Earth:Year Without a Summer

| Year Without a Summer | |

|---|---|

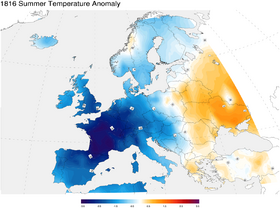

1816 summer temperature anomaly in Europe compared with average temperatures from 1971 to 2000 | |

| Volcano | Mount Tambora |

| Start date | Eruption occurred on April 10, 1815 |

| Type | Ultra-Plinian |

| Location | Lesser Sunda Islands, Dutch East Indies (now Republic of Indonesia) |

| Impact | Caused a volcanic winter that dropped temperatures by 0.4–0.7 °C (or 0.7–1 °F) worldwide |

The year 1816 is known as the Year Without a Summer because of severe climate abnormalities that caused average global temperatures to decrease by 0.4–0.7 °C (0.7–1 °F).[1] Summer temperatures in Europe were the coldest of any on record between 1766 and 2000,[2] resulting in crop failures and major food shortages across the Northern Hemisphere.[3]

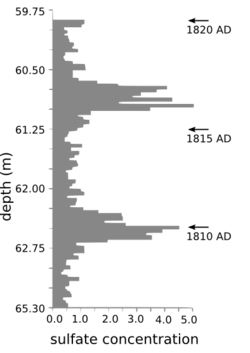

Evidence suggests that the anomaly was predominantly a volcanic winter event caused by the massive 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in April in modern-day Indonesia (commonly referred to as the Dutch East Indies at the time). This eruption was the largest in at least 1,300 years (after the hypothesized eruption causing the volcanic winter of 536); its effect on the climate may have been exacerbated by the 1814 eruption of Mayon in the Philippines. The significant amount of volcanic ash and gases released into the atmosphere blocked sunlight, leading to global cooling.

Countries such as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Bourbon Restoration France experienced significant hardship, with food riots and famine becoming common. The situation was exacerbated by the fact that Europe was still recovering from the Napoleonic Wars, adding to the socio-economic stress.

North America also faced extreme weather conditions. In the eastern United States, a persistent "dry fog" dimmed the sunlight, causing unusual cold and frost throughout the summer months. Crops failed in regions like New England, leading to food shortages and economic distress. These conditions forced many families to leave their homes in search of better farming opportunities, contributing to Westward expansion.

Description

The Year Without a Summer was an agricultural disaster; historian John D. Post called it "the last great subsistence crisis in the Western world".[4][5] The climatic aberrations of 1816 had their greatest effect on New England (US), Atlantic Canada, and Western Europe.[6]

The main cause of the Year Without a Summer is generally held to be a volcanic winter created by the April 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora on Sumbawa.[7][8][9] The eruption had a volcanic explosivity index (VEI) ranking of 7, and ejected at least 37 km3 (8.9 cu mi) of dense-rock equivalent material into the atmosphere.[10] It remains the most recent confirmed VEI-7 eruption to date.[11]

Other large volcanic eruptions (of at least VEI-4) around this time include:

- The 1808 mystery eruption in the southwestern Pacific Ocean

- 1812, La Soufrière on Saint Vincent in the Caribbean

- 1812, Awu in the Sangihe Islands, Dutch East Indies

- 1813, Suwanosejima in the Ryukyu Islands

- 1814, Mayon in the Philippines

These eruptions had built up a substantial amount of atmospheric dust, and thus temperatures fell worldwide as the airborne material blocked sunlight in the stratosphere.[12] According to a 2012 analysis by Berkeley Earth, the 1815 Tambora eruption caused a temporary drop in the Earth's average land temperature of about one degree Celsius; smaller temperature drops were recorded from the 1812–1814 eruptions.[13]

The Earth had already been in a centuries-long period of cooling that began in the 14th century. Known today as the Little Ice Age, it had already caused considerable agricultural distress in Europe. The eruption of Tambora occurred near the end of the Little Ice Age, exacerbating the background global cooling of the period.[14]

This period also occurred during the Dalton Minimum, a period of relatively low solar activity from 1790 to 1830. May 1816 had the lowest Wolf number (0.1) to date since records on solar activity began. It is not yet known, however, if and how changes in solar activity affect Earth's climate, and this correlation does not prove that lower solar activity produces global cooling.[15]

