Finance:Diminishing returns

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

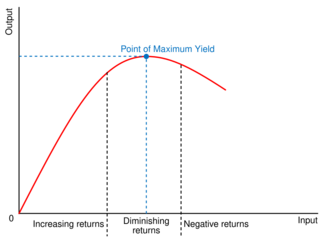

In economics, diminishing returns are the decrease in marginal (incremental) output of a production process as the amount of a single factor of production is incrementally increased, holding all other factors of production equal (ceteris paribus).[1] The law of diminishing returns (also known as the law of diminishing marginal productivity) states that in productive processes, increasing a factor of production by one unit, while holding all other production factors constant, will at some point return a lower unit of output per incremental unit of input.[2][3] The law of diminishing returns does not cause a decrease in overall production capabilities, rather it defines a point on a production curve whereby producing an additional unit of output will result in a loss and is known as negative returns. Under diminishing returns, output remains positive, but productivity and efficiency decrease.

The modern understanding of the law adds the dimension of holding other outputs equal, since a given process is understood to be able to produce co-products.[4] An example would be a factory increasing its saleable product, but also increasing its CO2 production, for the same input increase.[2] The law of diminishing returns is a fundamental principle of both micro and macro economics and it plays a central role in production theory.[5]

The concept of diminishing returns can be explained by considering other theories such as the concept of exponential growth.[6] It is commonly understood that growth will not continue to rise exponentially, rather it is subject to different forms of constraints such as limited availability of resources and capitalisation which can cause economic stagnation.[7] This example of production holds true to this common understanding as production is subject to the four factors of production which are land, labour, capital and enterprise.[8] These factors have the ability to influence economic growth and can eventually limit or inhibit continuous exponential growth.[9] Therefore, as a result of these constraints the production process will eventually reach a point of maximum yield on the production curve and this is where marginal output will stagnate and move towards zero.[10] Innovation in the form of technological advances or managerial progress can minimise or eliminate diminishing returns to restore productivity and efficiency and to generate profit.[11]

This idea can be understood outside of economics theory, for example, population. The population size on Earth is growing rapidly, but this will not continue forever (exponentially). Constraints such as resources will see the population growth stagnate at some point and begin to decline.[6] Similarly, it will begin to decline towards zero but not actually become a negative value, the same idea as in the diminishing rate of return inevitable to the production process.

History

The concept of diminishing returns can be traced back to the concerns of early economists such as Johann Heinrich von Thünen, Jacques Turgot, Adam Smith,[12] James Steuart, Thomas Robert Malthus, and [13] David Ricardo. The law of diminishing returns can be traced back to the 18th century, in the work of Jacques Turgot. He argued that "each increase [in an input] would be less and less productive."[14] In 1815, David Ricardo, Thomas Malthus, Edward West, and Robert Torrens applied the concept of diminishing returns to land rent. These works were relevant to the committees of Parliament in England, who were investigating why grain prices were so high, and how to reduce them. The four economists concluded that the prices of the products had risen due to the Napoleonic Wars, which affected international trade and caused farmers to move to lands which were undeveloped and further away. In addition, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, grain imports were restored which caused a decline in prices because the farmers needed to attract customers and sell their products faster.[15]

Classical economists such as Malthus and Ricardo attributed the successive diminishment of output to the decreasing quality of the inputs whereas Neoclassical economists assume that each "unit" of labor is identical. Diminishing returns are due to the disruption of the entire production process as additional units of labor are added to a fixed amount of capital. The law of diminishing returns remains an important consideration in areas of production such as farming and agriculture.

Proposed on the cusp of the First Industrial Revolution, it was motivated with single outputs in mind. In recent years, economists since the 1970s have sought to redefine the theory to make it more appropriate and relevant in modern economic societies.[4] Specifically, it looks at what assumptions can be made regarding number of inputs, quality, substitution and complementary products, and output co-production, quantity and quality.

