Earth:Agrio Formation

| Agrio Formation Stratigraphic range: Late Valanginian-earliest Aptian ~130–120 Ma | |

|---|---|

Agrio Formation at its type section | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Mendoza Group |

| Sub-units | Pilmatué, Avilé & Agua de la Mula Members |

| Underlies | Huitrín & La Amarga Formations |

| Overlies | Mulichinco & Bajada Colorada Formations |

| Area | 220 km × 50 km (137 mi × 31 mi) |

| Thickness | Up to 1,500 m (4,900 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Shale, sandstone |

| Other | Limestone, conglomerate |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 38°00′S 70°00′W / 38.0°S 70.0°W |

| Paleocoordinates | [ ⚑ ] 38°12′S 33°42′W / 38.2°S 33.7°W |

| Region | Mendoza & Neuquén Provinces |

| Country | Argentina |

| Extent | Neuquén Basin |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Agrio River |

| Named by | Weaver |

| Year defined | 1931 |

The Agrio Formation is an Early Cretaceous geologic formation that is up to 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) thick and is located in the southern Mendoza Province and northern-central Neuquén Province, in the Neuquén Basin of northwestern Patagonia, Argentina .[1] This formation is the youngest one of the Mendoza Group, overlying the Mulichinco and Bajada Colorada Formations and overlain by the Huitrín and La Amarga Formations. It is dated to the Late Valanginian to Early Hauterivian,[2] Late Valanginian to Early Barremian,[3] or Hauterivian to earliest Aptian.[4]

The Agrio Formation is considered the third most important source rock in the hydrocarbon-rich Neuquén Basin, after the Vaca Muerta Formation and Los Molles Formation. Similarly to these older units, it is potentially a source of shale gas.

This formation has provided fossils of ichthyosaurs, ammonites, gastropods, bivalves, decapods, echinoderm, corals and fish. The newly described species of fish, Tranawuen agrioensis, the ammonite Holcoptychites agrioensis, and the bivalve Pholadomya agrioensis have been named after the formation.

Description

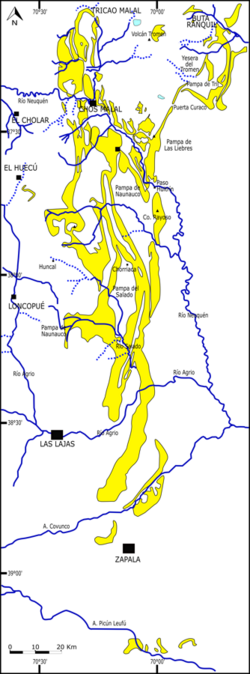

The Agrio Formation was first described by Weaver in 1931 and its three members, from bottom to top: Pilmatué, Avilé and Agua de la Mula Members, were defined by Leanza and Hugo in 2001.[5][1][3] The formation crops out in an approximately 50 kilometres (31 mi) wide band from north to south along 70° longitude west, from 37° to 39° south in the northern-central part of the Neuquén Basin.[6] The southern termination of the formation is the Huincul High, formed by the Huincul Fault. Towards the east in the basin, the formation grades into the Centenario Formation.[3]

Stratigraphy

The Agrio Formation is included in the Mendoza Group, representing its youngest formation. In the east of the Neuquén Basin, the formation rests upon continental clastic deposits of the Mulichinco Formation, with the contact between the two formations characterized by a regional transgressive surface. Towards the west, the formation unconformably overlies the Bajada Colorada Formation.[7][8][9] In its eastern part, the Agrio Formation is overlain by the clastic, carbonaceous and evaporitic deposits of the Huitrín Formation and in the western area by the La Amarga Formation. The total thickness of the Agrio Formation reaches up to 1,500 metres (4,900 ft), with the Pilmatué Member having a thickness of 718 metres (2,356 ft) and the Agua de la Mula Member reaching 501 metres (1,644 ft).[10]

Lithologies

The Agrio Formation is primarily composed of pelitic rocks with intercalations of limestones, sandstones and rare fine conglomerates. The Pilmatué and Agua de la Mula Members are characterized by thick successions of black shales with intercalating limestones and sandstones. The Avilé Member comprises sandstones and claystones with conglomerates.[11][10]

Depositional environment

The Agrio Formation was deposited in a post-rift setting of the Neuquén Basin, probably representing a tectonic regime of thermal subsidence. The sediments of the lower and upper members of the formation are marine in character, interpreted as the combination of thermal subsidence and a eustatic sea level rise.[12][13][6] The middle Avilé member was deposited in a fluvial environment. Within the marine Pilmatué Member, a succession of approximately 130 metres (430 ft) thick, described as "San Eduardo Beds", is recognized as deposited in a wave-dominated deltaic setting with hyperdense currents. This sequence is overlain by about 40 metres (130 ft) thick limestones deposits in a reefal environment.[10] The presence of the newly described gastropod Eunerinea mendozana led researchers to estimate tropical conditions for the Agrio Formation.[14]

