Engineering:Atari 800

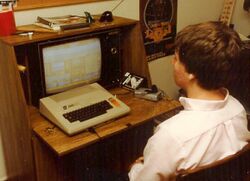

The Atari 800 is a home computer manufactured by Atari, based on the 6502 microprocessor which, shortly after its release in November 1979, was considered a milestone in the history of home computers. Its user-friendly design and robust construction made it easy for inexperienced users to get started with computer technology, which until then had been the preserve of specialists.[1]

The Atari 800 was offered initially in the US mail order business from the end of 1979—the department store chain Sears received the first versions in November 1979. At a price of $899, it was advertised as a "timeless computer" because of its expansion capabilities and future proofing. After various collaborations in the education sector initiated by Atari, the release of box-office hits like Star Raiders, and the expansion of the Atari dealer network, the company succeeded in raising its visibility steadily. Expansion into Europe boosted sales from mid-1981, which culminated in Atari's market leadership until the end of 1982.

Production of the Atari 800 was discontinued in mid-1983, around the same time that the Atari 600XL and Atari 800XL models were announced. Including stock sales that lasted until about the beginning of 1985, a total of about two million units of the two computer models Atari 400 and 800 were sold. The Guardian called it one of the 20 greatest home computers of all times in September 2020.[2] PC Magazine called it "as a killer next-gen game console with superior graphics and sound capabilities at the time of its release."[3]

History

While in the final stages of development for the Atari 2600 video game console, Atari began planning for a successor model in early 1977. The engineers' efforts were focused mainly on expanding the graphics capabilities of the highly integrated special circuit Television Interface Adapter (TIA) built into the Atari 2600. The improvements promised more sophisticated games while reducing the development effort.[1]

Development and prototypes

A still hand-wired early prototype of the Alphanumeric Television Interface Controller (ANTIC) was soon presented to Atari management. Following feasibility studies with other electronic components, Atari realised the new product could be more than a games console. For example, an integrated keyboard could be used for programming and device control for data transfer. These improvements seemed both technically and economically feasible.[1]

At that time, a modular design and the ability to program were reserved for expensive computers from IBM or Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) used in industry and research and, with clear cutbacks, for the much cheaper home computers like the Altair 8800, the TRS-80, the PET 2001 and the Apple II. However, the Apple II in particular suffered from awkward operation and unreliable technology and, compared to the latest generation of game consoles at the time, home computers were relatively expensive. This left out technically unsophisticated but open-minded interest groups with a small budget from the market. With this target group in mind, Atari quickly discarded the original plans for a new games console based on the ANTIC favouring their own, inexpensive and conceptually novel home computer. It had to be simple and safe even for beginners, and the device had to operate with commercially available televisions without detailed technical knowledge. Additionally, it had to be able to load games and application programs quickly and conveniently, similar to the plug-in modules familiar from game consoles.[1][4]

Low manufacturing costs were important as well as usability. Compatibility with the Atari 2600 console games was asked for, but rejected early in development. The system's technical key points were then presented by the main developers and approved by management in August 1977. This led to increased development funding, and the project was given the internal code name Colleen.[5]

Project Colleen

As work progressed, those responsible split the project into two models: a heavily stripped-down variant mainly for entertainment, and an application-oriented device with a typewriter keyboard and expansion possibilities. Development work for the first variant was spun off in November into a separate project called Candy—later to become the Atari 400—and that for the high-end device continued under the name Colleen.[6] The names Candy and Colleen were originally taken from two secretaries working in the back-office.[7]

Initial designs included 4 kilobytes (KB) of random access memory (RAM), two plug-in module bays, a parallel interface for peripherals, a keyboard and various expansion options. After the design of the ANTIC was completed in January 1978, further efforts were concentrated on completing special components—Color Television Interface Adapter (CTIA) and Potentiometer and Keyboard Integrated Circuit (POKEY).[8] The development work on these, which were available as hand-wired plug-in boards, dragged on until the end of March and cost over $10 million US (equivalent to $48,209,184 in 2024).[9] The development of the special components was completed in January 1978.[10]

Cromenco's Z-2 computer system was used to tune the special components to the MOS Technology 6502 processor. By mid-June, development of the circuit boards was complete; final work, mainly on the keyboard, was finished in August. The computer's external appearance had already been determined by the end of April, and a short time later the housing, together with integrated electromagnetic shielding, had been completed.[11]

Alongside the remaining work on some mechanical components, Atari looked into the availability of higher programming languages. The company decided on BASIC, a beginner-friendly language with which the new computer system could be programmed for the user's own purposes. An in-house development by Atari was ruled out because of a lack of capacity within a six-month deadline. Atari rejected the popular Microsoft BASIC because of its technical requirements. Instead, Shepardson Microsystems, Inc. was asked to create its own BASIC dialect, specially tailored to the Atari computers, at the beginning of October 1978.[12]

Renaming to Atari 800

In November 1978, after deciding to configure the computer with the market-standard 8K RAM, Atari changed the unofficial name Colleen to the official Atari 800, which was based on the memory size. The double zero following the number 8 classifies the computer as the basic device of the peripherals belonging to it. On 6 December 1978, the home computer project with its two devices, Atari 400 and Atari 800, was announced to the public in an article in the high-circulation The New York Times .[13]

Atari provided a first glimpse of its new product line to prospective customers in January 1979 at the Winter Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas.[14] The Atari 800 was on display together with the matching Atari 810 floppy disk drive and the Atari 820 printer. The Atari 800 was available to a larger audience for the first time in May at the 4th West Coast Computer Faire in San Francisco .[15] At the Summer CES in Chicago , the suggested retail price was announced as $1000.[16]

In June, final work was completed, and it passed the acceptance test for electromagnetic compatibility by the US Federal Communications Commission in August—a decisive prerequisite for to sell the device in North America.[17] Development had so far cost about $100 million US (equivalent to $482,091,837 in 2024); production moved to Atari's factory in Sunnyvale, California. However, it could not begin until October 1979, as the rapidly growing home computer industry suffered from a persistent shortage of parts from late summer.[18][19]

Market launch as a bundled offering

Some time before the launch, the manufacturer touted its Atari 800 as a "Timeless Computer", alluding to its expandability and long-lasting usability,[20] suitable for beginners and specialists alike ("[...] can be used by people with no previous computer experience, although it does not compromise capability for the sophisticated user").[21]

The Atari 800 was first offered in November 1979 as part of a marketing test[22] both in the Christmas edition of the mail-order catalogue and in the photo departments of some Sears Roebuck shops.[23][24] As well as the computer and power supply and instructions, the buyer received an Atari 410 programme recorder and other accessories for $999.99.[10] These included the basic equipment for the Educational System and BASIC, as plug-in modules together with the corresponding instruction material.[21] Shortly after the start of sales, Atari began to offer the Atari 410.[25][clarification needed]

Atari then began presenting its devices and associated entertainment software such as the game Star Raiders at trade fairs. That and general advertising opened up new distribution channels.[26][27] From the second quarter of 1980, further long-term planned advertising campaigns accompanied the presentations.[28] After increasing the price to $1,080, on 1 June 1980, Atari changed the marketing strategy away from bundled offers to individual devices. The programme recorder and educational system were no longer included, but the factory-installed RAM was increased to 16 KB.[29]

From mid-1980, the popularity of Atari computers had increased so much that third-party manufacturers also saw promising sales potential for both hardware and software.[30][31]

Education sector

As well as making a computer for entertainment, Atari wanted to put home computers in North American educational institutions, an area previously dominated by the Apple II and Commodore PET. The company thought students would use the same computers at home as they did at school.[32] In addition to special sales conditions for the education sector,[33] the matching software had also been launched early on with the Talk & Teach Cassette Courseware series.[34] In addition, from mid-1980[35] Atari relied increasingly on cooperation with the IBM-affiliated Science Research Associates, which was dedicated to promoting computer-aid teaching and took over distribution for Atari in this sector. As part of this cooperation, IBM gave a free Atari 400 with every Atari 800 bought by an educational institution from primary school to university.[36] Atari launched a similar promotion for schools a little later with three for two deals: With the purchase of two Atari 800 or Atari 400 computers, the buyer received an additional free Atari 400.[37]

The combined sales figures given for 1979 and 1980 for the Atari 400 and Atari 800 models vary between 50,000[38] and 300,000[39] units. Sales for 1980 alone were about $20 million U.S.[40]

