Social:Mansi language

| Mansi | |

|---|---|

| ма̄ньси ла̄тыӈ | |

| Pronunciation | [maːnʲɕi laːtəŋ] |

| Native to | Russia |

| Region | Khanty–Mansi |

| Ethnicity | 12,200 Mansi (2020 census)[1] |

Native speakers | 2,200 (2020 census)[1] |

Uralic

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | mns |

| Glottolog | mans1269[2] |

Map of regions where those who speak the extant Northern Mansi and Eastern Mansi languages. The gradient represents the uncertainty in where these languages can be spoken. (2022) | |

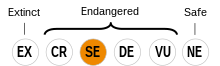

Northern Mansi is classified as Severely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger (2010) | |

The Mansi languages are spoken by the Mansi people in Russia along the Ob River and its tributaries, in the Khanty–Mansi Autonomous Okrug, and Sverdlovsk Oblast. Traditionally considered a single language, they constitute a branch of the Uralic languages, often considered most closely related to neighbouring Khanty and then to Hungarian.

The base dialect of the Mansi literary language is the Sosva dialect, a representative of the northern language. The discussion below is based on the standard language. Fixed word order is typical in Mansi. Adverbials and participles play an important role in sentence construction. A written language was first published in 1868, and the current Cyrillic alphabet was devised in 1937.

Varieties

Mansi is subdivided into four main dialect groups which are to a large degree mutually unintelligible, and therefore best considered four languages. A primary split can be set up between the Southern variety and the remainder. A number of features are also shared between the Western and Eastern varieties, while certain later sound changes have diffused between Eastern and Northern (and are also found in some neighboring dialects of Northern Khanty to the east).

Individual dialects are known according to the rivers their speakers live(d) on:[3]

| Proto‑Mansi |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The sub-dialects given above are those which were still spoken in the late 19th and early 20th century and have been documented in linguistic sources on Mansi. Pre-scientific records from the 18th and early 19th centuries exist also of other varieties of Western and Southern Mansi, spoken further west: the Tagil, Tura and Chusovaya dialects of Southern[4] and the Vishera dialect of Western.[5]

The two dialects last mentioned were hence spoken on the western slopes of the Urals, where also several early Russian sources document Mansi settlements. Placename evidence has been used to suggest Mansi presence reaching still much further west in earlier times,[6] though this has been criticized as poorly substantiated.[7]

Northern Mansi has strong Russian, Komi, Nenets, and Northern Khanty influence, and it forms the base of the literary Mansi language. There is no accusative case; that is, both the nominative and accusative roles are unmarked on the noun. */æ/ and */æː/ have been backed to [a] and [aː].

Western Mansi became extinct ca. 2000. It had strong Russian and Komi influences; dialect differences were also considerable.[8] Long vowels were diphthongized.

Eastern Mansi is spoken by 100–200 people. It has Khanty and Siberian Tatar influence. There is vowel harmony, and for */æː/ it has [œː], frequently diphthongized.

Southern (Tavda) Mansi was recorded from area isolated from the other Mansi varieties. Around 1900 a couple hundred speakers existed; in the 1960s it was spoken only by a few elderly speakers,[8] and it has since then become extinct. It had strong Tatar influence and displayed several archaisms such as vowel harmony, retention of /y/ (elsewhere merged with */æ/), /tsʲ/ (elsewhere deaffricated to /sʲ/), /æː/ (elsewhere fronted to /aː/ or diphthongized) and /ɑː/ (elsewhere raised to /oː/).

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | (Alveolo-) Palatal |

Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plain | Labialized | ||||

| Nasals | /m/ м |

/n/ н |

/nʲ/ нь |

/ŋ/ ӈ |

/ŋʷ/ ӈв |

| Stops | /p/ п |

/t/ т |

/tʲ/ ть |

/k/ к |

/kʷ/ кв |

| Affricate | /ɕ/ [1] ~ /sʲ/ щ ~ сь |

||||

| Fricatives | /s/ с |

/x/ [2] /ɣ/ х г |

/xʷ/ [3] *ɣʷ [4] хв (в) | ||

| Semivowels | /j/ й |

/w/ в | |||

| Laterals | /l/ л |

/lʲ/ ль |

|||

| Trill | /r/ р |

||||

The inventory presented here is a maximal collection of segments found across the Mansi varieties. Some remarks:

- /ɕ/ is an allophone of /sʲ/.[10]

- The voiceless velar fricatives /x/, /xʷ/ are only found in the Northern group and the Lower Konda dialect of the Eastern group, resulting from spirantization of *k, *kʷ adjacent to original back vowels.

- According to Honti, a contrast between *w and *ɣʷ can be reconstructed, but this does not surface in any of the attested varieties.

