History:Yugra

Yugra or Yugor Land[1] (Russian: Югра, Югорский край; also spelled Iuhra in contemporary sources) was a collective name for lands and peoples in the region east of the northern Ural Mountains in modern Russia given by Russian chroniclers in the 12th to 17th centuries. During this period, the region was inhabited by the Khanty (Ostyaks) and Mansi (Voguls) peoples.

In a modern context, the term Yugra generally refers to a political constituent of the Russian Federation formally known as Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra, located in the lands historically known as Ioughoria. In modern Russian, this word is rendered "Югория" (Yugoria), and is used as a poetic synonym of the region.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the similarity between Yugria (the latinized form of the name) and ugry, an old Russian ethnonym for the Hungarians, was noted by scholars such as Maciej Miechowita. The modern name of the Ugric language family, which includes Khanty and Mansi together with Hungarian, was also adopted on the assumption that the two words share a common origin.[2] However, even though the linguistic connection between the Ugric languages is well established, the etymological connection between Yugra and ugry is disputed.[3] András Róna-Tas has suggested that the name Yugria is related to the 10th–11th century ethnic name Ugur, whereas the Hungarian ethnonym derives from On Ugur ('ten Oghurs').Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

History

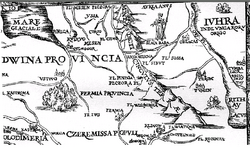

The Novgorodians were aware of the lands of Yugra from at least the 11th century, if not earlier, and launched expeditions to the region;[4] the first mention of Siberia in chronicles is recorded in the year 1032.[5] The term Yugra was first used in the 12th century.[6] Novgorod established two trade routes to the Ob River, both starting from the town of Ustyug.[5] The first route went along the Sukhona and Vychegda, then along the Usa to the lower reaches of the Ob.[5] The second route went down the Northern Dvina, then along the coasts of the White Sea and Kara Sea, before reaching the mouth of the Ob.[5]

The 12th-century missionary and traveller Abu Hamid al-Gharnati also gives one of the earliest accounts of the region, which he calls Yura in Arabic:

But beyond Wisu by the Sea of Darkness there lies a land known by the name of Yura. In summers the days are very long there, so that the Sun does not set for forty days, as the merchants say; but in winters the nights are equally long. The merchants report that Darkness is not far (from them), and that the people of Yura go there and enter it with torches, and find a huge tree there which is like a big village. But on top of the tree there sits a large creature, they say it is a bird. And they bring merchandise along, and each merchant sets down his goods apart from those of the others; and he makes a mark on them and leaves, but when he comes back, he finds commodities there, necessary for his own country ... (Al Garnati:32)

The Russians were attracted to Siberia by its furs, and the Novgorodians traded iron artefacts and textiles for fur.[5] Yugorshchina, a trade association, was set up in Novgorod in the 14th century.[5] The Novgorodians also launched military campaigns to extract tribute from the local population, but they often met resistance, such as in two expeditions in 1187 and 1193 mentioned in chronicles that were defeated.[5] After Novgorod was annexed by Moscow in the 15th century, the newly emerging centralized Russian state also laid claim to the region, with Ivan III of Russia sending a large expeditionary force to Siberia in 1483 led by Fyodor Kurbsky, and another one in 1499–1500 under the command of Semyon Kurbsky.[7] The Russians received tribute from the tribes, but contact with the tribes ceased after they left.[8]

The Golden Lady of the Obians was apparently an idol of the Yugrans. The first reports of the Golden Lady are found in the 14th-century Novgorod Chronicle, with reference to Saint Stephan of Perm. Next, the golden idol is mentioned in the 16th century by the subjects of the grand prince of Moscow, commissioned to describe the trade and military routes of the expanding Russian state. The first non-Russian known to have examined the Golden Lady is Maciej Miechowita, a professor at Cracow University. The golden idol appeared on Sigismund von Herberstein's map of Moscovia published in 1549, and on a number of later maps, such as Gerhard Mercator's Map of the Arctic (1595), where it is labeled Zolotaia Baba (from Russian Золотая баба – "Golden Lady" or "Golden Idol").

