History:Bindusara

| Bindusara | |

|---|---|

A silver coin of 1 karshapana of the Maurya empire, period of Bindusara Maurya about 297–273 BC, workshop of Pataliputra. Obv: Symbols with a Sun Rev: Symbol Dimensions: 14 x 11 mm Weight: 3.4 g. | |

| 2nd Mauryan Emperor | |

| Reign | c. 297 – c. 273 BCE |

| Coronation | c. 297 BCE |

| Predecessor | Chandragupta Maurya (father) |

| Successor | Ashoka (son) |

| Died | c. 273 BCE |

| Spouse | Dharma |

| Issue | Susima, Ashoka, Vitashoka |

| Dynasty | Maurya |

| Father | Chandragupta Maurya |

| Mother | Durdhara (according to Jain tradition) |

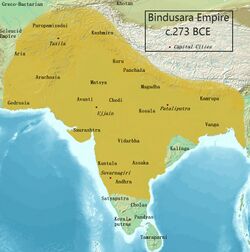

Bindusara (r. c. 297 – c. 273 BCE), also Amitraghāta or Amitrakhāda (Sanskrit: अमित्रघात, "slayer of enemies" or "devourer of enemies")[1][2] or Amitrochates (Greek: Ἀμιτροχάτης)[2] was the second Mauryan emperor of India. He was the son of the dynasty's founder Chandragupta and the father of its most famous ruler Ashoka. Bindusara's life is not documented as well as the lives of these two emperors: much of the information about him comes from legendary accounts written several hundred years after his death.

Bindusara consolidated the empire created by his father. The 16th century Tibetan Buddhist author Taranatha credits his administration with extensive territorial conquests in southern India, but some historians doubt the historical authenticity of this claim.

Background

Ancient and medieval sources have not documented Bindusara's life in detail. Much of the information about him comes from Jain legends focused on Chandragupta and the Buddhist legends focused on Ashoka. The Jain legends, such as Hemachandra's Parishishta-Parvan were written more than a thousand years after his death.[3] Most of the Buddhist legends about Ashoka's early life also appear to have been composed by Buddhist writers who lived several hundred years after Ashoka's death, and are of little historical value.[4] While these legends can be used to make several inferences about Bindusara's reign, they are not entirely reliable because of the close association between Ashoka and Buddhism.[3]

Buddhist sources that provide information about Bindusara include Divyavadana (including Ashokavadana and Pamsupradanavadana), Dipavamsa, Mahavamsa, Vamsatthappakasini (also known as Mahvamsa Tika or "Mahavamsa commentary"), Samantapasadika, and the 16th century writings of Taranatha.[5][6][7] The Jain sources include the 12th century Parishishta-Parvan by Hemachandra and the 19th century Rajavali-Katha by Devachandra.[8][9] The Hindu Puranas also mention Bindusara in their genealogies of Mauryan rulers.[10] Some Greek sources also mention him by the name "Amitrochates" or its variations.[11][8]

Early life

Parents

Bindusara was born to Chandragupta, the founder of the Mauryan Empire. This is attested by several sources, including the various Puranas and the Mahavamsa.[12] The Dipavamsa, on the other hand, names Bindusara as the son of the king Shushunaga.[5] The prose version of Ashokavadana states that Bindusara was the son of Nanda and a 10th-generation descendant of Bimbisara. Like Dipavamsa, it omits Chandragupta's name altogether. The metrical version of Ashokavadana contains a similar genealogy with some variations.[5]

Chandragupta had a marriage alliance with the Seleucids, which has led to speculation that Bindusara's mother might have been Greek or Macedonian. However, there is no evidence of this.[13] According to the 12th century Jain writer Hemachandra's Parishishta-Parvan, the name of Bindusara's mother was Durdhara.[9]

Names

The name "Bindusara", with slight variations, is attested by the Buddhist texts such as Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa ("Bindusaro"); the Jain texts such as Parishishta-Parvan; as well as the Hindu texts such as Vishnu Purana ("Vindusara").[14][15] Other Puranas give different names for Chandragupta's successor; these appear to be clerical errors.[14] For example, the various recensions of Bhagavata Purana mention him as Varisara or Varikara. The different versions of Vayu Purana call him Bhadrasara or Nandasara.[10]

