Geometry of roots of real polynomials

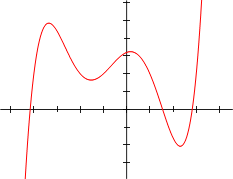

ƒ(x) = 1/20 (x + 4)(x + 2)· ·(x + 1)(x − 1)(x − 3) + 2

Graphical methods provide a means of determining or approximating the roots of a polynomial—the values that make the polynomial equal to zero.[1] Practical tools for performing these include graph paper, graphical calculators and computer graphics.[2]

The fundamental theorem of algebra states that a nth-degree polynomial with complex coefficients (including real coefficients) has n complex roots (not necessarily real even if the coefficients are real), although its roots may not all be different from each other. If the polynomial has real coefficients, its roots are either real, or else occur as complex conjugates. Suppose a polynomial P(x) is graphed as y = P(x). At a real root, the graph of the polynomial crosses the x-axis. Thus, the real roots of a polynomial can be demonstrated graphically.[3]

For some kinds of polynomials, all the roots, including the complex roots, can be found graphically. Polynomial equations up to the fifth degree may be solved graphically.[4][5][6]

The geometrical methods of ruler and compass may be used to solve any linear or quadratic equation. Descartes showed that the constructions of Euclid were equivalent to the algebraic solution of quadratics.[7]

Cubic equations may be solved by solid geometry. Archimedes' work On the Sphere and the Cylinder provided solutions of some cubics and Omar Khayyam systematised this to provide geometrical solutions of all quadratics and cubics.[8]

Complex roots of quadratic polynomials

For polynomials with real coefficients, a local minimum point above the x-axis or a local maximum point below the x-axis indicates the existence of two non-real complex roots, which are each other's complex conjugates.[9] The converse, however, is not true; for example, the cubic polynomial x3 + x has two complex roots, but its graph has no local minima or maxima.

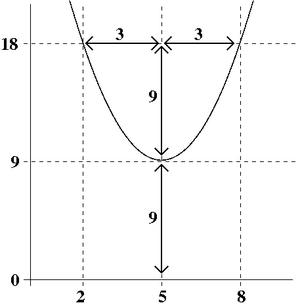

The simplest such case involves parabolas.

If a parabola has a global minimum point above the x-axis, or a global maximum point below the x-axis, then its x intercepts are not real. For

if a and k are positive, then the roots are non-real complex numbers. The number k is then the height of the vertex above the x-axis. In the example in the illustration, we have k = 9. Suppose one goes k units in the opposite direction from the vertex, i.e. away from the x-axis, then horizontally as far as it takes to reach the curve (in the example, that distance is 3. The horizontal distance from that point to the curve is the absolute value of the imaginary part of the root.[10] The x-coordinate of the vertex is the real part.[10] Thus, in the example, the roots are[10]

This method is specific to quadratics and does not generalise to higher-degree polynomial equations.

See also

References

- ↑ James A. Ward (April 1937), "Graphical Representation of Complex Roots", National Mathematics Magazine 11 (7): 297–303, doi:10.2307/3028785

- ↑ Robert Kowalski, Helen Skala (1990), "Determining Roots of Complex Functions with Computer Graphics", Coll. Micro. VIII (1): 51–54

- ↑ Sudhir Kumar Goel, Denise T. Reid. (December 2001), "A graphical approach to understanding the fundamental theorem of algebra", Mathematics Teacher 94 (9): 749

- ↑ Henriquez, Garcia, "The graphical interpretation of the complex roots of cubic equations," American Mathematical Monthly 42(6), June–July 1935, 383-384.

- ↑ George A. Yanosik (January 1943), "Graphical Solutions for Complex Roots of Quadratics, Cubics and Quartics", National Mathematics Magazine 17 (4): 147–150, doi:10.2307/3028335

- ↑ T.W.Chaundy (1934), "On the number of real roots of a quintic equation", The Quarterly Journal of Mathematics (Oxford University Press) os-5: 10–22, doi:10.1093/qmath/os-5.1.10

- ↑ Robin Hartshorne (2000), Geometry: Euclid and beyond, pp. 120 et seq., ISBN 978-0-387-98650-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=EJCSL9S6la0C

- ↑ John N. Crossley (1987), "ch. III Latency", The emergence of number, ISBN 978-9971-5-0414-4, https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=4miP1_qN7aoC

- ↑ Stedall, Jacqueline A. (2011), From Cardano's Great Art to Lagrange's Reflections: Filling a Gap in the History of Algebra, Heritage of European mathematics, European Mathematical Society, p. 97, ISBN 9783037190920, https://books.google.com/books?id=VQ-eI3EHBD4C&pg=PA97.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Alec Norton, Benjamin Lotto (June 1984), "Complex Roots Made Visible", The College Mathematics Journal 15 (3): 248–249, doi:10.2307/2686333

External links

- Complex roots made visible at Mudd Math Fun Facts

- Connecting complex roots to a parabola's graph at ON-Math

- Complex Roots at Dr. Math. With comments by John Conway