Finance:Preference (economics)

In economics, and in other social sciences, preference refers to an order by which an agent, while in search of an "optimal choice", ranks alternatives based on their respective utility. Preferences are evaluations that concern matters of value, in relation to practical reasoning.[1] Individual preferences are determined by taste, need, ..., as opposed to price, availability or personal income. Classical economics assumes that people act in their best (rational) interest.[2] In this context, rationality would dictate that, when given a choice, an individual will select an option that maximizes their self-interest. But preferences are not always transitive, both because real humans are far from always being rational and because in some situations preferences can form cycles, in which case there exists no well-defined optimal choice. An example of this is Efron dice.

The concept of preference plays a key role in many disciplines, including moral philosophy and decision theory. The logical properties that preferences possess also have major effects on rational choice theory, which in turn affects all modern economic topics.[3]

Using the scientific method, social scientists aim to model how people make practical decisions in order to explain the causal underpinnings of human behaviour or to predict future behaviours. Although economists are not typically interested in the specific causes of a person's preferences, they are interested in the theory of choice because it gives a background to empirical demand analysis.[4]

Stability of preference is a deep assumption behind most economic models. Gary Becker drew attention to this with his remark that "the combined assumptions of maximizing behavior, market equilibrium, and stable preferences, used relentlessly and unflinchingly, form the heart of the economic approach as it is."[5] More complex conditions of adaptive preference were explored by Carl Christian von Weizsäcker in his paper "The Welfare Economics of Adaptive Preferences" (2005), while remarking that.[6] Traditional neoclassical economics has worked with the assumption that the preferences of agents in the economy are fixed. This assumption has always been disputed outside neoclassical economics.

History

In 1926, Ragnar Frisch was the first to develop a mathematical model of preferences in the context of economic demand and utility functions.[7] Up to then, economists had used an elaborate theory of demand that omitted primitive characteristics of people. This omission ceased when, at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, logical positivism predicated the need to relate theoretical concepts to observables.[8] Whereas economists in the 18th and 19th centuries felt comfortable theorizing about utility, with the advent of logical positivism in the 20th century, they felt they needed a more empirical structure. Because binary choices are directly observable, they instantly appeal to economists. The search for observables in microeconomics is taken even further by the revealed preference theory, which holds consumers' preferences can be revealed by what they purchase under different circumstances, particularly under different income and price circumstances.[9]

Despite utilitarianism and decision theory, many economists have differing definitions of what a rational agent is. In the 18th century, utilitarianism gave insight into the utility-maximizing versions of rationality; however, economists still have no consistent definition or understanding of what preferences and rational actors should be analyzed.[10]

Since the pioneer efforts of Frisch in the 1920s, the representability of a preference structure with a real-valued function is one of the major issues pervading the theory of preferences. This has been achieved by mapping it to the mathematical index called utility. Von Neumann and Morgenstern's 1944 book "Games and Economic Behavior" treated preferences as a formal relation whose properties can be stated axiomatically. These types of axiomatic handling of preferences soon began to influence other economists: Marschak adopted it by 1950, Houthakker employed it in a 1950 paper, and Kenneth Arrow perfected it in his 1951 book "Social Choice and Individual Values".[11]

Gérard Debreu, influenced by the ideas of the Bourbaki group, championed the axiomatization of consumer theory in the 1950s, and the tools he borrowed from the mathematical field of binary relations have become mainstream since then. Even though the economics of choice can be examined either at the level of utility functions or at the level of preferences, moving from one to the other can be useful. For example, shifting the conceptual basis from an abstract preference relation to an abstract utility scale results in a new mathematical framework, allowing new conditions on the preference structure to be formulated and investigated.

Another historical turning point can be traced back to 1895, when Georg Cantor proved in a theorem that if a binary relation is linearly ordered, then it is also isomorphic in the ordered real numbers. This notion would become very influential for the theory of preferences in economics: by the 1940s, prominent authors such as Paul Samuelson would theorize about people having weakly ordered preferences.[12]