The Mahabhashya names Chandragupta's successor as Amitra-ghata (Sanskrit for "slayer of enemies").[6] The Greek writers Strabo and Athenaeus call him Allitrochades and Amitrochates respectively; these names are probably derived from the Sanskrit title. In addition, Bindusara was given the title Devanampriya ("The Beloved of the Gods"), which was also applied to his successor Ashoka.[2] The Jain work Rajavali-Katha states that his birth name was Simhasena.[8]

Both Buddhist and Jain texts mention a legend about how Bindusara got his name. Both accounts state that Chandragupta's minister Chanakya used to mix small doses of poison in the emperor's food to build his immunity against possible poisoning attempts. One day, Chandragupta, not knowing about the poison, shared his food with his pregnant wife. According to the Buddhist legends (Mahavamsa and Mahavamsa Tikka), the queen was seven days away from delivery at this time. Chanakya arrived just as the queen ate the poisoned morsel. Realizing that she was going to die, he decided to save the unborn child. He cut off the queen's head and cut open her belly with a sword to take out the foetus. Over the next seven days, he placed the foetus in the belly of a goat freshly killed each day. After seven days, Chandragupta's son was "born". He was named Bindusara, because his body was spotted with drops ("bindu") of goat's blood.[16] The Jain text Parishishta-Parvan names the queen as Durdhara, and states that Chanakya entered the room the very moment she collapsed. To save the child, he cut open the dead queen's womb and took the baby out. By this time, a drop ("bindu") of poison had already reached the baby and touched its head. Therefore, Chanakya named him Bindusara, meaning "the strength of the drop".[9]

Family

The prose version of Ashokavadana names three sons of Bindusara: Sushima, Ashoka and Vigatashoka. The mother of Ashoka and Vigatashoka was a woman named Subhadrangi, the daughter of a Brahmin of the Champa city. When she was born, an astrologer predicted that one of her sons would be a king, and the other a religious man. When she grew up, her father took her to Bindusara's palace in Pataliputra. Bindusara's wives, jealous of her beauty, trained her as the royal barber. Once, when the Emperor was pleased with her hairdressing skills, she expressed her desire to be a queen. Bindusara was initially apprehensive about her low class, but made her the chief queen after learning about her Brahmin descent. The couple had two sons: Ashoka and Vigatashoka. Bindusara did not like Ashoka because his "limbs were hard to the touch".[17]

Another legend in Divyavadana names Ashoka's mother as Janapadakalyani.[18] According to the Vamsatthappakasini (Mahavamsa Tika), the name of Ashoka's mother was Dhamma.[19] The Mahavamsa states that Bindusara had 101 sons from 16 women. The eldest of these was Sumana, and the youngest was Tishya (or Tissa). Ashoka and Tishya were born to the same mother.[12]

Reign

Historian Upinder Singh estimates that Bindusara ascended the throne around 297 BCE.[6]

Territorial conquests

The 16th century Tibetan Buddhist author Taranatha states that Chanakya, one of Bindusara's "great lords", destroyed the nobles and kings of 16 towns and made him master of all the territory between the western and the eastern seas (Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal). According to some historians, this implies conquest of Deccan by Bindusara, while others believe that this only refers to suppression of revolts.[6]

Sailendra Nath Sen notes that the Mauryan empire already extended from the western sea (beside Saurashtra) to the eastern sea (beside Bengal) during Chandragupta's reign. Besides, Ashoka's inscriptions found in southern India do not mention anything about Bindusara's conquest of Deccan (southern India). Based on this, Sen concludes that Bindusara did not extend the Mauryan empire, but managed to retain the territories he inherited from Chandragupta.[20]

K. Krishna Reddy, on the other hand, argues that Ashoka's inscriptions would have boasted about his conquest of southern India, had he captured Deccan. Reddy, therefore, believes that the Mauryan empire extended up to Mysore during Bindusara's reign. According to him, the southernmost kingdoms were not a part of the Mauryan empire, but probably acknowledged its suzerainty.[21]