In connection with Yermak's campaign, the Siberian Chronicles also mention the Golden Lady: a hetman of Yermak's, by the name of Ivan Bryazga, invaded the Belogorye region in 1582 and fought the Ob-Ugrians there, who were defending their holiest object – the Golden Lady.[9] Grigori Novitski's statement that in earlier days there used to be in one shrine in Belogorye together with the copper goose "the greatest real idol", and that the superstitious people "preserved that idol and took it to Konda now that idol-worshipping is being rooted up", has also been regarded as relating to the Golden Lady.[10]

Of the "Copper Goose" Novitski wrote the following:

The goose idol very much worshipped by them is cast of copper in the shape of a goose, its atrocious abode is in the Belogorye village on the great river of Ob. According to their superstition they worship the god of waterfowls – swans, geese and other birds swimming on water ... His throne in the temple is made of different kinds of broadcloth, canvas and hide, built like a nest; in it sits the monster who is always highly revered, most of all at the times of catching waterfowls in nests ... This idol is so notorious that people come from distant villages to perform atrocious sacrifice to it – offering cattle, mainly horses; and they are certain that it (the idol) is the bearer of many goods, mainly ensuring the richness of waterfowls ...

Comparisons of different Yugran traditions indicate that the goose was one of the shapes or appearances of the most popular god of the "World Surveyor Man", and that Belogorye is still sometimes referred to as his home. Novitsky also describes a site for worshipping this "World Surveyor" or "Ob Master":

The home of the Ob Master was presumably near the stronghold Samarovo in the mouth of the river Irtysh. According to their heathen belief he was the god of the fish, depicted in a most impudent manner: a board of wood, nose like a tin tube, eyes of glass, little horns on top of the head, covered with rags, attired in a (gilt breasted) purple robe. Arms – bows, arrows, spears, armour, etc – were laid beside him. According to their heathen belief they say about the collected arms that he often has to fight in the water and conquer other vassals. The frenzy ones thought that the atrocious monster is especially horrifying in the darkness and in the large waters, that he comes through all the depths where he watches over all fish and aquatic animals and gives everyone as much as he pleases.—Novitsky: 59.

Modern history

The Christianization of the Mansi en masse started at the beginning of the 18th century. Grigory Novitsky describes the Christianization of the Pelym Mansi in 1714 and the Konda Mansi in 1715. The words of the village elder and the caretaker of the sanctuary, Nahratch Yeplayev, have been recorded:

We all know why you have come here – you want to pervert us from our ancient beliefs with your smooth-tongued flattery and damage and destroy our revered helper, but it is all in vain for you may take our heads but this we will not let you do.—Novitsky: 92–93

Novitsky describes the above-mentioned idol as follows:

The idol was carved of wood, attired in green clothes, the evil looking face was covered with white iron, a black fox skin was placed on its head; the whole sanctuary, especially his site which was higher than anywhere else, was decorated with purple broadcloth. Other smaller idols nearby which were placed lower were called the servants of the real idol. I think there were many other things in front of him – caftans, squirrel skins, etc.—Novitsky: 93

It seems that a compromise was reached whereby the idols would be saved – for now at least – and at last Nahratsh who had consulted the elders of the village proposed a compromise:

We will now obey the ruler's regulations and ukase. So we will not discard your teaching, we only beg you not to reject the idol so revered by our fathers and grandfathers, and if you wish to christen us, honour also our idol, christen it in a more honourable manner – with a golden cross. Then we will decorate and build a church with all the icons ourselves, as a custom goes, and we will place ours also among these.—Novitsky: 94–95

This arrangement seems to have lasted for a while, but later it is recorded that this agreement was broken and the totems and idols so sacred to the Mansi and Khanty were burned by Russian Christian zealots.[citation needed] Many of these totems were not destroyed, but hidden, their locations kept secret over the generations. Even during repression of the 1930s many of these sacred sites remained undiscovered by the authorities and some can be found today.[citation needed]

Yugrian principalities and relations with the Tatars and Russians

This section does not cite any external source. HandWiki requires at least one external source. See citing external sources. (July 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

There are three or four known proto-states of the Yugran inhabitants, both Khanty and Mansi. The Principality of Pelym was located in the basin of the Konda river and stretched from the mouth of the Sosva River near Tavda up to Tabory. The stronghold of the Pelym princes was also a significant religious centre; a sacred Siberian larch grew in its surroundings and even in the 18th century people used to hang the skins of sacrificed horses on its branches. Near the sacred tree was a worship storehouse with five idols of human figure, and smaller storehouses with high pillars and human-faced peaks around it for storing sacrificial instruments. The bones of sacrificial animals were stored in a separate building (Novitski: 81).