Historically, preference in economics as a form of utility can be categorized as ordinal or cardinal data. Both introduced in the 20th century, cardinal and ordinal utility take opposing theories and mindsets in applying and analyzing preference in utility. Vilfredo Pareto introduced the concept of ordinal utility, while Carl Menger led the idea of cardinal utility. Ordinal utility, in summation, is the direct following of preference, where an optimal choice is taken over a set of parameters. A person is expected to act in their best interests and dedicate their preference to the outcome with the greatest utility. Ordinal utility assumes that an individual will not have the same utility from a preference as any other individual because they likely will not experience the same parameters which cause them to decide a given outcome. Cardinal utility is a function of utility where a person makes a decision based on a preference, and the preference decision is weighted based on a quantitative value of utility. This utility unit is assumed to be universally applicable and constant across all individuals. Cardinal utility also assumes consistency across individuals' decision-making processes, assuming all individuals will have the same preference, with all variables held constant. Marshall found that "a good deal of the analysis of consumer behavior could be greatly simplified by assuming that the marginal utility of income is constant" (Robert H. Strotz.[13]), however, this cannot be held to the utility of resources and decision-making applied to income. Ordinal and cardinal utility theories provide unique viewpoints on utility, can be used differently to model decision-making preferences and utilization development, and can be used across many applications for economic analysis.

Notation

There are two fundamental comparative value concepts, namely strict preference (better) and indifference (equal in value to).[14] These two concepts are expressed in terms of an agent's best wishes; however, they also express objective or intersubjective valid superiority that does not coincide with the pattern of wishes of any person.

Suppose the set of all states of the world is [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] and an agent has a preference relation on [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]. It is common to mark the weak preference relation by [math]\displaystyle{ \preceq }[/math], so that [math]\displaystyle{ x \preceq y }[/math] means "the agent wants y at least as much as x" or "the agent weakly prefers y to x".

The symbol [math]\displaystyle{ \sim }[/math] is used as a shorthand to denote an indifference relation: [math]\displaystyle{ x\sim y \iff (x\preceq y \land y\preceq x) }[/math], which reads "the agent is indifferent between y and x", meaning the agent receives the same level of benefit from each.

The symbol [math]\displaystyle{ \prec }[/math] is used as a shorthand to the strong preference relation: [math]\displaystyle{ x\prec y \iff (x\preceq y \land y\not\preceq x) }[/math]), it is redundant inasmuch as the completeness axiom implies it already.[15]

Non-satiation of preferences

Non-satiation refers to the belief any commodity bundle with at least as much of one good and more of the other must provide a higher utility, showing that more is always regarded as "better". This assumption is believed to hold as when consumers are able to discard excess goods at no cost, then consumers can be no worse off with extra goods.[16] This assumption does not preclude diminishing marginal utility.

Example

Option A

- Apple = 5

- Orange = 3

- Banana = 2

Option B

- Apple = 6

- Orange = 4

- Banana = 2

In this situation, utility from Option B > A, as it contains more apples and oranges with bananas being constant.

Transitivity

Transitivity of preferences is a fundamental principle shared by most major contemporary rational, prescriptive, and descriptive models of decision-making.[17] In order to have transitive preferences, a person, player, or agent that prefers choice option A to B and B to C must prefer A to C. The most discussed logical property of preferences are the following:

- A≽B ∧ B≽C → A≽C (transitivity of weak preference)

- A∼B ∧ B∼C → A∼C (transitivity of indifference)

- A≻B ∧ B≻C → A≻C (transitivity of strict preference)

Some authors go so far as to assert that a claim of a decision maker’s violating transitivity requires evidence beyond any reasonable doubt.[17] But there are scenarios involving a finite set of alternatives where, for any alternative there exists another that a rational agent would prefer. One class of such scenarios involves intransitive dice. And Schumm gives examples of non-transitivity based on Just-noticeable differences.[18]

Most commonly used axioms

- Order-theoretic: acyclicity, the semi-order property, completeness

- Topological: continuity, openness, or closeness of the preference sets

- Linear-space: convexity, homogeneity

Normative interpretations of the axioms

Everyday experience suggests that people at least talk about their preferences as if they had personal "standards of judgment" capable of being applied to the particular domain of alternatives that present themselves from time to time.[19] Thus, the axioms attempt to model the decision maker's preferences, not over the actual choice, but over the type of desirable procedure (a procedure that any human being would like to follow). Behavioral economics investigates human behaviour which violates the above axioms. Believing in axioms in a normative way does not imply that everyone must behave according to them.[8]

Consumers whose preference structures violate transitivity would get exposed to being exploited by some unscrupulous person. For instance, Maria prefers apples to oranges, oranges to bananas, and bananas to apples. Let her be endowed with an apple, which she can trade in a market. Because she prefers bananas to apples, she is willing to pay one cent to trade her apple for a banana. Afterwards, Maria is willing to pay another cent to trade her banana for an orange, the orange for an apple, and so on. There are other examples of this kind of irrational behaviour.