- The labialization contrast among the velars dates back to Proto-Mansi, but was in several varieties strengthened by labialization of velars adjacent to rounded vowels. In particular, Proto-Mansi *yK → Core Mansi *æKʷ (a form of transphonologization).

Vowels

The vowel systems across Mansi show great variety. As typical across the Uralic languages, many more vowel distinctions were possible in the initial, stressed syllable than in unstressed ones. Up to 18–19 stressed vowel contrasts may be found in the Western and Eastern dialects, while Northern Mansi has a much reduced, largely symmetric system of 8 vowels, though lacking short **/e/ and having a very rare long [iː]:

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Remarks:

- ы/и /i/ has a velar allophone [ɨ] before г /ɣ/ and after х /x/.[11]

- Long [iː] occurs as a rare and archaic phonetic variant of /eː/, cf. э̄ти ~ ӣти (‘in the evening, evenings’)[12]

- Long /eː/ and /oː/ can be pronounced as diphthongs [e͜ɛ] and [o͜ɔ].[11]

- у /u/ is found in unstressed (“non-first”) syllables before в /w/, in the infinitive suffix -ункве /uŋkʷe/ and in obscured compound words.[11]

- Reduced /ə/ becomes labialized [ə̹] or [ɞ̯] before bilabial consonants м /m/ and п /p/.[11]

Alphabet

The first publication of the written Mansi language was a translation of the Gospel of Matthew published in London in 1868.[13] In 1932 a version of Latin alphabet was introduced by the Institute of the Peoples of the North with little success.

The former Latin alphabet:

In 1937, Cyrillic replaced the Latin.

The highlighted letters, and Г with the value /ɡ/, are used only in names and loanwords. The allophones /ɕ/ and /sʲ/ are written with the letter Щ or the digraph СЬ respectively.

| А /a/ |

А̄ /aː/ |

Б /b/ |

В /◌ʷ/ |

Г /ɡ/, /ɣ/ |

Д /d/ |

Е /ʲe/ |

Е̄ /ʲe:/ |

Ё /ʲo/ |

Ё̄ /ʲo:/ |

Ж /ʒ/ |

З /z/ |

И /i/ |

Ӣ /i:/ |

Й /j/ |

К /k/ |

Л /l/, /ʎ/ |

М /m/ |

Н /n/, /ɲ/ |

Ӈ /ŋ/ |

О /o/ |

О̄ /o:/ |

| П /p/ |

Р /r/ |

С /s/ |

Т /t/ |

У /u/ |

Ӯ /uː/ |

Ф /f/ |

Х /χ/ |

Ц /t͡s/ |

Ч /t͡ʃʲ/ |

Ш /ʃ/ |

Щ /ʃʲtʃʲ/ |

Ъ /-/ |

Ы /ɪ/ |

Ы̄ /ɪ:/ |

Ь /◌ʲ/ |

Э /ə~ɤ/ |

Э̄ /ə:~ɤ:/ |

Ю /ʲu/ |

Ю̄ /ʲu:/ |

Я /ʲa/ |

Я̄ /ʲa:/ |

Grammar

Mansi is an agglutinating, subject–object–verb (SOV) language.[14]

Article

One way to express a noun's definiteness in a sentence is with articles, and Northern Mansi uses two articles. The Indefinite is derived from the demonstrative pronominal word ань ('now'), the definite is derived from the number аква/акв ('one'); ань ('the'), акв ('a/an'). They both are used before the defined word. And if their adverbial and numeral meanings are to be expressed; ань always stands before the verb or a word with a similar function and is usually stressed, акв behaves the same and is always stressed.[15]

- Definiteness (determination) can also be expressed by the third (less often second) person singular possession marker,[16] or in case of direct objects, using transitive conjugation.[17] E.g. а̄мп (’dog’) → а̄мпе (’his/her/its dog’, ’the dog’); ха̄п (’boat’) → ха̄п на̄лув-нарыгтас (’he/she pushed a boat in the water’) ≠ ха̄п на̄лув-нарыгтастэ (’he/she pushed the boat in the water’).

Nouns

There is no grammatical gender. Mansi distinguishes between singular, dual and plural number. Six grammatical cases exist. Possession is expressed using possessive suffixes, for example -ум, which means "my".

Grammatical cases, declining

There are 5 ways the case suffix can change.

