10 February 2007, Nasdaq's offer duly lapsed.[51] On 20 August 2007, NASDAQ announced that it was abandoning its plan to take over the LSE and subsequently look for options to divest its 31% (61.3 million shares) shareholding in the company in light of its failed takeover attempt.[52] In September 2007, NASDAQ agreed to sell the majority of its shares to Borse Dubai, leaving the United Arab Emirates-based exchange with 28% of the LSE.[53] Proposed merger with TMX GroupOn 9 February 2011, London Stock Exchange Group announced it had agreed to merge with the Toronto-based TMX Group, the owners of the Toronto Stock Exchange, creating a combined entity with a market capitalization of listed companies equal to £3.7 trillion.[54] Xavier Rolet, CEO of the LSE Group at the time, would have headed the new enlarged company, while TMX Chief Executive Thomas Kloet would have become the new firm president. London Stock Exchange Group however announced it was terminating the merger with TMX on 29 June 2011 citing that "LSEG and TMX Group believe that the merger is highly unlikely to achieve the required two-thirds majority approval at the TMX Group shareholder meeting".[55] Even though LSEG obtained the necessary support from its shareholders, it failed to obtain the required support from TMX's shareholders. Opening timesNormal trading sessions on the main orderbook (SETS) are from 08:00 to 16:30 local time every day of the week except Saturdays, Sundays and holidays declared by the exchange in advance. The detailed schedule is as follows:

[56] Auction Periods (SETQx) SETSqx (Stock Exchange Electronic Trading Service – quotes and crosses) is a trading service for securities less liquid than those traded on SETS. The auction uncrossings are scheduled to take place at 8:00, 9:00, 11:00, 14:00, and 16:35. Observed holidays are New Year's Day, Good Friday, Easter Monday, May Bank Holiday, Spring Bank Holiday, Summer Bank Holiday, Christmas Day, and Boxing Day. If New Year's Day, Christmas Day, and/or Boxing Day falls on a weekend, the following working day is observed as a holiday. Arms

See also

References

Further reading

External links

[ ⚑ ] 51°30′54.25″N 0°5′56.77″W / 51.5150694°N 0.0991028°W

NYSE: BHP NYSE: BBL ASX: BHP Template:Jse S&P/ASX 200 Component FTSE 100 Component | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Industry | Metals and Mining | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Founded | Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited (BHP) 1885; Billiton plc 1860; Merger of BHP and Billiton, 2001 (creation of a DLC) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Headquarters | Melbourne, Australia (BHP Billiton Limited) London, England (BHP Billiton plc)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Area served | Worldwide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Products | Iron ore, coal, petroleum, copper, natural gas, nickel & uranium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Revenue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total assets | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total equity | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Number of employees | 80,000 (2021)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

BHP, formerly known as BHP Billiton, is the trading entity of BHP Group Limited and BHP Group plc, an Anglo-Australian multinational mining, metals and petroleum dual-listed public company headquartered in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

The Broken Hill Proprietary Company was founded on 16 July 1885 in the mining town of Silverton, New South Wales.[4] By 2017, BHP was the world's largest mining company, based on market capitalisation,[5][6] and was Melbourne's third-largest company by revenue.[7]

BHP Billiton was formed in 2001 through the merger of the Australian Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited (BHP) and the Anglo–Dutch Billiton plc,[8] forming a dual-listed company. The Australia-registered Limited has a primary listing on the Australian Securities Exchange and is one of the largest companies in Australia by market capitalisation. The English-registered plc arm has a primary listing on the London Stock Exchange and is a constituent of the FTSE 100 Index.

In 2015, some BHP Billiton assets were demerged and rebranded as South32, while a scaled-down BHP Billiton became BHP. In 2018, BHP Billiton Limited and BHP Billiton Plc became BHP Group Limited and BHP Group Plc, respectively. In the 2020 Forbes Global 2000, BHP Group was ranked as the 93rd-largest public company in the world.[9]

History

Billiton

Billiton was founded 29 September 1860, when its articles of association were approved by a meeting of shareholders in the Groot Keizershof hotel in The Hague, Netherlands.[10][11] Two months later, the company acquired mineral rights to the Billiton (Belitung) and Bangka Islands in the Netherlands Indies archipelago off the eastern coast of Sumatra.[10][12]

Billiton's initial ventures included tin and lead smelting in the Netherlands, followed in the 1940s by bauxite mining in Indonesia and Suriname.[13] In 1970, Shell acquired Billiton.[10][14] Billiton opened a tin smelting and refining plant in Phuket, Thailand, named Thaisarco (for Thailand Smelting And Refining Company, Limited).[15]

In 1994, South Africa's Gencor acquired the mining division of Billiton excluding the downstream metal division.[16] Billiton was divested from Gencor in 1997,[17] and was amalgamated with Gold Fields in 1998.[18] In 1997, Billiton plc became a constituent of the FTSE 100 Index[19] and in 2001 Billiton plc merged with the Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited (BHP) to form BHP Billiton.[8]

Broken Hill Proprietary Company

The Broken Hill Proprietary Company Limited (BHP), also known by the nickname "the Big Australian",[20] was incorporated on 13 August 1885, operating the silver and lead mine at Broken Hill, in western New South Wales, Australia.[21][22] The Broken Hill group floated on 10 August 1885.[23] The first consignment of Broken Hill ore (48 tons, 5 cwt, 3grs) was smelted at the Intercolonial Smelting and Refining Company's works at Spotswood, Victoria, a suburb of Melbourne.[23] Historian Christopher Jay notes:

The resulting 35,605 ounces of silver raised a lot of interest when exhibited at the City of Melbourne Bank in Collins Street Some sceptics asserted the promoters were merely using silver from somewhere else, to ramp up the shares.... Another shareholder, the dominating W. R. Wilson had had to lend William Jamieson, General Manager, a new suit so he could take the first prospectus, printed at Silverton near Broken Hill on 20 June 1885, to Adelaide to start the float process.[23]