Mass marketing

By the first half of 1981, Atari computers were established as permanent fixtures in the home computer market, which had been dominated by Tandy, Apple and Commodore, despite permanent delivery problems and some technical issues with accessories.[41][42][43] The sales achieved by Atari's computer division were $10 million in mid-1981, but this was counterbalanced by a similar tally of losses caused by production delays.[44] In April, Atari increased management personnel to cope with increasing demand and to implement the planned worldwide marketing.[45] The company introduced individually selectable expansion packages for its computers, specially tailored for the technically uninitiated.[46] These "Starter Kits" each contained coordinated, ready-to-connect hardware and software for programming (Atari Programmer), entertainment (Atari Entertainer), education (Atari Educator) and networking (Atari Communicator).[40][47] By August 1981, sales had increased to $13 million, reaching profitability for the first time.[38]

As well as expanding the hardware sector, Atari invested in further training of customer service personnel and authorised dealers,[43] as well as software support for the home market. This included the almost monthly releases of new in-house programs and games, the long-awaited publication of technical documentation by third-party manufacturers[48] and support for independent program authors. The latter included the organization of open programming competitions with correspondingly high prizes,[49] technical training in Atari's Acquisition Centres and starting the publishing platform Atari Program Exchange (APX). By founding APX, Atari made it possible for software producers, who were often completely inexperienced in business management, to distribute their programs through the Atari dealer network, which was by then fully developed in North America.[50]

International sales

After its American sales successes, Atari launched into the European market in the summer of 1981. As in the US, the release in Great Britain (£645,[51] equivalent to $2,490 in 2023), Italy (₤1,980,000) and the Benelux countries was accompanied by advertising in print and presentations at special exhibitions.[52] In France, on the other hand, sales (7500 F today)[53] did not begin until September 1982, because of time-consuming hardware adaptations to the SECAM television standard.[54]

In West Germany, Atari Elektronik Vertriebsgesellschaft mbH, which had already been responsible for marketing the Atari 2600 since 1980, took over sales and customer service from August 1981. The marketing of the "private computers", as Atari Germany officially called the 800, required considerable investment, especially for advertising, sales training and service activities. As with the promotional efforts in the video game sector, Atari placed corresponding advertisements in print media.[55] In addition to mail-order sales and specialist shops, the computers were also available in larger department store chains like Horten and Karstadt.[56] The recommended retail price of the Atari 800 with 16 KB RAM was 2995 DM, the floppy disk drive Atari 810 cost under 2000 DM and the BASIC plug-in module could be purchased for 272 DM.[57] Before the official sales launch, Telectron GmbH had already offered the US version of the Atari 800 with 8 KB RAM for 4200 DM in 1980.[58]

During the international expansion phase, Atari reacted to the ever-worsening competitive situation, especially in North America, with technical revisions of its computers. These included a revised operating system for new devices ("OS Version B")[59] and a bug-fixed version of the BASIC programming language.[60] In 1981, according to its figures, Atari sold about 300,000 home computers,[61] which meant they had established themselves as a mass-producer of goods allowed them to rise to become the US market leader.[62]

Price wars and market leadership

The introduction of various low-cost computers like the Sinclair ZX81 led Atari to offer substantial price reductions. A first discount of 16 percent was applied in January 1982, which lowered the retail price of the Atari 800 to $899. Also, delivery was in silver-coloured glossy packaging, which had been introduced for the Atari 400 a year earlier.[63] Commodore's aggressive pricing policy had an effect in West Germany: Atari Germany was forced to reduce the price from 2995 to 1995 DM in August 1982.[64]

From early autumn 1982, believed to be because of a price war started by Texas Instruments in the American home computer market,[65] Atari stopped further direct price reductions and switched to discount campaigns accompanying purchases: When purchasing Atari's hardware and software, "software coupons" enabled buyers to save up to $60 on many products from their programme range.[66] Also, buyers of the Atari 800 received two free additional 16 KB memory expansions October onwards, which meant that Atari effectively only offered the computer in the highest expansion stage with 48 KB RAM. Parallel to its discount campaigns, Atari expanded its customer service during 1982, especially in North America.[67] The Atari Service Centres set up nationwide in the USA took over consulting and repair services from then on, but also the conversion of older computers to the new GTIA graphics module and the revised operating system.[68] This made possible profitable sales by large retail chains such as J. C. Penney, Kmart and Toys R Us, which Atari's company management was striving for but were unable to offer any advice or warranty services because of a lack of qualified personnel.[69][70] This sales policy, now mainly geared towards mass marketing, brought Atari close to 600,000 home computer sales during 1982, of which the Atari 800 alone accounted for about 200,000 units.[71] With about 1.2 million units of the 400 and 800 models sold, Atari could successfully defend its market leadership.[72][73]

Despite Atari's world market dominating position, only about 2000 Atari 800 computers were sold in West Germany during 1982.[74] Due to the sales problems and the associated high price pressure, Atari Germany's investments paid off only sluggishly, and the home computer division gradually developed into the unloved "stepchild" of the national video game market leader.[75][76]

Announcement of successors and sell-outs

In March 1983, Atari released a successor model, the Atari 1200XL, with contemporary 64 KB RAM and a new case design. However, due to a lack of compatibility with its predecessors, it was unsuccessful and only had a short release period in the US.[77] Sales of the Atari 800 soared to unexpected heights, as its price had been lowered to $500 with the introduction of the new device, and it also raised no fears of program incompatibilities.[78]

With the announcement of the official successor, the Atari 800XL, at the Summer CES in Chicago,[79] and stopping production of the 800 in August,[80] the price drop accelerated; finally, in September 1983, the units were offered for $165.[81] Atari sold about 2 million units of the 400 and 800 models combined.[82]

Modern replicas

The manageable architecture of the system and extensive documentation from the manufacturer allow miniaturised replication of the electronics of the Atari 800 and compatible models with today's technical means at a manageable cost. Such a modern realisation first took place in 2014—as with other home computer systems—as an implementation on a programmable logic circuit (Field-programmable gate array (FPGA) together with an embedding system. The replica using FPGA technology was initially intended merely as a technical feasibility study, but in retrospect it also proved its practical utility: miniaturisation and the possibility of battery operation make it an easily stowable, reliably operating and transportable alternative to the original low-impact technology.[83]

Technical data

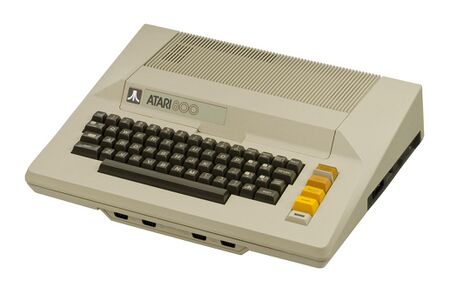

The Atari 800 case contains a total of three circuit boards and a sturdy cast aluminium housing to shield the electromagnetic interference fields caused by the computer.[84]

The main components of the largest board are the special POKEY component and the input/output modules together with peripheral connections. In addition, it provides slots for the smaller boards as component carriers. These contain the processor module with 6502 CPU (Central Processing Unit) together with the special components GTIA and ANTIC and the modules for voltage regulation plus television signal generation. The read-only memory (ROM) and the main memory are accommodated in the expansion slot in the form of plug-in cards.[85] In addition to the computer, the basic equipment included an external power supply unit, an antenna cable and antenna switch box and the operating instructions for the unit.[86][87]

Main processor

The Atari 800 is based on the 8-bit microprocessor MOS 6502, which was often used in contemporary computers.[88] The CPU can access an address space of 65536 bytes, which also sets the theoretically possible upper limit of 64 KB of RAM. The system clock is 1.77 MHz for PAL devices, but 1.79 MHz for those with NTSC output.[88][89][87]

Special modules for generating graphics and sound

Essential parts of the Atari 800's architecture are the three special components developed by Atari: Alphanumeric Television Interface Controller (ANTIC), Graphic Television Interface Adapter (GTIA) with its predecessor Color Television Interface Adapter (CTIA) and Potentiometer And Keyboard Integrated Circuit (POKEY).[90] They are functionally designed in such a way that they can be used flexibly within their task area and relieve the CPU.[89]

