Finance:Markup rule

A markup rule is the pricing practice of a producer with market power, where a firm charges a fixed mark-up over its marginal cost.[1][page needed][2][page needed]

Derivation of the markup rule

Mathematically, the markup rule can be derived for a firm with price-setting power by maximizing the following expression for profit:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \pi = P(Q)\cdot Q - C(Q) }[/math]

- where

- Q = quantity sold,

- P(Q) = inverse demand function, and thereby the price at which Q can be sold given the existing demand

- C(Q) = total cost of producing Q.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] = economic profit

Profit maximization means that the derivative of [math]\displaystyle{ \pi }[/math] with respect to Q is set equal to 0:

- [math]\displaystyle{ P'(Q)\cdot Q+P-C'(Q)=0 }[/math]

- where

- P'(Q) = the derivative of the inverse demand function.

- C'(Q) = marginal cost–the derivative of total cost with respect to output.

This yields:

- [math]\displaystyle{ P'(Q)\cdot Q + P = C'(Q) }[/math]

or "marginal revenue" = "marginal cost".

- [math]\displaystyle{ P\cdot(P'(Q)\cdot Q/P+1)=MC }[/math]

By definition [math]\displaystyle{ P'(Q)\cdot Q/P }[/math] is the reciprocal of the price elasticity of demand (or [math]\displaystyle{ 1/ \epsilon }[/math]). Hence

- [math]\displaystyle{ P\cdot(1+1/{\epsilon})=P\cdot\left(\frac{1+\epsilon}{\epsilon}\right)=MC }[/math]

Letting [math]\displaystyle{ \eta }[/math] be the reciprocal of the price elasticity of demand,

- [math]\displaystyle{ P=\left(\frac{1}{1+\eta}\right)\cdot MC }[/math]

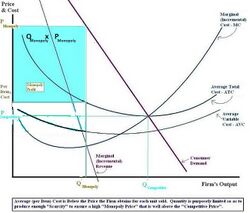

Thus a firm with market power chooses the output quantity at which the corresponding price satisfies this rule. Since for a price-setting firm [math]\displaystyle{ \eta\lt 0 }[/math] this means that a firm with market power will charge a price above marginal cost and thus earn a monopoly rent. On the other hand, a competitive firm by definition faces a perfectly elastic demand; hence it has [math]\displaystyle{ \eta=0 }[/math] which means that it sets the quantity such that marginal cost equals the price.

The rule also implies that, absent menu costs, a firm with market power will never choose a point on the inelastic portion of its demand curve (where [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon \ge -1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \eta \le -1 }[/math]). Intuitively, this is because starting from such a point, a reduction in quantity and the associated increase in price along the demand curve would yield both an increase in revenues (because demand is inelastic at the starting point) and a decrease in costs (because output has decreased); thus the original point was not profit-maximizing.

References

|