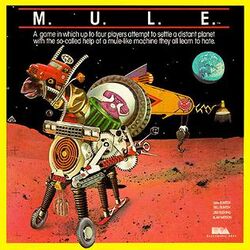

Software:M.U.L.E.

| M.U.L.E. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Ozark Softscape Bullet Proof Software (MSX) Eastridge Technology (NES) |

| Publisher(s) | |

| Designer(s) | Danielle Bunten Berry |

| Platform(s) | Atari 8-bit, Commodore 64, IBM PC, MSX2, NES, PC-88, Sharp X1 |

| Release | 1983: Atari 8-bit, C64 1985: IBM PC |

| Genre(s) | Business simulation game |

| Mode(s) | Single-player 2-4 player multiplayer |

M.U.L.E. is a 1983 multiplayer video game written for the Atari 8-bit family of home computers by Ozark Softscape. Designer Danielle Bunten Berry (credited as Dan Bunten) took advantage of the four joystick ports of the Atari 400 and 800 to allow four-player simultaneous play. M.U.L.E. was one of the first five games published in 1983 by new company Electronic Arts, alongside Axis Assassin, Archon, Worms?, and Hard Hat Mack.[2][3] Primarily a turn-based strategy game, it incorporates real-time elements where players compete directly as well as aspects that simulate economics.

The game was ported to the Commodore 64, Nintendo Entertainment System, and IBM PC (as a self-booting disk).[4] Japanese versions also exist for the PC-88,[5] Sharp X1,[6] and MSX2 computers.[7] Like the subsequent models of the Atari 8-bit family, none of these systems allow four players with separate joysticks. The Commodore 64 version lets four players share joysticks, with two players using the keyboard during action portions.[8]

Gameplay

Set on the fictional planet Irata (Atari backwards), the game is an exercise in supply and demand economics involving competition among four players, with computer opponents automatically filling in for any missing players. Players choose the race of their colonist, which has advantages and disadvantages that can be paired to their respective strategies. To win, players not only compete against each other to amass the largest amount of wealth, but must also cooperate for the survival of the colony.

Central to the game is the acquisition and use of Multiple Use Labor Elements, or M.U.L.E.s, to develop and harvest resources from the player's real estate. Depending on how it is outfitted, a M.U.L.E. can be configured to harvest Energy, Food, Smithore (from which M.U.L.E.s are constructed), and Crystite (a valuable mineral available only at the "Tournament" level). Players must balance supply and demand of these elements, buying what they need and selling what they don't. Players may exploit or create shortages by refusing to sell to other players or to the "store", which raises the price of the resource on the following turns. Scheming between players is encouraged by allowing collusion, which initiates a mode allowing a private transaction. Crystite is the one commodity that is not influenced by supply and demand considerations, being deemed to be sold off-world, so the strategy with this resource is somewhat different; a player may attempt to maximize production without fear of having too much supply for the demand.

Each resource is required to do certain things on each turn. For instance, if a player is short on Food, there is less time to take one's turn. If a player is short on Energy, some land plots won't produce any output, while a shortage of Smithore raises the price of M.U.L.E.s and prevents the store from manufacturing new M.U.L.E.s.

Players must deal with periodic random events such as runaway M.U.L.E.s, sunspot activity, theft by space pirates, and meteorites,[9] with potentially destructive and beneficial effects. Favorable random events almost never happen to the player currently in first place, while unfavorable events never happen to the player in last place.[10] Similarly, when two players want to buy a resource at the same price, the player in the losing position automatically wins. Players also can hunt the mountain wampus for a cash reward.

Development

According to Jim Rushing (one of the four original partners in Ozark Softscape), M.U.L.E. was initially called Planet Pioneers during development.[11] It was intended to be similar to Cartels & Cutthroats, with more graphics, better playability, and a focus on multiplayer.[12] The real-time auction element came largely from lead designer Danielle Bunten's Wheeler Dealers. The board game Monopoly was used as a model for the game because of its encouragement of social interaction and for several of the game's elements: the acquisition and development of land as a primary task, a production advantage for grouped plots, different species (à la the different player tokens), and random events similar to "Chance" cards.[12] Additional game features such as claim jumping, loans, and crystite depletion were discarded for adding complexity without enhancing gameplay.