The origin of the law of diminishing returns was developed primarily within the agricultural industry. In the early 19th century, David Ricardo as well as other English economists previously mentioned, adopted this law as the result of the lived experience in England after the war. It was developed by observing the relationship between prices of wheat and corn and the quality of the land which yielded the harvests.[16] The observation was that at a certain point, that the quality of the land kept increasing, but so did the cost of produce etc. Therefore, each additional unit of labour on agricultural fields, actually provided a diminishing or marginally decreasing return.[17]

Example

A common example of diminishing returns is choosing to hire more people on a factory floor to alter current manufacturing and production capabilities. Given that the capital on the floor (e.g. manufacturing machines, pre-existing technology, warehouses) is held constant, increasing from one employee to two employees is, theoretically, going to more than double production possibilities and this is called increasing returns.

If 50 people are employed, at some point, increasing the number of employees by two percent (from 50 to 51 employees) would increase output by two percent and this is called constant returns.

Further along the production curve at, for example 100 employees, floor space is likely getting crowded, there are too many people operating the machines and in the building, and workers are getting in each other's way. Increasing the number of employees by two percent (from 100 to 102 employees) would increase output by less than two percent and this is called "diminishing returns."

After achieving the point of maximum output, employing additional workers, this will give negative returns.[18]

Through each of these examples, the floor space and capital of the factor remained constant, i.e., these inputs were held constant. By only increasing the number of people, eventually the productivity and efficiency of the process moved from increasing returns to diminishing returns.

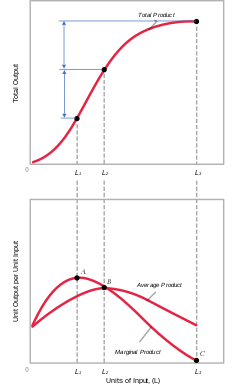

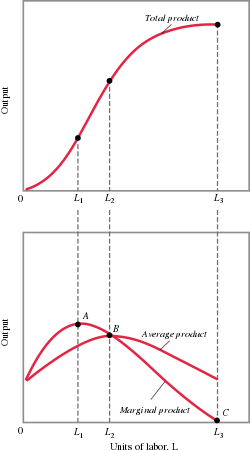

To understand this concept thoroughly, acknowledge the importance of marginal output or marginal returns. Returns eventually diminish because economists measure productivity with regard to additional units (marginal). Additional inputs significantly impact efficiency or returns more in the initial stages.[19] The point in the process before returns begin to diminish is considered the optimal level. Being able to recognize this point is beneficial, as other variables in the production function can be altered rather than continually increasing labor.

Further, examine something such as the Human Development Index, which would presumably continue to rise so long as GDP per capita (in Purchasing Power Parity terms) was increasing. This would be a rational assumption because GDP per capita is a function of HDI. Even GDP per capita will reach a point where it has a diminishing rate of return on HDI.[20] Just think, in a low income family, an average increase of income will likely make a huge impact on the wellbeing of the family. Parents could provide abundantly more food and healthcare essentials for their family. That is a significantly increasing rate of return. But, if you gave the same increase to a wealthy family, the impact it would have on their life would be minor. Therefore, the rate of return provided by that average increase in income is diminishing.

Mathematics

Signify [math]\displaystyle{ Output = O \ ,\ Input = I \ ,\ O = f(I) }[/math]

Increasing Returns: [math]\displaystyle{ 2\cdot f(I)\lt f(2\cdot I) }[/math]

Constant Returns: [math]\displaystyle{ 2\cdot f(I)=f(2\cdot I) }[/math]

Diminishing Returns: [math]\displaystyle{ 2\cdot f(I)\gt f(2\cdot I) }[/math]

Production function

There is a widely recognised production function in economics: Q= f(NR, L, K, t, E):

- The point of diminishing returns can be realised, by use of the second derivative in the above production function.

- Which can be simplified to: Q= f(L,K).

- This signifies that output (Q) is dependent on a function of all variable (L) and fixed (K) inputs in the production process. This is the basis to understand. What is important to understand after this is the math behind Marginal Product. MP= ΔTP/ ΔL. [21]

- This formula is important to relate back to diminishing rates of return. It finds the change in total product divided by change in labour.

