Engineering:Locky

| Aliases |

|

|---|---|

| Type | Trojan |

| Subtype | Ransomware |

| Author(s) | Necurs |

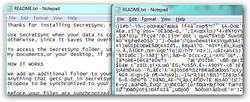

Locky is ransomware malware released in 2016. It is delivered by email (that is allegedly an invoice requiring payment) with an attached Microsoft Word document that contains malicious macros.[1] When the user opens the document, it appears to be full of gibberish, and includes the phrase "Enable macro if data encoding is incorrect," a social engineering technique. If the user does enable macros, they save and run a binary file that downloads the actual encryption Trojan, which will encrypt all files that match particular extensions. Filenames are converted to a unique 16 letter and number combination. Initially, only the .locky file extension was used for these encrypted files. Subsequently, other file extensions have been used, including .zepto, .odin, .aesir, .thor, and .zzzzz. After encryption, a message (displayed on the user's desktop) instructs them to download the Tor browser and visit a specific criminal-operated Web site for further information.

The website contains instructions that demand a ransom payment between 0.5 and 1 bitcoin (as of November 2017, one bitcoin varies in value between $9,000 and $10,000 via a bitcoin exchange). Since the criminals possess the private key and the remote servers are controlled by them, the victims are motivated to pay to decrypt their files.[2][3][4] Cryptocurrencies are very difficult to trace and are highly portable.[5]

Operation

The most commonly reported mechanism of infection involves receiving an email with a Microsoft Word document attachment that contains the code. The document is gibberish, and prompts the user to enable macros to view the document. Enabling macros and opening the document launch the Locky virus.[6] Once the virus is launched, it loads into the memory of the users system, encrypts documents as hash.locky files, installs .bmp and .txt files, and can encrypt network files that the user has access to.[7] This has been a different route than most ransomware since it uses macros and attachments to spread rather than being installed by a Trojan or using a previous exploit.[8]

Updates

On June 22, 2016, Necurs released a new version of Locky with a new loader component, which includes several detection-avoiding techniques, such as detecting whether it is running within a virtual machine or within a physical machine, and relocation of instruction code.[9]

Since Locky was released there have been numerous variants released that used different extensions for encrypted files. Many of these extensions are named after gods of Norse and Egyptian mythology. When first released, the extension used for encrypted files was .Locky. Other versions utilized the .zepto, .odin, .shit, .thor, .aesir, and .zzzzz extensions for encrypted files. The current version, released in December 2016, utilizes the .osiris extension for encrypted files.[10]

Distribution methods

Many different distribution methods for Locky have been used since the ransomware was released. These distribution methods include exploit kits,[11] Word and Excel attachments with malicious macros,[12] DOCM attachments,[13] and zipped JS attachments.[14]

The general consensus among security experts to protect yourself from ransomware, including Locky, is to keep your installed programs updated and to only open attachments from known senders.

Encryption

The Locky uses RSA-2048 + AES-128 cipher with ECB mode to encrypt files. Keys are generated on the server side, making manual decryption impossible, and Locky ransomware can encrypt files on all fixed drives, removable drives, network and RAM disk drives.[15]

Prevalence

Locky is reported to have been sent to about a half-million users on February 16, 2016, and for the period immediately after the attackers increased their distribution to millions of users.[16] Despite the newer version, Google Trend data indicates that infections have dropped off around June 2016.[17]

Notable incidents

On February 18, 2016, the Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center paid a $17,000 ransom in the form of bitcoins for the decryption key for patient data.[18] The hospital was infected by the delivery of an email attachment disguised as a Microsoft Word invoice.[19] This has led to increased fear and knowledge about ransomware in general and has brought ransomware into public spotlight once again. There appears to be a trend in ransomware being used to attack hospitals and it appears to be growing. [20]

On May 31, Necurs went dormant, perhaps due to a glitch in the C&C server.[citation needed][original research?] According to Softpedia, there were less spam emails with Locky or Dridex attached to it. On June 22, however, MalwareTech discovered Necurs's bots consistently polled the DGA until a C&C server replied with a digitally signed response. This signified Necurs was no longer dormant. The cybercriminal group also started sending a very large quantity of spam emails with new and improved versions of Locky and Dridex attached to them, as well as a new message and zipped JavaScript code in the emails.[9][21]

In Spring 2016, the Dartford Grammar School and Dartford Science & Technology College computers were infected with the virus. In both schools, a student had opened an infected email which quickly spread and encrypted many school files. The virus stayed on the computer for several weeks. Eventually, they managed to remove the virus by using System Restore for all of the computers.

