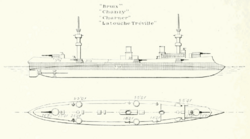

Engineering:Amiral Charner-class cruiser

| File:CharnerOriginal.tiff Amiral Charner at anchor, c. 1897

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Amiral Charner |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | missing name |

| Succeeded by: | missing name |

| Built: | 1894–96 |

| In commission: | 1895–1919 |

| Completed: | 4 |

| Lost: | 2 |

| Scrapped: | 2 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Armoured cruiser |

| Displacement: | 4,748 t (4,673 long tons) |

| Length: | 110.2 m (361 ft 7 in) |

| Beam: | 14.04 m (46 ft 1 in) |

| Draught: | 6.06 m (19 ft 11 in) |

| Installed power: | |

| Propulsion: | 2 screws; 2 × triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed: | 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) |

| Range: | 4,000 nmi (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 16 officers and 378 enlisted men |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: |

|

The Amiral Charner class was a group of four armoured cruisers built for the French Navy (Marine Navale) during the 1890s. They were designed to be smaller and cheaper than the preceding design while also serving as commerce raiders in times of war. Three of the ships were assigned to the International Squadron off the island of Crete during the 1897–1898 uprising there and the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 to protect French interests and citizens. With several exceptions the sister ships spent most of the first decade of the 20th century serving as training ships or in reserve. Bruix aided survivors of the devastating eruption of Mount Pelée on the island of Martinique in 1902. Chanzy was transferred to French Indochina in 1906 and ran aground off the Chinese coast in mid-1907. She proved impossible to refloat and was destroyed in place.

The three survivors escorted troop convoys from French North Africa to France for several months after the beginning of World War I in August 1914. Unlike her sisters, Bruix was transferred to the Atlantic to support Allied operations against the German colony of Kamerun in September 1914 while Amiral Charner and Latouche-Tréville were assigned to the Eastern Mediterranean, where they blockaded the Ottoman-controlled coast, and supported Allied operations. Amiral Charner was sunk in early 1916 by a German submarine. Latouche-Tréville became a training ship in late 1917 and was decommissioned in 1919. Bruix was decommissioned in Greece at the beginning of 1918 and recommissioned after the end of the war in November for service in the Black Sea against the Bolsheviks. She returned home in 1919 and was sold for scrap in 1921. Latouche-Tréville followed her to the breakers five years later.

Design and description

The Amiral Charner-class ships were designed to be smaller and cheaper than the preceding armored cruiser design, the missing name. Like the older ship, they were intended to fill the commerce-raiding strategy of the Jeune École.[1]

The ships measured 106.12 metres (348 ft 2 in) between perpendiculars and had a beam of 14.04 metres (46 ft 1 in). They had a forward draught of 5.55 metres (18 ft 3 in) and drew 6.06 metres (19 ft 11 in) aft. The Amiral Charner class displaced 4,748 tonnes (4,673 long tons) at normal load and 4,990 tonnes (4,910 long tons) at deep load. They were fitted with a prominent plough-shaped ram at the bow. This made the ships very wet forward, although they were generally felt to be reasonably good sea boats and handled well by their captains. Their metacentric height was deemed to be inadequate and all of the surviving ships had their military masts replaced by lighter pole masts between 1910 and 1914.[2]

The Amiral Charner-class ships had two horizontal triple-expansion steam engines, each driving a single propeller shaft. Steam for the engines was provided by 16 Belleville boilers at a working pressure of 17 kg/cm2 (1,667 kPa; 242 psi) and the engines were rated at a total of 8,300 metric horsepower (6,100 kW) using forced draught. The engines in Bruix were more powerful than those of her sister ships and were rated at 9,000 metric horsepower (6,600 kW). The ships had a designed speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph), but during sea trials they failed to meet their specified speed, only reaching maximum speeds of 18.16 to 18.4 knots (33.63 to 34.08 km/h; 20.90 to 21.17 mph) from 8,276 to 9,107 metric horsepower (6,087 to 6,698 kW). They carried up to 535 tonnes (527 long tons) of coal and could steam for 4,000 nautical miles (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[3]

Armament

The ships of the Amiral Charner class had a main armament that consisted of two 45-calibre Canon de 194 mm Modèle 1887 guns that were mounted in single gun turrets, one each fore and aft of the superstructure. The turrets were hydraulically operated in all ships except on Latouche-Tréville, whose turrets were electrically powered.[4] The guns fired 75–90.3-kilogram (165–199 lb) shells at muzzle velocities ranging from 770 to 800 metres per second (2,500 to 2,600 ft/s).[5]

Their secondary armament comprised six 45-calibre Canon de 138.6 mm Modèle 1887 guns, each in single gun turrets on each broadside.[6] Their 30–35-kilogram (66–77 lb) shells were fired at muzzle velocities of 730 to 770 metres per second (2,400 to 2,500 ft/s).[7] For close-range anti-torpedo boat defense, they carried four quick-firing (QF) 65-millimetre (2.6 in) guns, four QF 47-millimetre (1.9 in) and eight QF 37-millimetre (1.5 in) five-barreled revolving Hotchkiss guns. They were also armed with four 450-millimetre (17.7 in) pivoting torpedo tubes; two mounted on each broadside above water.[6]