Africa

No direct evidence for conditions in the Sahel region have been found, though conditions from surrounding areas have implied above-normal rainfall. Below the Sahel, the coastal regions of West Africa likely experienced below-normal levels of precipitation. Severe storms affected the South African coast during the Southern Hemisphere winter. On July 29–30, 1816, a violent storm occurred near Cape Town, South Africa, which brought forceful northerly winds and hail and caused severe damage to shipping.[16]

Asia

The monsoon season in China was disrupted, resulting in overwhelming floods in the Yangtze Valley. Fort Shuangcheng reported fields disrupted by frost and conscripts deserting as a result. Summer snowfall or otherwise mixed precipitation was reported in various locations in Jiangxi and Anhui. In Taiwan, snow was reported in Hsinchu and Miaoli, and frost was reported in Changhua.[17] A large-scale famine in Yunnan helped reverse the fortunes of the ruling Qing dynasty.[17][18]

In India, the delayed summer monsoon caused late torrential rains that aggravated the spread of cholera from a region near the Ganges in Bengal to as far as Moscow.[19] In Bengal, abnormal cold and snow was reported in the winter monsoon.[16]

In Japan, which was still cautious after the cold-weather-related Great Tenmei famine of 1782–1788, cold damaged crops, but no crop failures were reported and there was no adverse effect on population.[20]

Europe

As a result of the series of volcanic eruptions in the 1810s, crops had been poor for several years; the final blow came in 1815 with the eruption of Tambora. Europe, still recuperating from the Napoleonic Wars, suffered from widespread food shortages, resulting in its worst famine of the century.[22][23][24][25] Low temperatures and heavy rains resulted in failed harvests in Great Britain and Ireland. Famine was prevalent in north and southwest Ireland, following the failure of wheat, oat, and potato harvests. Food prices rose sharply throughout Europe.[26] With the cause of the problems unknown, hungry people demonstrated in front of grain markets and bakeries. Food riots took place in many European cities. Though riots were common during times of hunger, the food riots of 1816 and 1817 were the most violent period on the continent since the French Revolution.[23]

Between 1816 and 1819, major typhus epidemics occurred in parts of Europe, including Ireland, Italy, Switzerland, and Scotland, precipitated by the famine. More than 65,000 people died as the disease spread out of Ireland.[22][23]

The long-running Central England temperature record reported the eleventh coldest year on record since 1659, as well as the third coldest summer and the coldest July on record.[27] Widespread flooding of Europe's major rivers is attributed to the event, as is frost in August. Hungary experienced snowfall colored brown by volcanic ash; in northern Italy, red snow fell throughout the year.[22]

Flooding impeded navigation of major rivers like the Rhine, including the transportation of grain. In German-speaking lands, (particularly inland), prices rose, and though only Wurttemberg saw deaths exceed births, emigration caused a greater population loss than excess mortality. Austria avoided famine.[28]

In Switzerland, famine was limited to the east, which was densely populated and more industrialized.[28] In western Switzerland, the summers of 1816 and 1817 were so cold that an ice dam formed below a tongue of the Giétro Glacier in the Val de Bagnes, creating a lake. Despite engineer Ignaz Venetz's efforts to drain the growing lake, the ice dam collapsed catastrophically in June 1818, killing forty people in the resulting flood.[29]

Harvests were not affected everywhere. In Scandinavia and the northern Baltic regions were almost normal, as they were in eastern Europe and western Russia. Indeed, the Russian Emperor Alexander I was able to donate grain to western Europe.[30]

North America

In the spring and summer of 1816, a persistent "dry fog" was observed in parts of the eastern United States. The fog reddened and dimmed sunlight such that sunspots were visible to the naked eye. Neither wind nor rainfall dispersed the "fog", retrospectively characterized by Clive Oppenheimer as a "stratospheric sulfate aerosol veil".[31]