The setting was inspired by Robert A. Heinlein's Time Enough for Love, wherein galactic colonization is in the style of the American Old West: A few pioneers with drive and primitive tools. The M.U.L.E. itself is based on the idea of the genetically modified animal in Heinlein's novel and given the appearance of a Star Wars Imperial Walker. Another Heinlein novel, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, provided the decision to not have any government or external authority. In the game's original designs, land was sold by auction, but this caused a feedback loop in which the wealthiest player had the most land and thus made the most money; thus, the developers created the "land authority" that gives each player a free plot of land each turn.[12]

Ozark Softscape developed the game for the Atari 8-bit family first because of its policy of developing for the most advanced computers then porting them to other platforms, removing or altering features such as sprites as necessary. Bunten stated that Ozark did not port the game to the Apple II because "M.U.L.E. can't be done for an Apple".[13] The IBM PC port of M.U.L.E was developed by K-Byte Software, an affiliate of Electronic Arts, and published by IBM.

Reception

| Reception | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

M.U.L.E. only sold 30,000 copies[15] but was lauded by reviewers.

Computer Gaming World described it as a "fascinating and very enjoyable game which comes to its very best point with four human players". Minor criticisms included too-weak computer opponents and the lack of a save feature.[16] Praising the "human engineering" that created the Atari 8-bit version's user interface, the magazine called it "All in all, a superior game".[17] Softline called M.U.L.E. "what computer games should be like. It's a game, and it's a learning experience. It's also stimulating, fun, frustrating, thought provoking, fun, addictive, and fun". The magazine praised it as offering "valuable lessons" on economic topics, noting that "Most of them are learned the hard way", and concluded that "The game feels good" and "virtually flawless" because of the human-computer and human-human competition.[18]

John J. Anderson wrote in Creative Computing, "I should also mention that there is no shooting to be found anywhere in the game. How positively refreshing ... Mule belongs on every Atari software shelf in the world: in every home and every school, near every Atari."[19]

Scott Mace of InfoWorld called M.U.L.E. unusual in the ease with which it allows multiplayer interaction through a single game computer console. He wrote that it would have "incredible lasting power, just like the best of the board games" and stated "I learned more about the economics of the marketplace from M.U.L.E. than I ever did in college".[20] Leo Laporte of Hi-Res also said that he learned more economics from the game than during college. He predicted that M.U.L.E. "may revitalize the [video game] industry. It ought to make them rich anyway", praised its theme as "most captivating musical come-on I've ever heard", and concluded "If you ask me, M.U.L.E. is the perfect game."[21]

Reporting in BYTE that his children loved it, Jerry Pournelle described M.U.L.E. as "a cross between Hammurabi, Diplomacy, and an arcade game, with lots of strategic decisions—provided that you're skillful enough with a joystick to implement what you've decided to do".[22] Another reviewer wrote in the magazine that "it is impossible to adequately describe all the interaction and economically realistic subtleties of M.U.L.E.", concluding that it was "an intriguing way to illustrate some of the triumphs and perils of free enterprise".[23] Orson Scott Card in Compute! in 1983 gave M.U.L.E. and two other EA games, Archon and Worms?, complimentary reviews, writing that "they are original; they do what they set out to do very, very well; they allow the player to take part in the creativity; they do things that only computers can do".[24] The magazine listed the game in May 1988 as one of "Our Favorite Games", stating that it "requires a sense of strategy as well as proficiency at joystick maneuvers".[25]

