Engineering:Blackburn Buccaneer

| Buccaneer | |

|---|---|

| |

| A Buccaneer taking off from Faro, Portugal | |

| Role | Maritime strike aircraft |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer |

|

| First flight | Script error: No such module "Date time". |

| Introduction | Script error: No such module "Date time". |

| Retired | 31 March 1994 |

| Primary users | Royal Navy |

| Number built | 211 (including 2 prototypes)[1] |

The Blackburn Buccaneer is a British carrier-capable attack aircraft designed in the 1950s for the Royal Navy (RN). Designed and initially produced by Blackburn Aircraft at Brough, it was later officially known as the Hawker Siddeley Buccaneer when Blackburn became a part of the Hawker Siddeley Group, but this name is rarely used.

The Buccaneer was originally designed in response to the Soviet Union introducing the Sverdlov class of light cruisers. Instead of building a new class of its own cruisers, the Royal Navy decided that it could address the threat posed via low-level attack runs performed by Buccaneers, so low as to exploit the ship's radar horizon to minimise the opportunity for being fired upon. The Buccaneer could attack using nuclear weapons or conventional munitions. During its service life, it would be modified to carry anti-ship missiles, allowing it to attack vessels from a stand-off distance and thus improve its survivability against modern ship-based anti-aircraft weapons.[2] The Buccaneer performed its maiden flight in April 1958 and entered Royal Navy service during July 1962.

Initial production aircraft suffered a series of accidents, largely due to insufficient engine power; this shortfall would be quickly addressed via the introduction of the Buccaneer S.2, equipped with more powerful Rolls-Royce Spey jet engines, in 1965. The Buccaneer S.2 would be the first Fleet Air Arm (FAA) aircraft to make a non-stop, unrefuelled crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. During the 1960s and 1970s, the Royal Navy standardised the air wings operating from their carriers around the Buccaneer, Phantom, and the Fairey Gannet. The Buccaneer was also offered as a possible solution for the Royal Air Force (RAF) requirement for a supersonic interdictor carrying nuclear weapons. It was rejected as not meeting the specification in favour of the more advanced BAC TSR-2 bomber, but this aircraft would be cancelled largely due to its high cost, then its selected replacement, the General Dynamics F-111K, would also be cancelled. The Buccaneer was purchased as a TSR-2 substitute and entered RAF service during October 1969.

The Royal Navy retired the last of its large aircraft carriers in February 1979; as a result, the Buccaneer's strike role was transferred to the British Aerospace Sea Harrier and the Buccaneers were transferred to the RAF. After a crash in 1980 revealed metal fatigue problems, the RAF's fleet was reduced to 60 aircraft while the rest were withdrawn. The ending of the Cold War in the 1990s led to military cutbacks that accelerated the retirement of Britain's remaining Buccaneers; the last of the RAF's Buccaneers were retired in March 1994 in favour of the more modern Panavia Tornado. The South African Air Force (SAAF) was the only export customer for the type. Buccaneers saw combat action in the first Gulf War of 1991, and the lengthy South African Border War.

Development

Royal Navy

Following the end of the Second World War, the Royal Navy soon needed to respond to the threat posed by the rapid expansion of the Soviet Navy. Chief amongst Soviet naval developments in the early 1950s was the Script error: The function "sclass" does not exist.; these vessels were classifiable as light cruisers, being fast, effectively armed, and numerous. Like the German "pocket battleships" during the Second World War, these new Soviet cruisers presented a serious threat to the merchant fleets in the Atlantic.[3] To counter this threat, the Royal Navy decided not to use a new ship class of its own, but instead introduce a specialised strike aircraft employing conventional or nuclear weapons. Operating from the Navy's fleet carriers, and attacking at high speed and low level, it would offer a solution to the Sverdlov problem.[4]

A detailed specification was issued in June 1952 as Naval Staff Requirement NA.39, calling for a two-seat aircraft with folding wings, capable of flying at 550 knots (1,020 km/h; 630 mph) at sea level, with a combat radius of 400 nautical miles (740 km; 460 mi) at low altitude, and 800 nautical miles (1,500 km; 920 mi) at higher cruising altitudes. A weapons load of 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) was required, including conventional bombs, the Red Beard free-fall nuclear bomb, or the Green Cheese anti-ship missile.[5] Based on the requirement, the Ministry of Supply issued specification M.148T in August 1952, and the first responses were returned in February 1953. Blackburn's design by Barry P. Laight, Project B-103, won the tender in July 1955.[6] For reasons of secrecy, the aircraft was called BNA (Blackburn Naval Aircraft) or BANA (Blackburn Advanced Naval Aircraft) in documents, leading to the nickname of "Banana Jet". The first prototype made its maiden flight from RAE Bedford on 30 April 1958.[7][8]

The first production Buccaneer model, the Buccaneer S.1, entered squadron service with the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) in January 1963.[9] It was powered by a pair of de Havilland Gyron Junior turbojets, producing 7,100 pounds-force (32,000 N) of thrust.[10] This mark was somewhat underpowered, and as a consequence, could not achieve take off if fully laden with both fuel and armament. A temporary solution to this problem was the "buddy system": aircraft took off with a full load of weaponry and minimal fuel, and would subsequently rendezvous with a Supermarine Scimitar that would deliver the full load of fuel by aerial refuelling.[11][12] The lack of power meant, however, that the loss of an engine during take-off, or landing at full load, when the aircraft was dependent on flap blowing, could be catastrophic.[13]

The long-term solution to the underpowered S.1 was the development of the Buccaneer S.2, fitted with the Rolls-Royce Spey engine, which provided 40% more thrust. The turbofan Spey also had significantly lower fuel consumption than the pure-jet Gyron, which provided improved range. The engine nacelles had to be enlarged to accommodate the Spey, and the wing required minor aerodynamic modifications as a result.[14] Hawker Siddeley announced the production order for the S.2 in January 1962.[15] All Royal Navy squadrons had converted to the improved S.2 by the end of 1966.[16] However, 736 Naval Air Squadron also used eight S.1 aircraft taken from storage to meet an extra training demand for RAF crews until December 1970.[17]