Fossil content

The formation has provided many fossils of ammonites,[15] gastropods, bivalves, corals, decapods, echinoids, crinoids and nano and microfossils (calcareous nannofossils, ostracods, foraminifers).[5][16][17][18][19][20]

In 2018, ichthyosaur remains not determined to the genus level were described from the Agrio Formation, suggesting the possibility of viviparity of these marine reptiles in the epeiric sea of the Neuquén Basin. The finds were notable as well because of a relative lack of abundance of ichthyosaur fossils from the Valanginian to Hauterivian worldwide.[21] Fossil fish of Gyrodus huiliches, and Tranawuen agrioensis were described from the formation in 2019.[22]

The decapod Palaeohomarus pacificus,[23] and ammonites Curacoites rotundus and Sabaudiella riverorum were described from the formation in 2012,[24] the gastropods Ampullina pichinka and Mesalia? kushea in 2016,[25] and the ammonite Comahueites aequalicostatus in 2018.[26]

Newly described species of fish, Tranawuen agrioensis,[22] ammonite, Holcoptychites agrioensis,[27] and the bivalve Pholadomya agrioensis were named after the formation.[16]

The first known brittle stars in the Southern Hemisphere and Cretaceous age have been identified in Agrio Formation.[28] However, fossils are not complete enough to define species.[28]

Petroleum geology

The Agrio Formation is considered the third-most important source rock of the hydrocarbon-rich Neuquén Basin, after the older Vaca Muerta and Los Molles Formations.[29] Two levels of organic-rich sediments exist in the formation, related to the marine transgressions of the late Valanginian and the late Hauterivian, in the Pilmatué and Agua de la Mula Members respectively. The marly shales of the Pilmatué Member reach up to 400 metres (1,300 ft) thickness in the western Neuquén Basin, while the same facies in the Agua de la Piedra Member is less than 100 metres (330 ft) thick. The organic properties of the formation are similar to the Vaca Muerta, with a TOC value averaging 2.5%, with some levels up to 5%. The kerogen types are II to II/III.[2]

Gallery

-

Ammonite from the Agrio Formation

-

Bivalve from the formation

-

Bivalve (Ptychomya koeneni)

See also

- List of dinosaur-bearing rock formations

- Caiuá Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of the Paraná Basin

- Cerro Barcino Formation, contemporaneous fossiliferous formation of the Cañadón Asfalto Basin

- Zapata and Río Belgrano Formations, contemporaneous fossiliferous formations of the Magallanes or Austral Basin

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weaver, C. E. (1931). Paleontology of the Jurassic and cretaceous of west central Argentina. In Memoires of the University of Washington (Vol. 1, pp. 1–599).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Voglino, 2017, p.39

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Voglino, 2017, p.49

- ↑ Gómez Dacal et al., 2018, p.113

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Archuby, F. M. (2009). Taphonomy and palaeoecology of benthic macroinvertebrates from the Agua de la Mula Member of the Agrio Formation, Neuquén Basin (Neuquén province, Argentina): sequence stratigraphic significance [Würzburg University]. http://www.opus-bayern.de/uni-wuerzburg/volltexte/2009/3717/index.html

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Voglino, 2017, p.50

- ↑ Leanza, H. A., Hugo, C. A., & Repol, D. (2001). Hoja Geológica 3969-I, Zapala. Provincia del Neuquén. In Referencia bibliográfica LEANZA, H.A., C. A. HUGO y D. REPOL, 2001. Hoja Geológica 3969-I, Zapala. Provincia del Neuquén. Instituto de Geología y Recursos Minerales, Servicio Geoló- gico Minero Argentino. Boletín (Vol. 275).

- ↑ Olivo et al., 2016, p.218

- ↑ Gallina et al., 2014, p.2

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Voglino, 2017, p.51

- ↑ Archuby, F. M., & Fürsich, F. T. (2010). Facies analysis of a higly [sic?] cyclic sedimentary unit: the Late Hauterivian to Early Barremian Agua de la Mula Member of the Agrio Formation, Neuquén Basin, Argentina. Beringeria, 41, 53–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v56i3.27147

- ↑ Archuby, F. M., Wilmsen, M., & Leanza, H. A. (2011). Integrated stratigraphy of the Upper Hauterivian to Lower Barremian Agua de la Mula Member of the Agrio Formation, Neuquén Basin, Argentina. Acta Geologica Polonica, 61(1), 1–26.