The geographic Broken Hill, for which the town was named, was discovered and named by Captain Charles Sturt, stirring great interest among prospectors. Nothing of note was discovered until 5 November 1883, when Charles Rasp, boundary rider for the surrounding Mount Gipps Station, pegged out a 40-acre claim with contractors David James and James Poole.[24]

Together with a half-dozen backers, including station manager George McCulloch (a young cousin of Victorian Premier Sir James McCulloch),[25] Rasp formed the Broken Hill Company staking out the entire Hill. As costs mounted during the ensuing months of fruitless search, three of the original seven (now remembered as the Syndicate of Seven) sold their shares, so that, on the eve of the company's great success, there were nine shareholders, including Rasp, McCulloch, Philip Charly (aka Charley), David James, James Poole (five of the original syndicate of seven, which had previously included George Urquhart and G.A.M. Lind), Bowes Kelly, W. R. Wilson, and William Jamieson (who'd bought shares from several of the founders).[26][27]

John Darling, Jr. became a director of the company in 1892 and was chairman of directors from 1907 to 1914.[28]

Strongly encouraged by the New South Wales Minister for Public Works, Arthur Hill Griffith,[29][30] in 1915, the company ventured into steel manufacturing, with its operations based primarily in Newcastle, New South Wales. The decision to move from mining ore at Broken Hill to opening a steelworks at Newcastle was due to the technical limitations in recovering value from mining the lower-lying sulphide ores.[31] The discovery of Iron Knob and Iron Monarch near the western shore of the Spencer Gulf in South Australia, combined with the refinement, by BHP metallurgists A. D. Carmichael and Leslie Bradford, of the froth flotation technique for separating zinc sulphides from the accompanying gangue and subsequent conversion (Carmichael–Bradford process) to oxides of the metal, allowed BHP to economically extract valuable metals from the heaps of tailings up to 40 ft (12 m) high at the mine site.[32] In 1942, the Imperial Japanese Navy targeted the BHP steelworks[33] during the largely unsuccessful shelling of Newcastle.[34]

Newcastle operations were closed in 1999,[35] and a 70-ton commemorative sculpture, The Muster Point, was installed on Industrial Drive, in the suburb of Mayfield, New South Wales. The long products side of the steel business was spun off to form OneSteel in 2000.[36]

In the 1950s, BHP began petroleum exploration, which became an increasing focus following oil and natural gas discoveries in Bass Strait in the 1960s.[37][38]

BHP began to diversify into a variety of mining projects overseas. Those included the Ok Tedi copper mine in Papua New Guinea, where the company was successfully sued by the indigenous inhabitants because of the environmental degradation caused by mining operations.[39] BHP had better success with the giant Escondida copper mine in Chile, of which it owns 57.5%, and at the Ekati Diamond Mine in northern Canada, which BHP contracted for in 1996,[40] began mining in 1998,[40] and sold its 80% stake in to Dominion Diamond Corporation in 2013 as production declined.[41][42][43][44]

BHP Billiton

In 2001, BHP merged with the Billiton mining company to form BHP Billiton.[12] In 2002, flat steel products were demerged to form the publicly traded company BHP Steel which, in 2003, became BlueScope Steel.[45]

In March 2005, BHP Billiton announced a US$7.3 billion agreed bid for WMC Resources, owners of the Olympic Dam copper, gold and uranium mine in South Australia, nickel operations in Western Australia and Queensland, and a Queensland fertiliser plant.[46] The takeover achieved 90 per cent acceptance on 17 June 2005, and 100 per cent ownership was announced on 2 August 2005, achieved through compulsory acquisition of the remaining 10 percent of the shares.[47]

On 8 November 2007, BHP Billiton announced it was seeking to purchase rival mining group Rio Tinto Group in an all-share deal.[48] The initial offer of 3.4 shares of BHP Billiton stock for each share of Rio Tinto was rejected by the board of Rio Tinto for "significantly undervaluing" the company.[46] It was unknown at the time whether BHP Billiton would attempt to purchase Rio Tinto through some form of hostile takeover.[46] A formal hostile bid of 3.4 BHP Billiton shares for each Rio Tinto share was announced on 6 February 2008;[49] The bid was withdrawn 25 November 2008 due to global recession.[50][51]

On 14 May 2008, BHP Billiton shares rose to a record high of A$48.90 following speculation that Chinese mining firm Chinalco was considering purchasing a large stake.[52]

As global nickel prices fell, on 25 November 2008, Billiton announced that it would drop its A$66 billion takeover of rival Rio Tinto Group, stating that the "risks to shareholder value" would "increase" to "an unacceptable level" due to the global financial crisis.[53]

On 21 January 2009, BHP Billiton then announced that Ravensthorpe Nickel Mine in Western Australia would cease operations, ending shipments of ore from Ravensthorpe to the Yabulu nickel plant in Queensland Australia.[54] Yabulu refinery was subsequently sold to Queensland billionaire Clive Palmer, becoming the Palmer Nickel and Cobalt Refinery. Pinto Valley mine in the United States was also closed. Mine closures and general scaling back during the global financial crisis accounted for 6,000 employee lay offs.[55]

As the nickel market became saturated by both spiraling economics and cheaper extraction methods; on 9 December 2009, BHP Billiton sold its Ravensthorpe Nickel Mine, which had cost A$2.4 billion to build, to Vancouver -based First Quantum Minerals for US$340 million. First Quantum, a Canadian company, was one of three bidders for the mine, tendering the lowest offer, and returned the mine to production in 2011.[56] Ravensthorpe cost BHP US$3.6 billion in write-downs when it was shut in January 2009 after less than a year of production.[57]

In January 2010, following the BHP Billiton purchase of Athabasca Potash for US$320m, The Economist reported that, by 2020, BHP Billiton could produce approximately 15 per cent of the world demand for potash.[58]

