Golomb ruler

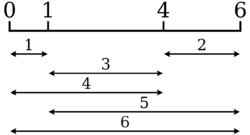

In mathematics, a Golomb ruler is a set of marks at integer positions along a ruler such that no two pairs of marks are the same distance apart. The number of marks on the ruler is its order, and the largest distance between two of its marks is its length. Translation and reflection of a Golomb ruler are considered trivial, so the smallest mark is customarily put at 0 and the next mark at the smaller of its two possible values. Golomb rulers can be viewed as a one-dimensional special case of Costas arrays.

The Golomb ruler was named for Solomon W. Golomb and discovered independently by (Sidon 1932)[1] and (Babcock 1953). Sophie Piccard also published early research on these sets, in 1939, stating as a theorem the claim that two Golomb rulers with the same distance set must be congruent. This turned out to be false for six-point rulers, but true otherwise.[2]

There is no requirement that a Golomb ruler be able to measure all distances up to its length, but if it does, it is called a perfect Golomb ruler. It has been proved that no perfect Golomb ruler exists for five or more marks.[3] A Golomb ruler is optimal if no shorter Golomb ruler of the same order exists. Creating Golomb rulers is easy, but proving the optimal Golomb ruler (or rulers) for a specified order is computationally very challenging.

Distributed.net has completed distributed massively parallel searches for optimal order-24 through order-28 Golomb rulers, each time confirming the suspected candidate ruler.[4][5][6][7][8]

Currently, the complexity of finding optimal Golomb rulers (OGRs) of arbitrary order n (where n is given in unary) is unknown.[clarification needed] In the past there was some speculation that it is an NP-hard problem.[3] Problems related to the construction of Golomb rulers are provably shown to be NP-hard, where it is also noted that no known NP-complete problem has similar flavor to finding Golomb rulers.[9]

Definitions

Golomb rulers as sets

A set of integers where is a Golomb ruler if and only if

The order of such a Golomb ruler is and its length is . The canonical form has and, if , . Such a form can be achieved through translation and reflection.

Golomb rulers as functions

An injective function with and is a Golomb ruler if and only if

- [11]: 236

The order of such a Golomb ruler is and its length is . The canonical form has

- if .

Optimality

A Golomb ruler of order m with length n may be optimal in either of two respects:[11]: 237

- It may be optimally dense, exhibiting maximal m for the specific value of n,

- It may be optimally short, exhibiting minimal n for the specific value of m.

The general term optimal Golomb ruler is used to refer to the second type of optimality.

Practical applications

Information theory and error correction

Golomb rulers are used within information theory related to error correcting codes.[13]

Radio frequency selection

Golomb rulers are used in the selection of radio frequencies to reduce the effects of intermodulation interference with both terrestrial[14] and extraterrestrial[15] applications.

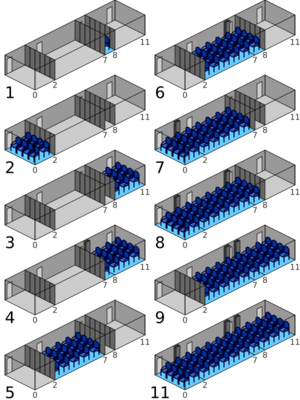

Radio antenna placement

Golomb rulers are used in the design of phased arrays of radio antennas. In radio astronomy one-dimensional synthesis arrays can have the antennas in a Golomb ruler configuration in order to obtain minimum redundancy of the Fourier component sampling.[16][17]

Current transformers

Multi-ratio current transformers use Golomb rulers to place transformer tap points.[citation needed]

Methods of construction

A number of construction methods produce asymptotically optimal Golomb rulers.

Erdős–Turán construction

The following construction, due to Paul Erdős and Pál Turán, produces a Golomb ruler for every odd prime p.[12]

Known optimal Golomb rulers

The following table contains all known optimal Golomb rulers, excluding those with marks in the reverse order. The first four are perfect.