South African Air Force

In October 1962, 16 aircraft were ordered by the South African Air Force (SAAF), as the Buccaneer S.50.[18] These were S.2 aircraft with the addition of Bristol Siddeley BS.605 rocket engines to provide additional thrust for the "hot and high" African airfields. The S.50 was also equipped with strengthened undercarriage, and higher capacity wheel brakes, and had manually folded wings. They were equipped to use the AS-30 command guided air-to-surface missiles. Due to the need to patrol the vast coastline, they also specified aerial refueling, and larger 430-US-gallon (1,600 l; 360 imp gal) underwing tanks.[19] Once in service, the extra thrust of the BS.605 rocket engines proved to be unnecessary, and they were eventually removed from all aircraft.[20] South Africa later sought to procure further Buccaneers, but the British government blocked further orders, because of a voluntary arms embargo on that country.[21]

Royal Air Force

Blackburn's first attempt to sell the Buccaneer to the Royal Air Force (RAF) occurred in 1957–1958, in response to the Air Ministry Operational Requirement OR.339, for a replacement for the RAF's English Electric Canberra light bombers, with supersonic speed, and a 1,000-nautical-mile (1,900 km; 1,200 mi) combat radius; asking for an all-weather aircraft that could deliver nuclear weapons over a long range, operate at high level at Mach 2+ or low level at Mach 1.2, with STOL performance.[22] Blackburn proposed two designs, the B.103A, a simple modification of the Buccaneer S.1 with more fuel, and the B.108, a more extensively modified aircraft with more sophisticated avionics. Against a background of inter-service distrust, political issues, and the 1957 Defence White Paper, both types were rejected by the RAF; as being firmly subsonic, and incapable of meeting the RAF's range requirements; while the B.108, which retained Gyron Junior engines while being 10,000 pounds (4,500 kg) heavier than the S.1, would have been severely underpowered, giving poor short-take off performance. The BAC TSR-2 was eventually selected in 1959.[23][24]

After the cancellation of the TSR-2, and then the substitute American General Dynamics F-111K, the Royal Air Force still required a replacement for its Canberras in the low-level strike role, while the planned retirement for the Royal Navy's aircraft carriers meant that the RAF would also need to add a maritime strike capability. It was therefore decided in 1968 that the RAF would adopt the Buccaneer, both by the purchase of new-build aircraft, and by taking over the Fleet Air Arm's Buccaneers as the carriers were retired.[25][26][27] A total of 46 new-build aircraft for the RAF were built by Blackburn's successor, Hawker Siddeley, designated S.2B. These had RAF-type communications and avionics equipment, Martel air-to-surface missile capability, and could be equipped with a bulged bomb-bay door containing an extra fuel tank.[28]

Some Fleet Air Arm Buccaneers were modified in-service to also carry the Martel anti-ship missile. Martel-capable FAA aircraft were later redesignated S.2D. The remaining aircraft became S.2C. RAF aircraft were given various upgrades. Self-defence was improved by the addition of the AN/ALQ-101 electronic countermeasures (ECM) pod (also found on RAF's SEPECAT Jaguar GR.3), chaff and flare dispensers, and AIM-9 Sidewinder capability. RAF low-level strike Buccaneers could carry out what was known as 'retard defence'; four 1,000-pound (450 kg) retarded bombs carried internally could be dropped to provide an effective deterrent against any following aircraft. In 1979, the RAF obtained the American AN/AVQ-23E Pave Spike laser designator pod for Paveway II laser-guided bombs; allowing the aircraft to act as target designators for further Buccaneers, Jaguars, and other strike aircraft.[28] From 1986, No. 208 Squadron RAF, then No. 12 (B) Squadron, replaced the Martel ASM with the Sea Eagle missile.[29]

Proposed developments

Further developments beyond the Buccaneer S.2 were put forward by Hawker Siddeley in the 1960s and 1970s; however none would be pursued through to production by either the Royal Navy or the Royal Air Force. One such effort was designated as Buccaneer 2*, which was presented as a cost-effective alternative to the TSR-2. The 2* would have featured newer equipment; such as head-up displays and onboard computers from the cancelled Hawker Siddeley P.1154 VTOL aircraft, it would have also adopted the same radar system as that being developed for the TSR-2. An even more extensively upgraded model, the Buccaneer 2** was also mooted, which would have been furnished with more sophisticated land-strike capabilities derived from the TSR-2 again. According to Denis Healey, defence minister 1964–1970, the RAF had been hostile to the Buccaneer due to it being a naval aircraft; it has been further suggested that developing improved Buccaneers for the RAF would weaken arguments against the Royal Navy's planned CVA-01-class aircraft carriers.[30] In one report by the Ministry of Defence (MoD), it was claimed that two Buccaneer 2* could do the job of one General Dynamics F-111, for less than half the unit cost.[31]

Design

Overview

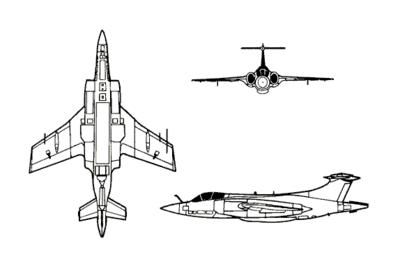

The Buccaneer was a mid-wing, twin-engine aircraft. It had a crew of two in a tandem-seat arrangement with the observer seated higher and offset from the pilot to give a clear view forwards to enable him to assist in visual search. Its operational profile included cruising at altitude (for reduced fuel consumption) before descending, just outside the anticipated enemy radar detection range, to 100 feet (30 m) for a 500-knot (930 km/h; 580 mph)[32] dash to and from the target. Targets might be ships-at-sea or large shore-based installations at long range from the launching aircraft-carrier.[33] To illustrate, in May 1966, an S.2 launched from Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist. in the Irish Sea, performed a low-level simulated nuclear weapon toss on the airfield at Gibraltar and returned to the ship, a 2,300-mile (3,700 km) trip[32] The aircraft had an all-weather operational capability provided by the pilot's head-up display and Airstream Direction Detector, for example, and the observer's navigation systems and fire control radar.[34] The Buccaneer was one of the largest aircraft to operate from British aircraft carriers, and continued operating from them until the last conventional carrier was withdrawn in February 1979.[35] During its service, the Buccaneer was the backbone of the Navy's ground strike operations, including nuclear strike.[35]

The majority of the rear fuselage's internal area was used to house electronics, such as elements of the radio, equipment supporting the aircraft's radar functionality, and the crew's liquid oxygen life support system; the whole compartment was actively cooled by ram air drawn from the tailfin.[36] For redundancy, the Buccaneer featured dual busbars for electrical systems, and three independent hydraulic systems.[37] The aircraft was made easier to control and land via an integrated flight control computer that performed auto-stabilisation and auto pilot functions.[38]