In August 2010, BHP Billiton made a hostile takeover bid worth US$40 billion for PotashCorp. The bid came after BHP's first bid, made on 17 August, was rejected as being undervalued.[59] This acquisition marked a major strategic move by BHP outside hard commodities and commenced the diversification of its business away from resources with high exposure to carbon price risk, like coal, petroleum and iron ore. The takeover bid was opposed by the Government of Saskatchewan under Premier Brad Wall. On 3 November, Canadian Industry Minister Tony Clement announced the preliminary rejection of the deal under the Investment Canada Act, giving BHP Billiton 30 days to refine their deal before a final decision was made;[60] BHP withdrew its offer on 14 November 2010.[61][62]

On 22 February 2011, BHP Billiton announced that it had paid $4.75 billion in cash to Chesapeake Energy for its Fayetteville shale assets, which include 487,000 acres (1,970 km2) of mineral rights leases and 420 miles (680 km) of pipeline located in north central Arkansas. The wells on the mineral leases are currently producing about 415 million cubic feet of natural gas per day. BHP Billiton planned to spend $800 million to $1 billion a year over 10 years to develop the field and triple production.[63]

On 14 July 2011, BHP Billiton announced that it would acquire Petrohawk Energy of the United States for approximately $12.1 billion in cash, considerably expanding its shale natural gas resources[64] in an offer of $US38.75 per share.[65]

On 22 August 2012, BHP Billiton announced that it was delaying its US$20 billion (£12 billion) Olympic Dam copper mine expansion project in South Australia to study less capital intensive options, deferring its dual harbour strategy at West Australian Iron Ore and slowing down its Potash growth option in Canada.[66][67] The company simultaneously announced a freeze on approving any major new expansion projects.[66][67]

Days after announcing the Olympic Dam pull-out, BHP Billiton announced that it was selling its Yeelirrie Uranium Project to Canadian Cameco for a fee of around $430 million. The sale was part of a broader move to step away from resource expansion in Australia.[68]

On 19 August 2014, BHP Billiton announced it would create an independent global metals and mining company based on a selection of its aluminium, coal, manganese, nickel, and silver assets.[69] The newly formed entity, named South32, was subsequently demerged with listings on the Australian Securities Exchange the JSE and the London Stock Exchange.[69]

In 2015, BHP Billiton spun off a number of its subsidiaries[70] in South Africa and Southern Africa to form a new company known as South32.[71][72]

BHP Billiton agreed to pay a fine of $25 million to the United States Securities and Exchange Commission in 2015 in connection with violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act related to its "hospitality program" at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. BHP Billiton invited 176 government and state-owned-enterprise officials to attend the Games on an all-expenses-paid package. While BHP Billiton claimed to have compliance processes in place to avoid conflicts of interest, the SEC found that BHP Billiton had invited officials from at least four countries where BHP Billiton had interests in influencing the officials' decisions (Congo, Guinea, Philippines and Burundi).[73]

In August 2016, BHP Billiton recorded its worst annual loss in history, $6.4 billion.[74]

Towards the end of 2016 BHP Billiton indicated it would expand its petroleum business and make new investments in the sector.[75]

In February 2017, BHP Billiton announced a $2.2 billion investment in the new BP platform in the Gulf of Mexico.[76] During the same year, as part of their plan to increase productivity at the Escondida mine in Chile,[77] which is the world's biggest copper mine, BHP Billiton attempted to get workers to accept a 4-year pay freeze, a 66% reduction in the end-of-conflict bonus offering, and increased shift flexibility. This resulted in a major workers' strike and forced the company to declare force majeure on two shipments, which drove copper prices up by 4%.[78]

In April 2017 activist hedge fund manager Elliott Advisors proposed a plan for BHP Billiton to spin off its American petroleum assets and significantly restructure the business, including the scrapping of its dual Sydney-London listing, suggesting shares be offered only in the United Kingdom, while leaving its headquarters and tax residences in Australia where shares would trade as depository instruments. At the time of the correspondence Elliott held about 4.1 per cent of the issued shares in London-listed BHP Billiton plc, worth $3.81 billion. Australia's government warned it would block moves to shift BHP Billiton's stock listing from Australia to the United Kingdom. Australian Treasurer Scott Morrison said the move would be contrary to the country's national interest and would breach government orders mandating a listing on the Australian Securities Exchange. BHP Billiton dismissed the plan saying the costs and risks of Elliott's proposal outweighed any potential benefits.[79]

BHP

In May 2017, with much of the former Billiton assets having been disposed of, BHP Billiton began to rebrand itself as BHP, at first in Australia and then globally. It replaced the slogan "The Big Australian" with "Think Big", with an advertising campaign rolling out in mid May 2017.[80] Work on the change began in late 2015 according to BHP's chief external affairs officer.[81]

In August 2017, BHP announced that it would sell off its US shale oil and gas business.[82][83] In July 2018, the company agreed to sell its shale assets to BP for $10.5 billion.[84] BHP indicated its intention to return funds to investors.[85] On 29 September 2018, BHP completed the sale of its Fayetteville Onshore US gas assets to a wholly owned subsidiary of Merit Energy Company.[86]

In August 2021, BHP announced plans to exit the oil and gas industry by merging its hydrocarbon business with Woodside Petroleum, Australia’s largest independent gas producer.[87] It also announced its intention to delist from the London Stock Exchange and consolidate on the Australian Securities Exchange.[88]

Corporation

BHP is a dual-listed company; the Australian BHP Billiton Limited and the British BHP Billiton plc are separately listed with separate shareholder bodies, while conducting business as one operation with identical boards of directors and a single management structure.[2] The headquarters of BHP Billiton Limited and the global headquarters of the combined group are located in Melbourne, Australia. The headquarters of BHP Billiton plc are located in London, England.[2] Its main office locations are in Australia, the U.S., Canada, the UK, Chile, Malaysia, and Singapore.[2]

The company's shares trade on the following exchanges:[89]

BHP Billiton Limited and BHP Billiton plc were renamed BHP Group Limited and BHP Group plc, respectively, on 19 November 2018.[90]

