Earth:Sangay

| Sangay | |

|---|---|

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,286 m (17,343 ft) [1][2] |

| Prominence | 1,588 m (5,210 ft) [3] |

| Listing | Ultra |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 2°0′9″S 78°20′27″W / 2.0025°S 78.34083°W [4] |

| Naming | |

| English translation | The Frightener[5] |

| Language of name | Quechua |

| Pronunciation | [saŋˈɡaj][needs Quechua IPA] |

| Geography | |

| Location | Ecuador |

| Parent range | Andes |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Volcanic arc/belt | North Volcanic Zone |

| Last eruption | 1934 to 2024 (ongoing)[6] |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 4 August 1929[5] |

| Easiest route | Rock/Snow climb[7] |

Sangay (also known as Macas, Sanagay, or Sangai)[8] is an active stratovolcano in central Ecuador. It exhibits mostly strombolian activity. Geologically, Sangay marks the southern boundary of the Northern Volcanic Zone, and its position straddling two major pieces of crust accounts for its high level of activity. Sangay's approximately 500,000-year-old history is one of instability; two previous versions of the mountain were destroyed in massive flank collapses, evidence of which still litters its surroundings today.

Due to its remoteness, Sangay hosts a significant biological community with fauna such as the mountain tapir, giant otter, Andean cock-of-the-rock and king vulture. Since 1979, its ecological community has been protected as part of the Sangay National Park. Although climbing the mountain is hampered by its remoteness, poor weather conditions, river flooding, and the danger of falling ejecta, the volcano is regularly climbed, a feat first achieved by Robert T. Moore in 1929.

History

Folklore sourced from native people in the region compared Sangay to a lighthouse surrounded by a sea, which represented the dense jungle. The density of the jungle caused people to lose their way, but seeing ash and steam emissions from the volcano would help orient travelers along their way. Scientists have interpreted folklore like this as evidence of frequent and long-lasting eruptive activity at Sangay.[9]

In January 2024, archaeologists announced the discovery of archaeological sites on the east side of the volcano known as the Upano Valley sites. It is estimated that this cluster of urban settlements were inhabited between about 500 BCE to sometime between 300 and 600 CE. Altogether the cities may have reached a population between 15,000 and 100,000 people. They were surrounded by agricultural fields that archaeologist Stéphen Rostain speculates may have been particularly productive because their proximity to Sangay.[10][11]

Seventeen additional archaeological sites had been located prior to the 2024 announcement including potential monuments. An estimated 30,000 people lived in the region before Spanish occupation began in 1534. The Spanish prospected for gold on and around the volcano through the 16th and 17th Centuries and settled the area but expeditions undertaken in the 19th Century noted no inhabitants nearby. Modern development of the eastern side of the volcano began in the early 20th Century.[12]

The volcano and lands surrounding it were placed in a National Wildlife Reserve by the Ecuadorian government in 1975. This became Sangay National Park in 1979, which was expanded in 1992. The United Nations added it to their list of World Heritage Sites in 1983. From 1992 to 2005, poaching and human development led the UN to consider the site as being endangered but removed this status in 2005.[12]

The modern native inhabitants of the region primarily consist of Quechua people.[12] The name Sangay comes from the Quechuan languages and is translated as "the frightener."[5]

Geography

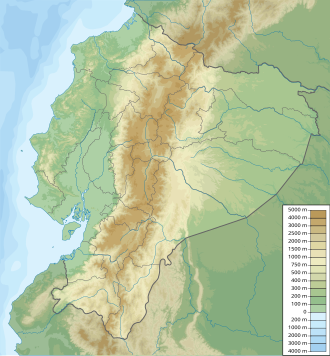

Sangay is on the eastern edge of the Andes Mountains in central Ecuador about 160 km (99 mi) south of Quito and 20 km (12 mi) east of Riobamba. It lies within Sangay National Park. Two nearby volcanoes, Tungurahua and El Altar, are also located within the national park. The three volcanoes reach exceed 5,000 m (16,000 ft) above sea level with El Altar being the tallest.[12]

The principal rivers draining Sangay are the Llushin, Palora, and the Upano, each of which have numerous smaller tributaries on the middle and upper slopes. Flash flooding from significant rainfall is frequent and erosion is a problem despite thick forests. Rivers drain east into the Amazon Basin. Topography is dominated by volcanic and glacial features. Hanging valleys from prior glaciation feature numerous waterfalls and lakes.[12]