The weather was not in itself a hardship for those accustomed to long winters. Hardship came from the weather's effect on crops and thus on the supply of food and firewood. The consequences were felt most strongly at higher elevations, where farming was already difficult even in good years. In May 1816, frost killed off most crops in the higher elevations of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, and upstate New York.[32] On June 6, snow fell in Albany, New York, and Dennysville, Maine.[24] In Cape May, New Jersey, frost was reported five nights in a row in late June, causing extensive crop damage.[33] Though fruit and vegetable crops survived in New England, corn was reported to have ripened so poorly that no more than a quarter of it was usable for food, and much of it was moldy and not even fit for animal feed.[22] The crop failures in New England, Canada, and parts of Europe caused food prices to rise sharply. In Canada, Quebec ran out of bread and milk, and Nova Scotians found themselves boiling foraged herbs for sustenance.[22]

Sarah Snell Bryant, of Cummington, Massachusetts, wrote in her diary: "Weather backward."[34] At the Church Family of Shakers near New Lebanon, New York, Nicholas Bennet wrote in May 1816 that "all was froze" and the hills were "barren like winter". Temperatures fell below freezing almost every day in May. The ground froze on June 9; on June 12, the Shakers had to replant crops destroyed by the cold. On July 7, it was so cold that all of their crops had stopped growing. Salem, Massachusetts physician Edward Holyoke—a weather observer and amateur astronomer—while in Franconia, New Hampshire, wrote on June 7, "exceedingly cold. Ground frozen hard, and squalls of snow through the day. Icicles 12 inches long in the shade of noon day." After a lull, by August 17, Holyoke noted an abrupt change from summer to winter by August 21, when a meager bean and corn crop were killed. "The fields," he wrote, "were as empty and white as October."[35] The Berkshires saw frost again on August 23, as did much of New England and upstate New York.[36]

Massachusetts historian William G. Atkins summed up the disaster:

Severe frosts occurred every month; June 7th and 8th snow fell, and it was so cold that crops were cut down, even freezing the roots ... In the early Autumn when corn was in the milk [the endosperm inside the kernel was still liquid][37] it was so thoroughly frozen that it never ripened and was scarcely worth harvesting. Breadstuffs were scarce and prices high and the poorer class of people were often in straits for want of food. It must be remembered that the granaries of the great west had not then been opened to us by railroad communication, and people were obliged to rely upon their own resources or upon others in their immediate locality.[38]

In July and August, lake and river ice was observed as far south as northwestern Pennsylvania. Frost was reported in Virginia on August 20 and 21.[39] Rapid, dramatic temperature swings were common, with temperatures sometimes reverting from normal or above-normal summer temperatures as high as 95 °F (35 °C) to near-freezing within hours. Thomas Jefferson, by then retired from politics to his estate at Monticello in Virginia, sustained crop failures that sent him further into debt. On September 13, a Virginia newspaper reported that corn crops would be one half to two-thirds short and lamented that "the cold as well as the drought has nipt the buds of hope".[40] A Norfolk, Virginia, newspaper reported:

It is now the middle of July, and we have not yet had what could properly be called summer. Easterly winds have prevailed for nearly three months past ... the sun during that time has generally been obscured and the sky overcast with clouds; the air has been damp and uncomfortable, and frequently so chilling as to render the fireside a desirable retreat.[41]

Regional farmers succeeded in bringing some crops to maturity, but corn and other grain prices rose dramatically. The price of oats, for example, rose from 12¢ per bushel in 1815 to 92¢ per bushel in 1816. Crop failures were aggravated by inadequate transportation infrastructure; with few roads or navigable inland waterways and no railroads, it was prohibitively expensive to import food in most of the country.[42]

Maryland experienced brown, bluish, and yellow snowfall in April and May, colored by volcanic ash in the atmosphere.[22]

South America

A newspaper account of northeastern Brazil was published in the United Kingdom:

By an arrival at Liverpool we have received accounts from Pernambuco of the 8th of Feb. [1817], which state that a most uncommon drought has been experienced in the tropical regions of the Brazils, or that part of the country between Pernambuco and Rio Janiero. By this circumstance all the streams had been dried up, the cattle were dying or dead, and all the population emigrating to the borders of the great rivers in search of water. The greatest distress prevailed, provisions were wanting, and the mills completely at a stand. They have no windmills, so that no corn could be ground. Vessels have been sent from Pernambuco to the United States to fetch flour, and what had tended to increase this distress was the interruption of the coasting trade through the dread of war with Buenos Ayres.[16]