- If the word last letter is a consonant:

Example with: пӯт /puːt/ (cauldron) [18] case sing. dual plural nom. пӯт

puːtпӯтыг

puːtɪɣпӯтыт

puːtətloc. пӯтт

puːttпӯтыгт

puːtɪɣtпӯтытт

puːtəttlat. пӯтн

puːtnпӯтыгн

puːtɪɣnпӯтытн

puːtətnabl. пӯтныл

puːtnəlпӯтыгныл

puːtɪɣnəlпӯтытныл

puːtətnəltrans. пӯтыг

puːtɪɣ- - instr. пӯтыл

puːtəlпӯтыгтыл

puːtɪɣtəlпӯтытыл

puːtətəl

- If the word's last letter is a vowel:

Example with: э̄ква /eːkʷa/ (wife, older woman) case sing. dual plural nom. э̄ква

eːkʷaэ̄кваг

eːkʷaɣэ̄кват

eːkʷatloc. э̄кват

eːkʷatэ̄квагт

eːkʷaɣtэ̄кватт

eːkʷattlat. э̄кван

eːkʷanэ̄квагн

eːkʷaɣnэ̄кватн

eːkʷatnabl. э̄кваныл

eːkʷanəlэ̄квагныл

eːkʷaɣnəlэ̄кватныл

eːkʷatnəltrans. э̄кваг

eːkʷaɣ- - instr. э̄квал

eːkʷalэ̄квагтыл

eːkʷaɣtəlэ̄кватыл

eːkʷatəl

- If the word has a vowel (ы, и) as the last letter, it can be -йи- or just -и- :

Example with: са̄лы /saːli/ (deer) case sing. dual plural nom. са̄лы

saːliса̄лыйиг

saːlijiɣса̄лыт

eːkʷatloc. са̄лыт

saːlitса̄лыйигт

saːlijiɣtса̄лытт

saːlittlat. са̄лын

saːlinса̄лыйигн

saːlijiɣnса̄лытн

saːlitnabl. са̄лыныл

saːlinəlса̄лыйигныл

saːlijiɣnəlса̄лытныл

saːlitnəltrans. са̄лыйиг

saːlijiɣ- - instr. са̄лыл

saːlilса̄лыйигтыл

saːlijiɣtəlса̄лытыл

saːlitəl

- If the word's last letter is a palatalized consonant:

Example with: ща̄нь /ɕaːnʲ/ (mother) case sing. dual plural nom. ща̄нь

ɕaːnʲща̄ньыг

ɕaːnʲɪɣща̄ньыт

ɕaːnʲətloc. ща̄ньт

ɕaːnʲtща̄ньыгт

ɕaːnʲɪɣtща̄ньытт

ɕaːnʲəttlat. ща̄ньн

ɕaːnʲnща̄ньыгн

ɕaːnʲɪɣnща̄ньытн

ɕaːnʲətnabl. ща̄ньныл

ɕaːnʲnəlща̄ньыгныл

ɕaːnʲɪɣnəlща̄ньытныл

ɕaːnʲətnəltrans. ща̄ниг

ɕaːnʲiɣ- - instr. ща̄нил

ɕaːnʲilща̄ньыгтыл

ɕaːnʲɪɣtəlща̄ньытыл

ɕaːnʲətəl

- If the word has a syncopating stem:

Example with: сасыг /sasɪɣ/ (uncle) case sing. dual plural nom. сасыг

sasɪɣсасгыг

sasɣɪɣсасгыт

sasɣətloc. сасыгт

sasɪɣtсасгыгт

sasɣɪɣtсасгытт

sasɣəttlat. сасыгн

sasɪɣnсасгыгн

sasɣɪɣnсасгытн

sasɣətnabl. сасыгныл

sasɪɣnəlсасгыгныл

sasɣɪɣnəlсасгытныл

sasɣətnəltrans. сасгыг

sasɣɪɣ- - instr. сасгыл

sasɣəlсасгыгтыл

sasɣɪɣtəlсасгытыл

sasɣətəl

Missing cases can be expressed using postpositions, such as халныл (χalnəl, 'of, out of'), саит (sait, 'after, behind'), etc.

Possession

Possession is expressed with possessive suffixes, and the suffix change is determined by the last letter of a word. There are 5 ways that the suffixes can change:

- If the word has a consonant as the last letter:

Example with: пӯт /puːt/ (cauldron) possessor single double multiple 1st person sing. пӯтум

puːtɞ̯mпӯтагум

puːtaɣɞ̯mпӯтанум

puːtanɞ̯m2nd person sing. пӯтын

puːtənпӯтагын

puːtaɣənпӯтан

puːtan3rd person sing. пӯтэ

puːteпӯтаге

puːtaɣeпӯтанэ

puːtane1st person dual пӯтме̄н

puːtmeːnпӯтагаме̄н

puːtaɣameːnпӯтанаме̄н

puːtanameːn2nd person dual пӯты̄н

puːtiːnпӯтагы̄н

puːtaɣiːnпӯтаны̄н

puːtaniːn3rd person dual пӯтэ̄

puːteːпӯтаге̄н

puːtaɣeːпӯтанэ̄н

puːtaneː1st person plu. пӯтув

puːtuwпӯтагув

puːtaɣuwпӯтанув

puːtanuw2nd person plu. пӯты̄н

puːtiːnпӯтагы̄н

puːtaɣiːnпӯтаны̄н

puːtaniːn3rd person plu. пӯтаныл

puːtanəlпӯтага̄ныл

puːtanəlпӯта̄ныл

puːtanəl

- If the word has a vowel as the last letter:

Example with: э̄ква /eːkʷa/ (wife, older woman) possessor single double multiple 1st person sing. э̄квам

eːkʷamэ̄квагум

eːkʷaɣɞ̯mэ̄кванум

eːkʷanɞ̯m2nd person sing. э̄кван

eːkʷanэ̄квагын

eːkʷaɣənэ̄кван

eːkʷan3rd person sing. э̄кватэ

eːkʷateэ̄кваге

eːkʷaɣeэ̄кванэ

eːkʷane1st person dual э̄кваме̄н

eːkʷameːnэ̄квагаме̄н

eːkʷaɣameːnэ̄кванаме̄н

eːkʷanameːn2nd person dual э̄кван

eːkʷanэ̄квагы̄н

eːkʷaɣiːnэ̄кваны̄н

eːkʷaniːn3rd person dual э̄кватэ̄н

eːkʷateːnэ̄кваге̄н

eːkʷaɣeːэ̄кванэ̄н

eːkʷaneː1st person plu. э̄квав

eːkʷawэ̄квагув

eːkʷaɣuwэ̄кванув

eːkʷanuw2nd person plu. э̄кван

eːkʷanэ̄квагы̄н

eːkʷaɣiːnэ̄кваны̄н

eːkʷaniːn3rd person plu. э̄кваныл

eːkʷanəlэ̄кваганыл

eːkʷanəlэ̄квананыл

eːkʷanəl

- If the word has a vowel (ы, и) as the last letter:

Example with: са̄лы /saːli/ (deer) possessor single double multiple 1st person sing. са̄лым

saːlimса̄лыягум

saːlijaɣɞ̯mса̄лыянум

saːlijanɞ̯m2nd person sing. са̄лын

saːlinса̄лыягын

saːlijaɣənса̄лыян

saːlijan3rd person sing. са̄лытэ

saːliteса̄лыяге

saːlijaɣeса̄лыянэ

saːlijane1st person dual са̄лыме̄н

saːlimeːnса̄лыягаме̄н

saːlijaɣameːnса̄лыянаме̄н

saːlijanameːn2nd person dual са̄лын

saːlinса̄лыягы̄н

saːlijaɣiːnса̄лыяны̄н

saːlijaniːn3rd person dual са̄лытэ̄н

saːliteːса̄лыяге̄н

saːlijaɣeːса̄лыянэ̄н

saːlijaneː1st person plu. са̄лыюв

saːlijuwса̄лыягув

saːlijaɣuwса̄лыянув

saːlijanuw2nd person plu. са̄лын

saːlinса̄лыягы̄н

saːlijaɣiːnса̄лыяны̄н

saːlijaniːn3rd person plu. са̄лыяныл

saːlijanəlса̄лыяганыл

saːlijaɣanəlса̄лыянаныл

saːlijananəl

- If the word has a palatalized consonant as the last letter:

Example with: ща̄нь /ɕaːnʲ/ (mother) possessor single double multiple 1st person sing. ща̄нюм

ɕaːnʲɞ̯mща̄нягум

ɕaːnʲaɣɞ̯mща̄нянум

ɕaːnʲanɞ̯m2nd person sing. ща̄нин

ɕaːnʲənща̄нягын

ɕaːnʲaɣənща̄нян

ɕaːnʲan3rd person sing. ща̄не

ɕaːnʲeща̄няге

ɕaːnʲaɣeща̄нянэ

ɕaːnʲane1st person dual ща̄няме̄н

ɕaːnʲameːnща̄нягаме̄н

ɕaːnʲaɣameːnща̄нянаме̄н

ɕaːnʲanameːn2nd person dual ща̄нӣн

ɕaːnʲiːnща̄нягы̄н

ɕaːnʲaɣiːnща̄няны̄н

ɕaːnʲaniːn3rd person dual ща̄не̄

ɕaːnʲeːща̄няге̄н

ɕaːnʲaɣeːща̄нянэ̄н

ɕaːnʲaneː1st person plu. ща̄нюв

ɕaːnʲuwща̄нягув

ɕaːnʲaɣuwща̄нянув

ɕaːnʲanuw2nd person plu. ща̄нӣн

ɕaːnʲiːnща̄нягы̄н

ɕaːnʲaɣiːnща̄няны̄н

ɕaːnʲaniːn3rd person plu. ща̄няныл

ɕaːnʲanəlща̄няга̄ныл

ɕaːnʲanəlща̄ня̄ныл

ɕaːnʲanəl

- If the word has syncopating stem:

Example with: сасыг /sasɪɣ/ (uncle) possessor single double multiple 1st person sing. сасгум

sasɣɞ̯mсасгагум

sasɣaɣɞ̯mсасганум

sasɣanɞ̯m2nd person sing. сасгын

sasɣənсасгагын

sasɣaɣənсасган

sasɣan3rd person sing. сасгэ

sasɣeсасгаге

sasɣaɣeсасганэ

sasɣane1st person dual сасыгме̄н

sasɪɣmeːnсасгагаме̄н

sasɣaɣameːnсасганаме̄н

sasɣanameːn2nd person dual сасгы̄н

sasɣiːnсасгагы̄н

sasɣaɣiːnсасганы̄н

sasɣaniːn3rd person dual сасгэ̄

sasɣeːсасгаге̄н

sasɣaɣeːсасганэ̄н

sasɣaneː1st person plu. сасгув

sasɣuwсасгагув

sasɣaɣuwсасганув

sasɣanuw2nd person plu. сасгы̄н

sasɣiːnсасгагы̄н

sasɣaɣiːnсасганы̄н

sasɣaniːn3rd person plu. сасганыл

sasɣanəlсасгага̄ныл

sasɣaɣaːnəlсасга̄ныл

sasɣanəl

Verbs

Mansi conjugation has three persons, three numbers, two tenses, and five moods. Active and passive voices exist.

There is no clear distinction between transitive and intransitive verbs.[19]

The verb can conjugate in a Definite and Indefinite way which depends on if the sentence has an object, which the action depicted by the verb refers to directly.

Personal suffixes

Personal suffixes are attached after the verbal marker. The suffixes are the following:

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -ум | -ме̄н | -в |

| 2nd person | -ын | -ы̄н | -ы̄н |

| 3rd person | -ø | -ø | -ыт |

Tenses

Tenses are formed with suffixes except for the future.

Present tense

The tense suffix precedes the personal suffix. The form of the present tense suffix depends on the character of the verbal stem, as well as moods. Tense conjugation is formed with the suffixes -эг, -э̄г, -и, -э, -э̄, -г, or -в.[20] In the following examples, the tense suffix is in bold and the personal ending is in italic.

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | рӯпитэ̄гум | рӯпитыме̄н | рӯпитэ̄в |

| 2nd person | рӯпитэ̄гын | рӯпитэгы̄н | рӯпитэгы̄н |

| 3rd person | рӯпиты | рӯпитэ̄г | рӯпитэ̄гыт |

The present tense suffix -э̄г is used if the following personal marker contains a consonant or a highly reduced vowel; the suffix -эг is used if the following personal marker has a stronger vowel, as it is the case in 2nd person dual and plural. 1st person dual has no tense marker but rather a ы between the verb stem and personal ending.

Verb stems that end in a vowel, have -г as verbal marker. Verb stems that end with the vowel у have -в as verbal marker.[21]

3rd person dual has no personal ending. If the verbal stem ends in a vowel, the tense suffix becomes -ыг.

1st person plural personal ending is -в if the verbal stems ends in a consonant; the personal ending becomes -ув if the verbal stem ends in a vowel.

Past tense

The past tense suffix if the verb stem is monosylabalic is -ыс- and if the verb is polysyllabic it is -ас-:

| Сяр ма̄ньлат каснэ хум Евгений Глызин о̄лыс. | The youngest participant in the competition was Jevgeni Glizin. |

| Ёська мо̄лхо̄тал урт рӯпитас. | Joseph worked at the mountain yesterday. |

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | рӯпитасум | рӯпитасаме̄н | рӯпитасув |

| 2nd person | рӯпитасын | рӯпитасы̄н | рӯпитасы̄н |

| 3rd person | рӯпитас | рӯпитасы̄г | рӯпита̄сыт |

3rd person dual in past tense has a -ы̄г personal ending.

The 1st person plural personal suffix turns into -ув.

Future "tense"

To represent the Future, the verb патуӈкве (not dissimilar to Hungarians use of the verb fogni) is used as an auxiliary verb conjugated in the Present Indicative:

| Тав кӯтювытыл рӯпитаӈкве паты. | He will work with (female) dogs. |

Definiteness

Verbs can conjugate two ways to show their agreement with the sentence's object.

Indefinite conjugation

In Indefinite verb conjugations there is no object present. It is not represented by any suffix.