The two graphics modules ANTIC and CTIA/GTIA generate the image displayed on the television or monitor. For this purpose, the operating system or the user must first store corresponding data in the form of the "Display List" in the working memory. Among other things, the CTIA/GTIA allows the integration of a maximum of eight independent but monochrome graphic objects, the sprites. These objects, also called "players" and "missiles" in Atari jargon, are copied into the background image generated by the ANTIC according to user-definable overlapping rules and subjected to a collision check. This determines whether the sprites touch each other or certain parts of the background image ("playfield"). These capabilities were developed—as seen from the names "Playfield", "Player" and "Missiles"—to simplify the creation of games with interacting graphic objects and fast game play.[91][87] The capabilities of the two special modules ANTIC and CTIA/GTIA taken together give the display possibilities of the Atari computers a flexibility unrivalled by other home computers of the time.[92] The third special module POKEY contains further electronic components. These essentially concern the sound generation for each of the four sound channels, the keyboard query and the operation of the serial interface Serial Input Output (SIO) for the communication of the computer with corresponding peripheral devices.[93]

Due to their highly integrated design (LSI), the special components combine many electronic components in themselves and thus reduce the number of components needed in the computer, which results in a considerable saving of costs and space. Not least because their construction plans were never published, the Atari 800 could not be copied economically with the technology of the time, thus ruling out the illegal copying, which was quite common in the home computer industry.[94] The screen standards PAL, NTS, NTSI and NTSI were not used in the Atari 800.[95]

The PAL, NTSC and SECAM screen standards are realised by different external electronic circuits of the CPU, appropriately modified special components ANTIC (NTSC version with part number C012296, PAL version with C014887) and GTIA (NTSC version with part number C014805, PAL version with C014889, SECAM version with C020120) as well as different versions of the operating system adapted to them.[96][97]

| Graphic Level | Display Mode | Resolution (Pixel) | Colours | Memory (Bytes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | normal Text | 40 × 24 | 2 | 992 |

| 1 | Large text | 20 × 24 | 5 | 672 |

| 2 | 20 × 12 | 5 | 420 | |

| 3 | Point graphic | 40 × 24 | 4 | 432 |

| 4 | 80 × 48 | 2 | 696 | |

| 5 | 4 | 1176 | ||

| 6 | 160 × 96 | 2 | 2184 | |

| 7 | 4 | 8138 | ||

| 8 | 320 × 192 | 2 | ||

| 9 | GTIA-Modi | 80 × 192 | 16 | |

| 10 | 9 | |||

| 11 | 16 |

Memory and memory partitioning

The address space accessible by the CPU and ANTIC segments into different sections of different sizes on the Atari 800. For practical reasons, it is common to use hexadecimal notation for their addresses instead of decimal. It is usually preceded by a $ symbol to make it easier to distinguish. The addresses from 0 to 65535 in decimal notation correspond to the addresses $0000 to $FFFF in the hexadecimal system.[99]

The 32 KB range from $0000 to $7FFF is exclusively for working memory and in the smallest expansion stage of the Atari 800 is equipped with 16 KB RAM. Beyond that, extensions up to 48 KB, for example, are possible, whereby the occupied memory addresses then extend to $BFFF. After inserting a plug-in module, the 8 KB area in the middle of the RAM segment from $8000 to $9FFF is switched off and the ROMs in the plug-in module are inserted there. This means that when using plug-in module-based programmes such as Atari-BASIC, about 8 KB less working memory is available. The addresses of the special modules and other hardware components are located within a segment ranging from $D000 to $D7FF, immediately followed by the mathematical floating point routines ($D800 to $DFFF) and the operating system ($E000 to $FFFF). The area from $C000 to $CFFF is intended for system software to be added later by Atari, but can also be used by main memory or alternative operating system components.[99]

After switching on the computer, the CPU first reads out the contents of the ROM modules with the operating system, which initialises the Atari 800 together with connected peripheral devices. If no plug-in modules with executable contents are present, the so-called Memo Pad is started by the operating system. This is a rudimentary text input programme without further possibilities such as saving.[99]

Input and output interfaces

Connections to the outside world are through four controller sockets on the front of the housing, a RF Connector for the television, a slot for the exclusive use of ROM plug-in modules, and a socket of the proprietary serial interface (Serial Input Output, or SIO for short). The latter is used to operate appropriately equipped "intelligent" peripheral devices with identification numbers. A transmission protocol and connector system specially developed by Atari for this purpose is used. Printers, floppy drives and other devices with two SIO sockets can thus be "linked" with only one type of cable. One of the two sockets is used for communication between the device and the computer (serial bus input) and the remaining socket is used to connect and manage another device (serial bus extender).[100] The standard interfaces RS-232C (serial) and Centronics (parallel) used in many other contemporary computer systems are provided by the Atari 850 interface unit, which can be purchased separately.[101][102][103]

Peripheral Devices

The Atari 800 can operate all the peripherals released by Atari for the XL and XE series, which do not required the parallel bus of the XL and XE computers for connection. In the following, only those available from the end of 1979 to the end of 1983 are discussed.[104]

Mass storage

Western home computers of the 1980s used mainly cassette recorders and floppy disk drives data backup; in the professional environment, hard disk and removable disk drives were used for backup. The cheapest variant of data recording by compact cassettes generally has the disadvantage of low data transfer rates and thus long loading times, whereas the much faster and more reliable diskette and disk drives were much more expensive to purchase.[105] When the Atari 800 was released, it had cassette and, a little later, diskette and hard disk systems available for mass storage.[104]

Cassette systems

Unlike other contemporary home computers such as the TRS-80 or the Sinclair ZX81, the Atari 800 cannot be used with standard cassette recorders to store data. Instead, it requires a device adapted to its serial interface—the Atari-410 programme recorder. The average data transfer rate is 600 bits/s; there is room for 50 KB of data on a 30-minute cassette.[106] In addition, the Atari 410 has the special feature of a stereo sound head, which makes it possible to play music or spoken user instructions parallel to the reading process.[107] For reasons of cost and space saving, there is no loudspeaker built into the device; the audio signals are output via the SIO cable via POKEY on the television set. There is also no SIO socket built into the Atari 410 programme recorder, so it must always be connected as the last link in the chain of peripheral devices.[104]

-

Atari Computer Program Cassette

Floppy systems

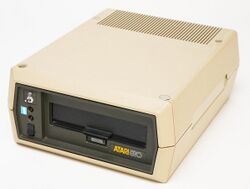

Together with the Atari 410 program recorder, a floppy disk drive adapted to Atari's SIO interface was also available shortly after the market introduction of Atari 400 and 800, the Atari 810 floppy station. With the Atari 810 floppy drive, 5¼" floppy disks can be written on one side in single write density with 720 sectors of 128 bytes each, allowing 90 KB of data to be stored per floppy disk side.[108] The average data transfer rate is about 6000 bits/s,[109] ten times what the Atari 410 data recorder is capable of transferring in the same time. During the entire production period, the manufacturer made several changes to the drives. For example, there are versions with partially faulty system software and those with different drive mechanics.[108]

In addition to the Disk Station 810, another device was available for a short time in North America in the form of the much more powerful Atari 815 disk drive.[110] It has two drive mechanisms, each also operating at double write density, allowing 180 KB of data to be stored per 5¼" disk side. Due to the complicated construction involved, only manual production was possible. Due to the resulting high price of 1500 US dollars and at the same time great susceptibility to errors, the device was taken out of the range by Atari after delivery of only small quantities amounting to about 60 units.[111]

From mid-1982 onwards, a large number of Atari-compatible disk drives appeared from various third-party manufacturers. These included devices of varying performance from Percom[112][113] drives with additional data track display from Rana[114] and also dual drives from Astra.[115]

Hard disk systems

Around the middle of 1982, the US company Corvus introduced 5¼" hard disk models with storage capacities of 5 to 20 MB for the Atari 800.[116] Unlike Atari's peripherals such as the 810 floppy disk drive, the connection is not made via the serial port. Rather, two of the four joystick sockets are misused by Corvus for data exchange with the hard disk drive by means of corresponding hardware and software.[117] By chaining up to four Corvus drives, a maximum storage capacity of 80 MB can be achieved. In addition to the significantly increased storage capacity, the hard disks offer a much shorter average access time and much greater reliability compared to the Atari 810 floppy disk drive, which enables more effective work. In addition, an extension called Corvus Multiplexer local network, which was sold separately by Corvus at the time, allows several Atari 800 computers to be connected to one and the same hard disk at the same time. This network capability was used, for example, by computer-aided teaching in various schools and larger mailboxes. The price of the cheapest Corvus drive, together with the required drive electronics and software, was US$3195 when it was launched.[118][119]