Armament and equipment

The Buccaneer had been designed specifically as a maritime nuclear strike aircraft. Its intended weapon was a nuclear air-to-surface missile codenamed Green Cheese but this weapon's development was cancelled, and in its place was the unguided 2,000-pound (900 kg) Red Beard, which had been developed for the English Electric Canberra. Red Beard had an explosive yield in the 10 to 20 kiloton range; and was mounted on a special bomb bay door, into which it nested neatly to reduce aerodynamic buffet on the launch aircraft. At low levels and high speeds, traditional bomb bay doors could not be opened safely into the air stream; therefore, Blackburn developed a revolving bomb bay which turned about the long axis of the aircraft, exposing the weapon load mounted on what was effectively the inside of the single bomb bay door and allowing it to be released quickly without creating a massive increase in drag; this feature also proved convenient in providing ground-level access and unintentionally improved the aircraft's stealth capability by not generating a large increase in the radar cross section.[39][40]

The bomb bay could also accommodate a 2,000-litre (440 imp gal; 530 US gal) ferry tank, a photo-reconnaissance 'crate', or a cargo container. The reconnaissance package featured an assortment of six cameras, each at different angles or having different imaging properties, and was only mounted on missions specifically involving reconnaissance activities.[41] The Buccaneer also featured four underwing hard points capable of mounting 1,000-pound (450 kg) bombs, missiles, fuel tanks, or other equipment such as flares;[35] later developments saw the adoption of wing-mounted electronic warfare and laser designator pods.[16] A similar underwing configuration was latterly adopted by the SAAF.[42] Upon its entry into service, the Buccaneer was capable of carrying practically all munitions then in use by Royal Navy aircraft.[43] It was intended for a pack with twin 30 mm (1.2 in) ADEN cannons to be developed for the Buccaneer, but the effort was abandoned and the type was never equipped with a gun.[44]

Early on in the Buccaneer's career, conventional anti-ship missions would have employed a mix of unguided bombs and rockets at close range. This tactic became increasingly impractical in the face of Soviet anti-aircraft missile advances; thus, later Buccaneers were adapted to make use of several missiles capable of striking enemy ships from a distance. The Anglo-French Martel missile was introduced upon the Buccaneer, but the weapon was said to have been "very temperamental", and its deployment required an attacking Buccaneer to increase its altitude and thus its vulnerability to being attacked itself.[28] An extensive upgrade programme undertaken in the 1980s added compatibility with several new pieces of equipment; including the Sea Eagle missile, a self-guiding 'fire-and-forget' missile capable of striking targets at an effective range of 60 miles (100 km), five times that of the Martel AJ 168 anti-ship missile, while also being significantly more powerful.[45]

Boundary layer control

In order to dramatically improve aerodynamic performance at slow speeds, such as during takeoff and landing, Blackburn adopted a new aerodynamic control technology, known as boundary layer control (BLC). BLC bled high-pressure air directly from the engines, which was "blown" against various parts of the aircraft's wing surfaces and horizontal stabiliser. A full-span slit along the part of the wing's trailing edge was found to give almost 50% more lift than any contemporary scheme.[46] In order to counteract the severe pitch movements that would otherwise be generated by use of BLC, a self-trimming system was interconnected with the BLC system, and additional blowing of the wing's leading edge was also introduced. The use of BLC allowed the use of slats to be entirely discarded in the design.[46]

Before landing, the pilot would open the BLC vents as well as lower the flaps to achieve slow, stable flight. A consequence of the blown wing was that the engines were required to run at high power for low-speed flight in order to generate sufficient compressor gas for blowing. Blackburn's solution to this situation was the adoption of a large air brake; this addition also allowed an overshooting aircraft to pull away more quickly during a failed landing attempt.[47] The nose cone and radar antenna could also be swung around by 180 degrees to reduce the length of the aircraft in the carrier hangar. This feature was particularly important due to the small size of the aircraft carriers from which the Buccaneer typically operated.[48]

For a carrier take-off, the Buccaneer was pulled tail-down on the catapult, with its nosewheel in the air to put the wing at about 11°. It could be launched "hands-off": the pilot able to leave the tailplane in a neutral position.[49] With blowing on, the Spey 101 output drops to around 9,100 pounds-force (40,000 N), though about 600 pounds-force (2,700 N) is recovered from the trailing edge slits which face aft. About 70% of the blown air goes over the flaps and ailerons, which are in a drooped position.[50] Off an aircraft carrier, the minimum launch speed was around 120 knots (220 km/h; 140 mph) at 43,000 pounds (20,000 kg); from an airfield, the Buccaneer took off in 3,000 feet (900 m) at 144 knots (267 km/h; 166 mph) with blown air. The figures become 3,700 feet (1,100 m) at 175 knots (325 km/h; 200 mph) without blown air.[51]

Fuselage and structure

The fuselage of the Buccaneer was designed using the area rule technique, which had the effect of reducing aerodynamic drag while travelling at transonic speeds,[52] and gave rise to the characteristic curvy "Coke bottle" shape of the fuselage. The majority of the airframe and fuselage was machined from solid castings to give the required strength to endure the stress of low-level operations. Considerable effort went into ensuring that metal fatigue would not be a limiting factor of the Buccaneer's operational life, even under the formidable conditions imposed of low level flight.[52] However, design changes for the Mark 2 Buccaneer, the addition of extended wingtips and the position of a new bolt hole, did cause fatigue problems leading to the loss of two aircraft.[53]

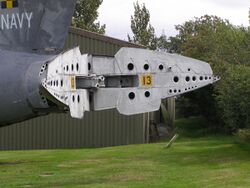

A large air brake formed the tail-cone of the aircraft. The hydraulically operated air brake formed two leaves that could be opened into the airstream to quickly decelerate the aircraft.[54] The style of air brake chosen by Blackburn was highly effective in the dive-attack profile that the Buccaneer was intended to perform, as well as effectively balancing out induced drag from operating the BLC system.[52] It featured a variable incidence tailplane that could be trimmed to suit the particular requirements of low-speed handling, or high-speed flight;[40] the tailplane had to be high mounted due to the positioning and functionality of the Buccaneer's air brake.[52]