Alain Daniélou believes that Bindusara inherited an empire that included the Deccan region, and made no territorial additions to the empire. Daniélou, however, believes that Bindusara brought the southern territories of the Cheras, the Cholas and the Satyaputras under nominal Mauryan control, although he could not overcome their armies. His theory is based on the fact that the ancient Tamil literature alludes to Vamba Moriyar (Mauryan conquest), although it does not provide any details about the Mauryan expeditions. According to Daniélou, Bindusara's main achievement was organization and consolidation of the empire he inherited from Chandragupta.[22]

Takshashila revolt

The Mahavamsa suggests that Bindusara appointed his son Ashoka as the viceroy of Ujjayini.[12] Ashokavadana states that Bindusara sent Ashoka to lay siege to Takshashila. The Emperor refused to provide any weapons or chariots for Ashoka's expedition. The devatas (deities) then miraculously brought him soldiers and weapons. When his army reached Takshashila, the residents of the city approached him. They told him that they only opposed Bindusara's oppressive ministers; they had no problem with the Emperor or the prince. Ashoka then entered the city without opposition, and the devatas declared that he would rule the entire earth one day. Shortly before Bindusara's death, there was a second revolt in Takshashila. This time, Sushima was sent to quell the rebellion, but he failed in the task.[17]

Advisors

The Rajavali-Katha states that Chandragupta's chief advisor (or chief minister) Chanakya accompanied him to the forest for retirement, after handing over the administration to Bindusara.[23] However, the Parishishta-Parvan states that Chanakya continued to be Bindusara's prime minister. It mentions a legend about Chanakya's death: Chanakya asked the emperor to appoint a man named Subandhu as one of his ministers. However, Subandhu wanted to become a higher minister and grew jealous of Chanakya. So, he told Bindusara that Chanakya had cut open the belly of his mother. After confirming the story with the nurses, Bindusara started hating Chanakya. As a result, Chanakya, who was already a very old man by this time, retired and decided to starve himself to death. Meanwhile, Bindusara came to know about the detailed circumstances of his birth, and implored Chanakya to resume his ministerial duties. When Chanakya refused to oblige, the Emperor ordered Subandhu to pacify him. Subandhu, while pretending to appease Chanakya, burned him to death. Shortly after this, Subandhu himself had to retire and become a monk due to Chanakya's curse.[9][24]

Ashokavadana suggests that Bindusara had 500 royal councillors. It names two officials – Khallataka and Radhagupta – who helped his son Ashoka became the emperor after his death.[17]

Foreign relations

Deimachus as an ambassador, he was the successor to the famous ambassador and historian Megasthenes. Both of them were mentioned by Strabo.

Both of these men were sent [as] ambassadors to Palimbothra (Pataliputra): Megasthenes to Sandrocottus, Deimachus to Allitrochades his son. -Strabo II,I,9[25]

Bindusara maintained friendly diplomatic relations with the Greeks. Deimachos of Plateia was the ambassador of Seleucid emperor Antiochus I at Bindusara's court.[26][20][27] Deimachos seems to have written a treatise entitled "On Piety" (Peri Eusebeias).[28] The 3rd century Greek writer Athenaeus, in his Deipnosophistae, mentions an incident that he learned from Hegesander's writings: Bindusara requested Antiochus to send him sweet wine, dried figs and a sophist.[11] Antiochus replied that he would send the wine and the figs, but the Greek laws forbade him to sell a sophist.[29][30][31] Bindusara's request for a sophist probably reflects his intention to learn about the Greek philosophy.[32]

Diodorus states that the king of Palibothra (Pataliputra, the Mauryan capital) welcomed a Greek author, Iambulus. This king is usually identified as Bindusara.[20] Pliny states that the Egyptian king Philadelphus sent an envoy named Dionysius to India.[32][33] According to Sailendra Nath Sen, this appears to have happened during Bindusara's reign.[20]