Due to the multiple copy protection mechanisms used at the time, only very few programs worked together with Corvus hard drives without additional modifications. The Integrator board, introduced by another third party in 1983, solved these difficulties and also allowed the hard disk drives to be used without first having to load their drive software from a floppy drive.[116]

Interface unit

Image output on the Atari 800 can be done on a monitor or via built-in RF modulator on a standard colour or black-and-white TV set.[120]

The thermal printer Atari 822 and the needle-based models Atari 820 and Atari 825 can be used to fix text and graphics in writing. Printers from other manufacturers can only be operated with the aid of additional devices, as the Atari 800 does not have the corresponding standard interfaces. This can be remedied by interposing an Atari 850 interface module, which can be used to operate RS-232 and Centronics printers from Epson, Mannesmann and others.[121] There are also third-party printers from other manufacturers.[120]

In addition, there is a wealth of output add-ons from third-party manufacturers: Starting with The Voicebox by The Alien Group,[122] which is intended for voice output, to 3D glasses that can be built by the user for viewing stereographic content on a TV set,[123] to the programmable robot gripper arm,[124]

Input devices

The typewriter keyboard of the Atari 800 contains a total of 56 individual keys, one space and four function keys. As an extension to the keyboard, Atari offered an external numeric keypad called CX85 for simplified entry of digits for use with various application programs such as spreadsheets or accounting programs.[125][126][127]

-

Atari CX65 Keyboard Block

-

Atari Joystick CX40

-

Joystick Competition Pro

-

Atari 2600 Paddle Controller

All other input devices, like the numeric keypad, are connected to one or more of the four controller sockets on the front of the computer case. These include joysticks[128] from a wide variety of manufacturers, paddle controllers, special small keyboards,[129] the trackball controller from TG Products[130] and graphics tablets from Kurta Corporation[131] and Koala Technologies Corp.[132]

Extensions

The Atari 800 was designed from the outset as an expandable system. For this purpose, an easily accessible expansion slot with a total of four slots is available,; one of the slots is permanently occupied by the card with the operating system. The remaining three allow for memory upgrades or 80-character cards.

Working memory

With the initially installed working memory of 8 KB, little more than playing games was possible, because with BASIC, the memory space is insufficient for the integration of the highest-resolution graphics level. If a floppy disk drive is used to load and save the BASIC programmes created, the capacity limit is quickly reached with the 16 KB RAM supplied later. The reason for this is the memory-intensive diskette operating system (DOS) takes up a large part of the RAM in addition to the user's BASIC programme. With the Atari 800, however, the easily accessible expansion slots and the cards provided by Atari with a maximum of 16 KB RAM can be easily upgraded to a comfortable 48 KB of working memory.[133][134]

The disadvantage of the maximum memory expansion with only 16 KB plug-in cards is the associated complete occupation of the expansion slot. This means that no further slots are available for 80-character cards, for example. For this reason, third-party manufacturers such as Mosaic[135] and Axlon[136] brought the first 32-KB RAM cards onto the market at the beginning of 1981. At the end of 1981, models were added that provided up to 128 KB of RAM with the help of technical refinements (memory bank switching). These RAM disk systems emulated one or more floppy disk drives with a data transfer rate that could exceed that of the Atari 810 floppy disk drive by a factor of twenty.[137][138][139]

80-character cards

For a clearer and less tiring display of image content, the 80-character cards produced for the Atari 800 are used. Because of the high horizontal resolution of 560 pixels, these are unsuitable for use with a television but require appropriate computer monitors.[140] The Full-View 80 card, released by the company Bit3 at the end of 1982, is placed in the last of the expansion bays. The 80-character mode can be activated by a command call, whereby ANTIC and GTIA are switched off and the graphics processor Synertek 6545A-1[141] located on the plug-in card takes over the image generation. The corresponding software is contained in the read-only memory of the plug-in card,[142] in contrast to the Austin-80 Video Processor expansion released later by Austin Franklin Associates. Its control software is housed on a plug-in module intended for the right-hand slot.[143]

Software

As with other home computers of the 1980s, various data carriers distributed commercial software. However, the inexpensive compact cassettes, which were particularly popular with game manufacturers, were very susceptible to errors because of the heavy mechanical strain on the magnetic tape, and their use was often associated with long loading times. In addition, certain operating modes, such as relative addressing, which is advantageous for operating databases, are not possible with data cassettes. On the other hand, with plug-in modules, which were much more expensive to produce, the programmes they contained were available as soon as the computer was switched on, which was a great advantage, especially for system software and frequently used applications. The best compromise between loading time, possible operating modes, reliability and storage capacity was achieved by floppy disks, which were supported by the 810 disk drive when the Atari 800 was released.[144][145]

The range of programs for the Atari 800 computer included, in addition to the selection of commercial programs distributed by Atari and APX, software (listings) for typing developed by third-party manufacturers and published in magazines and books. The commercial programmes were offered on plug-in module, diskette and cassette.[145][146]

Of the software in circulation, illegal copies ("pirated copies") always made up a large proportion and often presented smaller software developers with existential economic difficulties. As a result, copy protection systems were increasingly used, especially for games as the best-selling software.[147]

Operating Systems

Initialisation and configuration of Atari 800 hardware falls under the remit of the Operating System (OS), which is housed in read-only memory. After numerous errors had become known, Atari published a bug-fixed version with OS-B in 1982. The subroutines of the 10 KB operating system control various system processes that can also be triggered by the user. These include the execution of input and output operations such as keyboard and joystick queries, floating point calculations (FLOPS), the processing of system programmes after interruptions (interrupts) and the provision of a screen driver to generate the various graphics modes.[148] The start addresses of the individual subroutines are combined in a jump table to maintain compatibility with later operating system revisions or new versions. To distinguish it from the operating system of the later XL and XE models, the OS of the Atari 400 is often referred to as Oldrunner.[149]

Programming languages and application programmes

The processing of user-specific tasks often requires specially tailored software solutions, the application programmes. If these do not exist or cannot be used for technical or economic reasons, suitable programming languages were used.

Assembly language

In the early 1980s, the creation of time-critical action games and in control engineering, for example, required optimal use of the hardware. In the home computer sector, this was only possible by using assembly language with corresponding translator programs, the assemblers. In many cases, assemblers were delivered with an associated editor for entering the program instructions ("source code"), often also as a programme package with debugger and disassembler for error analysis. In the professional developer environment, cross-assemblers were often used.

Shortly after the release of the Atari computers, only the slow assembler editor delivered on a plug-in module was available from Atari. It offered little comfort and could only be used for small projects. In contrast to other assemblers, however, it allowed saving the created source files and executable programs on cassette, which was an advantage especially for many Atari 800 users without a disk station and thus made them easily overlook the disadvantages. The assemblers needed for professional program development were not available until later with Synassembler (Synapse Software), Atari Macro Assembler (Atari), Macro Assembler Editor (Eastern Software House), Edit 6502 (LJK Enterprises) and the powerful MAC 65 (Optimized Systems Software).[150]

Interpreter high-level languages

Main Atari BASIC, BASIC A+ and Microsoft BASIC

BASIC published by Atari was accompanied by two others: Microsoft BASIC, which was the quasi-standard at the time, and a backwards-compatible product to Atari BASIC called BASIC A+ by Optimized System Software. BASIC A+ in particular contains extended editing possibilities, simplifications in the command structure, and it supplements many features not implemented in Atari and Microsoft BASIC. For example, these include convenient use of sprites ("player missiles graphics") through command words provided specifically for this purpose.[151][152] In contrast to the Atari 400, the Atari 800 allows simultaneous operation of two plug-in modules, each specially designed for the different slots. For example, with the help of the programme The Monkey Wrench II, the Atari BASIC can be extended by various commands.[153][154]

The basic limitations of the interpreter, such as the low execution speed and the large amount of memory required, have a negative effect on the usability of BASIC programmes. These disadvantages can be mitigated by special programmes—BASIC compilers. These create executable machine programmes that can be run without a BASIC interpreter and often allow faster execution. Various compilers are available for the Atari BASIC with ABC BASIC Compiler (Monarch Systems), Datasoft BASIC Compiler (Datasoft), and BASM (Computer Alliance).[155]

In addition to the programming language BASIC in its various dialects, the interpreter language Logo was available at the start of Atari 800 sales. Supported by elements such as turtle graphics, this provides a child-friendly and interactive introduction to the basics of programming. The programming language Atari PILOT, which was introduced later, has similar features. With QS-Forth (Quality Software), Extended fig-Forth (APX)[156] and Data-Soft Lisp (Datasoft)[157] further programming languages joined the range of products for the Atari 800.[158]

High-level compiler languages

As a middle ground between interpreter high-level language (slow in execution, but easily readable source codes and simple error analysis) and assembly language (difficult to learn and awkward to handle, but in the early 1980s no alternative for generating fast and memory-efficient programs), compiler high-level languages also established themselves in the home computer sector in the course of the 1980s. The execution speed of the machine programs created with them was much greater compared to interpreted programs such as the built-in BASIC, but did not quite reach that achieved by assemblers.

