Localization theorem

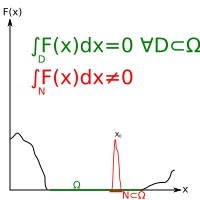

In mathematics, particularly in integral calculus, the localization theorem allows, under certain conditions, to infer the nullity of a function given only information about its continuity and the value of its integral. Let F(x) be a real-valued function defined on some open interval Ω of the real line that is continuous in Ω. Let D be an arbitrary subinterval contained in Ω. The theorem states the following implication:

A simple proof is as follows: if there were a point x0 within Ω for which F(x0) ≠ 0, then the continuity of F would require the existence of a neighborhood of x0 in which the value of F was nonzero, and in particular of the same sign than in x0. Since such a neighborhood N, which can be taken to be arbitrarily small, must however be of a nonzero width on the real line, the integral of F over N would evaluate to a nonzero value. However, since x0 is part of the open set Ω, all neighborhoods of x0 smaller than the distance of x0 to the frontier of Ω are included within it, and so the integral of F over them must evaluate to zero. Having reached the contradiction that ∫NF(x) dx must be both zero and nonzero, the initial hypothesis must be wrong, and thus there is no x0 in Ω for which F(x0) ≠ 0.

The theorem is easily generalized to multivariate functions, replacing intervals with the more general concept of connected open sets, that is, domains, and the original function with some F(x) : Rn→R, with the constraints of continuity and nullity of its integral over any subdomain D⊂Ω. The proof is completely analogous to the single variable case, and concludes with the impossibility of finding a point x0 ∈ Ω such that F(x0) ≠ 0.

Example

An example of the use of this theorem in physics is the law of conservation of mass for fluids, which states that the mass of any fluid volume must not change:

Applying the Reynolds transport theorem, one can change the reference to an arbitrary (non-fluid) control volume Vc. Further assuming that the density function is continuous (i.e. that our fluid is monophasic and thermodynamically metastable) and that Vc is not moving relative to the chosen system of reference, the equation becomes:

As the equation holds for any such control volume, the localization theorem applies, rendering the common partial differential equation for the conservation of mass in monophase fluids:

This article does not cite any external source. HandWiki requires at least one external source. See citing external sources. (2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

|