The Principality of Konda (mainly Mansi) formed a large semi autonomous part of the Pelym principality, according to the tax registers from 1628/1629 it was inhabited by 257 tax-paying Mansi. The treasures of Prince Agai of Konda who was imprisoned by the Russians in 1594 gives us a good picture of the wealth of the Yugran nobles of this period. Namely, the Russians confiscated two silver crowns, a silver spoon, a silver beaker, a silver spiral bracelet, "precious drapery" and numerous pelts and precious furs (Bahrushin 1955, 2:146). The third part of the Pelym principality was the region of Tabary, in which inhabited 102 adults in 1628/1629. Preceding the coming of the Russians, the Mansi of this region were farmers and according to the tradition Yermak collected tribute in the form of grain (Bahrushin 1955, 2:147).

It is believed the Yugran people or Ob-Ugrians had made trade with many countries far and wide since the earliest times. This trade was described in journals attributed to Abu Hamid al-Gharnati the Arab traveller during the 12th century:

And from Bolghar merchants travel to the land of heathens, called Wisu; marvellous beaver skins come from there, and they take there wedge-shaped unpolished swords made in Azerbaijan in their turn… But the inhabitants of Visu take these swords to the land that lies near the Darkness [Yugra] by the Black Sea [now known as the White Sea], and they trade the swords for sable skins. And these people take the swords and cast them into the Black Sea; but Allah the Almighty sends them a fish which size is like a mountain [a whale]; and they sail out to the fish in their ships and carve its flesh for months on end.—Bahrushin 1955, 2: 58–59

According to some sources, Novgorod launched military campaigns against the Yugrans "living with the Samoyeds in the Land of Midnight" already at the end of the first millennium (Bahrushin 1955,1:86). At that time, the Russians probably came into contact with the Mansi who were still living in Europe, along the upper course of the river Pechora, in the neighbourhood of the ancient Komi realm of Great Perm. The Novgorod Chronicle tells of a military campaign under the leadership of Yadrei of Novgorod in 1193, which ended in the destruction of the Novgorod forces. The defeat was blamed on some Novgorodans who had reportedly "been in contact with the Yugrans" (Bahrushin 1955, 1:75).

From the 13th to 15th centuries, Yugra was supposed to pay tribute to Novgorod. But taxes could be collected only by means of armed forces. The chronicles describe several campaigns, mentioning the strong resistance of Yugran princes who took shelter in their strongholds. After the annexation of Ustyug by Moscow in the 14th century, Muscovite campaigns began instead of the Novgorodan ones.

In the 15th century, the most important Russian stronghold in Permland and the starting point for all expeditions going to the East was the diocese established on the Vym River by Stephan of Perm. In 1455, the Mansi of Pelym launched a campaign under the command of Prince Asyka. Moscow reciprocated by forming an alliance with Prince Vasily of Great Perm who together with the warriors of Vym who took part in the 1465 expedition to Yugra (Bahrushin 1955, 1:76). It is recorded in the Russian Chronicles that, in 1465, as a result of this raid, two minor "Yugrian" princes (Kalpik and Chepik) were compelled to submit to the Russians and pay tribute. They were soon deposed. In 1467, during a second campaign, Prince Asyka himself was captured and brought to Vyatka (Bahrushin 1955,2:113). In 1483, Moscow sent forth another expedition against the princes of Yugra and Konda where the "grand duke" Moldan was captured (Bahrushin 1955, 2:113). In 1499, Moscow dispatched a great force against "Yugra" (Pelym; led by Prince Semyon Kurbski), Konda or Koda (led by Prince Pyotr Ushatyi), and the "Gogulichi", the free Voguls or Mansi). The 4,000-strong army, using dog and reindeer teams, reached the Lyapin stronghold of the Khanty, located on the river of the same name (Bahrushin 1955, 1:76–77). In the source it is told that 40 strongholds were taken and 58 Khanty and Mansi princes captured in the expedition. At the end of the 15th century the Grand Duke of Moscow assumed the honorary title of Prince of Yugra. By the 16th century, several Yugran princes were paying tribute to the Siberia Khanate and participated in their military ventures against Russian settlers protected by Cossacks and Komi auxiliaries who were chasing the Yugran natives from their homes.