- The Marginal Product formula suggests that MP should increase in the short run with increased labour. In the long run, this increase in workers will either have no effect or a negative effect on the output. This is due to the effect of fixed costs as a function of output, in the long run.[22]

Link with Output Elasticity

Start from the equation for the Marginal Product: [math]\displaystyle{ {\Delta Out \over \Delta In_1}= {{f(In_2, In_1 +\Delta In_1)-f(In_1,In_2)} \over \Delta In_1} }[/math]

To demonstrate diminishing returns, two conditions are satisfied; marginal product is positive, and marginal product is decreasing.

Elasticity, a function of Input and Output, [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon ={In\over Out}\cdot{\delta Out\over \delta In} }[/math], can be taken for small input changes. If the above two conditions are satisfied, then [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \epsilon \lt 1 }[/math].[23]

This works intuitively;

- If [math]\displaystyle{ {In\over Out} }[/math] is positive, since negative inputs and outputs are impossible,

- And [math]\displaystyle{ {\delta Out\over \delta In} }[/math] is positive, since a positive return for inputs is required for diminishing returns

- Then [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \epsilon }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ {\delta Out \over Out} }[/math] is relative change in output, [math]\displaystyle{ {\delta In \over In} }[/math] is relative change in input

- The relative change in output is smaller than the relative change in input; ~input requires increasing effort to change output~

- Then [math]\displaystyle{ {\delta Out \over Out}/{\delta In \over In}={In\over Out}\cdot{\delta Out\over \delta In}=\epsilon \lt 1 }[/math]

Returns and costs

There is an inverse relationship between returns of inputs and the cost of production,[24] although other features such as input market conditions can also affect production costs. Suppose that a kilogram of seed costs one dollar, and this price does not change. Assume for simplicity that there are no fixed costs. One kilogram of seeds yields one ton of crop, so the first ton of the crop costs one dollar to produce. That is, for the first ton of output, the marginal cost as well as the average cost of the output is per ton. If there are no other changes, then if the second kilogram of seeds applied to land produces only half the output of the first (showing diminishing returns), the marginal cost would equal per half ton of output, or per ton, and the average cost is per 3/2 tons of output, or /3 per ton of output. Similarly, if the third kilogram of seeds yields only a quarter ton, then the marginal cost equals per quarter ton or per ton, and the average cost is per 7/4 tons, or /7 per ton of output. Thus, diminishing marginal returns imply increasing marginal costs and increasing average costs.

Cost is measured in terms of opportunity cost. In this case the law also applies to societies – the opportunity cost of producing a single unit of a good generally increases as a society attempts to produce more of that good. This explains the bowed-out shape of the production possibilities frontier.

Justification

Ceteris paribus

Part of the reason one input is altered ceteris paribus, is the idea of disposability of inputs.[25] With this assumption, essentially that some inputs are above the efficient level. Meaning, they can decrease without perceivable impact on output, after the manner of excessive fertiliser on a field.

If input disposability is assumed, then increasing the principal input, while decreasing those excess inputs, could result in the same "diminished return", as if the principal input was changed certeris paribus. While considered "hard" inputs, like labour and assets, diminishing returns would hold true. In the modern accounting era where inputs can be traced back to movements of financial capital, the same case may reflect constant, or increasing returns.

It is necessary to be clear of the "fine structure"[4] of the inputs before proceeding. In this, ceteris paribus is disambiguating.

See also

- Diminishing marginal utility

- Diseconomies of scale

- Economies of scale

- Gold plating (project management)

- Learning curve

- Experience curve effects

- Liebig's Law of the minimum

- Marginal value theorem

- Opportunity cost

- Returns to scale

- Pareto efficiency

- Self-organized criticality

- Submodular set function

- Sunk-cost fallacy

- Tendency of the rate of profit to fall

- Analysis paralysis

- Teamwork

- Amdahl's law

References

Citations

- ↑ "Diminishing Returns". 2017-12-27. https://www.britannica.com/topic/microeconomics.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Samuelson, Paul A.; Nordhaus, William D. (2001). Microeconomics (17th ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 110. ISBN 0071180664.