Definite conjugation

In Definite verb conjugations there are three ways the verb can represent the direct object's number.

| Singular Object | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | рӯпитылум | рӯпитыламēн | рӯпитылув |

| 2nd person | рӯпитылын | рӯпитылы̄н | рӯпитылы̄н |

| 3rd person | рӯпитытэ | рӯпитытэ̄н | рӯпитыяныл |

The singular object is expressed with the -ыл- suffix which changes depending on the mood and tense.

| Dual Object | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | рӯпитыягум | рӯпитыягмēн | рӯпитыягув |

| 2nd person | рӯпитыягын | рӯпитыягы̄н | рӯпитыягы̄н |

| 3rd person | рӯпитыяге | рӯпитыягēн | рӯпитыяга̄ныл |

The dual object is expressed with the -ыяг- suffix which changes depending on the mood and tense.

| Plural Object | Singular | Dual | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | рӯпитыянум | рӯпитыянмēн | рӯпитыянув |

| 2nd person | рӯпитыянын or рӯпитыян |

рӯпитыяны̄н or рӯпитыян |

рӯпитыяны̄н or рӯпитыян |

| 3rd person | рӯпитыянэ | рӯпитыянанэ̄н or рӯпитыянэ̄н |

рӯпитыяна̄ныл or рӯпитыя̄ныл |

The plural object is expressed with the -ыян- suffix which changes depending on the mood and tense.

Moods

There are four moods: indicative, mirative, optative, imperative and conditional.

Indicative mood has no suffix. Imperative mood exists only in the second person. Optative and Imperative don't have tenses.

Mirative mood

Is a mood presented in the present indefinite by the -не suffix and by the -но in definite.

In the past tense it is represented by the -ам suffix, both in indefinite and definite.

Optative mood

The mood is represented by the -нӯв and -нув suffixes, determined by the vowel in the next suffix.

Imperative mood

It exists only in the second person, and in indefinite conjugation, it doesn't show any personal markers, and it is represented by the -эн and -э̄н suffixes.

Active/Passive voice

Verbs have active and passive voice. Active voice has no suffix; the suffix to express the passive is -ве-.

Verbal prefixes

Verbal prefixes are used to modify the meaning of the verb in both concrete and abstract ways. For example, with the prefix эл- (el-) (away, off) the verb мина (mina) (go) becomes элмина (elmina), which means to go away. This is surprisingly close to the Hungarian equivalents: el- (away) and menni (to go), where elmenni is to go away

ēl(a) – 'forwards, onwards, away'

| jōm- 'to go, to stride' | ēl-jōm- 'to go away/on' |

| tinal- 'to sell' | ēl-tinal- 'to sell off' |

χot – 'direction away from something and other nuances of action intensity'

| min- 'to go' | χot-min- 'to go away, to stop' |

| roχt- 'to be frightened' | χot-roχt- 'to take fright suddenly' |

Numbers[22]

Whole and below ten numbers

| # | Northern Sosva Mansi | Hungarian |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | аква (akʷa) | egy |

| 2 | китыг (kitɪɣ) | kettő |

| 3 | хурум (xuːrɞ̯m) | három |

| 4 | нила (nʲila) | négy |

| 5 | ат (at) | öt |

| 6 | хот (xoːt) | hat |

| 7 | са̄т / ма̄нь са̄т (saːt / maːnʲ saːt) | hét |

| 8 | нёлолов (nʲololow) | nyolc |

| 9 | онтолов (ontolow) | kilenc |

| 10 | лов (low) | tíz |

| 20 | хус (xus) | húsz |

| 100 | са̄т / яныг са̄т (saːt / janiɣ saːt) | száz |

| 1000 | со̄тыр (soːtər) | ezer |

Numbers 1 and 2 also have attributive forms: акв (1) and кит (2); compare with Hungarian két, Old Hungarian kit).

The ма̄нь and яныг before 7 and 100 are there to differentiate between the two if both are in the same number or sentence; meaning small and big respectively.

Numbers between twenty and ten

The Mansi numbering system is different in this range than after twenty.

Here, you form a number with the word хуйп (above, more than);

| # | Northern Sosva Mansi | Hungarian |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | аквхуйплов (akʷxujploβ) | tizenegy |

| 15 | атхуйплов (atxujploβ) | tizenöt |

| 19 | онтоловхуйплов (ontoloβxujploβ) | tizenkilenc |

There for, аквхуйплов means "one over/above ten", in a similar way to other Uralc languages.