| Order | Length | Marks | Proved[*] | Proof discovered by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1952[18] | Wallace Babcock |

| 2 | 1 | 0 1 | 1952[18] | Wallace Babcock |

| 3 | 3 | 0 1 3 | 1952[18] | Wallace Babcock |

| 4 | 6 | 0 1 4 6 | 1952[18] | Wallace Babcock |

| 5 | 11 | 0 1 4 9 11 0 2 7 8 11 |

c. 1967[19] | John P. Robinson and Arthur J. Bernstein |

| 6 | 17 | 0 1 4 10 12 17 0 1 4 10 15 17 0 1 8 11 13 17 0 1 8 12 14 17 |

c. 1967[19] | John P. Robinson and Arthur J. Bernstein |

| 7 | 25 | 0 1 4 10 18 23 25 0 1 7 11 20 23 25 0 1 11 16 19 23 25 0 2 3 10 16 21 25 0 2 7 13 21 22 25 |

c. 1967[19] | John P. Robinson and Arthur J. Bernstein |

| 8 | 34 | 0 1 4 9 15 22 32 34 | 1972[19] | William Mixon |

| 9 | 44 | 0 1 5 12 25 27 35 41 44 | 1972[19] | William Mixon |

| 10 | 55 | 0 1 6 10 23 26 34 41 53 55 | 1972[19] | William Mixon |

| 11 | 72 | 0 1 4 13 28 33 47 54 64 70 72 0 1 9 19 24 31 52 56 58 69 72 |

1972[19] | William Mixon |

| 12 | 85 | 0 2 6 24 29 40 43 55 68 75 76 85 | 1979[19] | John P. Robinson |

| 13 | 106 | 0 2 5 25 37 43 59 70 85 89 98 99 106 | 1981[19] | John P. Robinson |

| 14 | 127 | 0 4 6 20 35 52 59 77 78 86 89 99 122 127 | 1985[19] | James B. Shearer |

| 15 | 151 | 0 4 20 30 57 59 62 76 100 111 123 136 144 145 151 | 1985[19] | James B. Shearer |

| 16 | 177 | 0 1 4 11 26 32 56 68 76 115 117 134 150 163 168 177 | 1986[19] | James B. Shearer |

| 17 | 199 | 0 5 7 17 52 56 67 80 81 100 122 138 159 165 168 191 199 | 1993[19] | W. Olin Sibert |

| 18 | 216 | 0 2 10 22 53 56 82 83 89 98 130 148 153 167 188 192 205 216 | 1993[19] | W. Olin Sibert |

| 19 | 246 | 0 1 6 25 32 72 100 108 120 130 153 169 187 190 204 231 233 242 246 | 1994[19] | Apostolos Dollas, William T. Rankin and David McCracken |

| 20 | 283 | 0 1 8 11 68 77 94 116 121 156 158 179 194 208 212 228 240 253 259 283 | 1997?[19] | Mark Garry, David Vanderschel et al. (web project) |

| 21 | 333 | 0 2 24 56 77 82 83 95 129 144 179 186 195 255 265 285 293 296 310 329 333 | 8 May 1998[20] | Mark Garry, David Vanderschel et al. (web project) |

| 22 | 356 | 0 1 9 14 43 70 106 122 124 128 159 179 204 223 253 263 270 291 330 341 353 356 | 1999[19] | Mark Garry, David Vanderschel et al. (web project) |

| 23 | 372 | 0 3 7 17 61 66 91 99 114 159 171 199 200 226 235 246 277 316 329 348 350 366 372 | 1999[19] | Mark Garry, David Vanderschel et al. (web project) |

| 24 | 425 | 0 9 33 37 38 97 122 129 140 142 152 191 205 208 252 278 286 326 332 353 368 384 403 425 | 13 October 2004[4] | distributed.net |

| 25 | 480 | 0 12 29 39 72 91 146 157 160 161 166 191 207 214 258 290 316 354 372 394 396 431 459 467 480 | 25 October 2008[5] | distributed.net |

| 26 | 492 | 0 1 33 83 104 110 124 163 185 200 203 249 251 258 314 318 343 356 386 430 440 456 464 475 487 492 | 24 February 2009[6] | distributed.net |

| 27 | 553 | 0 3 15 41 66 95 97 106 142 152 220 221 225 242 295 330 338 354 382 388 402 415 486 504 523 546 553 | 19 February 2014[7] | distributed.net |

| 28 | 585 | 0 3 15 41 66 95 97 106 142 152 220 221 225 242 295 330 338 354 382 388 402 415 486 504 523 546 553 585 | 23 November 2022[8] | distributed.net |

^ * The optimal ruler would have been known before this date; this date represents that date when it was discovered to be optimal (because all other rulers were proved to not be smaller). For example, the ruler that turned out to be optimal for order 26 was recorded on 10 October 2007, but it was not known to be optimal until all other possibilities were exhausted on 24 February 2009.