- ↑ Archuby, F. M., & Fürsich, F. T. (2010). Facies analysis of a higly cyclic sedimentary unit: the Late Hauterivian to Early Barremian Agua de la Mula Member of the Agrio Formation, Neuquén Basin, Argentina. Beringeria, 41, 53–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15517/rbt.v56i3.27147

- ↑ Cataldo, 2012

- ↑ Aguirre Urreta, 1998

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Kauffman & Leanza, 2004

- ↑ Agrio Formation at Fossilworks.org

- ↑ Ballent, S., Concheyro, A., Náñez, C., Pujana, I., Lescano, M., Carignano, A. P., Caramés, A., Angelozzi, G., & Ronchi, D. (2011). Microfósiles Mesozoicos Y Cenozoicos. Relatorio Del XVIII Congreso Geológico Argentino, September 2017, 489–528.

- ↑ Ballent, Sara; Concheyro, Andrea; Sagasti, Guillermina (January 2006). "Bioestratigrafía y paleoambiente de la Formación Agrio (Cretácico Inferior), en la Provincia de Mendoza, Cuenca Neuquina, Argentina". Revista Geológica de Chile 33 (1): 47–79. doi:10.4067/S0716-02082006000100003. ISSN 0716-0208. https://scielo.conicyt.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S0716-02082006000100003&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en.

- ↑ Caratelli, Martina; Archuby, Fernando M.; Fürsich, Franz; Pignatti, Johannes (2021-07-01). "Macroids from mixed siliciclastic-carbonate high-frequency sequences of the Agrio Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Neuquén Basin: Palaeoecological and palaeoenvironmental constraints" (in en). Cretaceous Research 123: 104778. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104778. ISSN 0195-6671. Bibcode: 2021CrRes.12304778C. http://rid.unrn.edu.ar/bitstream/20.500.12049/9510/3/Caratelli.pdf.

- ↑ Lazo et al., 2018

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Gouiric Cavalli et al., 2019

- ↑ Aguirre Urreta et al., 2012

- ↑ Aguirre Urreta & Rawson, 2012

- ↑ Cataldo & Lazo, 2016

- ↑ Aguirre Urreta & Rawson, 2018

- ↑ Lazo, 2003

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Fernández et al., 2019

- ↑ Geologic Map, 2007, p.142

Bibliography

- General

- Balgord, Elizabeth A. 2017. Triassic to Neogene evolution of the south-central Andean arc determined by detrital zircon U-Pb and Hf analysis of Neuquén Basin strata, central Argentina (34°S–40°S). Lithosphere 9. 453–462.

- Balgord, Elizabeth A., and Barbara Carapa. 2014. Basin evolution of Upper Cretaceous–Lower Cenozoic strata in the Malargüe fold-and-thrust belt: northern Neuquen Basin, Argentina. Basin Research _. 1–24. Accessed 2019-02-22.

- Fernández, Diana E.; Luciana Giachetti; Stöhr Sabine; Ben Thuy; Damián E. Pérez; Marcos Comerio, and Pablo J. Pazos. 2019. Brittle stars from the Lower Cretaceous of Patagonia: first ophiuroid articulated remains for the Mesozoic of South America. Andean Geology 46. 421–432. Accessed 2019-06-15.

- Gómez Dacal, Alejandro R.; Lucía E. Gómez Peral; Luis A. Spalletti; Alcides N. Sial; Aron Siccardi, and Daniel G. Poiré. 2018. First record of the Valanginian positive carbon isotope anomaly in the Mendoza shelf, Neuquén Basin, Argentina: palaeoclimatic implications. Andean Geology 45. 111–129. Accessed 2019-02-22.

- Howell, John A.; Ernesto Schwartz; Luis A. Spalletti, and Gonzalo D. Veiga. 2005. The Neuquén Basin: An overview. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 252. 1–14. Accessed 2019-02-14.

- Leanza, Héctor A.; Federico Sattler; Ricardo S. Martínez, and Osvaldo Carbone. 2011. La formación Vaca Muerta y equivalentes (Jurásico tardío-Cretácico temprano) en la Cuenca Neuquina, 113–129. XVIII Congreso Geológico Argentino. Accessed 2019-02-14.

- Leanza, Héctor A. 2005. Las principales discordancias del Jurásico Superior y el Cretácico de la Cuenca Neuquina. Anales de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 57. 147–155. Accessed 2019-02-14.