Religion

The Buddhist texts Samantapasadika and Mahavamsa suggest that Bindusara followed Brahmanism, calling him a "Brahmana bhatto" ("votary of the Brahmanas").[7][35] According to the Jain sources, Bindusara's father Chandragupta adopted Jainism before his death. However, they are silent on Bindusara's faith, and there is no evidence to show that Bindusara was a Jain.[36] A fragmentary inscription at Sanchi, in the ruins of the 3rd century BCE Temple 40, perhaps refers to Bindusara, which might suggest his connection with the Buddhist order at Sanchi.[6][34]

Some Buddhist texts mention that an Ajivika astrologer or priest at Bindusara's court prophesied the future greatness of the prince Ashoka.[37] The Pamsupradanavadana (part of Divyavadana) names this man as Pingalavatsa.[38] The Vamsatthappakasini (the Mahavamsa commentary) names this man as Janasana, based on a commentary on Majjhima Nikaya.[7]

The Divyavadana version states that Pingalavatsa was an Ajivika parivrajaka (wandering teacher). Bindusara asked him to assess the ability of the princes to be the next emperor, as the two watched the princes play. Pingalavatsa recognized Ashoka as the most suitable prince, but did not give a definitive answer to the Emperor, since Ashoka was not Bindusara's favourite son. He, however, told Queen Subhadrangi of Ashoka's future greatness. The Queen requested him to leave the kingdom before the Emperor forced him to provide an answer. Pingalavatsa returned to the court after Bindusara's death.[37]

The Mahavamsa commentary states that Janasana (also Jarasona or Jarasana) was the Queen's kulupaga (ascetic of the royal household). He had been born as a python during the period of Kassapa Buddha, and had become very wise after listening to the discussions of the bhikkhus. Based on his observations of the Queen's pregnancy, he prophesied Ashoka's future greatness. He appears to have left the court for unknown reasons. When Ashoka grew up, the Queen told him that Janasana had forecast his greatness. Ashoka then sent a carriage to bring back Janasana, who was residing at an unnamed place far from the capital, Pataliputra. On the way back to Pataliputra, he was converted to Buddhism by one Assagutta.[37]

Based on these legends, scholars such as A. L. Basham conclude that Bindusara patronized the Ajivikas.[37][6]

Death and succession

Historical evidence suggests that Bindusara died in the 270s BCE. According to Upinder Singh, Bindusara died around 273 BCE.[6] Alain Daniélou believes that he died around 274 BCE.[22] Sailendra Nath Sen believes that he died around 273-272 BCE, and that his death was followed by a four-year struggle of succession, after which his son Ashoka became the emperor in 269-268 BCE.[20]

According to the Mahavamsa, Bindusara reigned for 28 years, while according to the Puranas, he ruled for 25 years.[39] The Buddhist text Manjushri-Mula-Kalpa claims that he ruled for 70 years, which is not historically accurate.[40]

All sources agree that Bindusara was succeeded by his son Ashoka, although they provide varying descriptions of the circumstances of this succession. According to the Mahavamsa, Ashoka had been appointed as the viceroy of Ujjain. On hearing about his father's fatal illness, he rushed to the capital, Pataliputra. There, he killed his 99 brothers (leaving only Tishya), and became the new emperor.[12]

According to the prose version of Ashokavadana, Bindusara's favourite son Sushima once playfully threw his gauntlet at the prime minister, Khallataka. The minister thought that Sushima was unworthy of being an emperor. Therefore, he approached the 500 royal councillors, and suggested appointing Ashoka as the emperor after Bindusara's death, pointing out that the devatas had predicted his rise as the universal ruler. Sometime later, Bindusara fell sick and decided to hand over the administration to his successor. He asked his ministers to appoint Sushima as the emperor, and Ashoka as the governor of Takshashila. However, by this time, Sushima had been sent to Takshashila, where he was unsuccessfully trying to quell a rebellion. When the Emperor was on his deathbed, the ministers suggested appointing Ashoka as the temporary emperor, and re-appointing Sushima as the emperor after his return from Takshashila. However, Bindusara became angry when he heard this suggestion. Ashoka then declared that if he was meant to be Bindusara's successor, the devatas would appoint him as the emperor. The devatas then miraculously placed the royal crown on his head, while Bindusara died. When Sushima heard this news, he advanced towards Pataliputra to claim the throne. However, he died after being tricked into a pit of burning charcoal by Ashoka's well-wisher Radhagupta.[17][3]