London Stock Exchange (LSE) is a stock exchange in the City of London, England , United Kingdom. As of August 2023,[update] the total market value of all companies trading on the LSE stood at $3.18 trillion.[93] Its current premises are situated in Paternoster Square close to St Paul's Cathedral in the City of London. Since 2007, it has been part of the London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG (LSE: [Script error: No such module "Stock tickers/LSE". LSEG])).[94] The LSE is the most-valued stock exchange in Europe as of 2023.[95] According to the 2020 Office for National Statistics report, approximately 12% of UK-resident individuals reported having investments in stocks and shares.[96] According to the 2020 Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) report, approximately 15% of UK adults reported having investments in stocks and shares.[97] HistoryCoffee HouseThe Royal Exchange had been founded by English financier Thomas Gresham and Sir Richard Clough on the model of the Antwerp Bourse. It was opened by Elizabeth I of England in 1571.[98][99] During the 17th century, stockbrokers were not allowed in the Royal Exchange due to their rude manners. They had to operate from other establishments in the vicinity, notably Jonathan's Coffee-House. At that coffee house, a broker named John Castaing started listing the prices of a few commodities, such as salt, coal, paper, and exchange rates in 1698. Originally, this was not a daily list and was only published a few days of the week.[100] This list and activity was later moved to Garraway's coffee house. Public auctions during this period were conducted for the duration that a length of tallow candle could burn; these were known as "by inch of candle" auctions. As stocks grew, with new companies joining to raise capital, the royal court also raised some monies. These are the earliest evidence of organised trading in marketable securities in London. Royal ExchangeAfter Gresham's Royal Exchange building was destroyed in the Great Fire of London, it was rebuilt and re-established in 1669. This was a move away from coffee houses and a step towards the modern model of stock exchange.[101] The Royal Exchange housed not only brokers but also merchants and merchandise. This was the birth of a regulated stock market, which had teething problems in the shape of unlicensed brokers. In order to regulate these, Parliament passed an Act in 1697 that levied heavy penalties, both financial and physical, on those brokering without a licence. It also set a fixed number of brokers (at 100), but this was later increased as the size of the trade grew. This limit led to several problems, one of which was that traders began leaving the Royal Exchange, either by their own decision or through expulsion, and started dealing in the streets of London. The street in which they were now dealing was known as 'Exchange Alley', or 'Change Alley'; it was suitably placed close to the Bank of England. Parliament tried to regulate this and ban the unofficial traders from the Change streets. Traders became weary of "bubbles" when companies rose quickly and fell, so they persuaded Parliament to pass a clause preventing "unchartered" companies from forming. After the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), trade at Jonathan's Coffee House boomed again. In 1773, Jonathan, together with 150 other brokers, formed a club and opened a new and more formal "Stock Exchange" in Sweeting's Alley. This now had a set entrance fee, by which traders could enter the stock room and trade securities. It was, however, not an exclusive location for trading, as trading also occurred in the Rotunda of the Bank of England. Fraud was also rife during these times and in order to deter such dealings, it was suggested that users of the stock room pay an increased fee. This was not met well and ultimately, the solution came in the form of annual fees and turning the Exchange into a Subscription room. The Subscription room created in 1801 was the first regulated exchange in London, but the transformation was not welcomed by all parties. On the first day of trading, non-members had to be expelled by a constable. In spite of the disorder, a new and bigger building was planned, at Capel Court. William Hammond laid the first foundation stone for the new building on 18 May. It was finished on 30 December when "The Stock Exchange" was incised on the entrance. First Rule Book In the Exchange's first operating years, on several occasions there was no clear set of regulations or fundamental laws for the Capel Court trading. In February 1812, the General Purpose Committee confirmed a set of recommendations, which later became the foundation of the first codified rule book of the Exchange. Even though the document was not a complex one, topics such as settlement and default were, in fact, quite comprehensive. With its new governmental commandments[102] and increasing trading volume, the Exchange was progressively becoming an accepted part of the financial life in the city. In spite of continuous criticism from newspapers and the public, the government used the Exchange's organised market (and would most likely not have managed without it) to raise the enormous amount of money required for the wars against Napoleon. Foreign and regional exchangesAfter the war and facing a booming world economy, foreign lending to countries such as Brazil, Peru and Chile was a growing market. Notably, the Foreign Market at the Exchange allowed for merchants and traders to participate, and the Royal Exchange hosted all transactions where foreign parties were involved. The constant increase in overseas business eventually meant that dealing in foreign securities had to be allowed within all of the Exchange's premises. Just as London enjoyed growth through international trade, the rest of Great Britain also benefited from the economic boom. Two other cities, in particular, showed great business development: Liverpool and Manchester. Consequently, in 1836 both the Manchester and Liverpool stock exchanges were opened. Some stock prices sometimes rose by 10%, 20% or even 30% in a week. These were times when stockbroking was considered a real business profession, and such attracted many entrepreneurs. Nevertheless, with booms came busts, and in 1835 the "Spanish panic" hit the markets, followed by a second one two years later. The Exchange before the World Wars By June 1853, both participating members and brokers were taking up so much space that the Exchange was now uncomfortably crowded, and continual expansion plans were taking place. Having already been extended west, east, and northwards, it was then decided the Exchange needed an entire new establishment. Thomas Allason was appointed as the main architect, and in March 1854, the new brick building inspired from the Great Exhibition stood ready. This was a huge improvement in both surroundings and space, with twice the floor space available. By the late 1800s, the telephone, ticker tape, and the telegraph had been invented. Those new technologies led to a revolution in the work of the Exchange. First World War As the financial centre of the world, both the City and the Stock Exchange were hit hard by the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Due to fears that borrowed money was to be called in and that foreign banks would demand their loans or raise interest, prices surged at first. The decision to close the Exchange for improved breathing space and to extend the August Bank Holiday to prohibit a run on banks, was hurried through by the committee and Parliament, respectively. The Stock Exchange ended up