- ↑ Erickson, K.H. (2014-09-06). Economics: A Simple Introduction. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 44. ISBN 978-1501077173.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Shephard, Ronald W.; Färe, Rolf (1974-03-01). "The law of diminishing returns" (in en). Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie 34 (1): 69–90. doi:10.1007/BF01289147. ISSN 1617-7134. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01289147.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. 26 Jan 2013. ISBN 9781593392925. https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/163723/diminishing-returns.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Exponential growth & logistic growth (article)" (in en). https://www.khanacademy.org/science/ap-biology/ecology-ap/population-ecology-ap/a/exponential-logistic-growth.

- ↑ "What Is Stagflation, What Causes It, and Why Is It Bad?" (in en). https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/stagflation.asp.

- ↑ "What are the Factors of Production" (in en). https://www.stlouisfed.org/education/economic-lowdown-podcast-series/episode-2-factors-of-production.

- ↑ "What is Production? | Microeconomics". https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-microeconomics/chapter/what-is-production/.

- ↑ Pichère, Pierre (2015-09-02). The Law of Diminishing Returns: Understand the fundamentals of economic productivity. 50Minutes.com. p. 17. ISBN 978-2806270092.

- ↑ "Knowledge, Technology and Complexity in Economic Growth" (in en). https://rcc.harvard.edu/knowledge-technology-and-complexity-economic-growth.

- ↑ Smith, Adam. The wealth of nations. Thrifty books. ISBN 9780786514854.

- ↑ Pichère, Pierre (2015-09-02). The Law of Diminishing Returns: Understand the fundamentals of economic productivity. 50Minutes.com. pp. 9–12. ISBN 978-2806270092.

- ↑ Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot (1727–1781), Library of Economics and Liberty (2nd ed.), Liberty Fund, 2008, http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Turgot.html, retrieved 16 July 2013

- ↑ Brue, Stanley L (1993-08-01). "Retrospectives: The Law of Diminishing Returns" (in en). Journal of Economic Perspectives 7 (3): 185–192. doi:10.1257/jep.7.3.185. ISSN 0895-3309.

- ↑ Cannan, Edwin (March 1892). "The Origin of the Law of Diminishing Returns, 1813-15". The Economic Journal 2 (5): 53–69. doi:10.2307/2955940. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2955940.

- ↑ "Law of Diminishing Marginal Returns: Definition, Example, Use in Economics" (in en). https://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/lawofdiminishingmarginalreturn.asp.

- ↑ "The Law of Diminishing Returns - Personal Excellence" (in en-US). 2016-04-12. https://personalexcellence.co/blog/diminishing-returns/.

- ↑ "Law of Diminishing Returns & Point of Diminishing Returns Definition" (in en-US). https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/economics/point-of-diminishing-returns/.

- ↑ Cahill, Miles B. (October 2002). "Diminishing returns to GDP and the Human Development Index" (in en). Applied Economics Letters 9 (13): 885–887. doi:10.1080/13504850210158999. ISSN 1350-4851. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13504850210158999.

- ↑ Carter, H. O.; Hartley, H. O. (April 1958). "A Variance Formula for Marginal Productivity Estimates using the Cobb-Douglas Function". Econometrica 26 (2): 306. doi:10.2307/1907592. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1907592.

- ↑ "The Production Function | Microeconomics". https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-microeconomics/chapter/the-production-function/.

- ↑ Robinson, R. Clark (July 2006). "Math 285-2 - Handouts for Math 285-2 - Marginal Product of Labor and Capital". https://sites.math.northwestern.edu/~clark/285/2006-07/handouts/marginal.pdf.

- ↑ "Why It Matters: Production and Costs | Microeconomics". https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wmopen-microeconomics/chapter/why-it-matters-production/.

- ↑ Shephard, Ronald W. (1970-03-01). "Proof of the law of diminishing returns" (in en). Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie 30 (1): 7–34. doi:10.1007/BF01289990. ISSN 1617-7134. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01289990.

Sources

- Case, Karl E.; Fair, Ray C. (1999). Principles of Economics (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-961905-4.

|