Societal effects

High levels of tephra in the atmosphere caused a haze to hang over the sky for several years after the eruption, and created rich red hues in sunsets. Paintings during the years before and after seem to confirm that these striking reds were not present before Mount Tambora's eruption,[43][44] and depict moodier, darker scenes, even in the light of both the sun and the moon. Caspar David Friedrich's The Monk by the Sea (ca. 1808–1810) and Two Men by the Sea (1817) indicate this shift of mood.[43]

A 2007 study analyzing paintings created between the years 1500 and 1900 around the times of notable volcanic events found a correlation between volcanic activity and the amount of red used in the painting.[44][43] High levels of tephra in the atmosphere led to spectacular sunsets during this period, as depicted in the paintings of J. M. W. Turner, and may have given rise to the yellow tinge predominant in his paintings such as Chichester Canal (1828). Similar phenomena were observed after the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, and on the West Coast of the United States following the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo.[44]

The lack of oats to feed horses may have inspired the German inventor Karl Drais to research new ways of horseless transportation, which led to the invention of the draisine and velocipede, a precursor of the bicycle.[45]

The crop failures of the "Year without a Summer" may have shaped the settlement of the Midwestern United States, as many thousands of people left New England for western New York and the Northwest Territory in search of a more hospitable climate, richer soil, and better growing conditions.[46] Indiana became a state in December 1816, and Illinois did two years later. British historian Lawrence Goldman has suggested that migration into the burned-over district of upstate New York was responsible for centering the abolitionist movement in that region.[47]

According to historian L. D. Stillwell, Vermont alone experienced a decrease in population of between 10,000 and 15,000 in 1816 and 1817, erasing seven previous years of population growth.[5] Among those who left Vermont were the family of Joseph Smith, who moved from Norwich, Vermont, to Palmyra, New York.[48] This move precipitated the series of events that culminated in Smith founding the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[19]

In June 1816, "incessant rainfall" during the "wet, ungenial summer" forced Mary Shelley,[49][50] Percy Bysshe Shelley, Lord Byron, John William Polidori, and their friends to stay indoors at Villa Diodati for much of their Swiss holiday.[47][51][50] Inspired by a collection of German ghost stories that they had read, Lord Byron proposed a contest to see who could write the scariest story, leading Shelley to write Frankenstein[50] and Lord Byron to write "A Fragment", which Polidori later used as inspiration for The Vampyre[50] – a precursor to Dracula. These days inside Villa Diodati, remembered fondly by Mary Shelley,[50] were occupied by opium use and intellectual conversations.[52] After listening intently to one of these conversations, she awoke with the image of Victor Frankenstein kneeling over his monstrous creation, and thus was inspired to write Frankenstein.[50] Lord Byron was inspired to write the poem "Darkness" by a single day when "the fowls all went to roost at noon and candles had to be lit as at midnight".[47] The imagery in the poem is starkly similar to the conditions of the Year Without a Summer:[53]

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguish'd, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day

Justus von Liebig, a chemist who had experienced the famine as a child in Darmstadt, later studied plant nutrition and introduced mineral fertilizers.[54]

Comparable events

- Toba catastrophe, a hypothetical cooling during the Late Pleistocene following the eruption 74,000 years ago.

- The 1628–1626 BC climate disturbances, usually attributed to the Minoan eruption of Santorini

- The Hekla 3 eruption of about 1200 BC, contemporary with the historical Bronze Age collapse

- The Hatepe eruption (sometimes referred to as the Taupō eruption), around AD 180

- The winter of 536 has been linked to the effects of a volcanic eruption, possibly at Krakatoa, or of Ilopango in El Salvador

- The Heaven Lake eruption of Paektu Mountain between modern-day North Korea and the People's Republic of China, in 969 (± 20 years), is thought to have had a role in the downfall of Balhae

- The 1257 Samalas eruption of Mount Rinjani on the island of Lombok in 1257

- The 1452/1453 mystery eruption has been implicated in events surrounding the Fall of Constantinople in 1453

- An eruption of Huaynaputina, in Peru, caused 1601 to be the coldest year in the Northern Hemisphere for six centuries (see Russian famine of 1601–1603); 1601 consisted of a bitterly cold winter, a cold, frosty, nonexistent spring, and a cool, cloudy, wet summer

- An eruption of Laki, in Iceland, was responsible for up to hundreds of thousands of fatalities throughout the Northern Hemisphere (over 25,000 in England alone), and one of the coldest winters ever recorded in North America, 1783–1784; long-term consequences included poverty and famine that may have contributed to the French Revolution in 1789.[55]

- The 1883 eruption of Krakatoa caused average Northern Hemisphere summer temperatures to fall by as much as 1.2 °C (2.2 °F). One of the wettest rainy seasons in recorded history followed in California during 1883–1884.