being closed from the end of July until the New Year, causing street business to be introduced again, as well as the "challenge system". The Exchange was set to open again on 4 January 1915 under tedious restrictions: transactions were to be in cash only. Due to the limitations and challenges on trading brought by the war, almost a thousand members quit the Exchange between 1914 and 1918. When peace returned in November 1918, the mood on the trading floor was generally cowed. In 1923, the Exchange received its own coat of arms, with the motto Dictum Meum Pactum, My Word is My Bond. Second World WarIn 1937, officials at the Exchange used their experiences from World War I to draw up plans for how to handle a new war. The main concerns included air raids and the subsequent bombing of the Exchange's perimeters, and one suggestion was a move to Denham, Buckinghamshire. This however never took place. On the first day of September 1939, the Exchange closed its doors "until further notice" and two days later World War II was declared. Unlike in the prior war, the Exchange opened its doors again six days later, on 7 September. As the war escalated into its second year, the concerns for air raids were greater than ever. Eventually, on the night of 29 December 1940, one of the greatest fires in London's history took place. The Exchange's floor was hit by a clutch of incendiary bombs, which were extinguished quickly. Trading on the floor was now drastically low and most was done over the phone to reduce the possibility of injuries. The Exchange was only closed for one more day during wartime, in 1945 due to damage from a V-2 rocket. Nonetheless, trading continued in the house's basement. Post-war After decades of uncertain if not turbulent times, stock market business boomed in the late 1950s. This spurred officials to find new, more suitable accommodation. The work on the new Stock Exchange Tower began in 1967. The Exchange's new 321 feet (98 metres) high building had 26 storeys with council and administration at the top, and middle floors let out to affiliate companies. Queen Elizabeth II opened the building on 8 November 1972; it was a new City landmark, with its 23,000 sq ft (2,100 m2) trading floor.  1973 marked a year of changes for the Stock Exchange. First, two trading prohibitions were abolished. A report from the Monopolies and Mergers Commission recommended the admittance of both women and foreign-born members on the floor. Second, in March the London Stock Exchange formally merged with the eleven British and Irish regional exchanges, including the Scottish Stock Exchange.[103] This expansion led to the creation of a new position of Chief Executive Officer; after an extensive search this post was given to Robert Fell. There were more governance changes in 1991, when the governing Council of the Exchange was replaced by a Board of Directors drawn from the Exchange's executive, customer, and user base; and the trading name became "The London Stock Exchange". FTSE 100 Index (pronounced "Footsie 100") was launched by a partnership of the Financial Times and the Stock Exchange on 3 January 1984. This turned out to be one of the most useful indices of all, and tracked the movements of the 100 leading companies listed on the Exchange. IRA bombingOn 20 July 1990, a bomb planted by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) exploded in the men's toilets behind the visitors' gallery. The area had already been evacuated and nobody was injured.[104] About 30 minutes before the blast at 8:49 a.m., a man who said he was a member of the IRA told Reuters that a bomb had been placed at the exchange and was about to explode. Police officials said that if there had been no warning, the human toll would have been very high.[105] The explosion ripped a hole in the 23-storey building in Threadneedle Street and sent a shower of glass and concrete onto the street.[106] The long-term trend towards electronic trading platforms reduced the Exchange's attraction to visitors, and although the gallery reopened, it was closed permanently in 1992. "Big Bang"The biggest event of the 1980s was the sudden de-regulation of the financial markets in the UK in 1986. The phrase "Big Bang" was coined to describe measures, including abolition of fixed commission charges and of the distinction between stockjobbers and stockbrokers on the London Stock Exchange, as well as the change from an open outcry to electronic, screen-based trading. In 1995, the Exchange launched the Alternative Investment Market, the AIM, to allow growing companies to expand into international markets. Two years later, the Electronic Trading Service (SETS) was launched, bringing greater speed and efficiency to the market. Next, the CREST settlement service was launched. In 2000, the Exchange's shareholders voted to become a public limited company, London Stock Exchange plc. London Stock Exchange also transferred its role as UK Listing Authority to the Financial Services Authority (FSA-UKLA). EDX London, an international equity derivatives business, was created in 2003 in partnership with OM Group. The Exchange also acquired Proquote Limited, a new generation supplier of real-time market data and trading systems.   The old Stock Exchange Tower became largely redundant with Big Bang, which deregulated many of the Stock Exchange's activities: computerised systems and dealing rooms replaced face-to-face trading. In 2004, London Stock Exchange moved to a brand-new headquarters in Paternoster Square, close to St Paul's Cathedral. In 2007, the London Stock Exchange merged with Borsa Italiana, creating London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG). The Group's headquarters are in Paternoster Square. The Stock Exchange in Paternoster Square was the initial target for the protesters of Occupy London on 15 October 2011. Attempts to occupy the square were thwarted by police.[107] Police sealed off the entrance to the square as it is private property, a High Court injunction having previously been granted against public access to the square.[108] The protesters moved nearby to occupy the space in front of St Paul's Cathedral.[109] The protests were part of the global Occupy movement. On 25 April 2019, the final day of the Extinction Rebellion disruption in London, 13 activists glued themselves together in a chain, blocking the entrances of the Stock Exchange.[110][111] The protesters were all later arrested on suspicion of aggravated trespass.[111] Extinction Rebellion had said its protesters would target the financial industry "and the corrosive impacts of the ... sector on the world we live in" and activists also blocked entrances to HM Treasury and the Goldman Sachs office on Fleet Street.[112] ActivitiesPrimary marketsThere are two main markets on which companies trade on the LSE: the main market and the alternative investment market. Main MarketThe main market is home to over 1,300 large companies from 60 countries.[113] The FTSE 100 Index ("footsie") is the main share index of the 100 most highly capitalised UK companies listed on the Main Market.[114] Alternative Investment MarketThe Alternative Investment Market is LSE's international market for smaller companies. A wide range of businesses including early-stage, venture capital-backed, as well as more-established companies join AIM seeking access to growth capital. The AIM is classified as a Multilateral Trading Facility (MTF) under the 2004 MiFID directive, and as such it is a flexible market with a simpler admission process for companies wanting to be publicly listed.[115] Secondary marketsThe securities available for trading on London Stock Exchange:[116]