The Rajavali-Katha states that Bindusara retired after handing over the throne to Ashoka.[23]

In popular culture

- Gerson da Cunha portrayed Bindusara in the 2001 Bollywood film, Aśoka.[41]

- Sameer Dharmadhikari plays the role of Bindusara in the television series, Chakravartin Ashoka Samrat.[42]

- Siddharth Nigam plays Bindusara in the television series Chandra Nandni.[43]

References

- ↑ Chattopadhyaya, Sudhakar (1977) (in en). Bimbisāra to Aśoka: With an Appendix on the Later Mauryas. Roy and Chowdhury. p. 98. https://books.google.com/books?id=e9gcAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "According to the Jaina and the Buddhist traditions Chandragupta had many sons and Bindusara was chosen to succeed him. He also had the title 'Devanampriya'. The Greeks call him Amitrachates, the Sanskrit equivalent of Amitragatha" Murthy, H. V. Sreenivasa (1963) (in en). A History of Ancient India. Bani Prakash Mandir. p. 120. https://books.google.com/books?id=HKkBAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Singh 2008, p. 331-332.

- ↑ Srinivasachariar 1974, pp. lxxxvii-lxxxviii.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Srinivasachariar 1974, p. lxxxviii.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Singh 2008, p. 331.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 S. M. Haldhar (2001). Buddhism in India and Sri Lanka (c. 300 BC to C. 600 AD). Om. p. 38. ISBN 9788186867532. https://books.google.com/books?id=jOkQAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Daniélou 2003, p. 108.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Motilal Banarsidass (1993). "The Minister Cāṇakya, from the Pariśiṣtaparvan of Hemacandra". in Phyllis Granoff. The Clever Adulteress and Other Stories: A Treasury of Jaina Literature. pp. 204–206. ISBN 9788120811508. https://books.google.com/books?id=Po9tUNX0SYAC&pg=PA204.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Guruge 1993, p. 465.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kosmin 2014, p. 35.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Srinivasachariar 1974, p. lxxxvii.

- ↑ Arthur Cotterell (2011). The Pimlico Dictionary of Classical Civilizations. Random House. p. 189. ISBN 9781446466728. https://books.google.com/books?id=3zy_zJdaSSIC&pg=PT189.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Vincent Arthur Smith (1920). Asoka, the Buddhist emperor of India. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9788120613034. https://archive.org/stream/asokabuddhistemp00smitiala#page/18/mode/2up.

- ↑ Rajendralal Mitra (1878). "On the Early Life of Asoka". Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (Asiatic Society of Bengal): 10. https://books.google.com/books?id=rlQOAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA10.

- ↑ Trautmann, Thomas R. (1971). Kauṭilya and the Arthaśāstra: a statistical investigation of the authorship and evolution of the text. Brill. p. 15. https://books.google.com/books?id=v3iDAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Eugène Burnouf (1911). Legends of Indian Buddhism. New York: E. P. Dutton. pp. 20–29. https://archive.org/stream/legendsofindianb00burn#page/20/mode/2up.

- ↑ Singh 2008, p. 332.

- ↑ Sastri 1988, p. 167.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 Sen 1999, p. 142.

- ↑ K Krishna Reddy (2005). General Studies History. New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill. p. A42-43. ISBN 9780070604476. https://books.google.com/books?id=yWfeU9eQd5YC&pg=SL1-PA42.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Daniélou 2003, p. 109.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 B. Lewis Rice (1889). Epigraphia Carnatica, Volume II: Inscriptions and Sravana Belgola. Bangalore: Mysore Government Central Press. p. 9. https://books.google.com/books?id=EMUUAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA9.

- ↑ Hemachandra (1891). Sthavir̂aval̂i charita, or, Pariśishtaparvan. Calcutta: Asiatic Society. pp. 67–68. https://books.google.com/books?id=iSFCAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA62.

- ↑ Strabo II,I,9

- ↑ Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966) (in en). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 38. ISBN 9788120804050. https://books.google.com/books?id=i-y6ZUheQH8C&pg=PA38.