Steven A. List reviewed M.U.L.E. in Space Gamer No. 70. He commented that "M.U.L.E. is simply a great game, a tour de force in programming and design, good family entertainment, educational and exciting. If you don't have a computer and disk drive, it may be worth the investment just to be able to play this."[26] The Addison-Wesley Book of Atari Software 1984 gave the game an overall A rating, stating that it "combines some of the best features of Monopoly with economic simulation games like [Hammurabi]" while teaching "valuable lessons in economies in a fun way". The book noted that "when several people play, the game becomes involved and interactive".[27] Two of Zzap!64's reviewers stated in 1985 that M.U.L.E. was "an excellent trading game" and "recommended for both novice and skilled", while the third complained that he "found little [excitement] ... nothing to keep me interested".[28]

In 1984 M.U.L.E. was awarded "1984 Best Multi-Player Video Game/Computer Game" at the 5th annual Arkie Awards where judges described it as "a unique blend of boardgame strategy and computer-game pacing" and noted that "since its release, 'M.U.L.E.' has gained an intense cult following".[29]: 29 Softline readers named the game the third most-popular Atari program of 1983.[30] With a score of 7.44 out of 10, in 1988 M.U.L.E. was among the first members of the Computer Gaming World Hall of Fame, honoring those games rated highly over time by readers.[31] In 1992 and 1994 surveys of science fiction games the magazine gave the title five of five stars, calling it "An all-time computer classic, this was one of the only games ever devised that was playable and entertaining for four humans. Economics made fun! ... it still holds up well over all these years and, by itself, provides justification for holding onto the 8-bit Atari".[14][32] In 1996, the magazine named M.U.L.E. as #3 on its Best Games of All Time list.[33] In 2004, M.U.L.E. was inducted into GameSpot's list of the greatest games of all time.[34] It was named #5 of the "Ten Greatest PC Games Ever" by PC World in 2009.[35] M.U.L.E. was listed as the 19th most important video game of all time by 1UP.com.[36] Chris Crawford said of the game that considering the platform the team had to deal with, M.U.L.E. was "the greatest game design ever done."[37]

Legacy

Shigeru Miyamoto cited M.U.L.E. as an influence on the Pikmin series.[38] Will Wright dedicated his game The Sims to the memory of Bunten. The M.U.L.E. theme song was included in Wright's later game, Spore, as an Easter egg in the space stage.

A 2007 remix of the theme song by 8 Bit Weapon is used in the video game Roblox.

An ability in StarCraft II allows Terran players to deploy temporary robotic workers called M.U.L.E.s.

A board game adaptation, M.U.L.E. The Board Game, was released in 2015.[39]

Unofficial clones are Subtrade, Traders, and Space HoRSE.

Enhanced versions

In 2005, a netplay component was integrated into the Atari800WinPlus emulator enabling the original game to be played over the Internet.[40]

Computer Gaming World printed in April 1994 that EA "was working on a videogame version of the game, but the design was terminated because of creative differences between the publisher and the designer".[41] The magazine reported a rumor in May 1994 that a "Genesis version has been completed, but EA is debating over its release",[32] and then in August 1994 that Bunten had decided against remaking the game because EA "wanted me to put in guns and bombs". An editorial asked the company to "give us M.U.L.E. with Smithore and Crystite as its creator intended".[42] Bunten was working on an Internet version of M.U.L.E. until her death in 1998.

An online, licensed remake called Planet M.U.L.E. was released in 2009. The game is free for download for major platforms.[43] Comma 8 Studios later acquired the mobile M.U.L.E. license and released M.U.L.E. Returns for iOS in November 2013.[44]

The source code to M.U.L.E., believed lost, was revealed in 2020 to be in the possession of Julian Eggebrecht. In the 1980s he had pitched an enhanced 16-bit version of the game. EA accepted the idea and sent him two discs with the source code of the original.[45]

Another officially licensed version called M.U.L.E. Online was released via the itch.io platform on May 30, 2023. This version faithfully recreates the Atari 8-bit version of the game with both local and online multiplayer included and enhanced keyboard, mouse, and gamepad controls. It is available for Windows, macOS and Linux.[46]

World records

According to Twin Galaxies, the following records are recognized:

- Nintendo Entertainment System - Jason P. Kelly - 68,273

- Commodore 64 - John J. Sato - 57,879[47]

See also

- Legged Squad Support System, real-life robotic pack animal developed in 2009

References

- ↑ "GameFAQs - Game Companies: Bullet Proof Software". CBS Interactive Inc.. http://www.gamefaqs.com/features/company/72801.html.