Spam email vector

An example message with Locky as an attachment is the following:

Dear (random name):

Please find attached our invoice for services rendered and additional disbursements in the above-mentioned matter.

Hoping the above to your satisfaction, we remain

Sincerely,

(random name)

(random title)

References

- ↑ Sean Gallagher (February 17, 2016). ""Locky" crypto-ransomware rides in on malicious Word document macro". arstechnica. https://arstechnica.com/security/2016/02/locky-crypto-ransomware-rides-in-on-malicious-word-document-macro/.

- ↑ "locky-ransomware-what-you-need-to-know". https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2016/02/17/locky-ransomware-what-you-need-to-know/. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "locky ransomware". 6 April 2016. https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/Locky-Ransomware-Cybercriminals-Introduce-New-RockLoader-Malware. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "Locky ransomware: How this malware menace evolved in just 12 months" (in en). https://www.zdnet.com/article/locky-ransomware-how-this-malware-menace-evolved-in-just-12-months/.

- ↑ Ryan, Matthew (2021-02-24) (in en). Ransomware Revolution: The Rise of a Prodigious Cyber Threat. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-66583-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=VBwgEAAAQBAJ&dq=what+happened+to+locky+ransomware&pg=PA84.

- ↑ Paul Ducklin (February 17, 2016). "Locky ransomware: What you need to know". Naked Security. https://nakedsecurity.sophos.com/2016/02/17/locky-ransomware-what-you-need-to-know/.

- ↑ Kevin Beaumont (February 17, 2016). "Locky ransomware virus spreading via Word documents". https://medium.com/@networksecurity/locky-ransomware-virus-spreading-via-word-documents-51fcb75618d2#.p8fn6zfbl.

- ↑ Krishnan, Rakesh. "How Just Opening an MS Word Doc Can Hijack Every File On Your System". http://thehackernews.com/2016/02/locky-ransomware-decrypt.html. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Spring, Tom (23 June 2016). "Necurs Botnet is Back, Updated With Smarter Locky Variant". Kaspersky Lab ZAO. https://threatpost.com/necurs-botnet-is-back-updated-with-smarter-locky-variant/118883/. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ↑ "Locky Ransomware Information, Help Guide, and FAQ". BleepingComputer. https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/virus-removal/locky-ransomware-information-help. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ↑ "AFRAIDGATE RIG-V FROM 81.177.140.7 SENDS "OSIRIS" VARIANT LOCKY". Malware-Traffic. http://www.malware-traffic-analysis.net/2016/12/23/index.html. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Abrams, Lawrence. "Locky Ransomware switches to Egyptian Mythology with the Osiris Extension". BleepingComputer. https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/locky-ransomware-switches-to-egyptian-mythology-with-the-osiris-extension/. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ "Locky Ransomware Distributed Via DOCM Attachments in Latest Email Campaigns". FireEye. https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2016/08/locky_ransomwaredis.html. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ↑ "Locky Ransomware Now Embedded in Javascript". FireEye. https://blog.cyren.com/articles/2016-Q3_locky-ransomware-now-embedded-in-javascript.html. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ↑ "Locky ransomware". https://www.avast.com/c-locky. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ↑ "locky ransomware threats". http://www.idigitaltimes.com/new-locky-ransomware-virus-spreading-alarming-rate-can-malware-be-removed-and-files-512956. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ "Google Trends". https://www.google.com/trends/explore?date=2016-01-01%202016-09-28&q=locky.

- ↑ Richard Winton (February 18, 2016). "Hollywood hospital pays 17,000 bitcoin to hackers; FBI investigating". LA Times. http://www.latimes.com/business/technology/la-me-ln-hollywood-hospital-bitcoin-20160217-story.html.

- ↑ Jessica Davis (February 26, 2016). "Meet the most recent cybersecurity threat: Locky". Healthcare IT News. http://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/meet-most-recent-cybersecurity-threat-locky.

- ↑ Krishnan, Rakesh. "Ransomware attacks on Hospitals put Patients at Risk". http://thehackernews.com/2016/04/hospital-ransomware.html. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ↑ Loeb, Larry. "Necurs Botnet Comes Back From the Dead". https://securityintelligence.com/news/necurs-botnet-comes-back-from-the-dead/. Retrieved 27 June 2016.