Numbers above twenty

Number is this range use the word нупыл (towards);

| # | Northern Sosva Mansi | Hungarian |

|---|---|---|

| 21 | ва̄т нупыл аква (βaːt nupəl akʷa) | huszonegy |

| 31 | налыман нупыл аква (naliman nupəl akʷa) | harmincegy |

| 41 | атпан нупыл аква (atpan nupəl akʷa) | negyvenegy |

| 51 | хо̄тпан нупыл аква (xoːtpan nupəl akʷa) | ötvenegy |

| 61 | са̄тлов нупыл аква (saːtloβ nupəl akʷa) | hatvanegy |

| 71 | нёлса̄т нупыл аква (nʲolsaːt nupəl akʷa) | hetvenegy |

| 81 | онтырса̄т нупыл аква (ontərsaːt nupəl akʷa) | nyolcvanegy |

| 91 | са̄т нупыл аква (saːt nupəl akʷa) | kilencvenegy |

There for, ва̄т нупыл аква means "Twoards thirty with one".

Numbers above and beyond hunderd

You just add the number after the biggest number;

| # | Northern Sosva Mansi | Hungarian |

|---|---|---|

| 101 | са̄т аква (saːt akʷa) | százegy |

| 111 | са̄т аквхуйплов (saːt akʷxujploβ) | száztizenegy |

| 121 | са̄т ва̄т нупыл аква (saːt βaːt nupəl akʷa) | százhuszonegy |

| 201 | китса̄т аква (xoːtpan akʷa) | kétszázegy |

| 301 | хурумса̄т аква (xuːrɞ̯msaːt akʷa) | harmincegy |

Sample vocabulary

| Northern Mansi | English |

|---|---|

| Па̄ща о̄лэн | Hello (to one person) |

| Па̄ща о̄лэ̄н | Hello (to multiple people) |

| Наӈ наме ма̄ныр? | What is your name? |

| Ам намум ___. | My name is ____. |

| Пумасипа! | Thank you |

| О̄с ёмас ӯлум | Goodbye |

| нэ̄ | woman |

| хум | man, person |

| ня̄врам | child |

| юрт, рума | friend |

| а̄щ | father |

| ща̄нь | mother |

| пы̄г | boy |

| а̄ги | girl |

| кол | house |

| ӯс | city |

| ма̄ | land |

| ха̄ль | birch tree |

| я̄ | river |

| во̄р | forest |

| тӯр | lake |

| нэ̄пак | book |

| пасан | table |

| а̄мп | dog |

| кати | cat |

| ӯй | animal |

| во̄рто̄лнут | bear |

| хӯл | fish |

Examples

| Northern Mansi | English | Morphological translation |

|---|---|---|

| Aм хӯл алысьлаӈкве минасум. | I went fishing. | I fish hunt.to go.did.I |

| А̄кврись, а̄кврись, тутсяӈын хо̄т? — А̄мпын тотвес. |

Dear auntie, dear auntie, where is your sewing kit? — It has been taken by the dog. |

Auntie.dear, auntie.dear, sewing-kit.your where? — Dog.by taken.was.(it). |

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Итоги Всероссийской переписи населения 2020 года. Таблица 6. Население по родному языку.". https://rosstat.gov.ru/vpn_popul.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Mansic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/mans1269.

- ↑ Honti 1998, pp. 327–328.

- ↑ Gulya, Janos (1958). "Egy 1736-ból származó manysi nyelvemlék". Nyelvtudományi Közlemények (60): 41–45.

- ↑ Kannisto, Artturi (1918). "Ein Wörterverzeichnis eines ausgestorbenen wogulischen Dialektes in den Papieren M. A. Castréns". Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Aikakauskira (30/8).

- ↑ Kannisto, Artturi (1927). "Über die früheren Wohngebiete der Wogulen". Finnisch-Ugrische Forschungen (XVIII): 57–89.

- ↑ Napolskikh, Vladimir V. (2002). ""Ugro-Samoyeds" in Eastern Europe?". Finnisch-Ugrische Mitteilungen (24/25): 127–148.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kálmán 1965, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Honti 1998, p. 335.

- ↑ Rombandeeva, E. I.; Ромбандеева, Е. И. (2017). Sovremennyĭ mansiĭskiĭ i︠a︡zyk : leksika, fonetika, grafika, orfografii︠a︡, morfologii︠a︡, slovoobrazovanie. Obsko-ugorskiĭ institut prikladnykh issledovaniĭ i razrabotok, Обско-угорский институт прикладных исследований и разработок. Ti︠u︡menʹ. pp. 29. ISBN 978-5-6040210-8-8. OCLC 1062352461. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1062352461.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Kálmán 1989, pp. 32.

- ↑ Kálmán 1989, pp. 32, 99, 102.

- ↑ Rombandeeva, E. I.; Ромбандеева, Е. И. (2017). Sovremennyĭ mansiĭskiĭ i︠a︡zyk : leksika, fonetika, grafika, orfografii︠a︡, morfologii︠a︡, slovoobrazovanie. Obsko-ugorskiĭ institut prikladnykh issledovaniĭ i razrabotok, Обско-угорский институт прикладных исследований и разработок. Ti︠u︡menʹ. pp. 41. ISBN 978-5-6040210-8-8. OCLC 1062352461. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1062352461.