- ↑ Corriea, Alexa Ray (May 21, 2013). "30 years ago Electronic Arts shipped its first batch of five games". https://www.polygon.com/2013/5/21/4351144/30-years-ago-electronic-arts-shipped-its-first-batch-of-five-games.

- ↑ "28 Years of EA History". May 20, 2011. https://www.ea.com/news/today-in-ea-history.

- ↑ Danielle Berry at MobyGames

- ↑ "Entry with PC-88 info and shots at Mobygames". http://www.mobygames.com/game/pc88/mule.

- ↑ "Entry at thelegacy.de with screenshots of the X1 port". http://www.thelegacy.de/Museum/6820/.

- ↑ "Entry at Generation-MSX". http://www.generation-msx.nl/msxdb/softwareinfo/1224.

- ↑ "M.U.L.E. Command Summary Card for the Commodore 64 (pages 1 and 2)". http://www.c64sets.com/details.html?id=1732.

- ↑ "PC Retroview: M.U.L.E. - PC Feature at IGN". Pc.ign.com. 2000-07-05. http://pc.ign.com/articles/081/081722p1.html.

- ↑ "Designing People...". Computer Gaming World: 48–54. August 1992. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1992&pub=2&id=97. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- ↑ Szczepaniak, John. "Mechanical Donkeys". The Gamer's Quarter, Issue #6. World of M.U.L.E.. http://www.worldofmule.net/tiki-index.php?page=MechanicalDonkeysJimRushing. "Rushing: We can discuss more on phone, but ... Trivia: Working title of the game was "Planet Pioneers.""

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Bunten, Dan (April 1984). "Dispatches / Insights from the Strategy Game Design Front". Computer Gaming World: pp. 17, 42.

- ↑ Bunten, Dan (December 1984). "Dispatches / Insights From the Strategy Game Design Front". Computer Gaming World: 40.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Brooks, M. Evan (November 1992). "Strategy & Wargames: The Future (2000-....)". Computer Gaming World: 99. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1992&pub=2&id=100. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ↑ "Notes on the Conference on Computer Game Design". Computer Gaming World: pp. 16–17, 28–29, 54–55. February 1989.

- ↑ Curtis, Edward (Jul–Aug 1983). "M.U.L.E.". Computer Gaming World: 12–13. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1983&pub=2&id=11.

- ↑ Doum, Allen (October 1983). "Atari Arena". Computer Gaming World 1 (12): 43.

- ↑ Yuen, Matt (Sep–Oct 1983). "M.U.L.E.". Softline: pp. 42. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1983&pub=6&id=13.

- ↑ Anderson, John J. (December 1983). "M.U.L.E". Creative Computing. pp. 114. http://www.atarimagazines.com/creative/v9n12/114_MULE.php.

- ↑ Mace, Scott (1983-12-05). "Electronic Antics". InfoWorld: 111–112. https://books.google.com/books?id=6C8EAAAAMBAJ&q=%22m.u.l.e.%22+%22electronic+arts%22&pg=PA111. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ↑ LaPorte, Leo G. (May–June 1984). "M.U.L.E.". Hi-Res: pp. 14. http://www.atarimagazines.com/hi-res/v1n4/reviews.php.

- ↑ Pournelle, Jerry (November 1984). "NCC Reflections". BYTE: pp. 361. https://archive.org/stream/byte-magazine-1984-11/1984_11_BYTE_09-12_New_Chips#page/n359/mode/2up.

- ↑ Smarte, Gene (March 1984). "M.U.L.E". BYTE: pp. 296. https://archive.org/stream/byte-magazine-1984-03-rescan/1984_03_BYTE_09-03_Simulation#page/n297/mode/2up.