See also

- Earth:1458 mystery eruption – Large volcanic eruption of uncertain location

- Astronomy:Dalton Minimum – Period of low solar activity from 1790 to 1830

- Earth:Global cooling – Discredited 1970s hypothesis of imminent cooling of the Earth

- Earth:Little Ice Age – A period of cooling after the Medieval Warm Period that lasted from the 16th to the 19th century

- Social:Tambora culture

- Earth:Timeline of volcanism on Earth – None

Notes

- ↑ Stothers, Richard B. (1984). "The Great Tambora Eruption in 1815 and Its Aftermath". Science 224 (4654): 1191–1198. doi:10.1126/science.224.4654.1191. PMID 17819476. Bibcode: 1984Sci...224.1191S.

- ↑ Schurer, Andrew P.; Hegerl, Gabriele C.; Luterbacher, Jürg; Brönnimann, Stefan; Cowan, Tim; Tett, Simon F. B.; Zanchettin, Davide; Timmreck, Claudia (September 17, 2019). "Disentangling the causes of the 1816 European year without a summer" (in en). Environmental Research Letters 14 (9): 094019. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab3a10. ISSN 1748-9326. Bibcode: 2019ERL....14i4019S.

- ↑ "Saint John New Brunswick Time Date". New-brunswick.net. http://new-brunswick.net/Saint_John/timedate.html.

- ↑ Post, John D. (1977) (in en-us). The last great subsistence crisis in the Western World. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801818509.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Evans, Robert. "Blast from the Past" (in en-us). p. 2. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/blast-from-the-past-65102374/.

- ↑ "Is the Meghalayan Event a Tipping Point in Geology?". July 23, 2018. https://thewire.in/the-sciences/is-the-meghalayan-event-a-tipping-point-in-geology.

- ↑ "The Year Without a Summer". http://www.bellrock.org.uk/misc/misc_year.htm.

- ↑ Tully, Anthony. Tambora, Indonesian Volcano (Tambora Volcano Part I): Tambora: The Year Without A Summer[Usurped!], Indodigest, archived on June 15, 2006, from the original[Usurped!].

- ↑ Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles: A History of Java; Black, Parbury, and Allen for the Hon. East India Company 1817; reprinted in the Cambridge Library Collection, 2010.

- ↑ Kandlbauer, J.; Sparks, R. S. J. (October 1, 2014). "New estimates of the 1815 Tambora eruption volume" (in en). Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 286: 93–100. doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2014.08.020. ISSN 0377-0273. Bibcode: 2014JVGR..286...93K. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377027314002601. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Clive (2003). "Climatic, environmental and human consequences of the largest known historic eruption: Tambora volcano (Indonesia) 1815". Progress in Physical Geography 27 (2): 230–259. doi:10.1191/0309133303pp379ra. Bibcode: 2003PrPG...27..230O.

- ↑ Ljungqvist, F. C.; Krusic, P. J.; Sundqvist, H. S.; Zorita, E.; Brattström, G.; Frank, D. (2016). "Why does the stratosphere cool when the troposphere warms? " RealClimate". Nature (Realclimate.org) 532 (7597): 94–98. doi:10.1038/nature17418. PMID 27078569. Bibcode: 2016Natur.532...94L. http://www.realclimate.org/index.php/archives/2004/12/why-does-the-stratosphere-cool-when-the-troposphere-warms/. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ↑ Berkeley Earth Releases New Analysis , July 29, 2012

- ↑ "Environmental History Resources – The Little Ice Age, c. 1300–1870". Environmental History Resources. http://www.eh-resources.org/timeline/timeline_lia.html.