Post tradeThrough the Exchange's Italian arm, Borsa Italiana, the London Stock Exchange Group as a whole offers clearing and settlement services for trades through CC&G (Cassa di Compensazione e Garanzia) and Monte Titoli.[117][118] is the Groups Central Counterparty (CCP) and covers multiple asset classes throughout the Italian equity, derivatives and bond markets. CC&G also clears Turquoise derivatives. Monte Titoli (MT) is the pre-settlement, settlement, custody and asset services provider of the Group. MT operates both on-exchange and OTC trades with over 400 banks and brokers. TechnologyLondon Stock Exchange's trading platform is its own Linux-based edition named Millennium Exchange.[119] Their previous trading platform TradElect was based on Microsoft's .NET Framework, and was developed by Microsoft and Accenture. For Microsoft, LSE was a good combination of a highly visible exchange and yet a relatively modest IT problem.[120] Despite TradElect only being in use for about two years,[121] after suffering multiple periods of extended downtime and unreliability[122][123] the LSE announced in 2009 that it was planning to switch to Linux in 2010.[124][125] The main market migration to MillenniumIT technology was successfully completed in February 2011.[126] LSEG provides high-performance technology, including trading, market surveillance and post-trade systems, for over 40 organisations and exchanges, including the Group's own markets. Additional services include network connectivity, hosting and quality assurance testing. MillenniumIT, GATElab and Exactpro are among the Group's technology companies.[127] The LSE facilitates stock listings in a currency other than its "home currency". Most stocks are quoted in GBP but some are quoted in EUR while others are quoted in USD. Mergers and acquisitionsOn 3 May 2000, it was announced that the LSE would merge with the Deutsche Börse; however this fell through.[128] On 23 June 2007, the London Stock Exchange announced that it had agreed on the terms of a recommended offer to the shareholders of the Borsa Italiana S.p.A. The merger of the two companies created a leading diversified exchange group in Europe. The combined group was named the London Stock Exchange Group, but still remained two separate legal and regulatory entities. One of the long-term strategies of the joint company is to expand Borsa Italiana's efficient clearing services to other European markets. In 2007, after Borsa Italiana announced that it was exercising its call option to acquire full control of MBE Holdings; thus the combined Group would now control Mercato dei Titoli di Stato, or MTS. This merger of Borsa Italiana and MTS with LSE's existing bond-listing business enhanced the range of covered European fixed income markets. London Stock Exchange Group acquired Turquoise (TQ), a Pan-European MTF, in 2009.[129] On 9 October 2020, London Stock Exchange agreed to sell the Borsa Italiana (including Borsa's bond trading platform MTS) to Euronext for €4.3 billion (£3.9 billion) in cash.[130] Euronext completed the acquisition of the Borsa Italiana Group on 29 April 2021 for a final price of €4,444 million.[131] On 12 Dec 2022, Microsoft bought a nearly 4% stake in LSE (London Stock Exchange Group) as part of a ten-year cloud deal.[132] NASDAQ bidsIn December 2005, London Stock Exchange rejected a £1.6 billion takeover offer from Macquarie Bank. London Stock Exchange described the offer as "derisory", a sentiment echoed by shareholders in the Exchange. Shortly after Macquarie withdrew its offer, the LSE received an unsolicited approach from NASDAQ valuing the company at £2.4 billion. This too it rejected. NASDAQ later pulled its bid, and less than two weeks later on 11 April 2006, struck a deal with LSE's largest shareholder, Ameriprise Financial's Threadneedle Asset Management unit, to acquire all of that firm's stake, consisting of 35.4 million shares, at £11.75 per share.[133] NASDAQ also purchased 2.69 million additional shares, resulting in a total stake of 15%. While the seller of those shares was undisclosed, it occurred simultaneously with a sale by Scottish Widows of 2.69 million shares.[134] The move was seen as an effort to force LSE to the negotiating table, as well as to limit the Exchange's strategic flexibility.[135] Subsequent purchases increased NASDAQ's stake to 25.1%, holding off competing bids for several months.[136][137][138] United Kingdom financial rules required that NASDAQ wait for a period of time before renewing its effort. On 20 November 2006, within a month or two of the expiration of this period, NASDAQ increased its stake to 28.75% and launched a hostile offer at the minimum permitted bid of £12.43 per share, which was the highest NASDAQ had paid on the open market for its existing shares.[139] The LSE immediately rejected this bid, stating that it "substantially undervalues" the company.[140] NASDAQ revised its offer (characterized as an "unsolicited" bid, rather than a "hostile takeover attempt") on 12 December 2006, indicating that it would be able to complete the deal with 50% (plus one share) of LSE's stock, rather than the 90% it had been seeking. The U.S. exchange did not, however, raise its bid. Many hedge funds had accumulated large positions within the LSE, and many managers of those funds, as well as Furse, indicated that the bid was still not satisfactory. NASDAQ's bid was made more difficult because it had described its offer as "final", which, under British bidding rules, restricted their ability to raise its offer except under certain circumstances. In the end, NASDAQ's offer was roundly rejected by LSE shareholders. Having received acceptances of only 0.41% of rest of the register by the deadline on 10 February 2007, Nasdaq's offer duly lapsed.[141] On 20 August 2007, NASDAQ announced that it was abandoning its plan to take over the LSE and subsequently look for options to divest its 31% (61.3 million shares) shareholding in the company in light of its failed takeover attempt.[142] In September 2007, NASDAQ agreed to sell the majority of its shares to Borse Dubai, leaving the United Arab Emirates-based exchange with 28% of the LSE.[143] Proposed merger with TMX GroupOn 9 February 2011, London Stock Exchange Group announced it had agreed to merge with the Toronto-based TMX Group, the owners of the Toronto Stock Exchange, creating a combined entity with a market capitalization of listed companies equal to £3.7 trillion.[144] Xavier Rolet, CEO of the LSE Group at the time, would have headed the new enlarged company, while TMX Chief Executive Thomas Kloet would have become the new firm president. London Stock Exchange Group however announced it was terminating the merger with TMX on 29 June 2011 citing that "LSEG and TMX Group believe that the merger is highly unlikely to achieve the required two-thirds majority approval at the TMX Group shareholder meeting".[145] Even though LSEG obtained the necessary support from its shareholders, it failed to obtain the required support from TMX's shareholders. Opening timesNormal trading sessions on the main orderbook (SETS) are from 08:00 to 16:30 local time every day of the week except Saturdays, Sundays and holidays declared by the exchange in advance. The detailed schedule is as follows:

[146] Auction Periods (SETQx) SETSqx (Stock Exchange Electronic Trading Service – quotes and crosses) is a trading service for securities less liquid than those traded on SETS. The auction uncrossings are scheduled to take place at 8:00, 9:00, 11:00, 14:00, and 16:35. Observed holidays are New Year's Day, Good Friday, Easter Monday, May Bank Holiday, Spring Bank Holiday, Summer Bank Holiday, Christmas Day, and Boxing Day. If New Year's Day, Christmas Day, and/or Boxing Day falls on a weekend, the following working day is observed as a holiday. Arms

See also

References

Further reading

External links

[ ⚑ ] 51°30′54.25″N 0°5′56.77″W / 51.5150694°N 0.0991028°W

)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Senior management

In 1998, BHP hired American Paul Anderson to restructure the company. Anderson successfully completed the four-year project with a merger between BHP and London-based Billiton.[1] In July 2002, Brian Gilbertson of Billiton was appointed CEO, but resigned after just six months, citing irreconcilable differences with the board.[2]

Upon Gilbertson's departure in early 2003, Chip Goodyear was appointed the new CEO, increasing sales by 47 percent and profits by 78 percent during his tenure.[3] Goodyear retired on 30 September 2007.[4] Marius Kloppers was Goodyear's successor.[4] Following Kloppers' tenure, Andrew Mackenzie, chief executive of Non-Ferrous, assumed the role of CEO in 2013.[5] Australia mining head Mike Henry succeeded Mackenzie on 1 January 2020.[6]

Operations

BHP has mining operations in Australia, North America, and South America, and petroleum operations in the U.S., Australia, Trinidad and Tobago, the UK, and Algeria.[7]

The company has four primary operational units:

The company's mines are as follows:[8]

Algeria

- Ohanet gas field

- ROD gas field

Australia

New South Wales

- Mount Arthur Coal mine

Queensland

- Blackwater Mine (50%) BHP Mitsubishi Alliance

- Broadmeadow (50%) BHP Mitsubishi Alliance

- Goonyella (50%) BHP Mitsubishi Alliance

- Hay Point

- Peak Downs (50%) BHP Mitsubishi Alliance

- Poitrel Metallurgical Coal Mine (Jointly owned with Mitsui)

- Saraji (50%) BHP Mitsubishi Alliance

South Australia

- Olympic Dam

Victoria

- Bass Strait (50%)

- Minerva offshore (90%)

Western Australia

- Area C mine

- Eastern Range mine

- Jimblebar mine

- Kalgoorlie

- Kambalda

- Kwinana

- Leinster

- Mount Keith

- Mount Whaleback

- Nickel West operations

- Nimingarra Iron Ore Mine, Jointly owned with Itochu and Mitsubishi)

- North West Shelf Venture, (16.67% LNG phase, 8.33% domestic gas phase.)

- Orebodies 18, 23 and 25 mine

- Port Hedland

- Yandi mine

- Yarrie mine

Brazil

- Samarco: a joint-venture with Vale (50% ownership each). The project led to the worst environmental disaster in the history of mining in Brazil:[9] the collapse of two iron ore tailings dams[10] in Bento Rodrigues, a subdistrict of Mariana.

Canada

- Jansen potash development project, Saskatchewan

Chile

- Minera Escondida Copper, gold and silver mine jointly owned with Rio Tinto Group and Pan Pacific Copper

- Cerro Colorado

- Spence

Colombia

- Cerrejón coal mine in Guajira department (33.3%)

Mexico

- Trion

Peru

- Antamina

Trinidad & Tobago

- Angostura & Ruby oil and gas fields

United States

- Gulf of Mexico, oil and gas field (Shenzi field)

- Resolution Copper, near Superior, Arizona

Responsibility for climate damage

BHP is listed as one of the 90 fossil fuel extraction and marketing companies responsible for two-thirds of global greenhouse gas emissions since the beginning of the industrial age.[11] Its cumulative emissions as of 2010 have been estimated at 7,606 MtCO

2e, representing 0.52% of global industrial emissions between 1751 and 2010, ranking it the 19th-largest corporate polluter.[12] According to BHP management 10% of these emissions are from direct operations, while 90% come from products sold by the company.[13] BHP has been voluntarily reporting its direct GHG emissions since 1996. In 2013, it was criticised for lobbying against carbon pricing in Australia.[14]

BHP reported total CO2e emissions (Direct + Indirect) for the twelve months ending 30 June 2020 at 15,800 Kt.[15]

| Jun 2015 | Jun 2016 | Jun 2017 | Jun 2018 | Jun 2019 | Jun 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38,300[16] | 18,000[17] | 16,300[18] | 17,000[19] | 15,800[20] | 15,800[15] |

Significant accidents

Bad weather caused a BHP Billiton helicopter to crash in Angola on 16 November 2007, killing the helicopter's five passengers. The deceased were: BHP Billiton Angola Chief Operating Officer David Hopgood (Australian), Angola Technical Services Operations Manager Kevin Ayre (British), Wild Dog Helicopters pilot Kottie Breedt (South African), Guy Sommerfield (British) of MMC and Louwrens Prinsloo (Namibian) of Prinsloo Drilling. The helicopter crashed approximately 80 kilometres (50 mi) from the Alto Cuilo diamond exploration camp in Lunda Norte, northeastern Angola. BHP Billiton responded by suspending operations in the country.[21]

In 2015, the company was involved in the Bento Rodrigues tailings dam collapse, the worst environmental disaster in the history of the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil.[9][10][22] On 5 November 2015, an iron ore mine tailings dam near Mariana, south-eastern Brazil, owned and operated by Samarco, a subsidiary of BHP and Vale,[23] suffered a catastrophic failure, devastating the nearby town of Bento Rodrigues with the mudflow, killing 19 people, injuring more than 50 and causing enormous ecological damage,[24] and threatening life along the Rio Doce and the Atlantic Ocean near the mouth of the Rio Doce.[25] The accident was one of the biggest environmental disasters in Brazil's history.[26]

See also

- Mining in Australia

References

- ↑ Parkinson, Gary (2001-03-19). "Billiton and BHP agree merger plans" (in en-GB). Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/4486005/Billiton-and-BHP-agree-merger-plans.html.

