Earth:Airborne fraction

The airborne fraction is a scaling factor defined as the ratio of the annual increase in atmospheric CO2 to the CO2 emissions from human sources.[1] It represents the proportion of human emitted CO

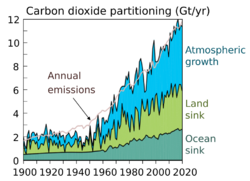

2 that remains in the atmosphere. Observations over the past six decades show that the airborne fraction has remained relatively stable at around 45%.[2] This indicates that the land and ocean's capacity to absorb CO2 has kept up with the rise in human CO2 emissions, despite the occurrence of notable interannual and sub-decadal variability, which is predominantly driven by the land's ability to absorb CO2. There is some evidence for a recent increase in airborne fraction, which would imply a faster increase in atmospheric CO2 for a given rate of human fossil-fuel burning.[3] Changes in carbon sinks can affect the airborne fraction as well.

Discussion about the trend of airborne fraction

Anthropogenic CO2 that is released into the atmosphere is partitioned into three components: approximately 45% remains in the atmosphere (referred to as the airborne fraction), while about 24% and 31% are absorbed by the oceans (ocean sink) and terrestrial biosphere (land sink), respectively.[4] If the airborne fraction increases, this indicates that a smaller amount of the CO2 released by humans is being absorbed by land and ocean sinks, due to factors such as warming oceans or thawing permafrost. As a result, a greater proportion of anthropogenic emissions remains in the atmosphere, thereby accelerating the rate of climate change. This has implications for future projections of atmospheric CO2 levels, which must be adjusted to account for this trend.[5] The question of whether the airborne fraction is rising, remaining steady at approximately 45%, or declining remains a matter of debate. Resolving this question is critical for comprehending the global carbon cycle and has relevance for policymakers and the general public.

The quantity “airborne fraction” is termed by Charles David Keeling in 1973, and studies conducted in the 1970s and 1980s defined airborne fraction from cumulative carbon inventory changes as,[5]

Or,

In which C is atmospheric carbon dioxide, t is time, FF is fossil-fuel emissions and LU is the emission to the atmosphere due to land use change.

At present, studies examining the trends in airborne fraction are producing contradictory outcomes, with emissions linked to land use and land cover change representing the most significant source of uncertainty. Some studies show that there is no statistical evidence of an increasing airborne fraction and calculated airborne fraction as,[6]

Where Gt is growth of atmospheric CO2 concentration, EFF is the fossil-fuel emissions flux, ELUC is the land use change emissions flux.

Another argument was presented that the airborne fraction of CO2 released by human activities, particularly through fossil-fuel emissions, cement production, and land-use changes, is on the rise.[7] Since 1959, the average CO2 airborne fraction has been 0.43, but it has shown an increase of approximately 0.2% per year over that period.[3]

On the other hand, the findings of another group suggest that the CO2 airborne fraction has declined by 0.014 ± 0.010 per decade since 1959.[8] This indicates that the combined land-ocean sink has expanded at a rate that is at least as rapid as anthropogenic emissions. The way they calculated the airborne fraction is:

Where, AF is airborne fraction and SF is sink fraction. ELULCC is the land use and land cover change emissions flux, EFF is the fossil-fuel emissions flux, and SO and SL are the ocean and land sinks, respectively.

The trend analyses of airborne fraction may be affected by external natural occurrences, such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), volcanic eruptions, and other similar events.[9] It is possible that the methodologies used in these studies to analyze the trend of airborne fraction are not robust, and therefore, the conclusions drawn from them are not warranted.

See also

- Greenhouse gas

- Carbon dioxide in Earth's atmosphere

- Total Carbon Column Observing Network

- Atmospheric carbon cycle

References

- ↑ Forster, P, V Ramaswamy, P Artaxo, et al. (2007) Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and in Radiative Forcing. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Solomon, S. et al. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK & New York, USA.[1]

- ↑ Friedlingstein, Pierre; O'Sullivan, Michael; Jones, Matthew W.; Andrew, Robbie M.; Hauck, Judith; Olsen, Are; Peters, Glen P.; Peters, Wouter et al. (2020). "Global Carbon Budget 2020" (in en). Earth System Science Data 12 (4): 3269–3340. doi:10.5194/essd-12-3269-2020. ISSN 1866-3516. Bibcode: 2020ESSD...12.3269F. https://essd.copernicus.org/articles/12/3269/2020/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Canadell, Josep G.; Le Quéré, Corinne; Raupach, Michael R.; Field, Christopher B.; Buitenhuis, Erik T.; Ciais, Philippe; Conway, Thomas J.; Gillett, Nathan P. et al. (2007). "Contributions to accelerating atmospheric CO2 growth from economic activity, carbon intensity, and efficiency of natural sinks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (47): 18866–18870. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702737104. ISSN 1091-6490. PMID 17962418.

- ↑ Bennedsen, Mikkel; Hillebrand, Eric; Koopman, Siem Jan (2019). "Trend analysis of the airborne fraction and sink rate of anthropogenically released CO2" (in English). Biogeosciences 16 (18): 3651–3663. doi:10.5194/bg-16-3651-2019. ISSN 1726-4170. Bibcode: 2019BGeo...16.3651B. https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/16/3651/2019/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Gloor, M.; Sarmiento, J. L.; Gruber, N. (2010). "What can be learned about carbon cycle climate feedbacks from the CO2 airborne fraction?" (in English). Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 10 (16): 7739–7751. doi:10.5194/acp-10-7739-2010. ISSN 1680-7316. Bibcode: 2010ACP....10.7739G. https://acp.copernicus.org/articles/10/7739/2010/.

- ↑ Raupach, M. R.; Gloor, M.; Sarmiento, J. L.; Canadell, J. G.; Frölicher, T. L.; Gasser, T.; Houghton, R. A.; Le Quéré, C. et al. (2014-07-02). "The declining uptake rate of atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub> by land and ocean sinks" (in en). Biogeosciences 11 (13): 3453–3475. doi:10.5194/bg-11-3453-2014. ISSN 1726-4189. Bibcode: 2014BGeo...11.3453R. https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/11/3453/2014/.

- ↑ Raupach, M. R.; Canadell, J. G.; Le Quéré, C. (2008). "Anthropogenic and biophysical contributions to increasing atmospheric CO2 growth rate and airborne fraction" (in English). Biogeosciences 5 (6): 1601–1613. doi:10.5194/bg-5-1601-2008. ISSN 1726-4170. Bibcode: 2008BGeo....5.1601R. https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/5/1601/2008/.

- ↑ van Marle, Margreet J. E.; van Wees, Dave; Houghton, Richard A.; Field, Robert D.; Verbesselt, Jan; van der Werf, Guido R. (2022). "New land-use-change emissions indicate a declining CO2 airborne fraction" (in en). Nature 603 (7901): 450–454. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04376-4. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 35296848. Bibcode: 2022Natur.603..450V. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-04376-4.

- ↑ Frölicher, Thomas Lukas; Joos, Fortunat; Raible, Christoph Cornelius; Sarmiento, Jorge Louis (2013). "Atmospheric CO2 response to volcanic eruptions: The role of ENSO, season, and variability". Global Biogeochemical Cycles 27 (1): 239–251. doi:10.1002/gbc.20028. Bibcode: 2013GBioC..27..239F. https://doi.org/10.1002/gbc.20028.

|