- ↑ "Dalton minimum | solar phenomenon [1790–1830 | Britannica"] (in en). https://www.britannica.com/science/Dalton-minimum.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Chenoweth, Michael (September 1, 1996). "Ships' Logbooks and "The Year Without a Summer"" (in en). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 77 (9): 2077–2094. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<2077:SLAYWA>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0003-0007. Bibcode: 1996BAMS...77.2077C.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Serious Famine in Yunnan (1815–1817) and the Eruption of Tambola Volcano Fudan Journal (Social Sciences) No. 1 2005, archived on March 26, 2009, from the original

- ↑ Broad, William J. (September 2, 2015). "200年前,那場火山爆發改變了世界" (in zh-hant). 紐約時報中文網. https://cn.nytimes.com/lifestyle/20150902/t02summer/zh-hant/. Retrieved 2019-07-17.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Facts – Year Without Summer. , Extreme Earth, Discovery Channel.

- ↑ "夏のない年 from turning-point.info". http://turning-point.info/YearWithoutaSummer.html.

- ↑ Dai, Jihong; Mosley-Thompson, Ellen; Thompson, Lonnie G. (1991). "Ice core evidence for an explosive tropical volcanic eruption six years preceding Tambora". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 96 (D9): 17, 361–317, 366. doi:10.1029/91jd01634. Bibcode: 1991JGR....9617361D.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Fagan, Brian M. (2000). The Little Ice Age : how climate made history, 1300–1850. Oliver Wendell Holmes Library Phillips Academy. New York,: Basic Books. http://archive.org/details/littleiceagehowc0000faga.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Stommel, Henry (1983). Volcano weather : the story of 1816, the year without a summer. Seven Seas Press. ISBN 0915160714.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Oppenheimer 2003.

- ↑ "The 'year without a summer' in 1816 produced massive famines and helped stimulate the emergence of the administrative state", observes Albert Gore, Earth in the Balance: Ecology and the human spirit, 2000: 79.

- ↑ Warde, Paul; Fagan, Brian (January 2002). "The Little Ice Age. How Climate Made History 1300–1850". Environmental History 7 (1): 133. doi:10.2307/3985463. ISSN 1084-5453.

- ↑ "Met Office Hadley Centre Central England Temperature Data Download". https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadcet/data/download.html.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Collet, Dominik; Krämer, Daniel (2017). "5 - Germany, Switzerland and Austria". Famine in European History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 109–111, 117. ISBN 9781107179936. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/110D3AEE6E978DFE51BA66BE43116A22. Retrieved 2025-04-05.

- ↑ The flood is fully described in Jean M. Grove, Little Ice Ages, Ancient and Modern (as The Little Ice Age 1988) revised edition. 2004: 161.

- ↑ Luterbacher, J.; Pfister, C. (2015). "The year without a summer" (in en). Nature Geoscience 8 (4): 246–248. doi:10.1038/ngeo2404. ISSN 1752-0894. https://www.nature.com/articles/ngeo2404.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Clive (2003), "Climatic, environmental and human consequences of the largest known historic eruption: Tambora volcano (Indonesia) 1815", Progress in Physical Geography 27 (2): 230, doi:10.1191/0309133303pp379ra, Bibcode: 2003PrPG...27..230O.

- ↑ Heidorn, Keith C. (July 1, 2000). "Weather Doctor's Weather People and History: Eighteen Hundred and Froze To Death, The Year There Was No Summer". Islandnet.com. http://www.islandnet.com/~see/weather/history/1816.htm.

- ↑ American Beacon (Norfolk, Virginia), Vol. II, Issue 124 (July 4, 1816), 3.

- ↑ Sarah Snell Bryant diary, 1816 Remarks, original at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts; Samuel Griswold Goodrich, Recollections of a Lifetime (New York: Auburn, Miller, Orton, and Mulligan, 1857), 2: 78–79, quoted in Glendyne R. Wergland, One Shaker Life: Isaac Newton Youngs, 1793–1865 (Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 2006), chapter 2.

- ↑ Edward Holyoke, journal, 1816, in Soon, W., and Yaskell, S.H., Year Without a Summer, Mercury, Vol. 32, No. 3, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, May/June 2003.

- ↑ Nicholas Bennet, Domestic Journal, May–September 1816, Western Reserve Historical Society ms. V: B-68, quoted in Wergland, One Shaker Life: Isaac Newton Youngs, 1793–1865, chapter 2.