During the product's lifetime until the end of 1983, the only compiler language available to Atari 800 users was APX Pascal.[159]

Application software

In addition to programming languages for an individual to create their own applications, the range of programmes for the Atari computers includes only a small selection of ready-made commercial application software compared to its contemporary rival, the Apple II. Among the best-known application programs are VisiCalc (Visicorp, spreadsheet), The Home Accountant (Continental Software, accounting), Atari Writer (Atari, word processing), Bank Street Writer (Broderbund, word processing) and Letter Perfect (LJK Enterprises, word processing).[160]

In addition, the Atari 800 was also used for online applications, which included banking with the Pronto software[161] and the operation of mailboxes through various also self-written programs.[162] In addition, application software presumably developed in-house enabled it to be used as the official computer of the tennis organisation (ATP) Association of Tennis Professionals.[163] in the logistics area of the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz,[164] to generate stage sets for the German music group Kraftwerk[165] and as a simulation computer for training employees of a Californian marine research institute.[166] The Atari 800 could be also used as a computer for the production and distribution of music.[167][168]

Learning programmes

There are a large number of programmes that serve the computer-assisted imparting of teaching content and its subsequent interactive retrieval. The knowledge to be imparted is presented in a playful form, with a constantly increasing level of difficulty to keep the learner motivated. Great importance is attached to age-appropriate presentation, ranging from toddlers to students. For the youngest learners, animated stories with comic-like characters are often used as accompanying tutors; for adolescents, the teaching content to be queried is dressed up in adventure games or action-packed space adventures; in the higher-level teaching content for students and adults, on the other hand, lexically presented knowledge with subsequent quizzing and success reporting predominates. The learning areas covered by the software include reading and writing, foreign languages, mathematics, technology, music, geography, demography, typing schools and computer science. The best-known manufacturers include Atari, APX, Dorsett Educational Systems, Edufun, PDI and Spinnaker Software.[169]

Games

By far the largest type of Atari software, both commercial and freely available, are the games. The early shoot-'em-up games such as Star Raiders or the board game conversion 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe were joined only a year later by other action games, adventures and arcade conversions. Both professional producers and hobby programmers profited from Atari's publication of technical documentation, the programming instructions in computer magazines and books, and the powerful development tools that had emerged in the meantime. Among the published titles, however, were also many poor ports of, for example, Apple II games without the unmistakable "Atari look", namely a mixture of various "colourful" and soft-shifted graphics, supplemented by the typical POKEY music together with sound effects.[170]

Among the games released for the Atari computers are many that were already considered video game classics in the early 1980s: Star Raiders (probably 1979), Asteroids (1981) and Pac-Man (1982).[170] Many game designers of the time considered the 3D game Star Raiders to be a defining experience and reason to choose an Atari computer over, say, an Apple II or Commodore PET. Subsequent works such as Miner 2049er (Bill Hogue, Big Five Software, 1982), Eastern Front (1941) (Chris Crawford, APX, 1982), Capture the Flag (Paul Edelstein, Sirius Software, 1983), Archon (John Freemann, Electronic Arts, 1983) and M.U.L.E. (Daniel Bunten, Electronic Arts, 1983) are among the standout titles of their time and enabled software houses such as MicroProse and Electronic Arts, for example, to rise rapidly to become industry giants.[171] One of the most popular games for the Atari computer was Miner 2049er.[172]

Among the most popular games for the Atari computers, besides the Infocom adventures, are largely shoot-'em-up games such as Crossfire (Sierra On-Line, 1981) and Blue Max (Synapse Software, 1983), racing games such as Pole Position (Atari, 1983), war simulations such as Combat Leader (SSI, 1983), but also graphic adventure games such as Excalibur (APX, 1983) and Murder on the Zinderneuf (Electronic Arts, 1983).[173]

Magazines

In the 1980s, computer magazines played a major role for many home computer owners, alongside reference books. The issues, which were often published monthly, contained test reports on new products, programming instructions and software to type. They also served as an advertising and information platform as well as a means of establishing contact with like-minded people.

The English-language magazines Antic, A.N.A.L.O.G., Atari Connection and Atari Age dealt specifically with Atari home computers; occasional reports and programmes for the Atari computers were also published by the high-circulation Byte Magazine, Compute! and Creative Computing, among others. While the Atari 800 was on sale in Germany, information and programmes could be found in the magazines Chip, Happy Computer, P.M. Computermagazin, Computer Persönlich and Mein Home-Computer, among others.[174][175][176][177][178]

Emulation

After the end of the home computer era in the early 1990s, and with the advent of powerful and affordable computing technology in the late 1990s, dedicated enthusiasts increasingly developed programs to emulate home computers and their peripherals. With the help of emulators, a single modern system with data images of the corresponding home computer programmes was sufficient to play old classics of various home computer systems. The advent of emulators set in motion, among other things, an increased transfer of software that might otherwise have been lost to modern storage media, thus making an important contribution to the preservation of digital culture.[179] Powerful emulators for home computer systems are emulators for the Internet.

The most powerful emulators for Windows and Linux systems are considered to be Atari++, Atari800Win Plus, Mess32[180] and Altirra.[181]

Reception

Contemporary

North America

The release of the Atari 400 and 800 was universally well received. The high-circulation magazine Compute! wrote of a new generation of computers:

With the introduction of the Atari line of computers we are seeing a third generation of microcomputers - not just from the technical end but also from a marketing approach. - John Victor: Compute!, November/December 1979[182]

The same reviewers said the classification of the new devices is best described as a hybrid between a video game and a computer. They contained the best of both worlds, which made them a personal computer and home device in equal measure. These characteristics predestined the Atari 800 for learning and entertainment purposes.[182] However, since the best hardware was useless without the appropriate software to run it, Atari had learned from the competitions' mistakes and provided the user with the programming language Atari BASIC, a decidedly easy access to the colourful graphics and sound features of its devices. This marketing of coordinated hardware and software—including the extremely popular game Star Raiders,[183] which was directly tailored to the Atari 8-bit computers—was a novelty.[184]

Due to the modular concept, however, more connection cables would be needed than with the compact Commodore PET, for example, which could be a disadvantage under certain circumstances[185] as could the non-validating storage of programs on cassette.[186] From the summer of 1980, delivery problems and the lack of application-oriented software were criticised in particular, and Adam Osborne's computers were not predicted to have much of a future.[187]

When, contrary to Osborne's predictions, Atari computers nevertheless managed to establish themselves and even became the market leader, the trade press continued to recommend them mainly for price-conscious households:[188] Jerry Pournelle said in Byte in July 1982, "Atari has much better graphics, and just about everyone says that if you're only interested in games, that's the machine to get." stated [189]

Agreeing with the trade press, game writers such as David Fox (programmer at Lucasfilm games) and Scott Adams (founder of Adventure International) saw the Ataris as the most graphically and soundly capable machines in the entire home computer market:

User-definable character sets, player-missile graphics, fine scrolling, vertical-blank interrupts, and display-list interrupts can be combined with colour mapping to give the Atari a performance edge that will probably never be equalled (except by Atari). Custom fonts, player-missile graphics, fine shift, raster interrupt, and display-list interrupts can be combined with colour mapping to give the Atari a performance edge that probably will never be equalled (except by Atari itself)."[190]