- ↑ Grenoble, Lenore A (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Springer. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4020-1298-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=qaSdffgD9t4C&q=Komi+word+order&pg=PA14.

- ↑ Rombandeeva, E. I.; Ромбандеева, Е. И. (2017). Sovremennyĭ mansiĭskiĭ i︠a︡zyk : leksika, fonetika, grafika, orfografii︠a︡, morfologii︠a︡, slovoobrazovanie. Obsko-ugorskiĭ institut prikladnykh issledovaniĭ i razrabotok, Обско-угорский институт прикладных исследований и разработок. Ti︠u︡menʹ. pp. 188. ISBN 978-5-6040210-8-8. OCLC 1062352461. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1062352461.

- ↑ Kálmán 1989, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Kálmán 1989, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Современный мансийский язык: лексика, фонетика, графика, орфография, морфология, словообразование: монография; page 288 [1]

- ↑ Rombandeeva, E. I.; Ромбандеева, Е. И. (2017). Sovremennyĭ mansiĭskiĭ i︠a︡zyk : leksika, fonetika, grafika, orfografii︠a︡, morfologii︠a︡, slovoobrazovanie. Obsko-ugorskiĭ institut prikladnykh issledovaniĭ i razrabotok, Обско-угорский институт прикладных исследований и разработок. Ti︠u︡menʹ. pp. 128. ISBN 978-5-6040210-8-8. OCLC 1062352461. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1062352461.

- ↑ Rombandeeva, E. I.; Ромбандеева, Е. И. (2017). Sovremennyĭ mansiĭskiĭ i︠a︡zyk : leksika, fonetika, grafika, orfografii︠a︡, morfologii︠a︡, slovoobrazovanie. Obsko-ugorskiĭ institut prikladnykh issledovaniĭ i razrabotok, Обско-угорский институт прикладных исследований и разработок. Ti︠u︡menʹ. pp. 133. ISBN 978-5-6040210-8-8. OCLC 1062352461. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1062352461.

- ↑ Rombandeeva, E. I.; Ромбандеева, Е. И. (2017). Sovremennyĭ mansiĭskiĭ i︠a︡zyk : leksika, fonetika, grafika, orfografii︠a︡, morfologii︠a︡, slovoobrazovanie. Obsko-ugorskiĭ institut prikladnykh issledovaniĭ i razrabotok, Обско-угорский институт прикладных исследований и разработок. Ti︠u︡menʹ. pp. 134. ISBN 978-5-6040210-8-8. OCLC 1062352461. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1062352461.

- ↑ Susanna S. Virtanen; Csilla Horváth; Tamara Merova (2021). Pohjoismansin peruskurssin (5 op). POHJOISMANSIN PERUSKURSSI. Helsinki: Helsingin yliopisto. https://helda.helsinki.fi/bitstream/handle/10138/330329/Virtanen_Horvath_Merova_Pohjoismansin_peruskurssi_17082021.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y.

References

- Nyelvrokonaink. Teleki László Alapítvány, Budapest, 2000.

- A világ nyelvei. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest

- Abondolo, Daniel, ed. The Uralic Languages.

- Kálmán, Béla (1965). Vogul Chrestomathy. Indiana University Publications. Uralic and Altaic Series. 46. The Hague: Mouton.

- Kálmán, Béla (1989) (in hu,de). Chrestomathia Vogulica (3rd ed.). Budapest: Tankönyvkiadó. ISBN 963-18-2088-2.

- Kulonen, Ulla-Maija (2007) (in fi). Itämansin kielioppi ja tekstejä. Apuneuvoja suomalais-ugrilaisten kielten opintoja varten. XV. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. ISBN 978-952-5150-87-2.

- Munkácsi, Bernát and Kálmán, Béla. 1986. Wogulisches Wörterbuch. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest. [In German and Hungarian.]

- Riese, Timothy. Vogul: Languages of the World/Materials 158. Lincom Europa, 2001. ISBN 3-89586-231-2

- Ромбандеева, Евдокия Ивановна. Мансийский (вогульский) язык, Russian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Linguistics, 1973. [In Russian.]

External links

| Mansi language test of Wikipedia at Wikimedia Incubator |

- Mansi at Omniglot

- Digital version of Munkácsi and Kálmán's dictionary

- Mansi language dictionary

- Mansi basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database

- Red Book of the Peoples – Mansi history

- Endangered Languages of Indigenous Peoples of Siberia – Mansi education

- OLAC resources in and about the Mansi language

- Документация и изучение верхнелозьвинского диалекта