- ↑ "When should sweet corn be harvested? | Mississippi State University Extension Service". http://extension.msstate.edu/content/when-should-sweet-corn-be-harvested.

- ↑ William G. Atkins, History of Hawley (West Cummington, Massachusetts (1887), p. 86.

- ↑ American Beacon (Norfolk, Virginia), September 9, 1816, p. 3.

- ↑ "Crops," American Beacon (Norfolk, Virginia), September 13, 1816, p. 3.

- ↑ Columbian Register (New Haven, Connecticut), July 27, 1816, p. 2.

- ↑ John Luther Ringwalt, Development of Transportation Systems in the United States, "Commencement of the Turnpike and Bridge Era", 1888: 27 notes that the very first artificial road was the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, 1792–1795, a single route of 62 miles; "it seems impossible to ascribe to the turnpike movement in the years before 1810 any significant improvement in the methods of land transportation in southern New England, or any considerable reduction in the cost of land carriage" (Percy Wells Bidwell, "Rural Economy in New England ", in Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences, 20 [1916: 317]).

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Hubbard, Zachary (April 30, 2019). "Paintings in the Year Without a Summer". Philologia 11 (1): 17. doi:10.21061/ph.173. ISSN 2372-1952. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334584078. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Zerefos, C. S.; Gerogiannis, V. T.; Balis, D.; Zerefos, S. C.; Kazantzidis, A. (April 16, 2007). "Atmospheric effects of volcanic eruptions as seen by famous artists and depicted in their paintings". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions 7 (2): 5145–5172. doi:10.5194/acpd-7-5145-2007. ISSN 1680-7375. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00296303/file/acp-7-4027-2007.pdf.

- ↑ "Brimstone and bicycles" (in en-US). January 29, 2005. https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg18524841-900-brimstone-and-bicycles/.

- ↑ Nettels, Curtis (1977) (in en-us). The Emergence of a National Economy. White Plains, New York: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-87332-096-4.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 "1816, the Year Without a Summer". In Our Time (radio series). BBC Radio 4. April 21, 2016. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b077j4yv.

- ↑ "Joseph Smith Jr. – Significant Events". Lds.org. http://www.lds.org/churchhistory/presidents/controllers/potcController.jsp?leader=1&topic=events.

- ↑ Marshall, Alan (January 24, 2020). "Did a volcanic eruption in Indonesia really lead to the creation of Frankenstein?" (in en-US). http://theconversation.com/did-a-volcanic-eruption-in-indonesia-really-lead-to-the-creation-of-frankenstein-130212.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 50.5 Shelley, Mary (1993). Frankenstein. Random House. pp. xv–xvi. ISBN 0-679-60059-0.

- ↑ Why Vampires Never Die. by Chuck Hogan and Guillermo del Toro, The New York Times, July 30, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2015

- ↑ Polidori, John William. "The Diary of Dr. John William Polidori". http://www.gutenberg.org/files/55017/55017-h/55017-h.htm.

- ↑ Byron, George Gordon Noel Byron, sixth Bar (December 5, 1816), McGann, Jerome J., ed., "301 Darkness", Lord Byron: The Complete Poetical Works (Oxford University Press) 4: pp. 41–460, doi:10.1093/oseo/instance.00072952, ISBN 978-0-19-812756-7.

- ↑ Post, John D. (1977). The last great subsistence crisis in the western world. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Pr. ISBN 978-0-8018-1850-9.

- ↑ Wood, C. A. (1992) The climatic effects of the 1783 Laki eruption, pp. 58–77 in C. R. Harrington (Ed.), The Year Without a Summer?. Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Canada.

Further reading

- Klingaman, William; Klingaman, Nicholas (2013). The Year Without Summer: 1816 and the Volcano that Darkened the World and Changed History. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0312676452. https://archive.org/details/yearwithoutsumme00will/page/338.

- Soon, Willie; Yaskell, Steven (June 2003). "Year Without a Summer". Mercury. http://www.astrosociety.org/pubs/mercury/32_03/summer.html.

- Wood, Gillen (2014). Tambora: the eruption that changed the world. Princeton University Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0691150543. Bibcode: 2014tetc.book.....W.

External links

- 1816, the Year Without a Summer on In Our Time at the BBC

|