Scott Adams wrote: The Atari is my personal favourite. In my opinion, it is the best micro[computer] currently available [...] I like the capabilities of this machine: mature technology with excellent graphics and sound capabilities, which is very well thought out and built. It's the Atari I use at home, too."[191] Over time, however, Atari's marketing concept came to be criticised for not supporting its capabilities as an application computer. Although the Atari computers had enjoyed a good reputation since their introduction as powerful personal computers, the focus of use for the devices had shifted to the home sector with special attention to the entertainment and education sector with the discontinuation of production of the powerful floppy disk drive Atari 815. In addition, there were mistakes in the choice of distribution channels. The shift of sales by large chain shops would have induced smaller specialised shops with the appropriate competence and services to remove Atari computers from their range because of a lack of competitiveness. This would have eliminated another important mainstay for supplying the computers with powerful application software, so that even the Atari 800 was ultimately perceived and bought only as a pure games console.[192]

German-speaking countries

Shortly after its release in Germany, the Atari 800 was characterised by Chip, the computer magazine with the largest circulation at the time, as a device for the advanced user "who, in addition to his hobby application, also bases his purchase decision on the professional sector". The stable device design, the graphic possibilities, the colour output, a detailed documentation, the already existing large program library together with various programming languages such as Atari PILOT and Atari Assembler were also positively emphasised.[193]

Retrospective

Shortly after its replacement by the technically hardly changed successor models 600XL and 800XL, the Atari 800 was said to be an excellent design that set a new standard in the home computer market. The fantastic graphics were reflected above all in the good games, one of the strengths of its strengths.[194] According to Michael P. Tomczyk[195] and Dietmar Eirich, one of the few points of criticism was the price, which was too high at the time of introduction:

Atari [...] brachte auch schon sehr früh die Heimcomputer Atari 400 und Atari 800 auf den Markt, die zwar solide und exzellente Geräte waren, leider aber in der Anfangsphase der Heimcomputer zu teuer.

(in english: "Atari [...] also launched the Atari 400 and Atari 800 home computers very early, which were solid and excellent devices, but unfortunately too expensive in the early stages of home computing.")

- Dietmar Eirich and Sabine Quinten-Eirich, 1984[196]

In retrospect, according to Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton, Atari understood for the first time how to combine the features of a pure gaming machine with the capabilities of home computers of the time while remaining easy to use. According to the two authors, one of the main reasons for the success of this demanding task was the experience of the Atari engineers who had already been involved in the construction of the successful VCS-2600 game console.[197] As a result, special electronic components were used for the first time in a home computer to relieve the main processor. Their graphical refinements in the form of the Player/Missile graphics, for example, were groundbreaking for later devices. The use of a special component also meant that the sound properties belonged to the highest quality category at the time, and the Atari 400 thus replaced the Apple II as the best gaming computer.[197][198] The Atari 400 was the first home computer to use special electronic components. The authors of the internet platform Gamasutra see the release of the game Star Raiders as the decisive reason for the popularity of Atari computers, which increased within a very short time: "Upon release, Star Raiders became the first 'killer app' of computer gaming. It was the first computer game that could be called a 'machine seller'."[199] For the permanent lack of powerful application software, Michael Tomczyk blames Atari's original and controversial practices regarding the publication of technical documentation:

"Unfortunately, Atari neutralized their own advantage. To everyone’s shock and dismay, they decided to keep secret vital technical information like memory maps and bus architectures which programmers needed to write software. They then tried to blackmail programmers by indicating that they could get technical information only if they signed up to write Atari-brand software. This alienated the fiercely independent hobbyist/programmer community, and as a result many serious programmers started writing software for other machines instead." – Michael P. Tomczyk, 1985

A later change in the restrictive information policy could not have helped to make up for the backlog that had already arisen. Thus, as time went on, mainly games for the Atari home computers were published, which meant that these were now more and more perceived as pure gaming machines:

Many customers thought the Atari 400 and 800 were more expensive versions of the Atari 2600 videogame machine. Some people even doubted whether the Atari 400 and 800 were real computers. – Michael P. Tomczyk, 1985

Due to the competition created by Atari itself with the in-house game console VCS 2600 and mainly as a result of emerging competition from Texas Instruments and Commodore with their extensive program libraries in the application area, the sales successes could not have been continued.[200] Decisive market shares would thus have again fallen to the Apple II and above all the newly released Commodore 64 from 1983 onwards.[201]

Literature

- Atari Inc.: Technical Reference Notes. 1982.

- Atari Inc.: Field Service Manual.

- Jamie Lending: Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation, Ziff Davis, 2017, ISBN 9780692851272

- Jeffrey Stanton, Robert P. Wells, Sandra Rochowansky, Michael Mellin: Atari Software 1984. The Book Company, 1984,ISBN 0-201-16454-X

- Julian Reschke, Andreas Wiethoff: Das Atari Profibuch. Sybex-Verlag GmbH, Düsseldorf, 1986, ISBN 3-88745-605-X

- Eichler, Grohmann: Atari 600XL/800XL Intern. Data Becker GmbH, 1984, ISBN 3-89011-053-3

- Marty Goldberg, Curt Vendel: Atari Inc. – Business is Fun. Syzygy Company Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-9855974-0-5

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Atari 800. |

- Atari++ Emulator for UNIX/Linux systems

- Altirra Emulator for Windows-Systems

- Xformer 10 Emulator for Windows 10

- AtariAge International forum for Atari 8-bit friends

- Michael Currents Webseite with many resources, including the frequently asked questions about Atari

Reference section

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Marty Goldberg, Curt Vendel: Atari Inc. Business is Fun. Syzygy Company Press, 2012, p. 446 f.

- ↑ Stuart, Keith (7 September 2020). "The 20 greatest home computers – ranked!" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/games/2020/sep/07/the-20-greatest-home-computers-ranked.

- ↑ "The Golden Age of Atari Home Computers" (in en). https://www.pcmag.com/news/the-golden-age-of-atari-home-computers.

- ↑ Compute’s First Book of Atari. Small System Services, Inc., 1981, P. 5.

- ↑ Bill Loguidice, Matt Barton: Vintage Game Consoles. Routledge Chapman & Hall, 2014, P. 56.

- ↑ Marty Goldberg, Curt Vendel: Atari Inc. Business is Fun. Syzygy Company Press, 2012, P. 452 f.

- ↑ Lendino, Jamie (16 March 2017). Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation. Ziff Davis. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-692-85127-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=DkaoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA15.

- ↑ Marty Goldberg, Curt Vendel: Atari Inc. Business is Fun. Syzygy Company Press, 2012, P. 454.

- ↑ "InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community" (in en). InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.. 17 August 1981. p. 43. https://books.google.com/books?id=pD0EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Lendino, Jamie (16 March 2017). Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation. Ziff Davis. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-692-85127-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=DkaoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA36. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ↑ Marty Goldberg, Curt Vendel: Atari Inc. Business is Fun. Syzygy Company Press, 2012, P. 457 ff.

- ↑ Bill Wilkinson, Kathleen O’Brien, Paul Laughton: The Atari BASIC Source Book. Compute! Books, 1983, P. 9 f.

- ↑ Schuyten, Peter J. (6 December 1978). "The Computering entering House". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1978/12/06/archives/technology-the-computer-entering-home.html?searchResultPosition=1.

- ↑ "InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community" (in en). InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.. 7 February 1979. pp. 1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ej4EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ "InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community" (in en). InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.. 11 June 1979. pp. 8. https://books.google.com/books?id=Gj4EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ Creative Computing Magazine (August 1979) Volume 05 Number 08. Creative Computing. August 1979. pp. 26. http://archive.org/details/creativecomputing-1979-08.

- ↑ "InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community" (in en). InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.. 13 August 1979. pp. 4. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ij4EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ "InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community" (in en). InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.. 26 July 1982. pp. 24. https://books.google.com/books?id=LjAEAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ Byte Magazine Volume 05 Number 03 - Computers in the Laboratory. McGraw Hill. 1980. p. 110. http://archive.org/details/byte-magazine-1980-03.

- ↑ Koyama, Junichiro (2007). "Title Unclear". Journal of Information Processing and Management 50 (3): 55. doi:10.1241/johokanri.50.144. ISSN 0021-7298. Bibcode: 2007JIPM...50..144K.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Introducing the Atari Personal Computer Systems". http://www.atarimania.com/documents/atari-400-800-launch-press-kit.pdf.