The wing design of the Buccaneer was a compromise between two requirements: a low-aspect ratio for good gust response, and high-aspect ratio to give good range performance.[55] The small wing was suited to high-speed flight at low altitude; however, a small wing did not generate sufficient lift that was essential for carrier operations. Therefore, BLC was used upon both the wing and tailplane, having the effect of energising and smoothing the boundary layer airflow, which significantly reduced airflow separation at the back of the wing, and therefore decreased stall speed, and increased effectiveness of trailing edge control surfaces, including flaps and ailerons.[56] To extend the Buccanneer's operating life during the 1980s, it was deemed necessary to replace the original new spar rings on those aircraft that were retained.[57]

Operational history

Fleet Air Arm

The Buccaneer entered service with the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) on 17 July 1962, when 801 NAS was commissioned at RNAS Lossiemouth in Scotland.[58] The Buccaneer quickly replaced the FAA's Supermarine Scimitar, which had previously been performing the naval attack role.[59] In addition to conventional ordnance, the Buccaneer was cleared for nuclear weapons delivery in 1965; weapons deployed included Red Beard and WE.177 free-fall bombs, which were carried internally on a rotating bomb-bay door. Two FAA operational squadrons, and a training unit were equipped with the Buccaneer S.1. The aircraft was well liked by Navy aircrew for its strength and flying qualities, and the BLC system gave them slower landing speeds than they were accustomed to. The Buccaneers were painted dark sea grey on top, and anti-flash white on the undersides.[60]

Deficiences in the Buccaneer S.1's Gyron Junior engines led to the type's career coming to an abrupt end in December 1970.[13] On 1 December, an S.1 attempted to overshoot from a misjudged landing approach but one engine surged and produced no thrust, forcing the two crewmen to eject. On 8 December, an S.1 on a training flight suffered a massive uncontained engine failure. The pilot successfully ejected, but due to a mechanical failure in his ejection seat the navigator was killed. Subsequent inspections concluded that the Gyron Junior engine was no longer safe to fly. All remaining S.1s were grounded immediately and permanently.[61]

By April 1965, intensive trials of the new Buccaneer S.2 had begun, with the type entering operational service with the FAA later that year. The improved S.2 type proved its value when it became the first FAA aircraft to make a non-stop, unrefuelled crossing of the Atlantic Ocean.[62] On 28 March 1967, Buccaneers from RNAS Lossiemouth bombed the shipwrecked supertanker Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist. off the western coast of Cornwall to make the oil burn in an attempt to avoid an environmental disaster. In 1972, Buccaneers of 809 Naval Air Squadron operating from Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist. took part in a 1,500-mile (2,400 km) mission to show a military presence over British Honduras (now Belize) shortly before its independence, to deter a possible Guatemalan invasion in pursuit of its territorial claims over the country.[63]

The Buccaneer also participated in regular patrols and exercises in the North Sea, practising the type's role if war had broken out with the Soviet Union. During the 1960s and 1970s, the Royal Navy standardised the air wings operating from their carriers around the Phantom, Buccaneer, and the Fairey Gannet aircraft.[64] A total of six FAA squadrons were equipped with the Buccaneer: 700B/700Z (intensive flying trials unit), 736 (training), 800, 801, 803 and 809 Naval Air Squadrons. Buccaneers were embarked on HMS Victorious, Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist., HMS Ark Royal, and Script error: The function "ship_prefix_templates" does not exist..[65]

The Buccaneer was retired from FAA service with the decommissioning in February 1979 of the Ark Royal, the last of the navy's fleet carriers.[64] Their retirement was part of a larger foreign policy agenda that was implemented throughout the 1970s. Measures such as the withdrawal of most British military forces stationed East of Suez were viewed as reducing the need for aircraft carriers, and fixed-wing naval aviation in general. The decision was highly controversial, particularly to those within the FAA.[66] The Royal Navy would replace the naval strike capability of the Buccaneer with the smaller V/STOL-capable British Aerospace Sea Harrier, which were operated from their Script error: The function "sclass" does not exist.s.[67]

Royal Air Force

After the General Dynamics F-111K was cancelled in early 1968, due to the programme suffering serious cost escalation and delays, the RAF was forced to look for a replacement that was available and affordable, and reluctantly selected the Buccaneer.[68] The first RAF unit to receive the Buccaneer was 12 Squadron at RAF Honington in October 1969, in the maritime strike role, at first equipped with ex-Royal Navy Buccaneer S.2As.[69] This was to remain a key station for the type, as 15 Squadron equipped with the Buccaneer the following year, before moving to RAF Laarbruch in 1971, and the RAF Buccaneer conversion unit, No. 237 Operational Conversion Unit RAF, forming at Honington in March 1971.[69][70] The Buccaneer was seen as an interim solution, but delays in the Panavia Tornado programme would ensure that the 'interim' period would stretch out, and the Buccaneer would remain in RAF service for over two decades, long after the FAA had given up the type.[68]

With the phased withdrawal of the Royal Navy's carrier fleet during the 1970s, the Fleet Air Arm's Buccaneers were transferred to the RAF, which had taken over the maritime strike role.[71] 62 of the 84 S.2 aircraft were eventually transferred, redesignated S.2A;[68] some of these were later upgraded to S.2B standard. Ex-FAA aircraft equipped 16 Squadron, joining 15 Squadron at RAF Laarbruch, and 208 Squadron at Honington; the last ex-FAA aircraft went to 216 Squadron shortly before its disbandment.[69]

From 1970, with 12 Squadron initially, followed by 15 Squadron, 16 Squadron, No. 237 OCU, 208 Squadron, and 216 Squadron, the RAF Buccaneer force re-equipped with WE.177 nuclear weapons. At peak strength, Buccaneers equipped six RAF squadrons, although for only a year. A more sustained strength of five squadrons was made up of three squadrons (15 Squadron, 16 Squadron, 208 Squadron), plus No. 237 OCU (a war reserve or Shadow squadron), all assigned to Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) for land strike duties in support of land forces opposing Warsaw Pact forces in continental Europe, plus one squadron (12 Squadron) assigned to Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) for maritime strike duties.

Opportunities for Buccaneer squadrons to engage in realistic training were limited, and so when the US began its Red Flag (United States Air Force) military exercises at Nellis Air Force Base in 1975, the RAF became keenly interested. The first Red Flag in which RAF aircraft were involved was in 1977, with 10 Buccaneers and two Avro Vulcan bombers participating. Buccaneers would be involved in later Red Flags through to 1983, and in 1979, also participated in the similar Maple Flag exercise over Canada. The Buccaneer proved successful with its fast low-level attacks, which were highly accurate despite the lack of terrain-following radar and other modern avionics.