Completeness implies that some choice will be made, an assertion that is more philosophically questionable. In most applications, the set of consumption alternatives is infinite, and the consumer is unaware of all preferences. For example, one does not have to choose between going on holiday by plane or train. Suppose one does not have enough money to go on holiday anyway. In that case, it is unnecessary to attach a preference order to those alternatives (although it can be nice to dream about what one would do if one won the lottery). However, preference can be interpreted as a hypothetical choice that could be made rather than a conscious state of mind. In this case, completeness amounts to an assumption that the consumers can always make up their minds whether they are indifferent or prefer one option when presented with any pair of options.

Under some extreme circumstances, there is no "rational" choice available. For instance, if asked to choose which one of one's children will be killed, as in Sophie's Choice, there is no rational way out of it. In that case, preferences would be incomplete since "not being able to choose" is not the same as "being indifferent".

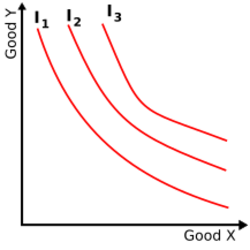

The indifference relation ~ is an equivalence relation. Thus, we have a quotient set S/~ of equivalence classes of S, which forms a partition of S. Each equivalence class is a set of packages that are equally preferred. If there are only two commodities, the equivalence classes can be graphically represented as indifference curves. Based on the preference relation on S, we have a preference relation on S/~. As opposed to the former, the latter is antisymmetric and a total order.

Factors which affect consumer preferences

Indifference curve

An indifference curve[20] is a graphical representation that shows the combinations of quantities of two goods for which an individual will have equal preference or utility. It is named as such because the consumer would be indifferent between choosing any combination or bundle of commodities.[21] An indifference curve can be detected in a market when the economics of scope is not overly diverse, or the goods and services are part of a perfect market. Any bundles on the same indifference curve have the same utility level. One example of this is deodorant. Deodorant is similarly priced throughout several different brands. Deodorant also has no major differences in use; therefore, consumers have no preference in what they should use. Indifference curves are negatively sloped because of the non-satiation of preferences, as consumers cannot be indifferent between two bundles if one has more of both goods. The indifference curves are also curved inwards due to diminishing marginal utility, i.e., the reduction in the utility of every additional unit as consumers consume more of the same good. The slope of the indifference curve measures the marginal rate of substitution, which can be defined as the number of units of one good needed to replace one unit of another good without changing the overall utility.[22]

Changes in new technology

New changes in technology are a big factor in changes of consumer preferences. When an industry has a new competitor who has found ways to make the goods or services work more effectively, it can change the market completely. An example of this is the Android operating system. Some years ago, Android struggled to compete with Apple for market share. With the advances in technology throughout the last five years, they have passed the stagnant Apple brand. Changes in technology examples are but are not limited to increased efficiency, longer-lasting batteries, and a new easier interface for consumers.

Social influence

Changes in preference can also develop as a result of social interactions among consumers. If decision-makers are asked to make choices in isolation, the results may differ from those if they were to make choices in a group setting. By means of social interactions, individual preferences can evolve without any necessary change to the utility.[23] This can be exemplified by taking the example of a group of friends having lunch together. Individuals in such a group may change their food preferences after being exposed to their friends' preferences. Similarly, if an individual tends to be risk-averse but is exposed to a group of risk-seeking people, his preferences may change over time.

Types of preferences

Convex preferences

Convex preferences relate to averages between two points on an indifference curve. It comes in two forms, weak and strong. In its weak form, convex preferences state that if [math]\displaystyle{ A \sim B }[/math]. Then the average of A and B is at least as good as A. In contrast, the average of A and B would be preferred in its strong form. This is why in its strong form, the indifference line curves in, meaning that the average of any two points would result in a point further away from the origin, thus giving a higher utility.[24] One way to check convexity is to connect two random points on the same indifference curve and draw a straight line through these two points, and then pick one point on the straight line between those two points. If the utility level of the picked point on the straight line is greater than that of those two points, this is a strictly convex preference. Convexity is one of the prerequisites for a rational consumer in the market when maximizing his utility level under the budget constraint.