- ↑ "Printed Software Becomes a Reality". Byte Magazine Volume 05 Number 04 (McGraw Hill): 115. 1 April 1980. http://archive.org/details/byte-magazine-1980-04.

- ↑ "InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community" (in en). InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.. 18 February 1980. pp. 7. https://books.google.com/books?id=aj4EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ Lendino, Jamie (16 March 2017). Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation. Ziff Davis. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-692-85127-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=DkaoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA36. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ↑ Lendino, Jamie (16 March 2017). Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation. Ziff Davis. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-692-85127-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=DkaoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA15.

- ↑ "InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community" (in en). InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.. 13 October 1980. p. 38. https://books.google.com/books?id=Pj4EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ Compute! Magazine Issue 003. Small System Services. 1980. p. 4. http://archive.org/details/1980-03-compute-magazine.

- ↑ Tomczyk, Michael M. (1980). "Atari's Marketing Vice President Profiles The Personal Computer Market". Compute! (Small System Services): 17. http://archive.org/details/1980-07-compute-magazine.

- ↑ Robert, Lock (1980). "A host of new peripherals.". Compute! (Small System Services): 4. http://archive.org/details/1980-07-compute-magazine.

- ↑ Lock, Robert (July 1980). "The Atari Gazette". Compute! (Small System Services): 58. http://archive.org/details/1980-07-compute-magazine.

- ↑ Blank, George (September 1980). "Image Computer Products". Creative Computing Magazine (Creative Computing): 182. http://archive.org/details/creativecomputing-1980-09.

- ↑ Libes, Sol (March 1983). "Battle in the Classroom". Byte (McGraw Hill): 495. http://archive.org/details/byte-magazine-1983-03.

- ↑ Brenda, Laurel (March 1981). "The Renaissance Kid.". Atari Magazine (Atari, Inc.): 15. http://archive.org/details/Atari_Connection_Volume_1_Number_1_1981-03_Atari_US.

- ↑ Blank, George (September 1980). "Image Computer Products". Creative Computing Magazine (Creative Computing): 180. http://archive.org/details/creativecomputing-1980-09.

- ↑ Thornburg, David D. (September 1980). "Computers and Society.". Compute (Small Systems Services Inc.): 13. http://archive.org/details/1980-09-compute-magazine.

- ↑ Libes, Sol (September 1980). "Random Bits". Byte (McGraw Hill): 168. http://archive.org/details/byte-magazine-1980-09.

- ↑ Byte Magazine Volume 06 Number 03 - Programming Methods. McGraw Hill. March 1981. p. 68. http://archive.org/details/byte-magazine-1981-03.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "State of Micrfocomputing" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.): pp. 11, 12. 14 September 1981. https://books.google.com/books?id=Mj0EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ Reimer, Jeremy (15 December 2005). "Total share: 30 years of personal computer market share figures" (in en-us). https://arstechnica.com/features/2005/12/total-share/.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "400% Rise in home-computer sales predicted for '82" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.). 20 September 1982. https://books.google.com/books?id=BDAEAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ "Atari News". A.N.A.L.O.G. Computing Magazine (Analog Magazine Corporation): 9. September 1981. http://archive.org/details/analog-computing-magazine-04.

- ↑ Carl Warren: "Atari Model 800 Personal Computer." Popular Electronics, June 1981, P. 49.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Hot Lines and Holograms" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.): pp. 29. 2 March 1981. https://books.google.com/books?id=jT4EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ Hogan, Thom (31 August 1981). "Today's Chaos" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.): pp. 7. https://books.google.com/books?id=rD0EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ "New VP Marketing At Atari's Computer Division". Compute! (Small Systems Services Inc.): 168. April 1981. http://archive.org/details/1981-04-compute-magazine.

- ↑ "Price Reductions, New Software Announced For Atari Computers.". Compute! (Small Systems Services Inc.): 158. June 1981. http://archive.org/details/1981-06-compute-magazine.

- ↑ "New Products – The Atari 400 Computer System.". The Atari Connection (Atari Connectgion): 2. September 1981. http://archive.org/details/Atari_Connection_Volume_1_Number_3_1981-09_Atari_US.

- ↑ Bills, Richard (May 1981). "Hardware Information". Compute! (Small Systems Services Inc.): 80. http://archive.org/details/1981-05-compute-magazine.

- ↑ "Atari Launches Major Software Acquisition Program". Compute! (Small Systems Services Inc.): 150. May 1981. http://archive.org/details/1981-05-compute-magazine.

- ↑ deWitt, Robert (June 1983). "APX – On top of the heap". Antic (Antic Publishing): 11. http://archive.org/details/1983-06-anticmagazine.

- ↑ "The new Atari Personal Computers". Ingersoll Atari Owners Club. July 1981. p. 5. http://archive.org/details/Ingersolls_Atari_Owners_Club_Bulletin_No._16_1981-07_Ingersoll_Electronics_GB.

- ↑ "Die Computer des Jahres." Chip;;, Dezember 1981, P. 16 f.

- ↑ "Banc d’essai: l’Atari 800." L’Ordinateur Individuel, September 1982, P. 155.

- ↑ "Conclusions." L’Ordinateur Individuel, September 1982, P. 160.

- ↑ Frank, Guido (16 April 2015). "Videospielgeschichten.de - Press meets Atari - Erinnerungen von Renate Knüfer". http://www.videospielgeschichten.de/pressmeetsatari.html.

- ↑ Atari Deutschland: "Atari Fachhändler." Chip, July 1982, P. 46.

- ↑ "Advertisement" Chip, September 1981, P. 101.

- ↑ "Atari" Chip Special 3, 1980, P. 9.

- ↑ Moore, Herb (October 1982). Upgrades Available. Antic Publishing. 15. http://archive.org/details/1982-10-anticmagazine.

- ↑ Hanson, Steve (October 1981). "Documented Atari Bugs". Compute! (Small Systems Services Inc.): 94. http://archive.org/details/1981-10-compute-magazine.

- ↑ Dvorak, John C. (14 June 1982). "Will the market ruin itself?" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.): p. 57. https://books.google.com/books?id=YDAEAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ Needle, David (20 September 1982). "400% rise in home-computer sales predicted for 82" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.): pp. 12. https://books.google.com/books?id=BDAEAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ "Lower prices herald new year" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group,Inc.): pp. 1. 25 January 1982. https://books.google.com/books?id=cz4EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ Wolfgang Taschner: "Billig wie noch nie." Chip, January 1983, P. 62.

- ↑ Nocera, Joseph (11 August 1984). "Death of a computer" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.): pp. 63. https://books.google.com/books?id=wy4EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ "Atari Announces Discount Fares To The Computer Age". Atari Connection (Atari, Inc.): 2. September 1982. http://archive.org/details/Atari_Connection_Volume_2_Number_3_1982-09_Atari_US\.

- ↑ DeWitt, Robert (November 1983). "Service System". Antic (Antic Publishing Inc.): 21. http://archive.org/details/1983-11-anticmagazine.

- ↑ "Coast to Coast Service for your Atari Home Computer". Atari Connection (Atari, Inc.): 14. June 1982. http://archive.org/details/Atari_Connection_Volume_2_Number_2_1982-06_Atari_US.

- ↑ "Home Computer Market Gets Competitive". Byte (McGraw Hill): 458. October 1982. https://archive.org/stream/BYTE_Vol_07-10_1982-10_Computers_in_Business/BYTE%20Vol%2007-10%201982-10%20Computers%20in%20Business#page/n459/mode/2up/. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ↑ Libes, Sol (August 1982). "Race for Space". Byte (McGraw Hill): 448. http://archive.org/details/byte-magazine-1982-08.

- ↑ Philip Faflick, Robert T. Grieves: "The Hottest-Selling Hardware." Time (magazine) , 3. January 1983, P. 37.

- ↑ Hubner, John (28 November 1983). "What went wrong at Atari?" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.): p. 157. https://books.google.com/books?id=sy8EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ Caparell, Jim (October 1982). "Editorial". Antic Magazine (Antic Publishing Inc.): 9. http://archive.org/details/1982-10-anticmagazine.

- ↑ "er verkaufte wie viele Computer?" P.M. Computerheft, 1/1983, P. 67.

- ↑ Frank, Guido (16 April 2015). "Videospielgeschichten.de - Klaus Ollmann - Erinnerungen des deutschen Atari Managers" (in de). http://www.videospielgeschichten.de/koerinnerungen.html.