During the 1980 Red Flag exercises, one of the participating Buccaneers lost a wing mid-flight due to a fatigue-induced crack and crashed, killing its crew. The entire RAF Buccaneer fleet was grounded in February 1980; subsequent investigation discovered serious metal fatigue problems to be present on numerous aircraft.[72] A total of 60 aircraft were selected to receive new spar rings, while others were scrapped; the nascent 216 Squadron was subsequently disbanded due to a resulting reduction in aircraft numbers.[57] Later the same year, the UK-based Buccaneer squadrons moved to RAF Lossiemouth in order to free space at Honington for the Tornado.

In 1983, six Buccaneer S.2s were sent to Cyprus to support British peacekeepers in Lebanon as a part of Operation Pulsator. On 11 September 1983, two of these aircraft flew low over Beirut, their presence intended to intimidate insurgents, rather than inflict damage directly.[57][73] After 1983, the land strike duties were mostly reassigned to the Tornado aircraft then entering service, and two Buccaneer squadrons remaining (12 Squadron, and 208 Squadron) were then assigned to SACLANT for maritime strike duties. Only the 'Shadow Squadron', No. 237 OCU, remained assigned to the role of land strike on long term assignment to SACEUR, No. 237 was also to operate as a designator for Jaguar ground strike aircraft in the event of conflict.[74] The Buccaneer stood down from its reserve nuclear delivery duties in 1991.

The Buccaneer took part in combat operations during the 1991 Gulf War. It had been anticipated that Buccaneers might need to perform in the target designation role, although early on, this had been thought to be "unlikely".[74] Following a short-notice decision to deploy, the first batch of six aircraft were readied to deploy in under 72 hours, including the adoption of desert camouflage, and additional equipment, and departed from Lossiemouth for the Middle Eastern theatre early on 26 January 1991.[74] In theatre, it became common for each attack formation to comprise four Tornados and two Buccaneers; each Buccaneer carried a single laser designator pod, and acted as backup to the other in the event of an equipment malfunction.[74] The first combat mission took place on 2 February, operating at a medium altitude of roughly 18,000 feet (5,500 m), and successfully attacked the As Suwaira Road Bridge.[74]

Operations continued on practically every available day; missions did not take place at night as the laser pod lacked night-time functionality. Approximately 20 road bridges were destroyed by Buccaneer-supported missions, restricting the Iraqi Army's mobility and communications.[74] In conjunction with the advance of Coalition ground forces into Iraq, the Buccaneers switched to airfield bombing missions, targeting bunkers, runways, and any aircraft sighted; following the guidance of the Tornado's laser-guided ordnance, the Buccaneers would commonly conduct dive-bombing runs upon remaining targets of opportunity in the vicinity.[74] In one incident on 21 February 1991, a pair of Buccaneers destroyed two Iraqi transport aircraft on the ground at Shayka Mazhar airfield.[74] The Buccaneers flew 218 missions during the Gulf War, in which they designated targets for other aircraft, and dropped 48 laser-guided bombs.[75]

It had originally been planned for the Buccaneer to remain in service until the end of the 1990s, having been extensively modernized in a process lasting up to 1989; the end of the Cold War stimulated major changes in British defence policy, many aircraft being deemed to be surplus to requirements. It was decided that a number of Tornado GR1s would be modified for compatibility with the Sea Eagle missile, and take over the RAF's maritime strike mission, and the Buccaneer would be retired early.[76] Squadrons operating the Buccaneer were quickly re-equipped with the Tornado; by mid-1993, 208 Squadron was the sole remaining operator of the type.[57] The last Buccaneers were withdrawn in March 1994, when 208 Squadron disbanded.[77]

South African Air Force

South Africa was the only country other than the UK to operate the Buccaneer, where it was in service with the SAAF from 1965 to 1991. In January 1963, even before the S.2 entered squadron service, South Africa had purchased 16 Spey-powered Buccaneers. The order was part of the Simonstown Agreement, in which the UK obtained use of the Simonstown naval base in South Africa, in exchange for maritime weapons.[78] An order for a further 20 Buccaneers was blocked by British Prime Minister Harold Wilson's government.[79]

In the maritime strike role, SAAF Buccaneers were armed with the French radio-guided AS-30 missile. In March 1971, Buccaneers fired 12 AS-30s at a stricken tanker, the Wafra, but failed to sink it. The AS-30 missile was also used in ground attacks for effective precision strikes, one example being in 1981, when multiple missiles were used to strike a number of radar stations in southern Angola.[80] For overland attack, the SAAF Buccaneers carried up to four 1,000-pound (450 kg) bombs in the rotary bomb bay, and four bombs, flares, or SNEB rocket packs on the underwing stores pylons. During the 1990s, it was revealed that South Africa had manufactured six air-deliverable tactical nuclear weapons between 1978 and 1993. These nuclear weapons, containing highly enriched uranium, with an estimated explosion yield of 10-18 kilotons, were designed for delivery by either the Buccaneer or the Canberra bomber.[81]

SAAF Buccaneers saw active service in the 1970s and 1980s during the South Africa Border War, frequently flying over Angola and Namibia, launching attacks upon SWAPO guerilla camps. During a ground offensive, Buccaneers would often fly close air support (CAS) missions armed with anti-personnel rockets, as well as performing bombardment operations.[82] Buccaneers played a major role in the Battle of Cassinga in 1978, being employed in repeated strikes upon armoured vehicles, including enemy tanks, and to cover the withdrawal of friendly ground forces from the combat zone.[83] The Buccaneer was capable of carrying heavy load outs over a long range, and could remain in theatre for longer than other aircraft, making it attractive for the CAS role.[79] On 3 January 1988, Buccaneers of the SADF destroyed the important bridge across the Cuito River using a Raptor glide bomb, following on from a less successful attempt on 12 December 1987.[84] Only five aircraft remained operational by the time the Buccaneer was retired from service in 1991.[79]

Others

Early in the Buccaneer programme, the US Navy had expressed mild interest in the aircraft, but quickly moved on to the development of its comparable Grumman A-6 Intruder. The West German Navy showed a greater interest, and considered replacing its Hawker Sea Hawks with the type, although it eventually decided on the Lockheed F-104G for its maritime strike requirement, following the bribing of West German government officials in the Lockheed bribery scandals.