In response, the Khanty and Mansi of Pelym continually sent forth counter-campaigns to the lands of Great Perm. Thus, the year 1581 went into history as the year of the raiding of Kaigorod and Cherdyn. According to Russian estimates, the army of the Mansi and their allies, the Tatars, stood 700 strong (Bahrushin 1955, 1:99; 2:144). Continuing resistance to border conflagration led to the launching of a campaign in 1582–1584 arranged and financed by the Stroganovs and led by the Cossack leader Yermak Timofeyevich, which began with the destruction of a Mansi war band that had invaded the Russian settlers territory and ended as a punitive expedition against the Pelym Mansi and their ally the Siberian Khan. In some sources, Alach, Prince of Koda figures as an important ally of the Siberian Khan Kuchum Khan and is said to have been awarded one of the Yermak mail-coats taken from the enemy (Bahrushin 1955, 1:114).

In 1592, another Russian campaign against the Mansi of Pelym was launched. It ended in 1593 when the stronghold of Prince Ablegirim of Pelym was taken, the prince and his family captured and a Russian fortress erected in the heart of the stronghold. Although in the following year the Pelym principality suffered the loss of its lands lying on the Konda River, the Mansi did not give up resistance. In 1599, they once again brought "war, theft and treachery" to the banks of the Chusovaya River and Kurya River and plundered the Russian settlements there (Bahrushin, 2:143–144).

The close connections between the Yugrans and the Turkic Tartars are also demonstrated by the fact that even in the 1660s, the idea of restoring the Kuchum Khanate was still popular with the Khanty of Beryozovo (Bahrushin, 2:143–144). It was only in the middle of the 17th century that Moscow succeeded in subduing Yugra.

In the 18th century, the successors of the Principality of Pelym and Principality of Konda – princes Vassili and Fyodor – lived in Pelym. They became Russianized and performed various duties for the Tsarist government. The Mansi, however, considered them still as their rulers. The fact that the ancient family of princes ruled on in Konda is also proved by a tsar letter from 1624:

He, prince Vassili and prince Fyodor have close brothers in Big Konda – our tax-paying murzas, and our simple Voguls are ruled by them in Big Konda, the brothers of prince Vasily, the murzas." (Bahrushin 1955, 2: 148)

Prince Vassili and Prince Fyodor have close brothers in Big Konda – our tax-paying murzas, and our simple Voguls are ruled by them in Big Konda, the brothers of Prince Kyntsha of Konda received a deed of gift from the Tsar in 1680 which confirmed his noble position. Even in the 18th century, the Konda princes were known for their relative independence. It is assumed that, as late as 1715, Prince Satyga of Konda and his 600 armed men made an attempt to impede the Christianisation of the Konda Mansi (Novitski: 98). From 1732–1747, Konda was ruled by Satyga's son Prince Osip Grigoryev, followed by his own son Prince Vlas Ossipov. According to recent research by Aado Lintrop, one of the great-grandchildren of Satyga, the teacher of the Turinsky community school, Aleksander Satygin claimed the title "Prince of Konda" as late as 1842.

Hungarian Urheimat

Yugra and its vicinity to the south are considered to be the place of origin of the Hungarians (in Hungarian magyar őshaza). One hypothesis says that the name Hungary is a variety of the name Yugra (the Hungarians also were known in several languages under the name of Ugri, and are still known under this name in Ukrainian).

The Hungarian language is the closest linguistic relative of Khanty and Mansi. It is believed that Hungarians moved westwards from Yugra (present-day Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug), first settling on the western side of the Urals, in the region known as Magna Hungaria (Great Yugria). Then they moved to the region of Levédia (present-day Eastern Ukraine), then to the region of Etelköz (present-day Western Ukraine), finally reaching the Carpathian Basin (present-day Hungary) in the 9th century.[11][12]

See also

- Name of Hungary

- Ugrians

References

- ↑ Naumov 2006, p. 53, The Russians named it Yugorskaia Zemlitsa (Yugor Land or Yugra).