- ↑ Card, Orson Scott (November 1983). "Home Computer Games Grow Up". Compute!: pp. 162. http://www.atarimagazines.com/compute/issue42/gamesgrowup.php.

- ↑ "Our Favorite Games". Compute!: pp. 12. May 1988. https://archive.org/stream/1988-05-compute-magazine/Compute_Issue_096_1988_May#page/n13/mode/2up.

- ↑ List, Steven A. (July–August 1984). "Capsule Reviews". Space Gamer (Steve Jackson Games) (70): 48, 50.

- ↑ The Addison-Wesley Book of Atari Software. Addison-Wesley. 1984. pp. 193. ISBN 0-201-16454-X. https://archive.org/stream/Atari_Software_1984#page/n193/mode/2up.

- ↑ Wade, Bob; Penn, Gary; Rignall, Julian (June 1985). "M.U.L.E". Zzap!64: pp. 24–25. https://archive.org/stream/zzap64-magazine-002/ZZap_64_Issue_002_1985_Jun#page/n23/mode/2up.

- ↑ Kunkel, Bill; Katz, Arnie (February 1984). "Arcade Alley: The 1984 Arcade Awards, Part II". Video (Reese Communications) 7 (11): 28–29. ISSN 0147-8907.

- ↑ "The Best and the Rest". St.Game: pp. 49. Mar–Apr 1984. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1984&pub=6&id=16.

- ↑ "The CGW Hall of Fame". Computer Gaming World: 44. March 1988. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1988&pub=2&id=45.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Brooks, M. Evan (May 1994). "Never Trust A Gazfluvian Flingschnogger!". Computer Gaming World: 42–58. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1994&pub=2&id=118.

- ↑ "150 Best Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World: 64–80. November 1996. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1996&pub=2&id=148. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ↑ "The Greatest Games of All Time: M.U.L.E.". http://www.gamespot.com/gamespot/features/all/greatestgames/p-54.html.

- ↑ Edwards, Benj (February 8, 2009). "The Ten Greatest PC Games Ever". PC World. http://www.pcworld.com/article/158850/best_pc_games.html#slide7. Retrieved 2016-05-01.

- ↑ Parish, Jeremy; Sharkey, Scott. "19. M.U.L.E.". http://www.1up.com/features/essential-50-mule.

- ↑ Rouse III, Richard (2005). Game Design Theory & Practice. Wordware Publishing, Inc.. p. 269. ISBN 1-55622-912-7.

- ↑ "任天堂の宮本 茂氏に聞く,「ピクミン3」の魅力――「インタラクティブメディアは,"自分"が関わっていることが一番面白い」". http://www.4gamer.net/games/168/G016837/20130712087/index_2.html.

- ↑ "M.U.L.E. The Board Game". https://boardgamegeek.com/boardgame/182619/mule-board-game.

- ↑ Glicker, Stephen (11 November 2005). "Atari MULE Online". http://www.gamingsteve.com/archives/2005/11/atari_mule_onli_1.php.

- ↑ Gerhart, Emory (April 1994). "Ass-inine Answer". Computer Gaming World: 146. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1994&pub=2&id=117.

- ↑ Sipe, Russell (August 1994). "You Can't Change That!". Computer Gaming World: 8. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1994&pub=2&id=121.

- ↑ "Planet M.U.L.E. official site". Planetmule.com. http://www.planetmule.com.

- ↑ "Presentation "M.U.L.E. Returns" at World of Commodore 2012". December 1, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8KiNs4EagPI.

- ↑ M.U.L.E. – Nachtrag at stayforever.de

- ↑ "M.U.L.E. Online". June 5, 2023. https://puzzud.itch.io/mule-online.

- ↑ "Twin Galaxies". http://www.twingalaxies.com/scores.php.

External links

- M.U.L.E. at Atari Mania

- The Atari 8-bit version of M.U.L.E. can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive

- Article from The Arkansas Times about Bunten and M.U.L.E.

- Review of M.U.L.E. board game

- M.U.L.E. Online

|