Variants

- Blackburn NA.39

- Pre-production build of nine prototype NA.39 aircraft, and a development batch of fourteen S.1s ordered 2 June 1955.[8]

- Buccaneer S.1

- First production model, powered by de Havilland Gyron Junior 101 turbojet engines. Forty built, ordered on 25 September 1959, built at Brough and towed to Holme-on-Spalding Moor for first flight and testing. First aircraft flown on 23 January 1962. A further ten S.1 aircraft ordered in September 1959 were completed as S.2s.

- Buccaneer S.2

- Development of the S.1 with various improvements, and powered by the more powerful Rolls-Royce Spey turbofan engines. From 1962, ten were built by Blackburn Aircraft Limited, and seventy-four by Hawker Siddeley Aviation Limited.[85]

- Buccaneer S.2A

- Ex-Royal Navy S.2 aircraft reworked for Royal Air Force.[86]

- Buccaneer S.2B

- Variant of S.2 for RAF squadrons. Capable of carrying the Martel anti-radar or anti-shipping missile. Forty-six built between 1973 and 1977, plus three for Ministry of Defence weapons trials work.[87]

- Buccaneer S.2C

- Royal Navy aircraft upgraded to S.2A standard.[28]

- Buccaneer S.2D

- Royal Navy aircraft upgraded to S.2B standard, operational with Martels from 1975.[28]

- Buccaneer S.50

- Variant for South Africa. Wings could be folded, but folding was no longer powered. Aircraft could be equipped with two Bristol Siddeley 605 single-stage RATO rockets to assist take-off from hot-and-high airfields like that of AFB Waterkloof in Pretoria, where the type was mostly based.[88]

Operators

South Africa

South Africa

- South African Air Force (SAAF)

- 24 Squadron SAAF formed at Lossiemouth in Scotland on 1 May 1965, training its crews before moving back to South Africa in November that year, being based at Waterkloof. It disbanded on 28 March 1991.[89]

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

- Royal Air Force (RAF)

- No. 12 Squadron RAF formed at RAF Honington on 1 October 1969, in an anti-shipping role. It moved to RAF Lossiemouth in Scotland in November 1980, and disbanded on 30 November 1993.[90]

- No. 15 Squadron RAF formed at Honington on 1 October 1970, moving to RAF Laarbruch in Germany in January 1971, operating in the overland strike role. It disbanded on 1 July 1983, handing its aircraft to 16 Squadron.[91]

- No. 16 Squadron RAF re-equipped from the Canberra B(I)8 at Laarbruch in October 1972. It discarded its Buccaneers on 29 February 1984, re-equipping with the Panavia Tornado.[91]

- No. 208 Squadron RAF reformed at Honington on 1 July 1974 in the strike role. It switched its primary mission to anti-shipping in 1983, moving to Lossiemouth in July that year. It disbanded on 31 March 1994, the last of the RAF's Buccaneer squadrons.[92]

- No. 216 Squadron RAF formed at Honington on 1 July 1979, with the intended role of anti-shipping operations. When the Buccaneer was grounded in 1980, the Squadron handed its aircraft to 12 Squadron without becoming operational.[92]

- No. 237 Operational Conversion Unit RAF formed at RAF Honington on 1 March 1971 as the Operational Conversion Unit for the Buccaneer. In 1984, it gained the additional role of laser designation support for Royal Air Force Germany (RAFG), and moved north to Lossiemouth in October 1984. The OCU disbanded on 1 October 1991, with training duties for the Buccaneer being handled by 208 Squadron.[93]

- Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm (FAA)

- 700Z/700B Naval Air Squadron (S.1 and S.2 Intensive Flying Trials Units, respectively)[94]

- 736 Naval Air Squadron formed on 29 March 1965 as the Fleet Air Arm Buccaneer training squadron when 809 Squadron disbanded. It disbanded on 25 February 1972, with the task of training Buccaneer crews for the Fleet Air Arm transferred to 237 OCU.[95]

- 800 Naval Air Squadron commissioned on 18 March 1964, serving aboard HMS Eagle. It disbanded on 23 February 1972.[95]

- 801 Naval Air Squadron commissioned on 17 July 1962 as the Fleet Air Arm's first Buccaneer squadron. It made one shakedown deployment on HMS Ark Royal, before being assigned to HMS Victorious. After Victorious was retired following a fire in 1967, 801 Naval Air Squadron was assigned to HMS Hermes, disbanding on 21 July 1970.[96]

- 803 Naval Air Squadron commissioned on 3 July 1967 at Lossiemouth as the Buccaneer trials and headquarters squadron, disbanding on 18 December 1969.[96]

- 809 Naval Air Squadron commissioned on 15 January 1963 as the Buccaneer headquarters and training squadron. It disbanded in March 1965, when it was renumbered as 736 Naval Air Squadron. It reformed in January 1966 as an operational squadron equipped with the Buccaneer S.2, deploying on HMS Hermes in 1967–68, and on HMS Ark Royal from 1970 until the carrier decommissioned in 1979. It disbanded on 15 December 1978.[97]

Civil operators

At one point, a total of three privately owned Buccaneers were being operated at Thunder City.[98]

Surviving aircraft

In the United Kingdom, Buccaneer S.2 XX885 has been rebuilt to flying condition by Hawker Hunter Aviation. It was granted UK CAA permission to fly in April 2006.[99][100]

Five Buccaneers in the UK (XN923, XN974, XW544, XX894 and XX900) are in fast taxiing condition.[101][102]

Specifications (Buccaneer S.2)

Data from The Observer's Book of Aircraft,[103] Aeroguide 30: Blackburn Buccaneer S Mks. 1 and 2[104]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 63 ft 5 in (19.33 m)

- Wingspan: 44 ft (13 m)

- Height: 16 ft 3 in (4.95 m)

- Wing area: 514 sq ft (47.8 m2)

- Empty weight: 30,000 lb (13,608 kg)

- Gross weight: 62,000 lb (28,123 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Rolls-Royce Spey Mk.101 turbofan engines, 11,000 lbf (49 kN) thrust each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 580 kn (670 mph, 1,070 km/h) at 200 ft (61 m)

- Maximum speed: Mach 0.95

- Range: 2,000 nmi (2,300 mi, 3,700 km)

- Service ceiling: 40,000 ft (12,000 m)

- Wing loading: 120.5 lb/sq ft (588 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.36