Climate

Sangay reaches high enough to enjoy snow cover on its upper slopes despite its location near the Equator. It is disputed whether or not the volcano has a glacier though ice and snowfields are present.[13][14] The snow line in this part of South America lies approximately 4,800 m (15,700 ft) above sea level.[12]

The mountain environment leads to significant changes in precipitation across short distances. Prevailing winds are out of the east, causing rainfall to be greatest to the east where moisture is sourced from the Amazon rainforest.[15] Observed rainfall averages from 4,827 mm (190.0 in) per year at Pastaza to the northeast of the volcano to 423 mm (16.7 in) at Riobamba just 20 km (12 mi) west of the summit in the rain shadow.[16] Orographic lift and the Intertropical Convergence Zone are major factors in precipitation values.[12]

Annual temperatures see little variability but diurnal changes in temperature can be wide in more arid portions of the mountain's slopes. Higher elevations never rise above 0 °C (32 °F).[12] Climate change threatens the snowpack and the high altitude grasslands.[14]

Geology

Regional setting

Lying at the eastern edge of the Andean cordillera,[17] Sangay was formed by volcanic processes associated with the subduction of the Nazca Plate under the South American Plate at the Peru–Chile Trench.[18] It is the southernmost volcano in the Northern Volcanic Zone, a subgroup of Andean volcanoes whose northern limit is Nevado del Ruiz in Colombia.

The next active volcano in the chain, Sabancaya, is in Peru, 1,600 km (990 mi) to the south. Sangay is above a seismogenic tectonic slab about 130 km (80 mi) beneath Sabancaya, reflecting a sharp difference in the thermal character of the subducted oceanic crust, between older rock beneath southern Ecuador and Peru (dated more than 32 million years old), and younger rock under northern Ecuador and Colombia (dated less than 22 million years old). The older southern rock is more thermally stable than the northern rock, and to this is attributed the long break in volcanic activity in the Andes; Sangay occupies a position at the boundary between these two bodies, accounting for its high level of activity.[17]

Formation

Sangay developed in three distinct phases. Its oldest edifice, formed between 500,000 and 250,000 years ago, is evidenced today by a wide scattering of material opening to the east, defined by a crest about 4,000 m (13,120 ft) high, pockmarked by secondary ridges; it is thought to have been 15–16 km (9–10 mi) in diameter, with a summit 2 to 3 km (1 to 2 mi) southeast of the present summit. The curved shape of the remnants of this first structure shows that it suffered a massive flank collapse, scattering the nearby forest lowlands with debris and causing a large part of its southern caldera wall to slide off the mountain, forming an embayment lower on its slopes. This 400 m (1,312 ft) thick block, the best-preserved specimen of Sangay's early construction, consists of sequentially layered breccias, pyroclastic flows, and lahar deposits. Acidic andesites with just under 60% silicon dioxide dominate these flows, but more basic andesites can be found as well.[17]

Sangay's second edifice began to form anew after the massive sector collapse that damaged the first, being constructed between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago. Remnants of its second structure are within the southern and eastern parts of the debris from its first collapse; some remnants of the volcano lie to the west and north as well. Sangay's second structure is believed to have had an east-to-west elongated summit, and like its first summit structure, it suffered a catastrophic collapse that created a debris avalanche 5 km (3 mi) wide and up to 20 km (12 mi) in length. It was likely less voluminous than the volcano's first version, and its summit lay near Sangay's current summit.[17]

Recent activity

Sangay currently forms an almost perfect glacier-capped cone 5,286 m (17,343 ft) high, with a 35° slope and a slight northeast-southwest tilt.[17] Its eastern flank marks the edge of the Amazon Rainforest, and its western flank is a flat plain of volcanic ash, sculpted into steep gorges up to 600 m (1,970 ft) deep by heavy rainfall.[4] It has a west-east trending summit ridge, capped by three active craters and a lava dome. Sangay has been active in its current form for at least 14,000 years, and is still filling out the area left bare by its earlier incarnations, being smaller than either of them. Uniquely, in its 500,000 years of activity, its magma plume has never changed composition or moved a significant distance.[17]

