Engineering:Bresse house

A Bresse house[1] (French: ferme bressane or maison bressane, German: Bressehaus) is a timber-framed house of post-and-beam construction, that is infilled with adobe bricks and is typical of the Bresse region of eastern France . A large hip roof protects the delicate masonry from rain and snow. The house is almost always oriented in a north–south direction, the roof on the north side often being lower. This configuration offers the optimum protection from the bise, a cold northerly wind typical of the region, which is deflected over the house by the low, sweeping roof on the northern gable end. The living rooms are on the south side, the main façade facing the morning sun. Usually each room has one or two outside doors, so that no space is sacrificed for passages.

The large cantilevered roof is supported on corbels or buttresses, the eaves being further supported on a second set of shorter rafters, resulting in a double-pitched roof. The eaves enable equipment or supplies to be stored around the outside of the house and kept dry. They also enable corn cobs to be hung from the rafters to dry out.

The countryside of the Bresse is characterized by agricultural buildings; the villages often suffer from overdevelopment; the farmsteads are usually far from these villages, by lakes, streams, woods and where possible on slight eminences.

Features

Timber framing

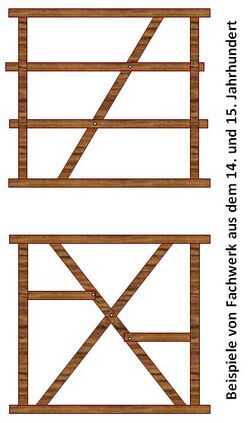

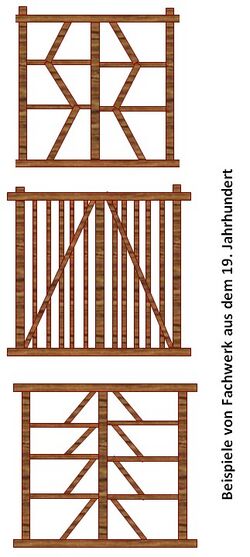

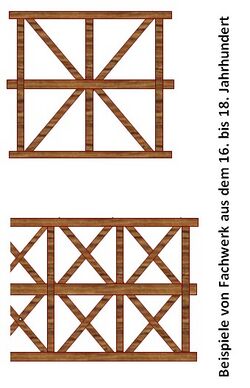

Whilst the timber framing of the 14th and 15th centuries was still simple and large-scale, in the 16th to 18th centuries ever more complicated designs evolved, on one hand to give the building greater stability, and on the other for decorative reasons. Especially popular were crossed struts that formed a St. Andrew's Cross. Timber-framed buildings continued to be erected until the mid-19th century. Then there was a change: in the southern Bresse rammed earth (Stampflehm) was increasingly used for the walls, which usually had reinforced corners of brick or stone, and the façades were covered with rammed earth. In the northern Bresse, brick has generally been used since the 19th century, albeit bricks of low quality. At the same time, the hips on the gable ends were shortened to create a half-hipped roof or even a simple gable roof, with the eaves on the gable ends disappearing almost completely.

Farmstead forms

Two forms of farmstead predominated. On the one hand there was the unit farmhouse,[2] which was partitioned transversely and where, in most cases, the threshing floor was in the middle of the house; on the other hand there was the two-sided farm with the farmhouse on one side and outbuildings on the other. The main farmhouse was usually oriented in a north–south direction, but there were often variations in which the building was oriented northeast to southwest. When erecting the houses, builders appear to have taken account of the direction of the sun, in particular to ensure that the morning sun shone into the living rooms. As construction activity took place mainly in winter, outside the busy summer season, there was often a deviation in alignment. Very rarely, buildings oriented from northwest to southeast may be found.[3]

The farmstead consisted of at least three areas:

- Living quarters

- Stables and fodder store (threshing floor)

- Bakehouse with pigsty and chicken coop

There could be separate buildings for each of these functions, or the living quarters, fodder store and stables could be arranged one after another to form an elongated building. The living quarters were usually found along the western side of the farmyard. Where the buildings were separate, the threshing barn and stables would be built in succession along the eastern side of the yard. The bakehouse and quarters for the smaller livestock were usually found in the northeastern part of the farm. In southeastern Bresse, properties were occasionally built to an angular design.

Farmhouse

Living room

The main room of the farmhouse was called la maison in the south, le hutau in the north. This part of the house was regularly built of natural or fired bricks, the floor was made of packed earth. It was the largest room and served as the centre of life for the whole family. It was heated, originally with a Saracen fireplace (cheminée sarrasine), later with an open fireplace (cheminée à hotte). This room was generally quite large, often measuring 4m x 4m in area just by the fireplace. There were beds in the corners and simple boxes for personal belongings. A long, narrow oak table stood in the centre of the room under the ridge purlin from which the spoons and forks hung. Against the narrow wall behind the Saracen fireplace stood the bench (archebanc), which was solemnly blessed when the house was moved into. The windows were small, at most they had wooden shutters, they were seldom glazed. A little light also fell through the Saracen chimney, along with rain and snow. A corner of the room was reserved for the chapel, a kind of domestic altar, with a simple figure of Mary, a stoup, a candle or two, images of saints and patriotic prints. The house altar was regularly whitewashed on the eve of Kermesse.