Concave preferences

Concave preferences are the opposite of convex, where when [math]\displaystyle{ A \sim B }[/math], the average of A and B is worse than A. This is because concave curves slope outwards, meaning an average between two points on the same indifference curve would result in a point closer to the origin, thus giving a lower utility.[25] To determine whether the preference is concave or not, one way is still to connect two random points on the same difference curve and draw a straight line through these two points, and then pick one point on the straight line between those two points. If the utility level of the picked point on the straight line is lower than that of those two points, this is a strictly concave preference.

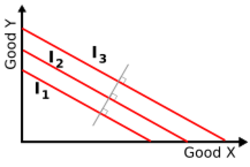

Straight line indifference

Straight-line similarities occur when there are perfect substitutes. Perfect substitutes are goods and/or services that can be used the same way as the good or service it replaces. When [math]\displaystyle{ A \sim B }[/math], the average of A and B will fall on the same indifference line and give the same utility.[26]

Types of goods affecting preferences

When a consumer is faced with a choice between different goods, the type of goods they are choosing between will affect how they make their decision process. To begin with, when there are normal goods, these goods have a direct correlation with the income the consumer makes, meaning as they make more money, they will choose to consume more of this good, and as their income decreases, they will consume less of the good. However, the opposite is inferior goods; these negatively correlate with income. Hence, as consumers make less money, they'll consume more inferior goods as they are seen as less desirable, meaning they come with a reduced cost. As they make more money, they'll consume fewer inferior goods and have the money available to buy more desirable goods.[27] An example of a normal good would-be branded clothes, as they are more expensive compared to their inferior good counterparts which are non-branded clothes. Goods that are not affected by income as referred to as a necessity good, which are product(s) and services that consumers will buy regardless of the changes in their income levels. These usually include medical care, clothing and basic food. Finally, there are also luxury goods, which are the most expensive and deemed the most desirable. Just like normal goods, as income increases, so is the demand for luxury goods; however, in the case of luxury goods, the greater the income, the greater the demand for luxury goods.[28]

Applications to theories of utility

In economics, a utility function is often used to represent a preference structure such that [math]\displaystyle{ u\left(A\right)\geqslant u\left(B\right) }[/math] if and only if [math]\displaystyle{ A \succsim B }[/math]. The idea is to associate each class of indifference with a real number such that if one class is preferred to the other, then the number of the first one is greater than that of the second one. When a preference order is both transitive and complete, it is standard practice to call it a rational preference relation, and the people who comply with it are rational agents. A transitive and complete relation is called a weak order (or total preorder) . The literature on preferences is far from being standardized regarding terms such as complete, partial, strong, and weak. Together with the terms "total", "linear", "strong complete", "quasi-orders", "pre-orders", and "sub-orders", which also have different meanings depending on the author's taste, there has been an abuse of semantics in the literature.[19]

According to Simon Board, a continuous utility function always exists if [math]\displaystyle{ \succsim }[/math] is a continuous rational preference relation on [math]\displaystyle{ R^n }[/math].[29] For any such preference relation, there are many continuous utility functions that represent it. Conversely, every utility function can be used to construct a unique preference relation.

All the above is independent of the prices of the goods and services and the budget constraints consumers face. These determine the feasible bundles (which they can afford). According to the standard theory, consumers choose a bundle within their budget such that no other feasible bundle is preferred over it, thus maximizing their utility.

Primitive equivalents of some known properties of utility functions

- An increasing utility function is associated with a monotonic preference relation.

- Quasi-concave utility functions are associated with a convex preference order. When non-convex preferences arise, the Shapley–Folkman lemma is applicable.

Lexicographic preferences

Lexicographic preferences are a special case of preferences that assign an infinite value to a good when compared with the other goods of a bundle.[30]

Georgescu-Roegen pointed out that the measurability of the utility theory is limited as it excludes lexicographic preferences. Causing an amplified level of awareness placed upon lexicographic preferences as a substitute hypothesis on consumer behaviour.[31]

Strict versus weak

The possibility of defining a strict preference relation [math]\displaystyle{ \succ }[/math] as distinguished from the weaker one [math]\displaystyle{ \succsim }[/math], and vice versa, suggests in principle an alternative approach of starting with the strict relation [math]\displaystyle{ \succ }[/math] as the primitive concept and deriving the weaker one and the indifference relation. However, an indifference relation derived this way will generally not be transitive.[7] The conditions to avoid such inconsistencies were studied in detail by Andranik Tangian.[30] According to Kreps "beginning with strict preference makes it easier to discuss non-comparability possibilities".[32]