Mainly andesitic in composition, Sangay is highly active. The earliest report of a historical eruption was in 1628;[4] ash fell as far away as Riobamba, located 50 km (31 mi) northwest of Sangay, and was severe enough to cover pastures and starve local livestock.[19] The volcano erupted again in 1728, remaining essentially continuously active through 1916,[4] with particularly heavy activity in 1738–1744, 1842–1843, 1849, 1854–1859, 1867–1874, 1872, and 1903.[17] After a brief pause, it erupted again on August 8, 1934, and has not completely quelled ever since,[4] with heavy eruptive periods occurring in 1934–1937 and 1941–1942.[17][20]

Eruptions at Sangay exhibit strombolian activity, producing ashfall, lava flows, pyroclastic flows, and lahars.[19] All known eruptions at the volcano have had a Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) of 3 or less.[4] Despite its activity, Sangay is located in a remote, uninhabited region; only a large Plinian eruption could threaten occupied areas 30–100 km (19–62 mi) to its west.[19] Nonetheless, a flank collapse on its eastern side, possible given the volcano's construction and history, could displace nearby forest and possibly affect settlements.[17] Access to the volcano is difficult, as its current eruptive state constantly peppers the massif with molten rock and other ejecta. For these reasons it is not nearly as well-studied as other, similarly active volcanoes in the Andes and elsewhere; the first detailed study of the volcano was not published until 1999.[17]

21st Century

The current phase of the ongoing eruption began on 26 March 2019,[21] and it has remained in continuing eruption status (intermittent eruptive events without a break of 3 months or more) as of January 2024.[22]

On 15 June 2022, the United States' National Weather Service issued an ashfall advisory as the volcano went into a state of unrest, producing a plume of volcanic ash. Mariners traveling in the vicinity were cautioned about the possibility of debris.[23][24]

Ecology

Sangay is one of two active volcanoes in the Sangay National Park, the other being Tungurahua to the north. As such it has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1983. The area's isolation has allowed it to maintain a pristine ecology relatively untouched by human interaction, and the park hosts a biome ranging from alpine glaciers on the volcanoes' peaks to tropical forest on their flanks. Altitude and rainfall are the most significant local factors affecting fauna, and therefore the lushest ecosystems are found on the wetter parts of the volcano's eastern slope.[25]

The highest level below the snowline is dominated by lichen and bryophytes. Below this lies a zone of small trees and shrubs which develops into montane forest, principally in western valleys and on well-irrigated eastern slopes, which occurs below 3,750 m (12,303 ft). Tree heights develop from 5 m (16 ft) near the top to up to 12 m (39 ft) below 3,000 m (9,843 ft); below 2,000 m (6,562 ft), subtropical rainforest is present, with temperatures between 18 and 24 °C (64 and 75 °F) and up to 500 cm (196.9 in) of rainfall.[25]

Fauna is similarly distributed, with distinct altitudinal zonation present. The highest altitudes support the endangered mountain tapir, cougar, guinea pig, and Andean fox. Lower down, the spectacled bear, jaguar, ocelot, margay, white-tailed deer, brocket deers, northern pudú, and endangered giant otter can all be found. Bird species common in the area include the Andean condor, Andean cock-of-the-rock, giant hummingbird, torrent duck, king vulture, and swallow-tailed kite.[25]

Recreation

Sangay can be and has been climbed. It was first ascended in 1929 by Robert T. Moore, prior to its current eruption beginning in 1934.[5][26] However, the volcano's current active state presents dangers to mountaineers in the form of falling ejecta;[7] in 1976, two members of an expedition on the volcano were struck and killed by falling debris. In addition, the volcano is located in a remote region with poor roads and is difficult to access, and periods of heavy rainfall can flood rivers and cause landslides, rendering the mountain routes impassable. Nonetheless, the Instituto Ecuatoriano Forestal y de Areas Naturales, which maintains an office near the mountain, facilitate such activities by providing local guides and rooms for rent to visitors. Ascension takes between 7 and 10 days from Quito. Conditions on the volcano are usually very wet and foggy, which may impair visibility significantly during the ascent.[7]

See also

- Lists of volcanoes

- List of volcanoes in Ecuador

References

- ↑ "Ecuador: 15 Mountain Summits with Prominence of 1,500 meters or greater". Peaklist.org. http://www.peaklist.org/WWlists/ultras/ecuador.html.

- ↑ Estimate based on SRTM and ASTER data, which agree that the often quoted elevation of 5230 metres is too low.