- ↑ Talbert, Richard J. A.; Naiden, Fred S. (2017) (in en). Mercury's Wings: Exploring Modes of Communication in the Ancient World. Oxford University Press. p. 295. ISBN 9780190663285. https://books.google.com/books?id=uEe1DgAAQBAJ&pg=PT295.

- ↑ Erskine, Andrew (2009) (in en). A Companion to the Hellenistic World. John Wiley & Sons. p. 421. ISBN 9781405154413. https://books.google.com/books?id=krJF3rnhQdsC&pg=PA421.

- ↑ Mookerji 1988, p. 38.

- ↑ J. C. McKeown (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780199982110. https://books.google.com/books?id=ADJpAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA99.

- ↑ Athenaeus (of Naucratis) (1854). The Deipnosophists, or, Banquet of the learned of Athenaeus. III. Literally Translated by C. D. Yonge, B. A.. London: Henry G. Bohn. p. 1044. Original Classification Number: 888 A96d tY55 1854. https://books.google.com/books?id=g98IAAAAQAAJ.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Irfan Habib & Vivekanand Jha 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ India, the Ancient Past, Burjor Avari, p.108-109

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Singh, Upinder (2016) (in ar). The Idea of Ancient India: Essays on Religion, Politics, and Archaeology. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9789351506454. https://books.google.com/books?id=zmAlDAAAQBAJ&pg=PT67.

- ↑ Beni Madhab Barua (1968). Asoka and His Inscriptions. 1. The New Age. p. 171. https://books.google.com/books?id=79w9AAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Kanai Lal Hazra (1984). Royal patronage of Buddhism in ancient India. D.K.. p. 58. https://books.google.com/books?id=ooUEAAAAYAAJ.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Basham, A.L. (1951). History and Doctrines of the Ājīvikas (2nd ed.). Luzac & Company. pp. 146–147. ISBN 81-208-1204-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=BiGQzc5lRGYC.

- ↑ Guruge 1993, p. 27.

- ↑ Romila Thapar 1961, p. 13.

- ↑ Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya (1977). Bimbisāra to Aśoka: With an Appendix on the Later Mauryas. Roy and Chowdhury. p. 102. https://books.google.com/books?id=e9gcAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Sukanya Verma (24 October 2001). "Asoka". rediff.com. http://m.rediff.com/movies/2001/oct/24slide1.htm.

- ↑ "Happy Birthday Sameer Dharamadhikari", The Times of India, 25 September 2015, http://m.timesofindia.com/tv/news/hindi/happy-birthday-sameer-dharamadhikari/Raja-Bindusara-turns-37-today/photostory/49104437.cms

- ↑ "Avneet Kaur joins 'Chandra Nandni' opposite Siddharth Nigam". ABP Live. 10 August 2017. http://www.abplive.in/television/avneet-kaur-joins-chandra-nandni-opposite-siddharth-nigam-563694.

Bibliography

- Daniélou, Alain (2003). A Brief History of India. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-59477-794-3. https://archive.org/details/briefhistoryofin00dani.

- Guruge, Ananda W. P. (1993). Aśoka, the Righteous: A Definitive Biography. Central Cultural Fund, Ministry of Cultural Affairs and Information. ISBN 978-955-9226-00-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=dwjjAAAAMAAJ.

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014), The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0, https://books.google.com/books?id=9UWdAwAAQBAJ

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988), Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0433-3, https://books.google.com/books?id=i-y6ZUheQH8C

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1988). Age of the Nandas and Mauryas. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120804661. https://books.google.com/books?id=YoAwor58utYC&pg=PA165.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. ISBN 9788122411980. https://books.google.com/books?id=Wk4_ICH_g1EC&pg=PA172.

- Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=H3lUIIYxWkEC&pg=PA331.

- Srinivasachariar, M. (1974). History of Classical Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120802841. https://books.google.com/books?id=4dVRvVyHaiQC&pg=PR87.

- Irfan Habib; Vivekanand Jha (2004). Mauryan India. A People's History of India. Aligarh Historians Society / Tulika Books. ISBN 978-81-85229-92-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=nUvGQgAACAAJ.

- Romila Thapar (1961). Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas. Oxford University Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=pwJuAAAAMAAJ.