Elicitation of preferences

The mathematical foundations of most common types of preferences — that are representable by quadratic or additive utility functions — laid down by Gérard Debreu[33][34] enabled Andranik Tangian to develop methods for their elicitation. In particular, additive and quadratic preference functions in [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] variables can be constructed from interviews, where questions are aimed at tracing totally [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] 2D-indifference curves in [math]\displaystyle{ n - 1 }[/math] coordinate planes.[35][36]

Criticism

Some critics say that rational theories of choice and preference theories rely too heavily on the assumption of invariance, which states that the relation of preference should not depend on the description of the options or on the method of elicitation. But without this assumption, one's preferences cannot be represented as maximization of utility.[37]

Milton Friedman said that segregating taste factors from objective factors (i.e. prices, income, availability of goods) is conflicting because both are "inextricably interwoven".

The non-satiation of preferences is another topic that generates debate since it essentially states that "more is better than less." Many argue that this interpretation is flawed and highly subjective. Many critics call for a specification of preference to be able to interpret the non-satiation principle reasonably.[38] For example, in cases where there is a choice between more pollution and less pollution, consumers would rationally prefer less pollution thus making the non-satiation principle fail. Similar conflicts with the principle can be seen in choices that involve bulky goods in a limited space, such as an excess of furniture in a small house.

The concept of transitivity is highly debated, with many examples suggesting that it does not generally hold. One of the most well-known is the Sorites paradox, which shows that indifference between small changes in value can be incrementally extended to indifference between large changes in values.[39]

Another criticism comes from philosophy. Philosophers cast doubt that when most consumers share the same preference in the same market, which may lead to the result that the shared preference has become somewhat objective, whether the judgments of preferences for each individual will still depend on subjectivity or not.[clarification needed]

See also

References

- ↑ Broome, John (1993). "Can a Humean Be Moderate?". in Frey, R. G.; Morris, Christopher. Value, Welfare and Morality. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Blume, Lawrence (15 December 2016). Durlauf, Steven N; Blume, Lawrence E. eds. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-58802-2. ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5.

- ↑ Hansson, Sven Ove; Grüne-Yanoff, Till (May 4, 2018). "Preferences". Stanford Encyclopedia of Economics. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/preferences/.

- ↑ Arrow, Kenneth (1958). "Utilities, attitudes, choices: a review note". Econometrica 26 (1): 1–23. doi:10.2307/1907381.

- ↑ Becker, Gary (1976). The Economic Approach to Human Behavior. University of Chicago Press. p. 5. ISBN 0226041123. https://www.pauldeng.com/pdf/Becker_the%20economic%20approach%20to%20human%20behavior.pdf. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ↑ Template:Cite SSRN

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Barten, Anton and Volker Böhm. (1982). "Consumer theory", in Kenneth Arrow and Michael Intrilligator (eds.) Handbook of mathematical economics. Vol. II, p. 384

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gilboa, Itzhak. (2009). Theory of Decision under uncertainty . Cambridge: Cambridge university press

- ↑ Roper, James and Zin, David. (2008). "A Note on the Pure Theory of Consumer's Behaviour"

- ↑ Blume, Lawrence E.; Easley, David (2008). "Rationality". The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. pp. 1–13. doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2138-1. ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5.

- ↑ Moscati, Ivan (2004). "Early Experiments in Consumer Demand Theory". http://128.118.178.162/eps/mhet/papers/0506/0506003.pdf.

- ↑ Fishburn, Peter (1994). "Utility and subjective probability", in Robert Aumann and Sergiu Hart (eds). Handbook of game theory. Vol. 2. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. pp. 1397–1435.

- ↑ Robert H. Strotz

- ↑ Halldén, Sören (1957). "On the Logic of Betterm Lund: Library of Theoria" (10).

- ↑ Mas-Colell, Andreu, Michael Whinston and Jerry Green (1995). Microeconomic theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press ISBN:0-19-507340-1

- ↑ Bertoletti, Paolo; Etro, Federico (2016). "Preferences, entry, and market structure". RAND Journal of Economics 47 (4): 792–821. doi:10.1111/1756-2171.12155.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Clintin P. Davis-Stober; Michel Regenwetter; Jason Dana (2011). "Transitivity of Preferences". Psychological Review 118 (1): 42–56. doi:10.1037/a0021150. PMID 21244185. https://www.chapman.edu/research/institutes-and-centers/economic-science-institute/_files/ifree-papers-and-photos/michel-regenwetter1.pdf. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ↑ George F. Schumm (Nov 1987). "Transitivity, Preference and Indifference". Philosophical Studies 52 (3): 435–437.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Shapley, Lloyd and Martin Shubik. (1974). "Game theory in economics". RAND Report R-904/4

- ↑ "Indifference curve" (in en), Wikipedia, 2023-02-03, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Indifference_curve&oldid=1137303165, retrieved 2023-06-04

- ↑ University of Southern Indiana. (2021). Retrieved 26 April 2021, from https://www.usi.edu/business/cashel/331/CONSUMER.pdf

- ↑ Clower, Robert W. (1988). Intermediate microeconomics. Philip E. Graves, Robert L. Sexton. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-541496-8. OCLC 18350632. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/18350632.

- ↑ Fershtman, Chaim; Segal, Uzi (2018). "Preferences and Social Influence". American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 10 (3): 124–142. doi:10.1257/mic.20160190. ISSN 1945-7669. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26528494.

- ↑ Richter, Michael; Rubinst, Ariel (December 2019). "Convex preferences: A new definition". Theoretical Economics 14 (4): 1169–1183. doi:10.3982/TE3286.

- ↑ Lahiri, Somdeb (September 2015). "Concave Preferences Over Bundles and the First Fundamental Theorem of Welfare Economics". Social Science Research Network.

- ↑ Lipatov, Vilen (2021). "Preempting the Entry of Near Perfect Substitute". Journal of Competition Law & Economics 17: 194–210. doi:10.1093/joclec/nhaa023.

- ↑ Cherchye, Laurens (August 2020). "Revealed Preference Analysis with Normal Goods". American Economic Journal 12 (3): 165–188. doi:10.1257/mic.20180133. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles/pdf/doi/10.1257/mic.20180133.

- ↑ Mortelmans, D. (2005). Sign values in processes of distinction: The concept of luxury. 157. pp. 497–520.

- ↑ Board, Simon. "Preferences and Utility". UCLA. http://www.econ.ucla.edu/sboard/teaching/econ11_09/econ11_09_lecture2.pdf.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Tanguiane (Tangian), Andranick (1991). "2. Preferences and goal functions". Aggregation and representation of preferences: introduction to the mathematical theory of democracy. Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 23–50. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-76516-2. ISBN 978-3-642-76516-2.

- ↑ Hayakawa, Hiroaki (1978). "Lexicographic preferences and consumer theory". Journal of Behavioral Economics 7 (1): 17–51. doi:10.1016/0090-5720(78)90013-X.

- ↑ Kreps, David. (1990). A Course in Microeconomic Theory. New Jersey: Princeton University Press

- ↑ Debreu, Gérard (1952). "Definite and semidefinite quadratic forms". Econometrica 20 (2): 295–300. doi:10.2307/1907852.

- ↑ Debreu, Gérard (1960). "Topological methods in cardinal utility theory". in Arrow, Kenneth. Mathematical Methods in the Social Sciences,1959. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 16–26. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(03)00413-2.

- ↑ Tangian, Andranik (2002). "Constructing a quasi-concave quadratic objective function from interviewing a decision maker". European Journal of Operational Research 141 (3): 608–640. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(01)00185-0.

- ↑ Tangian, Andranik (2004). "A model for ordinally constructing additive objective functions". European Journal of Operational Research 159 (2): 476–512. doi:10.1016/S0377-2217(03)00413-2.

- ↑ Slovic, P. (1995). "The Construction of Preference". American Psychologist, Vol. 50, No. 5, pp. 364–371.

- ↑ Higgins, Richard S. (July 1972). "Satiation in Consumer Preference and the Demand Law". Southern Economic Journal 39 (1): 116–118. doi:10.2307/1056231. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1056231.

- ↑ Luce, Duncan. "Semiorders and a Theory of Utility Discrimination". Econometrica. https://www.imbs.uci.edu/files/personnel/luce/pre1990/1956/Luce_Econometrica_1956.pdf.

|