- Leanza, H.A.; S. Apesteguia; F.E. Novas, and M.S. De la Fuente. 2004. Cretaceous terrestrial beds from the Neuquén Basin (Argentina) and their tetrapod assemblages. Cretaceous Research 25. 61–87. Accessed 2019-02-16.

- Lebinson, Fernando; Martín Turienzo; Natalia Sánchez; Vanesa Araujo; María Celeste D'Annunzio, and Luis Dimieri. 2018. The structure of the northern Agrio fold and thrust belt (37°30’ S), Neuquén Basin, Argentina. Andean Geology 45. 249–273. Accessed 2019-02-22.

- Moyano Bohórquez, Fernando. 2004. Los sistemas sedimentarios de la Formación Bajada Colorada (Cretácico Temprano) en el sur de la Cuenca Neuquina, Argentina, 1–250. Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Accessed 2019-02-14.

- Olivo, Mariano S.; Ernesto Schwartz, and Gonzalo D. Veiga. 2016. Modelo de acumulación y evolución secuencial del intervalo cuspidal de la Formación Quintuco en su área tipo: implicancias para las reconstrucciones paleogeográficas del margen austral de la Cuenca Neuquina durante el Valanginiano. Andean Geology 43. 215–239. Accessed 2019-02-22.

- Voglino, Sergio. 2017. Caracterización del Miembro Pilmatué de la Formación Agrio como reservorio no convencional de tipo shale (MSc. thesis), 1–196. Universidad Nacional de Río Negro. Accessed 2019-02-23.

- Paleontology

- Aguirre Urreta, Beatriz, and Peter F. Rawson. 2018. New Valanginian-Hauterivian neocomitid ammonites from the Neuquén Basin, Argentina. Cretaceous Research 88. 149–157. Accessed 2019-02-26.

- Aguirre Urreta, Beatriz; Darío G. Lazo, and Peter F. Rawson. 2012. Decapod Crustacea from the Agrio Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Neuquén Basin, Argentina. Palaeontology 55. 1091–1103. Accessed 2019-02-26.

- Aguirre Urreta, Beatriz, and Peter F. Rawson. 2012. Lower Cretaceous ammonites from the Neuquén Basin, Argentina: A new heteromorph fauna from the uppermost Agrio Formation. Cretaceous Research 35. 208–216. Accessed 2019-02-26.

- Aguirre Urreta, M.B. 1998. The ammonites Karakaschiceras and Neohoploceras (Valanginian Neocomitidae) from the Neuquén Basin, West-Central Argentina. Journal of Paleontology 72. 39–59. Accessed 2019-02-25.

- Cataldo, Cecilia S., and Darío G. Lazo. 2016. Taxonomy and paleoecology of a new gastropod fauna from dysoxic outer ramp facies of the Lower Cretaceous Agrio Formation, Neuquén Basin, west-central Argentina. Cretaceous Research 57. 165–189. Accessed 2019-02-26.

- Cataldo, C.S.. 2012. A new Early Cretaceous nerineoid gastropod from Argentina and its palaeobiogeographic and palaeoecological implications. Cretaceous Research 40. 51–60. Accessed 2019-02-25.

- Gouiric Cavalli, Soledad; Mariano Remírez, and Jürgen Kriwet. 2019. New pycnodontiform fishes (Actinopterygii, Neopterygii) from the Early Cretaceous of the Argentinian Patagonia. Cretaceous Research 94. 45–58. Accessed 2019-02-26.

- Kauffman, E.G., and H.A. Leanza. 2004. A Remarkable New Genus of Mytilidae (Bivalvia) from the Lower Cretaceous of Southwestern Gondwanaland. Journal of Paleontology 78. 1187–1191. Accessed 2019-02-25.

- Lazo, Darío G.; Marianella Talevi; Cecilia S. Cataldo; Beatriz Aguirre Urreta, and Marta S. Fernández. 2018. Description of ichthyosaur remains from the Lower Cretaceous Agrio Formation (Neuquén Basin, west-central Argentina) and their paleobiological implications. Cretaceous Research 89. 8–21. Accessed 2019-02-26.

- Lazo, Darío G. 2003. The genus Steinmanella (Bivalvia, Trigonioida) in the lower member of the Agrio Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Neuquén Basin, Argentina. Journal of Paleontology 77. 1069–1085. Accessed 2019-02-25.

- Geologic map

- Rodríguez, María F.; Héctor A. Leanza, and Matías Salvarredy Aranguren. 2007. Hoja Geológica 3969-II, NEUQUÉN, provincias del Neuquén, Río Negro y La Pampa 1:250,000, 1–165. Instituto de Geología y Recursos Minerales. Accessed 2019-02-23.

|