Engineering:Form factor (electronics)

In electronics or electrical engineering the form factor of an alternating current waveform (signal) is the ratio of the RMS (root mean square) value to the average value (mathematical mean of absolute values of all points on the waveform).[1] It identifies the ratio of the direct current of equal power relative to the given alternating current. The former can also be defined as the direct current that will produce equivalent heat.[2]

Calculating the form factor

For an ideal, continuous wave function over time T, the RMS can be calculated in integral form:[3]

The rectified average is then the mean of the integral of the function's absolute value:[3]

The quotient of these two values is the form factor, , or in unambiguous situations, .

reflects the variation in the function's distance from the average, and is disproportionately impacted by large deviations from the unrectified average value.[4] It will always be at least as large as , which only measures the absolute distance from said average. The form factor thus cannot be smaller than 1 (a square wave where all momentary values are equally far above or below the average value; see below), and has no theoretical upper limit for functions with sufficient deviation.

can be used for combining signals of different frequencies (for example, for harmonics[2]), while for the same frequency, .

As ARV's on the same domain can be summed as , the form factor of a complex wave composed of multiple waves of the same frequency can sometimes be calculated as

.

Application

AC measuring instruments are often built with specific waveforms in mind. For example, many multimeters on their AC ranges are specifically scaled to display the RMS value of a sine wave. Since the RMS calculation can be difficult to achieve digitally, the absolute average is calculated instead and the result multiplied by the form factor of a sinusoid. This method will give less accurate readings for waveforms other than a sinewave, and the instruction plate on the rear of an Avometer states this explicitly. [5]

The squaring in RMS and the absolute value in ARV mean that both the values and the form factor are independent of the wave function's sign (and thus, the electrical signal's direction) at any point. For this reason, the form factor is the same for a direction-changing wave with a regular average of 0 and its fully rectified version.

The form factor, , is the smallest of the three wave factors, the other two being crest factor and the lesser-known averaging factor .

Due to their definitions (all relying on the Root Mean Square, Average rectified value and maximum amplitude of the waveform), the three factors are related by ,[2] so the form factor can be calculated with .

Specific form factors

represents the amplitude of the function, and any other coefficients applied in the vertical dimension. For example, can be analyzed as . As both RMS and ARV are directly proportional to it, it has no effect on the form factor, and can be replaced with a normalized 1 for calculating that value.

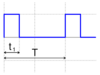

is the duty cycle, the ratio of the "pulse" time (when the function's value is not zero) to the full wave period . Most basic wave functions only achieve 0 for infinitely short instants, and can thus be considered as having . However, any of the non-pulsing functions below can be appended with

to allow pulsing. This is illustrated with the half-rectified sine wave, which can be considered a pulsed full-rectified sine wave with , and has .

| Waveform | Image | RMS | ARV | Form Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

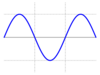

| Sine wave |  |

[2] | [2] | [3] |

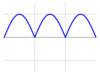

| Half-wave rectified sine |  |

|||

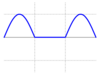

| Full-wave rectified sine |  |

|||

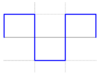

| Square wave, constant value |  |

|||

| Pulse wave |  |

[6] | ||

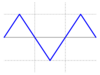

| Triangle wave |  |

[7] | ||

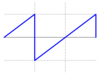

| Sawtooth wave |  |

|||

| Uniform random noise U(-a,a) |

References

- ↑ Stutz, Michael. "Measurement of AC Magnitude". BASIC AC THEORY. http://www.allaboutcircuits.com/vol_2/chpt_1/3.html. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Dusza, Jacek; Grażyna Gortat; Antoni Leśniewski (2002) (in Polish). Podstawy Miernictwa (Foundations of Measurement). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Politechniki Warszawskiej. pp. 136–142, 197–203. ISBN 83-7207-344-9.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Jędrzejewski, Kazimierz (2007) (in Polish). Laboratorium Podstaw Pomiarow. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Politechniki Warszawskiej. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-978-83-7207-3.

- ↑ "Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)". The European Virtual Organisation for Meteorological Training. http://www.eumetcal.org/resources/ukmeteocal/verification/www/english/msg/ver_cont_var/uos3/uos3_ko1.htm. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ↑ Tanuwijaya, Franky. "True RMS vs AC Average Rectified Multimeter Readings when a Phase Cutting Speed Control is Used". Esco Micro Pte Ltd. http://www.escoglobal.com/resources/pdf/white-papers/True_G2.pdf. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ↑ Nastase, Adrian. "How to Derive the RMS Value of Pulse and Square Waveforms". http://masteringelectronicsdesign.com/how-to-derive-the-rms-value-of-pulse-and-square-waveforms/. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- ↑ Nastase, Adrian. "How to Derive the RMS Value of a Triangle Waveform". http://masteringelectronicsdesign.com/how-to-derive-the-rms-value-of-a-triangle-waveform/. Retrieved 9 June 2012.