- ↑ Honti, László (1979). "Characteristic Features of Ugric Languages (observations on the Question of Ugric Unity)". Acta Linguistica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 29 (1/2): 1–26. ISSN 0001-5946. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44309976.

- ↑ Vásáry, István (1982). "The 'Yugria' Problem". in Róna-Tas, András. Chuvash studies. Bibliotheca orientalis hungarica. Budapest: Akadémiai kiadó. ISBN 978-963-05-2851-1.

- ↑ Rasputin, Valentin (29 October 1997) (in en). Siberia, Siberia. Northwestern University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8101-1575-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=fzchffZ3BFQC.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Naumov 2006, p. 53.

- ↑ Martin, Janet (7 June 2004) (in en). Treasure of the Land of Darkness: The Fur Trade and Its Significance for Medieval Russia. Cambridge University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-521-54811-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=z0tet2-BeXcC.

- ↑ Naumov 2006, pp. 53, After Novgorod had been annexed by the newly emerging centralized Russian state in 1478, its government, located in Moscow, tried to lay claim to Yugor Land as well... In 1483 Prince Ivan III sent a large expeditionary force to Siberia... In 1499–1500 Ivan III sent another large force.

- ↑ Naumov 2006, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ See Karjalainen 1918:243–245, Shestalov 1987:347.)

- ↑ (Novitski: 61).

- ↑ Sudár (2015). Magyarok a honfoglalás korában. pp. 152.

- ↑ Sudár (2015). Magyarok a honfoglalás korában. pp. 153.

Sources

- Bakhrushin 1955, 1 = Bakhrushin S. B. Puti v Sibir v XVI-XVII vv. Nautshnyje trudy III. Izbrannyje raboty po istorii Sibiri XVI-XVII vv. Tshast pervaja. Voprosy russkoi kolonizatsii Sibiri v XVI-XVII vv. Moscow 1955, ss. 72–136.

- Bakhrushin 1955, 2 = Bakhrushin S. B. Ostjatskyje i vogulskije knjazhestva v XVI i XVII vv. Nautshnyje trudy III. Izbrannyje raboty po istorii Sibiri XVI-XVII vv. Tshast vtoraja. Istorija narodov Sibiri v XVI-XVII vv. Moscow 1955, ss. 86–152.

- Al Garnati = Puteshestvije Abu Hamida al-Garnati v Vostotshnuju I Tsentralnuju Jevropu. Moscow 1971.

- Naumov, Igor V. (22 November 2006) (in en). The History of Siberia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-20703-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=4498YjPq6mgC.

- Pieksämäki, The Great Bear = The Great Bear. A Thematic Anthology of Oral Poetry in the Finno-Ugrian Languages. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seuran Toimituksia 533. 1993.

- Karjalainen 1918 = Karjalainen, K. F. Jugralaisten usonto. Suomen suvun uskonnot III. Porvoo.

- Karjalainen 1922 = Karjalainen, K. F. Die Religion der Jugra-Vöaut;lker II. FF Communications 44. Porvoo.

- Novitsky = Novitskij G. Kratkoe opisanie o narode ostjackom. Studia uralo-altaica III. Szeged 1973.

- Shestalov 1987 = Shestalov J. Taina Sorni-nai. Moscow.

- Shestalova-Fidorovitsh 1992 = Svjashtshennyi skaz o sotvorenii zemli. Mansiiskie mify. Perevod O. Shestalovoi-Fidorovitsh. Saint Petersburg, Khanty-Mansiysk.

- Sokolova 1983 = Sokolova Z. P. Sotsialnaja organizatsija khantov i mansi v XVIII-XIX vv. Problemy fratrii i roda. Moscow.

- Aado Lintrop, The Mansi, History and Present Day (1977)

- Endangered Uralic Peoples, RAIPON (Russian Association of Indigenous Peoples of the North) – sourced at hunmagyar.org

- Sudár, Balázs (2015) (in Hungarian). Magyarok a honfoglalás korában. Helikon. ISBN 978-963-227-592-5.

|