- ↑ Spahr, Wolfgang (21 August 1982). "Atari Making Inroads in Germany" (in en). Billboard (Nielsen Business Media, Inc.): 61. https://books.google.com/books?id=1yQEAAAAMBAJ. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ↑ "Atari 1200XL". Byte (McGraw Hill): 486. April 1983. http://archive.org/details/byte-magazine-1983-04.

- ↑ "Prices continue dropping". Byte (McGraw Hill): 495. May 1983. http://archive.org/details/byte-magazine-1983-05.

- ↑ Lemmons, Phil (September 1983). "A bird's-eye view of the latest offerings". Byte (McGraw Hill): 230. http://archive.org/details/byte-magazine-1983-09.

- ↑ Mace, Scott (1 August 1983). "Morgan replaces Kassar as Atari CEO" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.): p. 3. https://books.google.com/books?id=vy8EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ Bisson, Giselle (6 August 1984). "Atari: From starting block to auction block" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.): p. 52. https://books.google.com/books?id=HC8EAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ Leitenberger, Bernd (2014). Computergeschichte(n) Die ersten Jahre des PC (1. Aufl ed.). Norderstedt: Books on Demand. p. 297. ISBN 978-3-7357-8210-6. OCLC 895312826. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/895312826. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ↑ "FPGA Atari 800XL". 24 December 2014. http://ssh.scrameta.net/.

- ↑ Mentley, David E. (1984). ABCs of Atari Computers. Datamost. ISBN 978-0-8359-0013-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=PkMSAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Herring, Richard (March 1983). "Anatomy of an Atari". Antic Magazine (Antic Publishing Inc): 17ff. http://archive.org/details/1983-04-anticmagazine.

- ↑ "The Atari 400/800 Computer Systems". http://www.atarimuseum.com/computers/8BITS/400800/ATARI800/A800.html.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 "Atari 400/800 Service Manual". http://www.jsobola.atari8.info/dereatari/literatdere/400_800sm.pdf.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 "Bits and Bytes". https://www.atariarchives.org/creativeatari/Bits_and_Bytes.php.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Lendino, Jamie (16 March 2017). Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation. Ziff Davis. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-0-692-85127-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=DkaoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA36. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ↑ "The Dark Secrets of ANTIC and CTIA". https://www.atariarchives.org/creativeatari/The_Dark_Secrets_of_ANTIC_and_CTIA.php.

- ↑ Julian Reschke, Andreas Wiethoff: Das Atari Profibuch. Sybex Verlag, 2. Volume 1986, P. 201–214

- ↑ Eichler, Grohmann: Atari Intern. Data Becker, 1. Volume 1984, P. 74.

- ↑ Eichler, Grohmann: Atari Intern. Data Becker, 1. Volume 1984, P. 41.

- ↑ The creative Atari. Small, David., Small, Sandy., Blank, George.. Morris Plains, (N.J.): Creative Computing Press. 1983. ISBN 0-916688-34-8. OCLC 9614769. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/9614769. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ↑ atari :: 400 800 :: CO16555 Atari Home Computer Technical Reference Notes 1982. ATARI Corp.. 1982. pp. VII.I. http://archive.org/details/bitsavers_atari40080mputerTechnicalReferenceNotes1982_20170986.

- ↑ "Atari Chips". http://www.atarihq.com/danb/AtariChips.shtml.

- ↑ "The Dark Secrets of ANTIC and CTIA". https://www.atariarchives.org/creativeatari/The_Dark_Secrets_of_ANTIC_and_CTIA.php.

- ↑ Julian Reschke, Andreas Wiethoff: Das Atari Profibuch.Sybex Editorial, 2. Vol 1986, P. 130.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 "Physical Types of Memory". https://www.atariarchives.org/creativeatari/Physical_Types_of_Memory.php.

- ↑ Atari, Inc.: Technical Reference Notes – Configurations. Sunnyvale, 1982, P. 28.

- ↑ "Interfacing Your Atari". https://www.atariarchives.org/creativeatari/Interfacing_Your_Atari.php.

- ↑ Lendino, Jamie (16 March 2017). Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation. Ziff Davis. pp. 39, 245. ISBN 978-0-692-85127-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=DkaoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA36. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ↑ "Compute!'s First Book of Atari". https://www.atariarchives.org/c1ba/page174.php.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 Lendino, Jamie (16 March 2017). Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation. Ziff Davis. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-692-85127-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=DkaoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA36. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ↑ Eirich, Dietmar. Computer-Peripherie alles über: Diskettenlaufwerk - Drucker - Monitore - Modems - Schnittstellen u. was sonst noch zu Ihrem Computer gehört (Orig.-Ausg ed.). München. pp. 51–53. ISBN 978-3-453-47058-3. OCLC 74773136. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/74773136. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ↑ User’s Handbook to the Atari Computer, P. 14

- ↑ Carl M. Evans: "Tale of Two Circuits." Antic Magazine, December 1982/January 1983, P. 63.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Lendino, Jamie (16 March 2017). Breakout: How Atari 8-Bit Computers Defined a Generation. Ziff Davis. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-692-85127-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=DkaoDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA36. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ↑ "Atari 810 Disk Drive". A.N.A.L.O.G. Computing Magazine (Analog Magazine Corporation). January 1981. http://archive.org/details/analog-computing-magazine-inserts-01.

- ↑ "Everything you always wanted to know about disk drives and DOS.". https://www.atarimagazines.com/creative/v11n8/100_Everything_you_always_wan.php.

- ↑ Marty Goldberg, Curt Vendel: Atari Inc. Business is Fun. Syzygy Company Press, 2012, P. 478.

- ↑ "Introducing the PERCOM Alternative to ATARI Disk Storage". Antic Magazine (Antic Publishing Inc.): 5. August 1982. http://archive.org/details/1982-08-anticmagazine.

- ↑ Lawrence, Winston (September 1982). "Hardware Review: Percom Double Density Disk Drive". A.N.A.L.O.G. (Analog Magazine Corporation): 57. http://archive.org/details/analog-computing-magazine-07.

- ↑ Systems, Introducing the RANA 1000 disk drive. (March 1983). "Introducing the RANA 1000 disk drive". Byte (McGraw Hill): 48. http://archive.org/details/byte-magazine-1983-03.

- ↑ Systems, Astra (July 1983). "Look what we have for your Atari Computer". Antic Magazine (Antic Publishing Inc.): 39. http://archive.org/details/1983-07-anticmagazine.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 Small, David and Sandy (December 1983). "Fast Drives". Antic Magazine (Antic Publishing, Inc.): 112f. http://archive.org/details/1983-12-anticmagazine.

- ↑ Disk System Installation Guide – Atari 800. Corvus Systems, 1982, P. 12.

- ↑ Inc, InfoWorld Media Group (28 June 1982). "Hardware News" (in en). InfoWorld : The Newspaper for the Microcomputing Community (InfoWorld Media Group, Inc.): pp. 87. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZTAEAAAAMBAJ.

- ↑ "Corvus Announces Mass Storage And Network Systems For Atari 800". Compute! (Small Systems Services Inc.): 191. July 1982. http://archive.org/details/1982-07-compute-magazine.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 Nautical Research Journal. Nautical Research Guild.. 1989. p. 38. https://books.google.com/books?id=nXcqAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ DeWitt, Robert (January 1984). "Printer Survey". Antic Magazine (Antic Publishing, Inc): 53. http://archive.org/details/1984-01-anticmagazine.

- ↑ Moriarty, Brian (November 1982). "Hardware Review: The Voicebox". A.N.A.L.O.G. Computing (Analog Magazine Corporation): 34. http://archive.org/details/analog-computing-magazine-08.

- ↑ Moriarty, Brian (September 1982). "Stereo Graphics Tutorial". A.N.A.L.O.G. Magazine (Analog Magazine Corp.): 70. http://archive.org/details/analog-computing-magazine-07.

- ↑ Myotis Systems (February 1983). "The Apprentice". Antic Magazine (Antic Publishing, Inc.): 38. http://archive.org/details/1983-02-anticmagazine.

- ↑ Starr, Michael; Chapple, Craig (9 July 2008). VINTROPEDIA - Vintage Computer and Retro Console Price Guide 2009. Lulu.com. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-1-4092-1277-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=D7RS9yegrtoC&pg=PA130. Retrieved 11 March 2021.