Protection

The side of the Amiral Charner class was generally protected by 92 millimetres (3.6 in) of steel armor, from 1.3 metres (4 ft 3 in) below the waterline to 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) above it. The bottom 20 centimetres (7.9 in) tapered in thickness and the armor at the ends of the ships thinned to 60 millimetres (2.4 in). The curved protective deck of mild steel had a thickness of 40 millimetres (1.6 in) along its centerline that increased to 50 millimetres (2.0 in) at its outer edges. Protecting the boiler rooms, engine rooms, and magazines below it was a thin splinter deck. A watertight internal cofferdam, filled with cellulose, ran the length of the ship from the protective deck[8] to a height of 1.2 metres (4 ft) above the waterline.[9] Below the protective deck the ship was divided by 13 watertight transverse bulkheads with five more above it. The ship's conning tower and turrets were protected by 92 millimeters of armor.[8]

Ships

| Name | Builder[9] | Laid down | Launched | Commissioned | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| missing name | Arsenal de Rochefort | 15 June 1889[10] | 18 March 1893[10] | 26 August 1895[10] | Sunk by Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist., 8 February 1916[9] |

| missing name | 9 November 1891[11] | 2 August 1894[11] | 1 December 1896[11] | Sold for scrap, 21 June 1921[12] | |

| missing name | Chantiers et Ateliers de la Gironde, Bordeaux | January 1890[13] | 24 January 1894[13] | 20 July 1895[13] | Wrecked, 30 May 1907[9] |

| missing name | Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée, Granville | 26 April 1890[14] | 5 November 1892[14] | 6 May 1895[14] | Sold for scrap, 1926[15] |

Service

Amiral Charner spent most of her career in the Mediterranean, although she was sent to China during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900–01. Together with her sisters, Chanzy and Latouche-Tréville, the ship was assigned to the International Squadron off the island of Crete during the 1897-1898 upring there and the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 to protect French interests and citizens. With the exception of Bruix, the sisters spent most of the first decade of the 20th century as training ships or in reserve. Bruix served in the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean, and in the Far East before World War I. In 1902 she aided survivors of the devastating eruption of Mount Pelée on the island of Martinique and spent several years as guardship at Crete, protecting French interests in the region in the early 1910s. Chanzy was transferred to French Indochina in 1906. She ran aground off the Chinese coast in mid-1907, where she proved impossible to refloat and was destroyed in place after her crew was rescued without loss.[16]

The surviving ships escorted troop convoys from French North Africa to France for several months after the beginning of World War I in August 1914. Amiral Charner and Latouche-Tréville were then assigned to the Eastern Mediterranean where they blockaded the Ottoman-controlled coast and supported Allied operations. During this time, Amiral Charner helped to rescue several thousand Armenians from Syria during the Armenian genocide of 1915. She was sunk in early 1916 by a German submarine, with only a single survivor rescued. Latouche-Tréville was lightly damaged in 1915 by an Ottoman shell while providing naval gunfire support during the Gallipoli Campaign. Unlike her sisters, Bruix was transferred to the Atlantic to support Allied operations against the German colony of Kamerun in September 1914. She was briefly assigned to support Allied operations in the Dardanelles in early 1915 before she began patrolling the Aegean Sea and Greek territorial waters.[17]

Latouche-Tréville became a training ship in late 1917 and was decommissioned in 1919. Bruix was decommissioned in Greece at the beginning of 1918 and recommissioned after the end of the war in November for service in the Black Sea against the Bolsheviks. She returned home later in 1919 and was reduced to reserve before she was sold for scrap in 1921. Latouche-Tréville was stricken from the navy list in 1920 and was sold for scrap in 1926.[18]

Notes

- ↑ Feron, pp. 8–9

- ↑ Feron, pp. 10, 15, 17

- ↑ Feron, pp. 15, 17, 19, 25

- ↑ Feron, pp. 14–15

- ↑ Friedman, p. 218

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Feron, pp. 11, 15

- ↑ Friedman, p. 223

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Feron, pp. 12, 15

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 304

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Feron, p. 17

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Silverstone, p. 92

- ↑ Feron, p. 28

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Feron, p. 23

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Feron, p. 19

- ↑ Feron, p. 22

- ↑ Feron, pp. 18, 20–21, 24–25, 27

- ↑ Feron, pp. 19, 21–22, 28

- ↑ Feron, pp. 22, 28

Bibliography

- Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4. https://archive.org/details/conwaysallworlds0000unse_l2e2.

- Feron, Luc (2014). "The Armoured Cruisers of the Amiral Charner Class". in Jordan, John. Warship 2014. London: Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-236-8.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations: An Illustrated Directory. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Johnson, Harold; Roche, Jean P. (2006). "Question 22/05: French Amiral Charner Class Cruiser Differences". Warship International XLIII (3): 243–245. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Jordan, John; Caresse, Philippe (2019). French Armoured Cruisers 1887–1932. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4118-9.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

Template:Amiral Charner-class cruiser Template:WWI French ships

|