- ↑ "BHP chief in shock resignation". CNN. 5 January 2003. http://edition.cnn.com/2003/BUSINESS/asia/01/05/australia.BHP.biz/index.html.

- ↑ "The Best European Performers". Business Week. 18 June 2005. http://www.mediaset.it/gruppomediaset/bin/45.$plit/bus_week_18_06_05_mediaset.pdf.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "BHP Billiton To Appoint Marius Kloppers As New CEO" (press release). 31 May 2007. https://www.bhp.com/media-and-insights/news-releases/2007/05/bhp-billiton-to-appoint-marius-kloppers-as-new-ceo.

- ↑ "Mackenzie, Andrew Stewart". Who's Who. 2014 (online edition via Oxford University Press ed.). A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc. https://www.ukwhoswho.com/view/article/oupww/whoswho/U257762. (subscription or UK public library membership required) (Subscription content?)

- ↑ "Mike Henry's 30-year journey to BHP's top job"; James Thompson; The Australian Financial Review; Nov. 14, 2019.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedar - ↑ "BHP Billiton". https://mining-atlas.com/company/BHP-Billiton.php.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Rezende, Felipe (6 November 2015). "Rompimento de barragens causa "maior dano ambiental da história de Minas", diz promotor" (in pt). R7. https://noticias.r7.com/minas-gerais/rompimento-de-barragens-causa-maior-dano-ambiental-da-historia-de-minas-diz-promotor-06112015.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Darlington, Shasta (7 November 2015). "Dam break sweeps away homes in Brazil, killing at least 1 person". CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2015/11/06/americas/brazil-dam-break-flooding/index.html.

- ↑ Goldenberg, Suzanne (21 November 2013). "Just 90 companies caused two-thirds of man-made global warming emissions". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/nov/20/90-companies-man-made-global-warming-emissions-climate-change.

- ↑ Heede, Richard (January 2014). "Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854–2010". Climate Change 122 (1–2): 229–241. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0986-y. Bibcode: 2014ClCh..122..229H.

- ↑ Hannam, Peter (21 November 2013). "BHP among world's 20 largest climate culprits". The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/business/the-economy/bhp-among-worlds-20-largest-climate-culprits-20131121-2xxtt.html.

- ↑ Mehra, Malini (20 November 2013). "BHP Billiton: climate change leader or laggard?". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/blog/bhp-billiton-climate-change-leader-laggard.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "BHP's Annual Report for 2020Q2". https://www.bhp.com/-/media/documents/investors/annual-reports/2020/200915_bhpannualreport2020.pdf?la=en.

- ↑ "BHP's Annual Report for 2017Q2". https://www.bhp.com/investor-centre/annual-report-2018/-/media/documents/investors/annual-reports/2017/bhpannualreport2017.pdf.

- ↑ "BHP's Annual Report for 2018Q2". https://www.bhp.com/-/media/documents/investors/annual-reports/2018/bhpannualreport2018.pdf.

- ↑ "BHP's Annual Report for 2020Q2". https://www.bhp.com/-/media/documents/investors/annual-reports/2020/200915_bhpannualreport2020.pdf?la=en.

- ↑ "BHP's Annual Report for 2020Q2". https://www.bhp.com/-/media/documents/investors/annual-reports/2020/200915_bhpannualreport2020.pdf?la=en.

- ↑ "BHP's Annual Report for 2020Q2". https://www.bhp.com/-/media/documents/investors/annual-reports/2020/200915_bhpannualreport2020.pdf?la=en.

- ↑ "Fatal Helicopter Crash in Angola". 17 November 2007. https://www.bhp.com/media-and-insights/news-releases/2007/11/fatal-helicopter-crash-in-angola.

- ↑ "Brazil dam burst: at least 15 feared dead after disaster at BHP-owned mine". The Guardian. 6 November 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/nov/05/brazil-iron-mine-dam-bursts-floods-nearby-homes.

- ↑ Safari, Maryam; Bicudo, de Castro Vincent; Steccolini, Ileana (2020-01-01). "The interplay between home and host logics of accountability in multinational corporations (MNCs): the case of the Fundão dam disaster". Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print): 1761–1789. doi:10.1108/AAAJ-03-2019-3912. ISSN 0951-3574. http://repository.essex.ac.uk/30403/1/Samarco%20pdf%20for%20open%20access.pdf.

- ↑ Timson, Lia; de Godo, Lucas (3 November 2018). "Putting Bento Rodrigues back on the map after the dam disaster". The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/world/south-america/putting-bento-rodrigues-back-on-the-map-after-the-dam-disaster-20181102-p50dki.html.

- ↑ Douglas, Bruce (22 November 2015). "Anger rises as Brazilian mine disaster threatens river and sea with toxic mud". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/nov/22/anger-rises-as-brazilian-mine-disaster-threatens-river-and-sea-with-toxic-mud.

- ↑ Santos, Caio (16 November 2016). "Entre o luto e a saudade: um panorama do maior desastre ambiental do Brasil". https://jornalistaslivres.org/entre-o-luto-e-a-saudade-um-panorama-do-maior-desastre-ambiental-do-brasil/.

External links

- Business data for BHP:

- Documents and clippings about BHP in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW