Finance:Welfare cost of business cycles

In macroeconomics, the cost of business cycles is the decrease in social welfare, if any, caused by business cycle fluctuations.

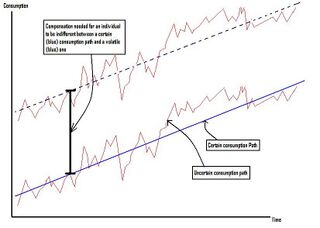

Nobel economist Robert Lucas proposed measuring the cost of business cycles as the percentage increase in consumption that would be necessary to make a representative consumer indifferent between a smooth, non-fluctuating, consumption trend and one that is subject to business cycles.

Under the assumptions that business cycles represent random shocks around a trend growth path, Robert Lucas argued that the cost of business cycles is extremely small,[1][2] and as a result the focus of both academic economists and policy makers on economic stabilization policy rather than on long term growth has been misplaced.[3][4] Lucas himself, after calculating this cost back in 1987, reoriented his own macroeconomic research program away from the study of short run fluctuations.[citation needed]

However, Lucas' conclusion is controversial. In particular, Keynesian economists typically argue that business cycles should not be understood as fluctuations above and below a trend. Instead, they argue that booms are times when the economy is near its potential output trend, and that recessions are times when the economy is substantially below trend, so that there is a large output gap.[4][5] Under this viewpoint, the welfare cost of business cycles is larger, because an economy with cycles not only suffers more variable consumption, but also lower consumption on average.

Basic intuition

If we consider two consumption paths, each with the same trend and the same initial level of consumption – and as a result same level of consumption per period on average – but with different levels of volatility, then, according to economic theory, the less volatile consumption path will be preferred to the more volatile one. This is due to risk aversion on part of individual agents. One way to calculate how costly this greater volatility is in terms of individual (or, under some restrictive conditions, social) welfare is to ask what percentage of her annual average consumption would an individual be willing to sacrifice in order to eliminate this volatility entirely. Another way to express this is by asking how much an individual with a smooth consumption path would have to be compensated in terms of average consumption in order to accept the volatile path instead of the one without the volatility. The resulting amount of compensation, expressed as a percentage of average annual consumption, is the cost of the fluctuations calculated by Lucas. It is a function of people's degree of risk aversion and of the magnitude of the fluctuations which are to be eliminated, as measured by the standard deviation of the natural log of consumption.[6]

Lucas' formula

Robert Lucas' baseline formula for the welfare cost of business cycles is given by (see mathematical derivation below):

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda=\frac {1} {2} \sigma^2 \theta }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math] is the cost of fluctuations (the % of average annual consumption that a person would be willing to pay to eliminate all fluctuations in her consumption), [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] is the standard deviation of the natural log of consumption and [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math] measures the degree of relative risk aversion.[6]

It is straightforward to measure [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] from available data. Using United States data from between 1947 and 2001 Lucas obtained [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma=.032 }[/math]. It is a little harder to obtain an empirical estimate of [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math]; although it should be theoretically possible, many controversies in economics revolve around the precise and appropriate measurement of this parameter. However it is doubtful that [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math] is particularly high (most estimates are no higher than 4).

As an illustrative example consider the case of log utility (see below) in which case [math]\displaystyle{ \theta=1 }[/math]. In this case the welfare cost of fluctuations is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda=\frac {1} {2} (.032)^2 = .0005 . }[/math]

In other words, eliminating all the fluctuations from a person's consumption path (i.e., eliminating the business cycle entirely) is worth only 1/20 of 1 percent of average annual consumption. For example, an individual who consumes $50,000 worth of goods a year on average would be willing to pay only $25 to eliminate consumption fluctuations.

The implication is that, if the calculation is correct and appropriate, the ups and downs of the business cycles, the recessions and the booms, hardly matter for individual and possibly social welfare. It is the long run trend of economic growth that is crucial.

If [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math] is at the upper range of estimates found in literature, around 4, then

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda=\frac {1} {2} (.032)^2 4 = .002 }[/math]

or 1/5 of 1 percent. An individual with average consumption of $50,000 would be willing to pay $100 to eliminate fluctuations. This is still a very small amount compared to the implications of long run growth on income.

One way to get an upper bound on the degree of risk aversion is to use the Ramsey model of intertemporal savings and consumption. In that case, the equilibrium real interest rate is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ r = \rho +\theta g }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] is the real (after tax) rate of return on capital (the real interest rate), [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] is the subjective rate of time preference (which measures impatience) and [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] is the annual growth rate of consumption. [math]\displaystyle{ r }[/math] is generally estimated to be around 5% (.05) and the annual growth rate of consumption is about 2% (.02). Then the upper bound on the cost of fluctuations occurs when [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math] is at its highest, which in this case occurs if [math]\displaystyle{ \rho=0 }[/math]. This implies that the highest possible degree of risk aversion is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \theta^{Max}=r/g=.05/.02=2.5 }[/math]

which in turn, combined with estimates given above, yields a cost of fluctuations as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda=\frac {1} {2} (.032)^2 2.5 = .0013 }[/math]

which is still extremely small (13% of 1%).

Mathematical representation and formula

Lucas sets up an infinitely lived representative agent model where total lifetime utility ([math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math]) is given by the present discounted value (with [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math] representing the discount factor) of per period utilities ([math]\displaystyle{ u(.) }[/math]) which in turn depend on consumption in each period ([math]\displaystyle{ c_t }[/math])[4]

- [math]\displaystyle{ U=\sum_{t=0}^\infty \beta^t u(c_t) }[/math]

In the case of a certain consumption path, consumption in each period is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ c_t^{cert}=A e^{gt} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] is initial consumption and [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] is the growth rate of consumption (neither of these parameters turns out to matter for costs of fluctuations in the baseline model, so they can be normalized to 1 and 0 respectively).

In the case of a volatile, uncertain consumption path, consumption in each period is given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ c_t^{vol}=(1+\lambda) A e^{gt} e^{-\frac {1} {2} \sigma^2} \epsilon_t }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] is the standard deviation of the natural log of consumption and [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math] is a random shock which is assumed to be log-normally distributed so that the mean of [math]\displaystyle{ ln (\epsilon_t) }[/math] is zero, which in turn implies that the expected value of [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-\frac {1} {2} \sigma^2} \epsilon_t }[/math] is 1 (i.e., on average, volatile consumption is same as certain consumption). In this case [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math] is the "compensation parameter" which measures the percentage by which average consumption has to be increased for the consumer to be indifferent between the certain path of consumption and the volatile one. [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math] is the cost of fluctuations.

We find this cost of fluctuations by setting

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_{t=0}^\infty \beta^t u(c_t^{cert}) = \sum_{t=0}^\infty \beta^t u(c_t^{vol}) }[/math]

and solving for [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math]

For the case of isoelastic utility, given by

- [math]\displaystyle{ u(c_t) = \frac{c_t^{1-\theta}-1}{1-\theta} }[/math]

we can obtain an (approximate) closed form solution which has already been given above

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda=\frac {1} {2} \sigma^2 \theta }[/math]

A special case of the above formula occurs if utility is logarithmic, [math]\displaystyle{ u(c_t)=ln(c_t) }[/math] which corresponds to the case of [math]\displaystyle{ \theta=1 }[/math], which means that the above simplifies to [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda=.5 \sigma^2 }[/math]. In other words, with log utility the cost of fluctuations is equal to one half the variance of the natural logarithm of consumption.[6]

An alternative, more accurate solution gives losses that are somewhat larger, especially when volatility is large.[7]

However, a major problem related to the above way of estimating [math]\displaystyle{ \theta }[/math] (hence [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math]) and in fact, possibly to Lucas' entire approach is the so-called equity premium puzzle, first observed by Mehra and Prescott in 1985.[8] The analysis above implies that since macroeconomic risk is unimportant, the premium associated with systematic risk, that is, risk in returns to an asset that is correlated with aggregate consumption should be small (less than 0.5 percentage points for the values of risk aversion considered above). In fact the premium has averaged around six percentage points.

In a survey of the implications of the equity premium, Simon Grant and John Quiggin note that 'A high cost of risk means that recessions are extremely destructive'.[9]

Evidence from effects on subjective wellbeing

Justin Wolfers has shown that macroeconomic volatility reduces subjective wellbeing; the effects are somewhat larger than expected under the Lucas approach. According to Wolfers, 'eliminating unemployment volatility would raise well-being by an amount roughly equal to that from lowering the average level of unemployment by a quarter of a percentage point'.[10]

See also

- Welfare cost of inflation

- Unemployment#Costs

- Economic stability

References

- ↑ Otrok, Christopher (2001). "On measuring the welfare cost of business cycles". Journal of Monetary Economics 47 (1): 61–92. doi:10.1016/S0304-3932(00)00052-0. http://fmwww.bc.edu/RePEc/es2000/1094.pdf.

- ↑ Imrohoroglu, Ayse. "welfare costs of business cycles". The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics Online. http://www.econ.nyu.edu/user/violante/NYU%20Teaching/Topics/Fall2008/imrohoroglu-palgrave.pdf.

- ↑ Barlevy, Gadi (2004). "The Cost of Business Cycles under Endogenous Growth". American Economic Review 94 (4): 964–990. doi:10.1257/0002828042002615. http://www.nber.org/papers/w9970.pdf.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 Yellen, Janet L.; Akerlof, George A. (January 1, 2006). "Stabilization policy: a reconsideration". Economic Inquiry 44: 1–22. doi:10.1093/ei/cbj002. http://www.accessmylibrary.com/coms2/summary_0286-12720438_ITM.

- ↑ Galí, Jordi; Gertler, Mark; López-Salido, J. David (2007). "Markups, Gaps, and the Welfare Costs of Business Fluctuations". Review of Economics and Statistics 98 (1): 44–59. doi:10.1162/rest.89.1.44.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 Lucas, Robert E. Jr. (2003). "Macroeconomic Priorities". American Economic Review 93 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1257/000282803321455133.

- ↑ Latty (2011) A note on the relationship between the Atkinson index and the Generalised entropy class of decomposable inequality indexes under the assumption of log-normality of income distribution or volatility, https://www.academia.edu/1816869/A_note_on_the_relationship_between_the_Atkinson_index_and_the_generalised_entropy_class_of_decomposable_inequality_indexes_under_the_assumption_of_log-normality_of_income_distribution_or_volatility

- ↑ Mehra, Rajnish; Prescott, Edward C. (1985). "The Equity Premium: A Puzzle". Journal of Monetary Economics 15 (2): 145–161. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(85)90061-3. http://minneapolisfed.org/research/sr/sr81.pdf.

- ↑ Grant, Simon; Quiggin, John (2005). "What does the equity premium mean?". The Economists' Voice 2 (4): Article 2. doi:10.2202/1553-3832.1088. http://www.bepress.com/ev/vol2/iss4/art2.

- ↑ Wolfers, Justin (April 2003). "Is Business Cycle Volatility Costly? Evidence from Surveys of Subjective Wellbeing". National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w9619.

Further reading

- Lucas, Robert E. Jr. (1987). Models of Business Cycles. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-14789-3. https://archive.org/details/modelsofbusiness0000luca.

|