- ↑ Jonathan de Ferranti and Aaron Maizlish. "Ecuador". http://peaklist.org/WWlists/ultras/ecuador.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Sangay". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. https://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=352090.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Jason Wilson (2009). The Andes: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-19-538636-3. https://archive.org/details/andesculturalhis0000wils. Retrieved 5 February 2012. "Sangay quechua."

- ↑ "Sangay: Weekly Reports". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. https://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=352090#January2024.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Yossi Brain (2000). Ecuador: A Climbing Guide. The Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-0-89886-729-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=TOD6ndB0LMUC&q=Sangay&pg=PA169. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ↑ "Sangay: Synonyms and subfeatures". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. https://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=352090.

- ↑ Heberer, Mikelia (2021-07-26). "A Story About Sangay" (in en). https://local.storymapsdev.arcgis.com:3443/stories/7e60dbdb34074b1abdef73c03e155624.

- ↑ Wade, Lizzie (11 January 2024). "Laser mapping reveals oldest Amazonian cities, built 2500 years ago". Science. doi:10.1126/science.zzti03q. https://www.science.org/content/article/laser-mapping-reveals-oldest-amazonian-cities-built-2500-years-ago. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ↑ Smith, Kiona N. (11 January 2024). "Ancient Amazon Civilization Developed Unique Form of 'Garden Urbanism'". Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/ancient-amazon-civilization-developed-unique-form-of-garden-urbanism/.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 UNEP-WCMC (2017-05-22). "SANGAY NATIONAL PARK" (in en). http://world-heritage-datasheets.unep-wcmc.org/datasheet/output/site/sangay-national-park.

- ↑ "USGS P 1386-I -- Ecuador - Ice Balance". https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/p1386i/ecuador/balance.html.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Sangay National Park" (in en-GB). https://www.naturalworldheritagesites.org/sites/sangay-national-park/.

- ↑ Rollenbeck, Rütger; Bendix, Jörg (2011-02-01). "Rainfall distribution in the Andes of southern Ecuador derived from blending weather radar data and meteorological field observations". Atmospheric Research 99 (2): 277–289. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2010.10.018. ISSN 0169-8095. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169809510002826.

- ↑ Santillan Quiroga, Luis Miguel; Cocca, Daniele; Ballesteros3, Juan Carlos Caicedo (July 2023). "Precipitation analysis with R-Climdex and RH test V4, for the ESPOCH weather station, Riobamba-Ecuador, in the period 1976-2017". RENDICONTI ONLINE DELLA SOCIETÀ GEOLOGICA ITALIANA 60/2023: 142. doi:10.3301/ROL.2023.17. https://www.rendicontisocietageologicaitaliana.it/297/article-4187/precipitation-analysis-with-r-climdex-and-rh-test-v4-for-the-espoch-weather-station-riobamba-ecuador-in-the-period-1976-2017.html.

- ↑ 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 Monzier, Michel (1999). "Sangay volcano, Ecuador: structural development, present activity and petrology". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research (Elsevier) 90 (1–2): 49–79. doi:10.1016/S0377-0273(99)00021-9. ISSN 0377-0273. Bibcode: 1999JVGR...90...49M.

- ↑ Miller, Meghan S. (24 January 2009). "Upper mantle structure beneath the Caribbean-South American plate boundary from surface wave tomography". Journal of Geophysical Research (American Geophysical Union) 114 (B1): B01312. doi:10.1029/2007JB005507. Bibcode: 2009JGRB..114.1312M.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 John Seach. "Sangay Volcano – John Seach". http://www.volcanolive.com/sangay.html.

- ↑ "Global Volcanism Program | Sangay". https://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=352090.

- ↑ "Reventador Eruption History - Global Volcanism Program". Smithsonian. http://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vn=352010&vtab=Eruptions.

- ↑ "Global Volcanism Program | Current Eruptions". https://volcano.si.edu/gvp_currenteruptions.cfm.

- ↑ "High Seas Forecast (Tropical NE Pacific)". https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/text/MIAHSFEP2.shtml.

- ↑ "Offshore Waters Forecast (E Pacific Offshore of Central America/Colombia/Ecuador)". https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/text/MIAOFFPZ8.shtml.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 "Sangay National Park". World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/260.

- ↑ Lewis, G. Edward (1950). "El Sangay, Fire-breathing Giant of the Andes". National Geographic (National Geographic Society): 17–24.

External links

- National Geographic: Collecting Clues to Solve a Volcanic Mystery

- Sangay Volcano Erupts, Turns Day to Night in Ecuador - Sept. 20, 2020

|