Saracen fireplace (cheminée sarrasine)

The Saracen fireplace was an open fireplace of substantial size, which was heated in the centre of the hearth. In addition, the chimneys above the roof were adorned with picturesque decorations. The living room was bisected by the ridge purlin, the fireplace placed in one half of the room. A huge, inverted funnel, attached to the ridge and middle purlins, acted as a flue. It was also made of wood that was filled and daubed with clay. The flue began in the living room and extended in a funnel shape to the roof, where it merged into the picturesque mitra (chimney). The open fireplace was widespread throughout Europe in the Middle Ages and up to the end of the 19th century and was nothing unusual. The origin of the mitra and the term 'Saracenic' have not been clarified, however, it is only commonly found in the Bresse region. It is not clear whether it was actually used by the swaggering Saracens and brought to the Bresse in the 8th-12th centuries or whether it was a building feature brought back from the Crusades. The term Saracen means 'not Christian' and is equivalent to the Latin barbarus.

Stove chamber

Next to the living room there was always a second room, the stove chamber or la chambre de poêle. The family lived there in winter, since the room was heated by the next-door fireplace, but was enclosed and itself had no fireplace opening through which the cold could penetrate. If the family had servants and maids, the living room was reserved for them as a bedroom, while the master's family slept in the stove room. If the family had no employees, there was often a move twice a year from the living room into the stove room as a winter quarter and back to the living room as a summer residence. Many simple Bresse houses only had these two rooms.

Maids' room

If the house had several rooms, the stove chamber was adjoined by the maid's room. Wall to wall with the parents, it enabled care and parental supervision, especially since the maids' room was often only accessible via the stove room and had no outside door of its own.

Farm hands' room

The farm hands and maids always lived in the living room, but if the house was spacious and the family was wealthy, they were allocated a room next to the living room - opposite the maids' room.

Parents' room

The grandparents' room was often in an annex or squeezed in between the other utility rooms. This usance shows how high esteem was for the older family members of a poor farming family who were no longer able to work.

Outbuildings

The well was a fundamental part of the Bresse house. Some could reach a depth of up to 25 metres depending on the circumstances. The bakehouse is also an integral part of the Bresse house. Depending on the level of prosperity, a Bresse house may be supplemented with outbuildings or extensions. These include sheds, chicken coops, pigeon lofts or sheep and goat pens.

Stables

The stables may be a separate building parallel to the residential building, about 20 to 30 metres away to reduce the risk of fire. They are generally low and may have infills of twigs covered with clay, or infills of natural or baked adobe bricks. Hay and straw are stored under the large roof. In the southeast of the Bresse region, the stables are often attached to the house at right angles and thus form an angular building.

Bakehouse

The bakehouse is always a separate building, often combined with the pigsty and/or chicken coop. This allows pig feed to be prepared in the bakehouse. The bakehouse consists – especially in northern Bresse – of a double building: On one side is the rather spacious bakehouse; on the other, the oven is attached directly to it in a slightly lower annex. The chimney rises between the two parts of the building.

Well

The well has always been of great importance in Bresse, which has few springs and potable surface water. On the other hand, drinking water can be found relatively close to the surface almost everywhere. The well was usually covered, at least by a roof overhang or sometimes by a separate roof. Long balancing poles with counterweights were originally common in northern Bresse, but today the wells are all equipped with cranks and chains.

Regional differences

Due to the historical division of the Bresse into the Bresse bourguignonne and the Bresse de l'Ain, the architectural styles of the farmhouses have developed differently. From Cuisery the border runs south of Louhans, via Sagy to the Jura. The construction of the walls remains the same, but there are differences in the shape of the roof. In the Bresse bourguignonne region the roofs are usually steep and high and covered with flat tiles, while in the southern Bresse the roof is flatter (< 25% slope) and covered with monk and nun tiles. Older Bressans still remember that in their youth the majority of the farms were thatched.

Characteristic of a Bresse house in northern Bresse is the roof decoration. Very often a small brick tower or a finial is attached at the crossing point of the roof ridge and hip, but often the ridge is also decorated along its entire length.

In the border area with the Jura, the house is often built of natural stone, mainly broken limestone, which can be easily obtained from the Jura. In some cases, at least the corners of the house are made of stone to increase stability. In the area towards the Mâconnais and the Chalonnais, the courtyard becomes more enclosed and one often encounters courtyard farms enclosed by a wall. The street is reached through a portal.

In the marshy region of Bellevesvre and Beauvernois, small, squalid huts on stilts existed until the 1930s. These served as dwellings for the frog catchers. It is said that the last of these houses was demolished in 1931.[5]

References

- ↑ Monmarché, Georges (1949). France, Les Guides Bleu, English series, Nagel, p. 170.

- ↑ Base Mérimée: Ferme, Frontenard, 12 rue de la Motte, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ↑ Untersuchungen in Romenay und in den Kantonen Saint-Germain-du-Bois und Pierre-de-Bresse, gemäß L'Habitation paysanne en Bresse. p. 39.

- ↑ Base Mérimée: Ferme de Sougey, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ↑ L'Habitation paysanne en Bresse. pp. 38 & 43.

Sources

- G. Jeanton, A. Duraffour: L'Habitation paysanne en Bresse. 2. Auflage. Verlag Société des Amis des Arts et des Sciences de l'Arrondissement de Louhans, 1993.

|