Armament

- Hardpoints: 4 × under-wing pylon stations for up to 12,000 lb (5,443 kg) of bombs, and 1 × internal rotating bomb bay with a capacity of 4,000 lb (1,814 kg),with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets: 4 × Matra rocket pods with 18 × SNEB 68-mm rockets each

- Missiles: Either 2 × AIM-9 Sidewinders for self-defence, 3 × AS-37 Martel missiles, 2x AJ-168 TV Martel,or 3 × Sea Eagle missile

- Bombs: Various unguided bombs, laser-guided bombs, as well as either the Red Beard or WE.177 tactical nuclear bombs

- Other: AN/ALQ-101 ECM protection pod, AN/AVQ-23 Pave Spike laser designator pod, buddy refuelling pack or drop tanks for extended range/loitering time

Avionics

Blue Parrot ASV search/attack radar

Notable appearances in media

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Related lists

- List of aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm

- List of attack aircraft

References

Citations

- ↑ "Blackburn Buccaneer". BAE Systems. https://www.baesystems.com/en-uk/heritage/blackburn-buccaneer.

- ↑ Jackson 2011, p. 137.

- ↑ Jefford et al. 2005, pp. 103-104.

- ↑ Chesneau 2005, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ English Aeroplane April 2012, p. 72.

- ↑ Jackson 1968, p. 480.

- ↑ Jackson 1968, p. 481.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Chesneau 2005, pp. 6–8.

- ↑ Jefford et al. 2005, p. 104.

- ↑ Green 1964, p. 430.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 48.

- ↑ Bishop and Chant 2004, p. 162.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Jackson 1968, pp. 487–488.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Flight International 11 January 1962, p. 38.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Jefford et al. 2005, p. 105.

- ↑ Eeles 2008, pp. 61-64.

- ↑ "British to sell jets to Africa." Spokane Daily Chronicle, 12 October 1962. p. 10.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, pp. 51–53.

- ↑ Van Pelt 2012, p. 180.

- ↑ Laming 1996, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Wynn 1997, p. 503.

- ↑ Buttler Air Enthusiast September/October 1995, pp. 12–13, 15–16, 21–23.

- ↑ Boot Aeroplane Monthly March 1995, p. 29.

- ↑ Wynn Flight International 11 February 1971, p. 203.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Boot 1990, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 Chesneau 2005, p. 16.

- ↑ "RAF plans Buccaneer update." Flight International, 4 February 1984. p. 316.

- ↑ Hampshire 2013, p. 60.

- ↑ Hampshire 2013, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Gunston 1974, p. 33.

- ↑ Boot 1990, p. 85.

- ↑ Eeles 2008, pp. 41-42.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Polmar 2006, p. 184.

- ↑ Gunston 1962, pp. 475, 478.

- ↑ Gunston 1962, p. 477.

- ↑ Gunston 1962, p. 479.

- ↑ "Thunder & Lightnings - Blackburn Buccaneer - History". https://www.thunder-and-lightnings.co.uk/buccaneer/history.php.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Winchester 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ Polmar 2006, p. 186.

- ↑ "[SAAF Buccaneer H-2 Raptor Weapon Pack"]. https://www.shapeways.com/product/SGXCN6WBC/buccaneer-h-2-raptor-weapon-pack. "This weapon system was used by Buccaneers in the South-African Air Force (SAAF) in the late 1980's in the final phases of the South-African involvement in the Angolan conflict: 2x H2 Raptor Glide Bombs, 1x Communications Pod, 1x ELT-555 ECM Pod"

- ↑ Gunston 1962, p. 478.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 14.

- ↑ Jefford et al. 2005, pp. 113-114.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Gunston 1962, p.469.

- ↑ Harding 2004, p. 85.

- ↑ Burns and Edwards 1971, pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Burns, J.G.; Edwards, M. (14 January 1971). "Blow, Blow Thou BLC Wind". Flight International (Flight Global) 99 (3227): 56–59. https://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1971/1971%20-%200061.html. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ↑ Flight International 14 January 1971, p. 58.

- ↑ Burns and Edwards 1971, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 Gunston 1962, p. 468.

- ↑ Boot 1990, p. 181.

- ↑ Boot Aeroplane Monthly March 1995, p. 26.

- ↑ Flight International 14 January 1971, p. 56.

- ↑ Laming 1996, p. 11.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 Chesneau 2005, p. 22.

- ↑ "Buccaneer Enters Service Today." Times [London, England], 17 July 1962: 6 via The Times Digital Archive, 3 May 2013.

- ↑ Chesneau 2005, p. 9.

- ↑ Chesneau 2005, p. 24.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 62.

- ↑ Chesneau 2005, p. 12.

- ↑ White 2009, p. 242.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Bishop and Chant 2004, p. 115.

- ↑ Bishop and Chant 2004, pp. 65, 71–72, 74.

- ↑ Jefford et al. 2005, p. 61.

- ↑ Ford, Terry. "Sea Harrier – A New Dimension." Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology, Volume 53, Issue 6, 1981.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 Laming 1996, p.12.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Chesneau 2005, p. 21.

- ↑ English Aeroplane April 2012, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ Jefford et al. 2005, pp. 105-106.

- ↑ Chesneau 2005, pp. 16, 22.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 84.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 74.5 74.6 74.7 Cope, Bill. "Gulf War Buccaneer Operations." Royal Air Force, Retrieved: 8 May 2013.

- ↑ Gething 1994, pp. 143–144.

- ↑ Jefford et al. 2005, p. 115.

- ↑ Jefford 2001, p. 72.

- ↑ "Simonstown Agreement." Hansard, 8 February 1967.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 Caygill 2008, p.70.

- ↑ "SA-30 Air-to-Surface Missile." SAAF Museum, Retrieved: 19 May 2013.

- ↑ "Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI)." Nuclear Disarmament South Africa. Retrieved: 11 June 2012.

- ↑ Steenkamp 2006, pp. 151-153, 164.

- ↑ Steenkamp 2006, pp. 178-179, 187.

- ↑ Scholtz 2013, p. 330.

- ↑ Chesneau 2005, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Chesneau 2005, p. 14.

- ↑ Chesneau 2005, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Chesneau 2005, p. 18.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p.103.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 98.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 99.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 100.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 101.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 94.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 95.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 96.

- ↑ Calvert and Donald Wings of Fame Volume 14, p. 97.