See also

References

- ↑ Sidon, S. (1932). "Ein Satz über trigonometrische Polynome und seine Anwendungen in der Theorie der Fourier-Reihen". Mathematische Annalen 106: 536–539. doi:10.1007/BF01455900.

- ↑ Bekir, Ahmad (2007). "There are no further counterexamples to S. Piccard's theorem". IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 53 (8): 2864–2867. doi:10.1109/TIT.2007.899468..

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Modular and Regular Golomb Rulers". http://cgm.cs.mcgill.ca/~athens/cs507/Projects/2003/JustinColannino.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "distributed.net - OGR-24 completion announcement". 2004-11-01. https://blogs.distributed.net/2004/11/01/10/24/nugget/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "distributed.net - OGR-25 completion announcement". 2008-10-25. https://blogs.distributed.net/2008/10/25/23/14/bovine/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "distributed.net - OGR-26 completion announcement". 2009-02-24. https://blogs.distributed.net/2009/02/24/17/26/bovine/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "distributed.net - OGR-27 completion announcement". 2014-02-25. https://blogs.distributed.net/2014/02/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Completion of OGR-28 project". https://blogs.distributed.net/2022/11/23/03/28/bovine/.

- ↑ Meyer C, Papakonstantinou PA (February 2009). "On the complexity of constructing Golomb rulers". Discrete Applied Mathematics 157 (4): 738–748. doi:10.1016/j.dam.2008.07.006.

- ↑ Dimitromanolakis, Apostolos. "Analysis of the Golomb Ruler and the Sidon Set Problems, and Determination of Large, Near-Optimal Golomb Rulers". http://www.cs.toronto.edu/%7Eapostol/golomb/main.pdf.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Drakakis, Konstantinos (2009). "A Review Of The Available Construction Methods For Golomb Rulers". Advances in Mathematics of Communications 3 (3): 235–250. doi:10.3934/amc.2009.3.235.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Erdős, Paul; Turán, Pál (1941). "On a problem of Sidon in additive number theory and some related problems". Journal of the London Mathematical Society 16 (4): 212–215. doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-16.4.212.

- ↑ Robinson J, Bernstein A (January 1967). "A class of binary recurrent codes with limited error propagation". IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 13 (1): 106–113. doi:10.1109/TIT.1967.1053951.

- ↑ Babcock, Wallace C. (1953). "Intermodulation Interference in Radio Systems" (excerpt). Bell System Technical Journal 32: 63–73. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1953.tb01422.x. http://www.alcatel-lucent.com/bstj/vol32-1953/articles/bstj32-1-63.pdf. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- ↑ Fang, R. J. F.; Sandrin, W. A. (1977). "Carrier frequency assignment for nonlinear repeaters". Comsat Technical Review 7: 227. Bibcode: 1977COMTR...7..227F.

- ↑ Thompson, A. Richard; Moran, James M.; Swenson, George W. (2004). Interferometry and Synthesis in Radio Astronomy (Second ed.). Wiley-VCH. p. 142. ISBN 978-0471254928. https://archive.org/details/interferometrysy00thom_120.

- ↑ Arsac, J. (1955). "Transmissions des frequences spatiales dans les systemes recepteurs d'ondes courtes" (in fr). Optica Acta 2 (112): 112–118. doi:10.1080/713821025. Bibcode: 1955AcOpt...2..112A.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Rulers, Arrays, and Gracefulness Ed Pegg Jr. November 15, 2004. Math Games.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 19.13 19.14 19.15 19.16 19.17 Shearer, James B (19 February 1998). "Table of lengths of shortest known Golomb rulers". IBM. http://www.research.ibm.com/people/s/shearer/grtab.html.

- ↑ "In Search Of The Optimal 20 & 21 Mark Golomb Rulers (archived)". Mark Garry, David Vanderschel, et al. 26 November 1998. http://members.aol.com/golomb20/index.html.

- Gardner, Martin (March 1972). "Mathematical games". Scientific American 226 (3): 108–112. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0372-108. Bibcode: 1972SciAm.226c.108G.

External links

- James B. Shearer's Golomb ruler pages

- distributed.net: Project OGR

- In Search Of The Optimal 20, 21 & 22 Mark Golomb Rulers

- Golomb rulers up to length of over 200

|