- ↑ "BAe 2 Buccaneer." ThunderCity, 2010.

- ↑ White, Andy. "CAA Approval to Fly! XX885 (G-HHAA) To Return to the Sky." blackburn-buccaneer.co.uk, 12 April 2006. Retrieved: 7 October 2009.

- ↑ Scott, Richard "Hawker Hunter Aviation's new model air force." Flight International, 17 December 2007.

- ↑ White, Andy. "XX894." blackburn-buccaneer.co.uk, 5 April 2009. Retrieved: 7 October 2009.

- ↑ White, Andy. "XW544." blackburn-buccaneer.co.uk, 5 April 2009. Retrieved: 7 October 2009.

- ↑ Green 1968, p. 136.

- ↑ Chesneau 2005, p. 13.

Bibliography

- Bishop, Chris and Chris Chant. Aircraft Carriers: The World's Greatest Naval Vessels and Their Aircraft. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Zenith Imprint, 2004. ISBN 0-76032-005-5.

- Boot, Roy. "Father of the Buccaneer". Aeroplane Monthly, Vol. 23, No. 3, March 1995,. pp. 24–29. ISSN 0143-7240.

- Boot, Roy. From Spitfire to Eurofighter: 45 Years of Combat Aircraft Design. Shrewsbury, Shropshire, UK: Airlife Publishing Ltd., 1990. ISBN 1-85310-093-5.

- Burns, J.G. and M. Edwards. "Blow, blow thou BLC wind". Flight International Vol. 99, No. 3227, 14 January 1971, pp. 56–59.

- Buttler, Tony. "Strike Rivals: The ones that 'lost' when the TSR.2 'won'." Air Enthusiast, No. 59, September/October 1995, pp. 12–23.

- Calvert, Denis J. and David Donald. "Blackburn Buccaneer". Wings of Fame, Volume 14. London: Aerospace Publishing, 1999. pp. 34–103. ISBN 1-86184-029-2. ISSN 1361-2034.

- Caygill, Peter. "Flying the Buccaneer: Britain's Cold War Warrior." Casemate Publishers, 2008. ISBN 1-84415-669-9.

- Chesneau, Roger. "Aeroguide 30 - Blackburn Buccaneer S Mks 1 and 2". Suffolk, UK: Ad Hoc Publications, 2005. ISBN 0-94695-840-8.

- Eeles, Tom (2008). A Passion For Flying 8000 hours of RAF Flying. Pen $ Sword Books Ltd. ISBN 978 1 84415 688 7.

- English, Malcolm. "Database: Blackburn (Hawker Siddeley) Buccaneer". Aeroplane, Vol. 40, No. 4, April 2012, pp. 69–86.

- Gething, Michael J. "The Buccaneer Bows Out: Valediction for the Sky Pirate". Air International, Vol. 46, No 3, March 1994, pp. 137–144. Stamford, UK: Key Publishing. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Green, William. Aircraft Handbook. London: Macdonald & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., 1964.

- Green, William. The Observer's Book of Aircraft. London: Frederick Warne & Co. Ltd., 1968.

- Gunston, Bill (4 April 1963). "Buccaneer - An Outstanding Strike Aeroplane". Flight International 83 (2821): 467–478. http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1963/1963%20-%200489.html.

- Gunston, Bill (1974). Attack Aircraft of the West. Ian Allan Ltd. ISBN 0 7110 0523 0.

- Hampshire, Edward. From East of Suez to the Eastern Atlantic: British Naval Policy 1964-70. Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2013. ISBN 1-40946-614-0.

- Harding, Richard. The Royal Navy 1930-1990: Innovation and Defense. London: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0-20333-768-9.

- Jackson, A.J. Blackburn Aircraft since 1909. London: Putnam, 1968. ISBN 0-370-00053-6.

- Jackson, Robert (2011). Aircraft from 1914 to the present day. ISBN 978-1-907446-02-3.

- Jefford, C.G. RAF Squadrons, a Comprehensive Record of the Movement and Equipment of all RAF Squadrons and their Antecedents since 1912. Shrewsbury, Shropshire, UK: Airlife Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1-84037-141-2.

- Jefford, C.G (ed.). "Seminar - Maritime Operations." Royal Air Force Historical Society, 2005. ISSN 1361-4231.

- Laming, Tim. Fight's On!: Airborne with the Aggressors. Zenith Imprint, 1996. ISBN 0-76030-260-X.

- Polmar, Norman. Aircraft Carriers: A History of Carrier Aviation and Its Influence on World Events, Volume I: 1909-1945. Herndon, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2006. ISBN 1-57488-663-0.

- Scholtz, Leopold (2013). The SADF in the Border War 1966–1989. Cape Town: Tafelberg (NB Publishers) (published 15 May 2013). ISBN 9780624054108. http://www.nb.co.za/Books/14632. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- Steenkamp, Willem. Borderstrike!: South Africa into Angola 1975-1980 (3rd ed.). Durban, South Africa: Just Done Productions Publishing, 2006first edition 1985. ISBN 978-1-920169-00-8.

- Van Pelt, Michel. Rocketing into the Future: The History and Technology of Rocket Planes. New York: Springer, 2012. ISBN 1-46143-200-6.

- White, Rowland. Phoenix Squadron: HMS Ark Royal, Britain's Last Topguns and the Untold Story of Their Most Dramatic Mission. London: Bantam Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-59305-451-2.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. "Blackburn Buccaneer." Military Aircraft of the Cold War (The Aviation Factfile). London: Grange Books plc, 2006. ISBN 1-84013-929-3.

- Wynn, Humphrey. "RAF Buccaneers". Flight International, 11 February 1971, Vol. 99 No. 3231, pp. 202–207.

- Wynn, Humphrey. The RAF Strategic Nuclear Deterrent Forces: Their Origins, Roles and Deployment, 1946-1969: a Documentary History. London: HMO, 1997. ISBN 0-11772-833-0.

External links

- Blackburn Buccaneer from Thunder and Lightnings

- The Blackburn Buccaneer at Air Vectors

- Blackburn Buccaneer: The awesome "Banana" Jet

- The FAA Buccaneer Association

- "NA.39 - Blackburn's Naval Bomber: A First Analytical Study" a 1958 Flight article by Bill Gunston

- "Flying the Buccaneer" a 1962 Flight article

- "1995 documentary about the Buccaneer's career"

- Destruction of the Cuito River bridge on 3 January 1988 by a SAAF Buccaneer

|